Introduction

Crossing the Andes, we found ourselves in the digital valleys of Peru, where a new variation of the loan scam awaited us. Much like the schemes in Brazil, these operations played on hope and desperation, luring victims with promises of financial relief. The setup was so convincing that it seemed like help was just within reach – until it vanished, leaving victims exploited and vulnerable.

Since 2024, threat actors have created at least 16 scam domains impersonating one of Peru’s leading banks.

This particular phishing targets individuals through a seemingly legitimate loan application process, designed to harvest valid card credentials and corresponding PIN codes. These credentials are then either sold on the black market or used in further phishing activities.

Key discoveries

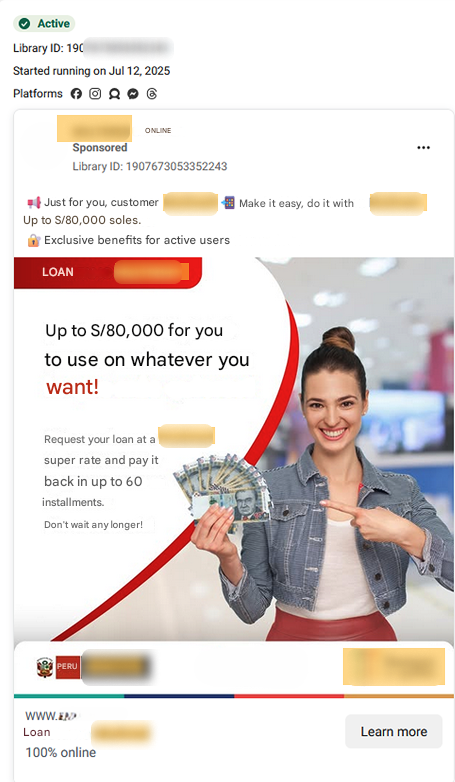

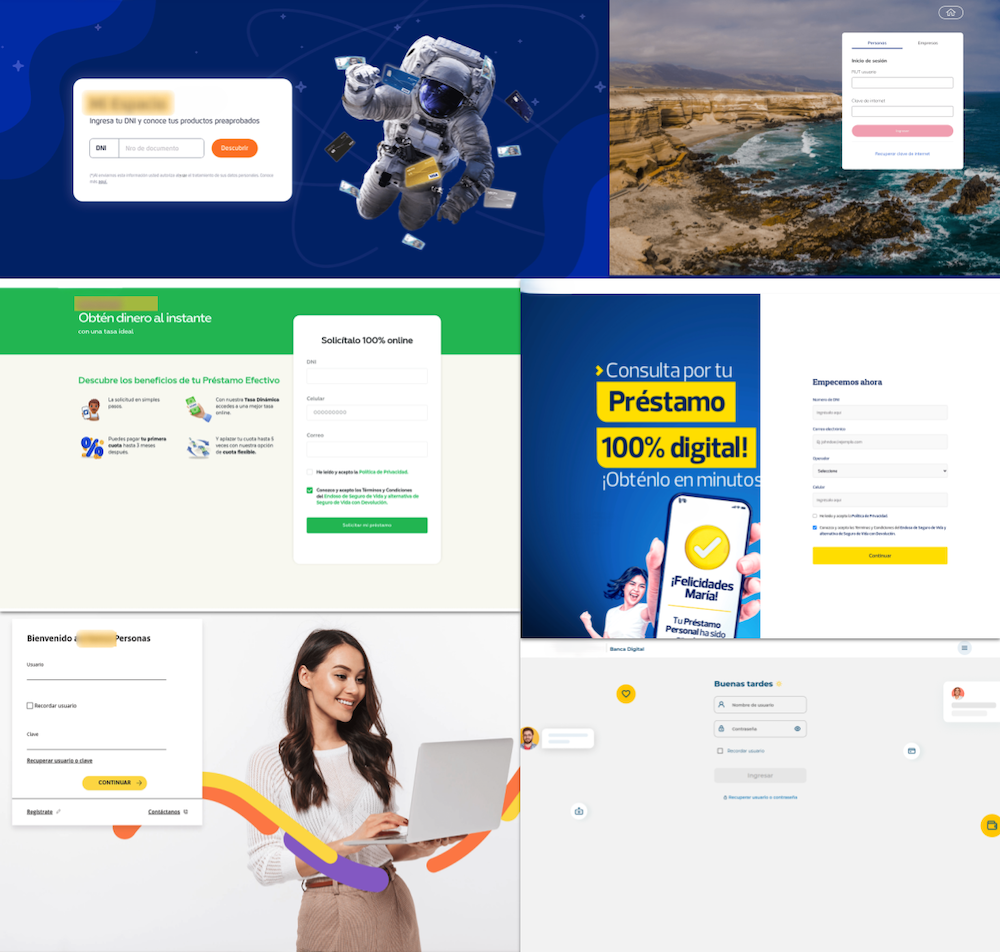

- To spread the scam campaign the cybercriminals utilized distinct social media advertisements.

- The phishing scheme harvests valid card credentials and PIN codes through a seemingly legitimate loan application process.

- They used the Luhn algorithm to check the validity of entered credit card numbers, ensuring scammers only deal with high-quality credentials.

- Approximately 370 unique domains have been identified in this fraud campaign.

- The campaign has expanded its targets to financial institutions in other Latin American countries.

Who may find this blog interesting:

- Financial institutions – Banks and fintechs in Peru and across Latin America who want to understand emerging scam tactics targeting their customers.

- Cybersecurity professionals – Analysts, threat hunters, and fraud prevention teams studying phishing techniques, scam infrastructures, and regional fraud trends.

- Digital risk protection providers – Vendors and MSSPs focused on detecting and mitigating brand abuse and online fraud.

- Regulators and policymakers – Organizations concerned with consumer protection, digital fraud, and financial crime in the LATAM region.

- Researchers and journalists – Those covering cybercrime, fraud schemes, and the evolution of phishing campaigns.

- Informed consumers – Especially in Peru and neighboring countries, to raise awareness of how sophisticated loan scams operate.

Group-IB Threat Intelligence Portal:

Group-IB customers can access our Threat Intelligence portal for more information about the loan fraud scheme described in this blog.

From Ads to Victims: The Path of the Scam

Between 2024 and 2025, our analysis has identified approximately 35 distinct social media advertisements operating as integral components of this scam campaign. These advertisements, strategically disseminated across various platforms, are designed to lure unsuspecting users into fraudulent schemes. The observed patterns suggest a sophisticated and evolving operation, continuously adapting its tactics to maximize reach and effectiveness.

Input, Validate, Exfiltrate

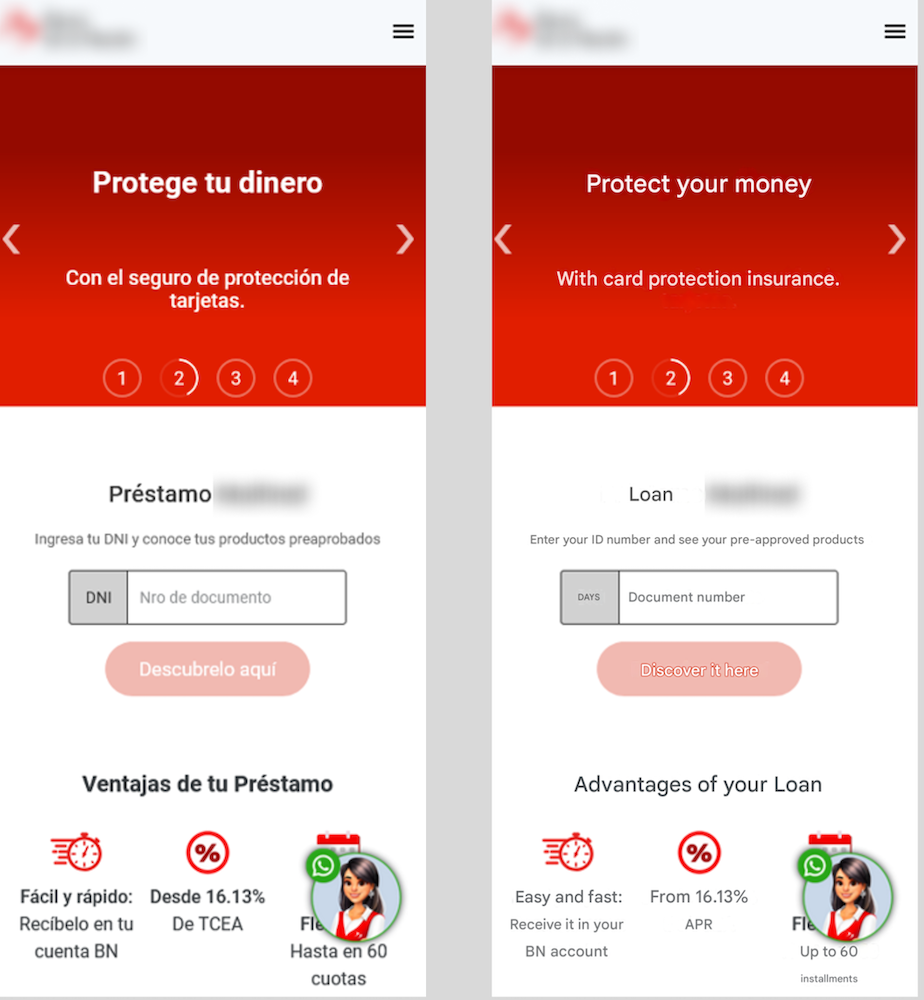

Figure 2: Initial landing page requesting the ID number. English translation provided.

The journey begins innocently enough, with the victim entering their national identification number, such as a DNI (Documento nacional de identidad – National Identity Card). Oddly enough, any input is accepted, creating a false sense of progress and building the victim’s trust.

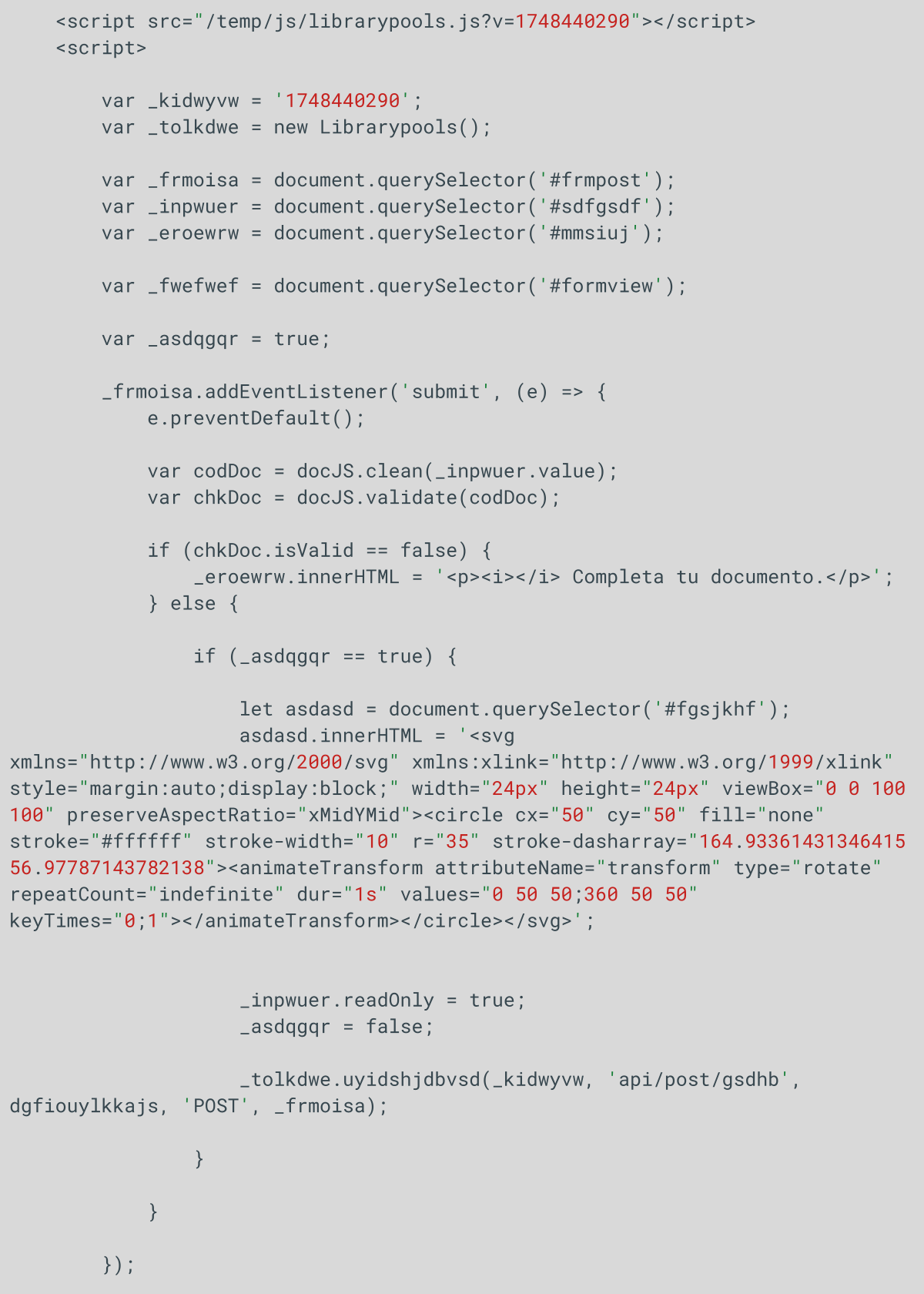

There is a script on this phishing page that is processing data.

The script sends the DNI (identification number) to the server via the API endpoint /api/post/gsdhb. Before sending, the number undergoes the following steps:

- Cleaning (only numeric characters are retained).

- Validation (the length must be exactly 8 characters).

If all checks are passed, a POST request is sent to the server at /api/post/gsdhb along with parameters such as the DNI and the session identifier _kidwyvw.

Figure 3: Snippet of the html code with the variable “_kidwyvw”.

Personalized offers – A trust-building ruse

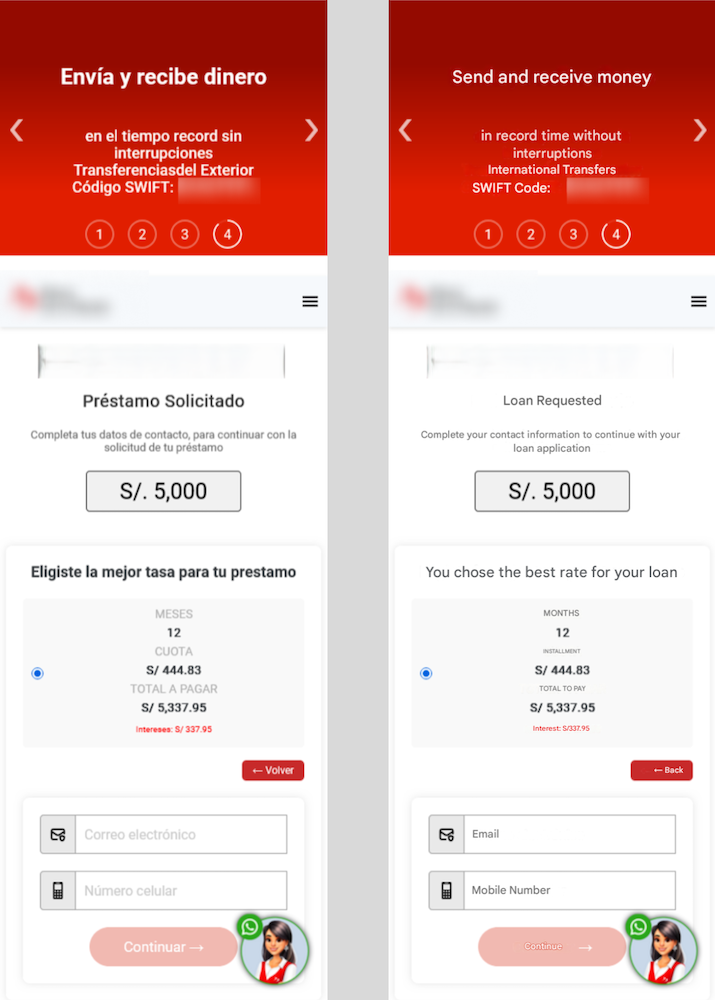

Next, victims are shown a range of loan options with varying amounts and repayment terms, encouraging them to select what feels like a tailored financial solution.

Figure 4: After selecting a loan amount, victims must enter their email and phone number. English translation provided.

The next step involves collecting basic contact details. Victims are asked to provide their email and phone number. While the email field has no strict validation, the phone number must start with a specific digit, adding a subtle layer of authenticity to the phishing.

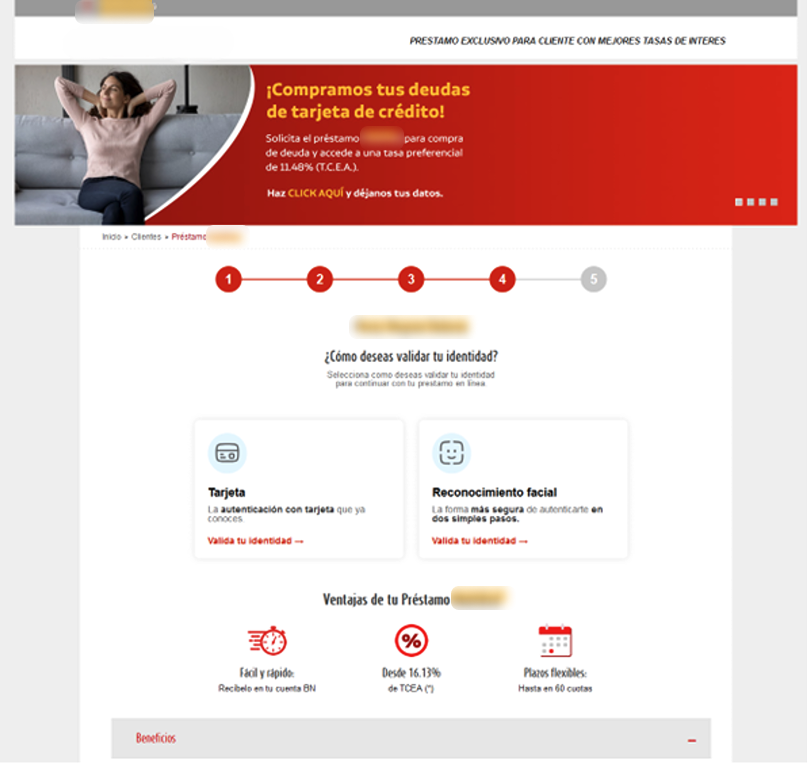

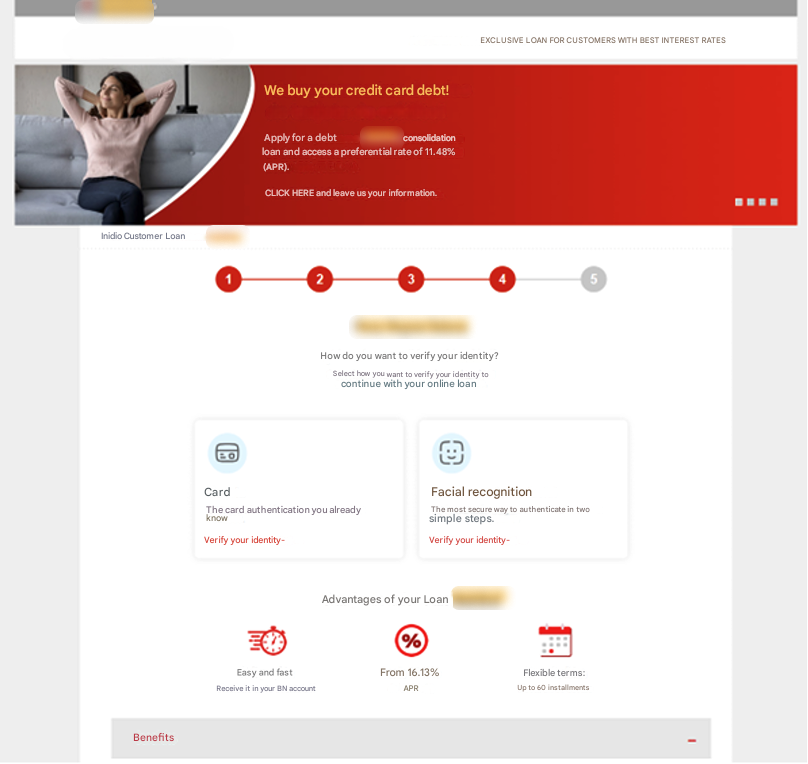

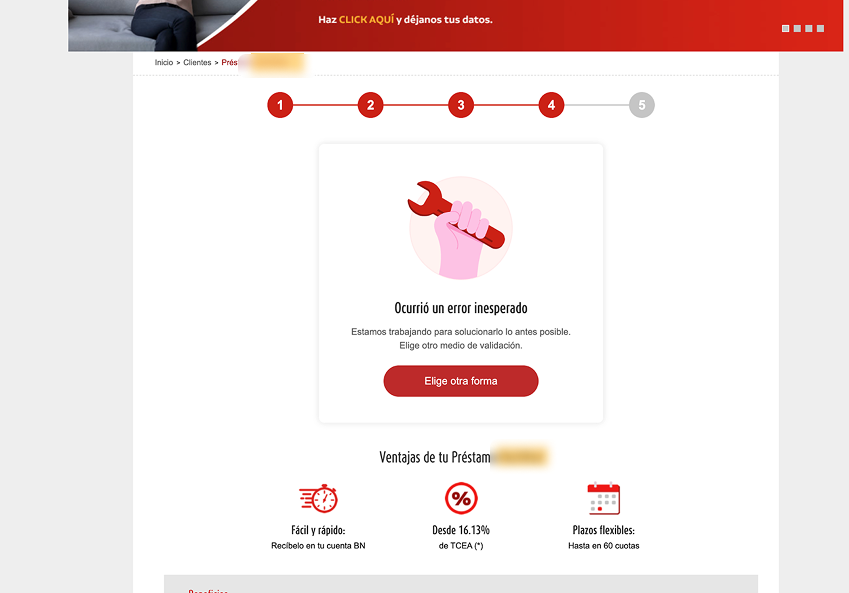

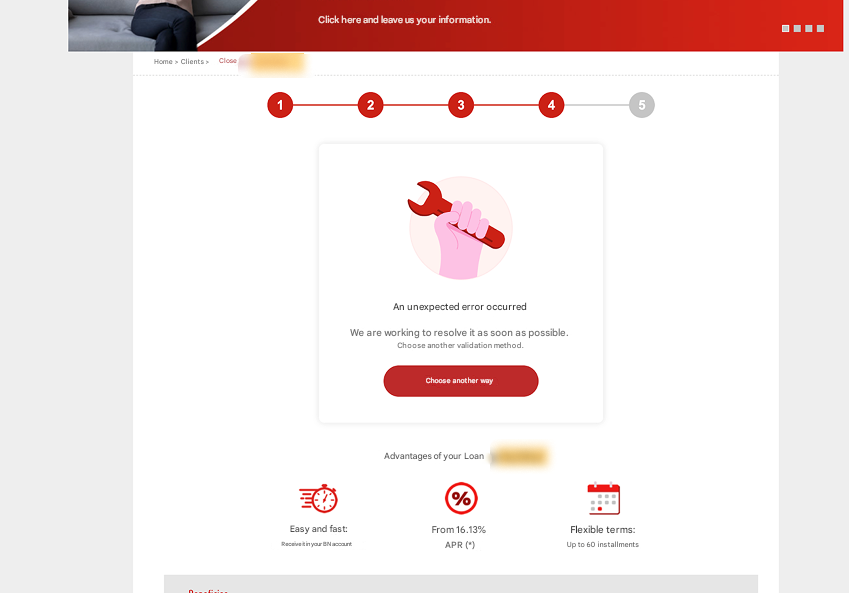

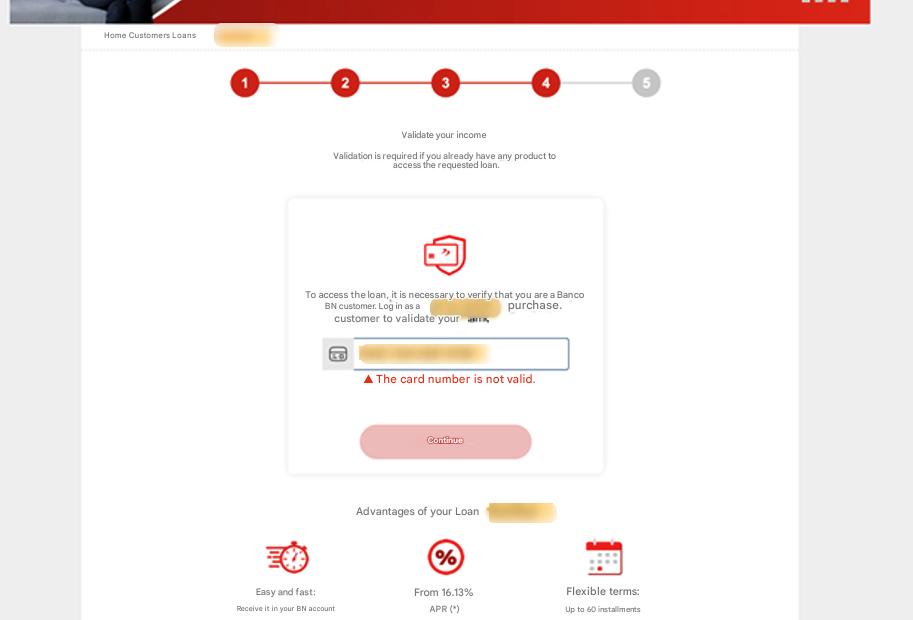

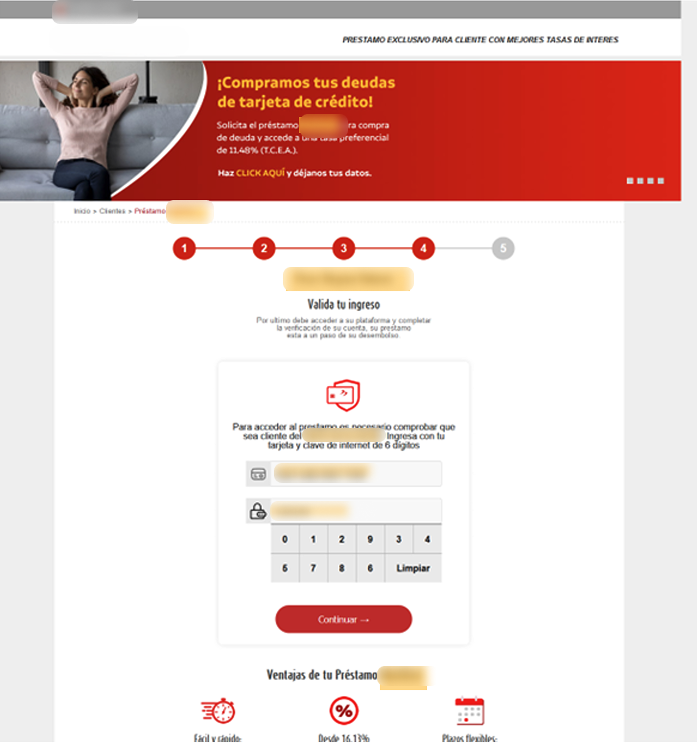

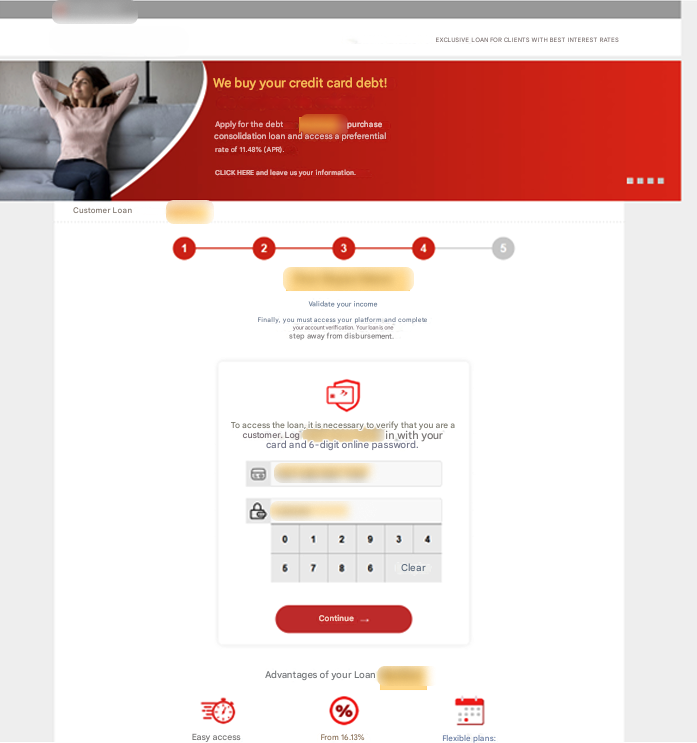

The trap tightens at the verification stage, where two options are presented: facial recognition or inputting bank card details. The facial recognition feature is intentionally broken, always returning an error to nudge the victim toward entering their card information instead.

Here, the phishing gets even more sophisticated. The system checks the entered card details with the Luhn algorithm, a simple checksum formula used to validate various identification numbers. It’s widely used to verify credit card numbers. If the card isn’t recognized, the victim is shown an error message, halting their progress. This ensures the scammers only deal exclusively with genuine, valid cards issued by the specific brand they are targeting.

Once the card is verified, victims are prompted to enter additional sensitive details, such as their online banking password and a 6-digit PIN code. These new details are then linked to the leaked card information, significantly increasing the credentials’ value on the black market.

After completing the process, victims are falsely informed that their loan application is under review and that a bank representative will contact them soon. To cement the phishing’s credibility, victims are redirected to the official bank website, leaving them completely unaware that they’ve just been defrauded.

Beyond Borders: The Scam’s LATAM Footprint

In this particular scam scheme, Group-IB investigators have identified approximately 370 unique domains specifically designed to impersonate financial institutions. While the primary focus of this elaborate operation appears to be on Peru, with a significant concentration of malicious activity directed towards financial entities within the country, the threat is not confined to a single nation.

Further analysis reveals that the scam’s reach extends to other Latin American countries. Brands and financial institutions in nations such as Colombia, El Salvador, Chile, and Ecuador, have also been targeted.

Specifically, the observed impersonation efforts include:

- Perú: Three distinct financial brands have been mimicked within Peru.

- Colombia: One financial brand in Colombia has been targeted.

- El Salvador: One financial brand in El Salvador has been targeted.

- Chile: One financial brand in Chile has been targeted.

- Ecuador: One financial brand in Ecuador has been targeted.

This indicates a broader, regional strategy employed by the perpetrators, aiming to exploit vulnerabilities across multiple markets within the LATAM region. The discovery of such a high number of unique domains demonstrate the scale and sophistication of this particular fraudulent operation.

Figure 9: Group-IB research indicates the fraud campaign has expanded throughout LATAM.

Behind the Curtain: Technical Insights into the JavaScript Payload

A deeper look into the phishing infrastructure reveals a JavaScript file named librarypools.js, served from the /temp/js/ directory. This script plays a central role in data collection and exfiltration and contains multiple red flags indicating malicious intent:

- Obfuscated Function Names: The class Librarypools is composed of functions with randomized or meaningless names like uyidshjdbvsd, fghdgnfdddv, and sdfgsdfgsf. This deliberate obfuscation complicates analysis and is a hallmark of phishing kits.

- Comprehensive Form Data Harvesting: The script’s serialize() function scrapes user input across all standard form fields – including names, passwords, emails, and payment credentials – and prepares them for exfiltration via dynamically built fetch or XMLHttpRequest calls. The submission routes are constructed using session-specific path segments, making detection by static filters more difficult.

- Card Number Validation via Luhn Algorithm: A function named sdfgsdfgsf() implements the Luhn check to verify whether a submitted card number is potentially valid. This reduces noise for the scammers and filters out mistyped or fake data.

- Custom Route Mapping and Thematic Consistency: The method gegsdfgsh() maps numeric inputs to Spanish-language phishing themes, such as ‘mi-prestamo-nacion’, ‘dineroalinstante’, and ‘reconocimiento-facial’. These endpoints reinforce the illusion of legitimacy and suggest a modular backend capable of simulating multiple loan brands or services.

- Conditional Validation Logic: Input validators ensure that fields like phone numbers and email addresses conform to expected patterns. This both reinforces victim trust and improves the quality of harvested data.

The strategic placement of this script in a temporary subdirectory (/temp/js/) and its modular architecture indicate a scalable infrastructure designed to support multiple campaigns with minimal reconfiguration.

Conclusion

Phishing operations in Peru, particularly those tied to fake loan offerings, demonstrate increasing technical maturity. By combining effective social engineering with dynamic scripting, database checks, and obfuscated code, scammers are able to maximize the credibility of their campaigns while harvesting only high-quality credentials.

This convergence of psychological manipulation and technical precision underscores the importance of threat intelligence in understanding regional scam tactics and developing meaningful countermeasures.

Recommendations

For financial institutions:

- Invest in proactive customer education to help users recognize the red flags of fraudulent loan offers.

- Strengthen digital risk monitoring through services such as Group-IB’s Digital Risk Protection platform, which can help you act quickly to dismantle phishing domains impersonating your brand.

- Use layered defenses such as multi-factor authentication and transaction alerts to protect clients even if credentials are compromised.

- Share intelligence and best practices with peers and regulators to stay ahead of emerging fraud patterns.

For consumers:

- Remember: if a loan offer looks too good to be true, it probably is.

- Access financial services only through official bank channels – websites, apps, or verified customer service numbers.

- Always double-check the URL before entering personal or banking data.

- Never share sensitive details like your DNI, PIN, or online banking credentials unless you are absolutely sure you’re on a legitimate platform.

For regulators and policymakers:

- Foster regional collaboration in Latin America to respond more effectively to cross-border fraud campaigns.

- Support awareness initiatives that empower citizens to spot and avoid scams.

- Work with digital platforms to hold advertisers accountable, ensuring that fraudulent campaigns are swiftly taken down.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What are loan scams?

Loan scams often involve the use of fake promotional ads impersonating legitimate financial institutions such as banks. Victims are lured with attractive interest rates on new loans or exclusive offers to buy out existing loans with very flexible repayment plans.

How does the scam affect victims?

The purpose is to harvest personal financial information such as credit card details and pin numbers, which are then sold on the black market or used in other fraud campaigns.

Why do social engineering scams work?

Scammers often create a fake sense of urgency such as having time-limited or limited availability offers that pressure victims to act immediately. Combined with authentic-looking websites of trusted local institutions, victims are lulled into a sense of familiarity, lowering their guard enough to bypass normal due diligence and scrutiny.

What are the techniques used by loan scammers?

- The scam campaign observed in Peru and LATAM employs social engineering via targeted phishing ads on social media.

- Group-IB researchers have identified approximately 370 unique domains designed to impersonate financial institutions.

- Use of advanced scripts and algorithms to check quality of data before harvesting, increasing its value in the black market.

- Redirection back to official websites to mask scam activity and delay detection by victims.

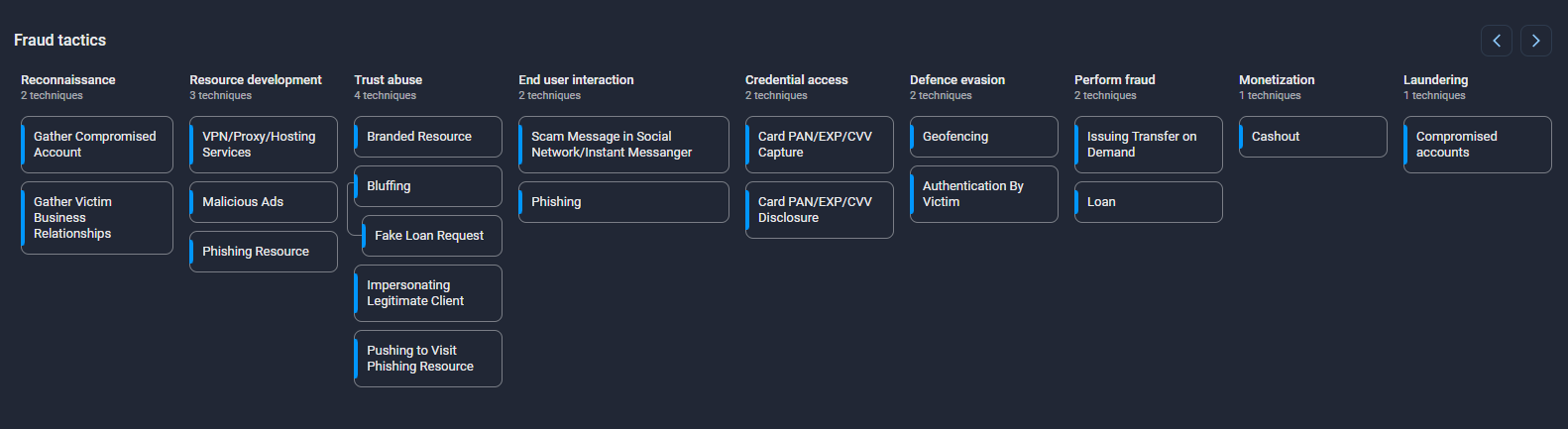

Group-IB Fraud Matrix

DISCLAIMER: All technical information, including malware analysis, indicators of compromise and infrastructure details provided in this publication, is shared solely for defensive cybersecurity and research purposes. Group-IB does not endorse or permit any unauthorized or offensive use of the information contained herein. The data and conclusions represent Group-IB’s analytical assessment based on available evidence and are intended to help organizations detect, prevent, and respond to cyber threats.

Group-IB expressly disclaims liability for any misuse of the information provided. Organizations and readers are encouraged to apply this intelligence responsibly and in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.

This blog may reference legitimate third-party services such as social media platforms and others, solely to illustrate cases where threat actors have abused or misused these platforms.