Introduction

In October 2025, Group-IB specialists detected a new wave of malware attacks targeting users in Uzbekistan. This research provides an in-depth overview of the findings: how the malware is evolving, which distribution schemes are being used by threat actors, and how they are adapting to modern Android protection mechanisms.

A key shift in attacker tactics is the transition from direct delivery of trojans to a more stealthy distribution model. Previously, users received “pure” trojan APKs that acted as malware immediately upon installation. Now, adversaries increasingly deploy droppers disguised as legitimate applications. The dropper looks harmless on the surface but contains a built-in malicious payload, which is deployed locally after installation – even without an active internet connection. In other words, instead of searching for the trojan itself, it is important to focus on dropper artifacts capable of installing the trojan silently on the device. This report outlines the architecture of this scheme, its delivery vectors, and updated threat actors’ internal mechanisms.

This evolution significantly increases the resilience of malicious campaigns against traditional protection methods. Adaptive environment checks – such as emulator detection, installed app scanning, geolocation validation, or debug flag inspection – combined with encrypted payload storage in the assets folder and custom unpacking routines make both static and dynamic analysis more complex.

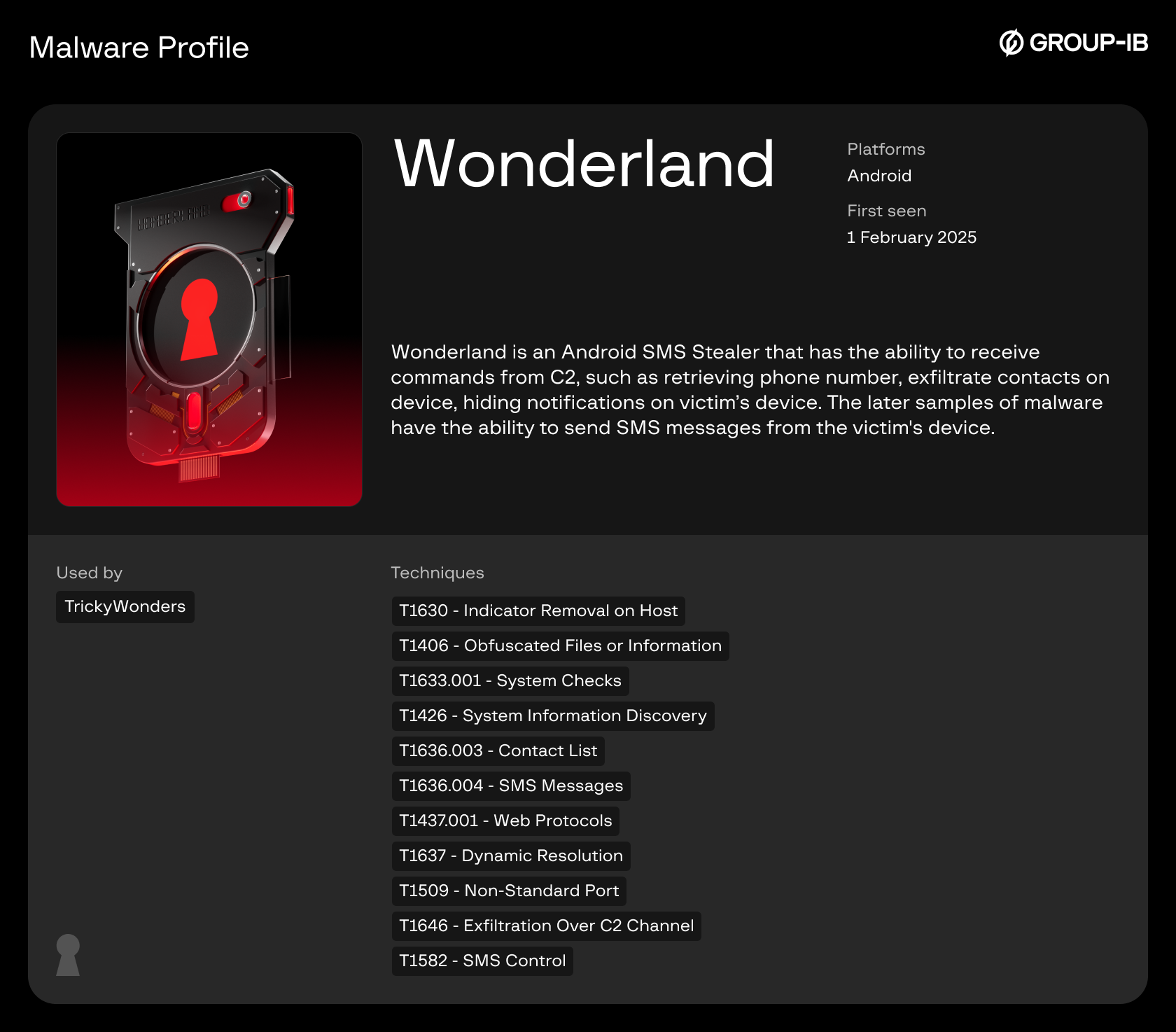

This report describes one of the tracking threat actor groups alongside used tools including droppers and Wonderland, a previously uncovered Android SMS stealer to highlight a new step in the regional malware landscape. Wonderland introduces a bidirectional command-and-control (C2) communication for real-time command execution, allowing for arbitrary USSD requests and SMS sending. Special thanks to Martijn van den Berk for contributing to technical analysis.

Group-IB analysts also take a closer look at the local context: why users in Uzbekistan have become the primary target, what social engineering tactics are used to lure victims, and which types of applications are commonly impersonated by droppers. The following sections of the report will break down the technical details of the observed samples, attack flow, and actionable defense strategies.

Key discoveries

- Two types of droppers most commonly used in campaigns.

- Telegram remains as a key distribution vector for Android SMS stealers in Uzbekistan.

- Cybercriminals adapt to defense mechanisms by utilizing droppers and changing network infrastructure.

- A new malware family, dubbed “Wonderland” has been discovered, the first mass-spreading Android SMS stealer in Uzbekistan with two-way command-and-control (C2) communication.

Who may find this blog interesting:

- Cybersecurity analysts

- Fraud analysts

- Malware researchers and reverse engineers

- Threat intelligence analysts and specialists

- Law enforcement investigators

Group-IB Threat Intelligence Portal: TrickyWonders

Group-IB customers can access our Threat Intelligence portal for more information about the threat actors and malware described in this report:

Threat Actors:

Malware:

Threat Actor Profile

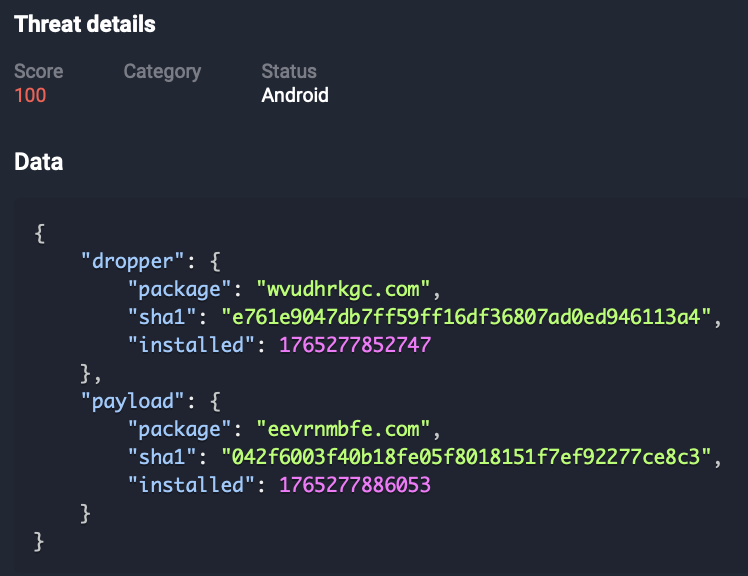

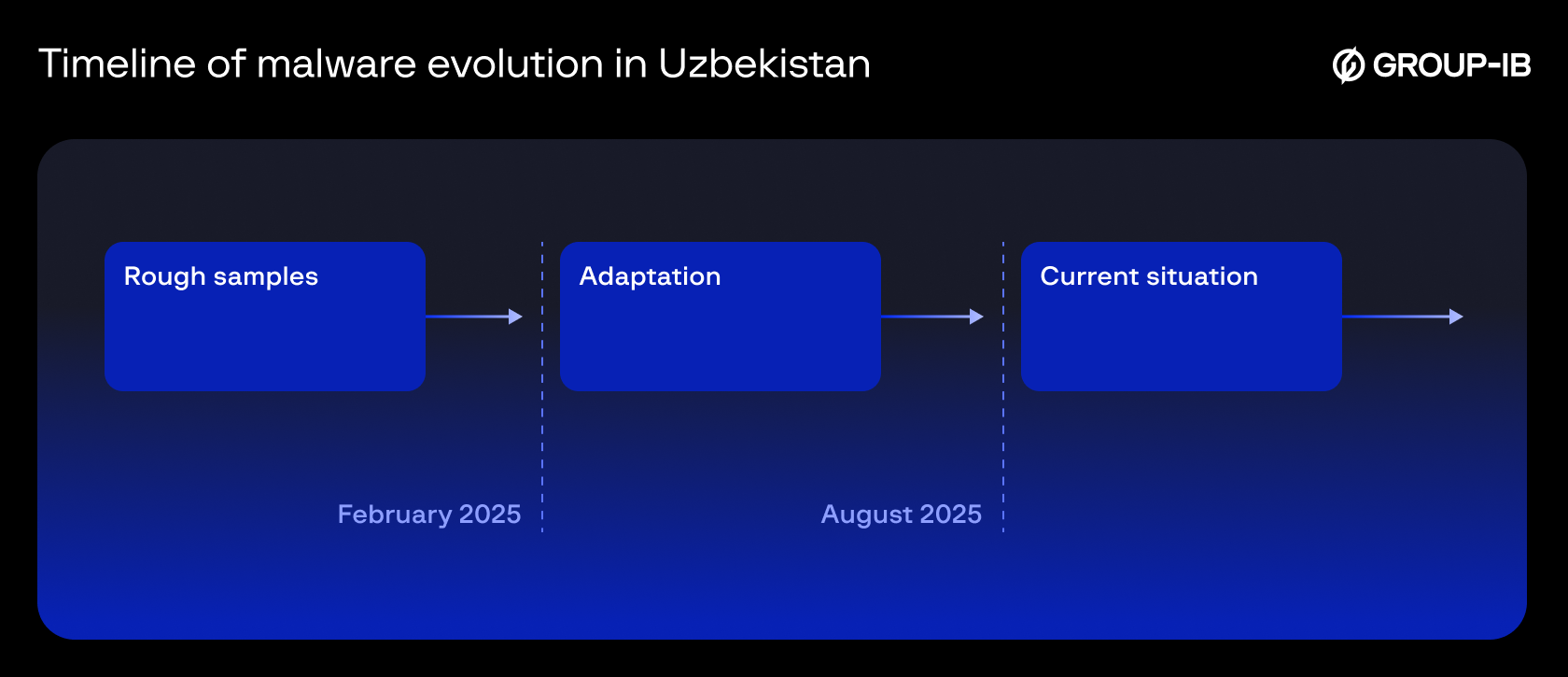

Evolution of Mobile Malware in Uzbekistan

Over the past few years, Group-IB analysts have discovered a clear trend in the development of tools in the hands of cybercriminals, especially Android SMS stealers malware, which has become the most widespread threat in the region. The development of malware in the region can be divided into three major stages, as shown in the graph below.

Figure 1. Timeline of Android malware evolution in Uzbekistan

Round One: Warm Up

Early in the campaign, one of the most prominent threats was the Ajina family of malware. At that time, cybercriminals were just beginning to experiment with the mobile ecosystem, and their tools reflected this immaturity. Most early samples were very consistent, simplified, and designed primarily for mass distribution rather than stealth or sophistication.

The distribution methods were equally primitive: attackers relied on large-scale spam campaigns in Telegram groups and channels, as well as on various social networks. Their goal was to reach as many potential victims as possible with minimal effort, without any targeted delivery or sophisticated social engineering.

From a technical standpoint, the malware itself was very simple in its implementation. The code was almost completely transparent – there were no tricks, packaging, or attempts to hide functionality. Critical operational information, including C2 server addresses, operator IDs, and API endpoints, was hardcoded directly into the application.

Round Two: Adaptation

The next stage in the evolution of malware was a clear strategic shift towards adapting delivery tools and mechanisms to regional conditions. This transformation was most noticeable in the infection vectors used to attract victims. In the early stages, malicious applications were usually disguised as banking or payment services – an approach that, while somewhat effective, often aroused suspicion, especially when such applications were distributed via mass mailings in messengers.

However, in the new phase, fraudsters began to take a more subtle and socially oriented approach. Instead of imitating financial applications, they began to disguise malicious programs as seemingly harmless media files, such as photos and videos. They added attention-grabbing captions designed to arouse curiosity or emotional response, which significantly increased the likelihood of user interaction. This shift marked a transition from direct imitation to more manipulative and context-dependent social engineering.

The technical changes made to the malware samples themselves were no less noticeable. Code that had previously been transparent and easy to check became highly obfuscated, which significantly complicated static analysis. In addition, fraudsters began to regularly change package names. This constant rotation of identifiers allowed the malware to bypass basic signature-based detection mechanisms.

Overall, this period reflects a deliberate and accelerated refinement of both social engineering strategies and the technical sophistication of the campaign, indicating that those behind it began to invest more heavily in stealth, persistence, and evasion.

Round three: Current situation

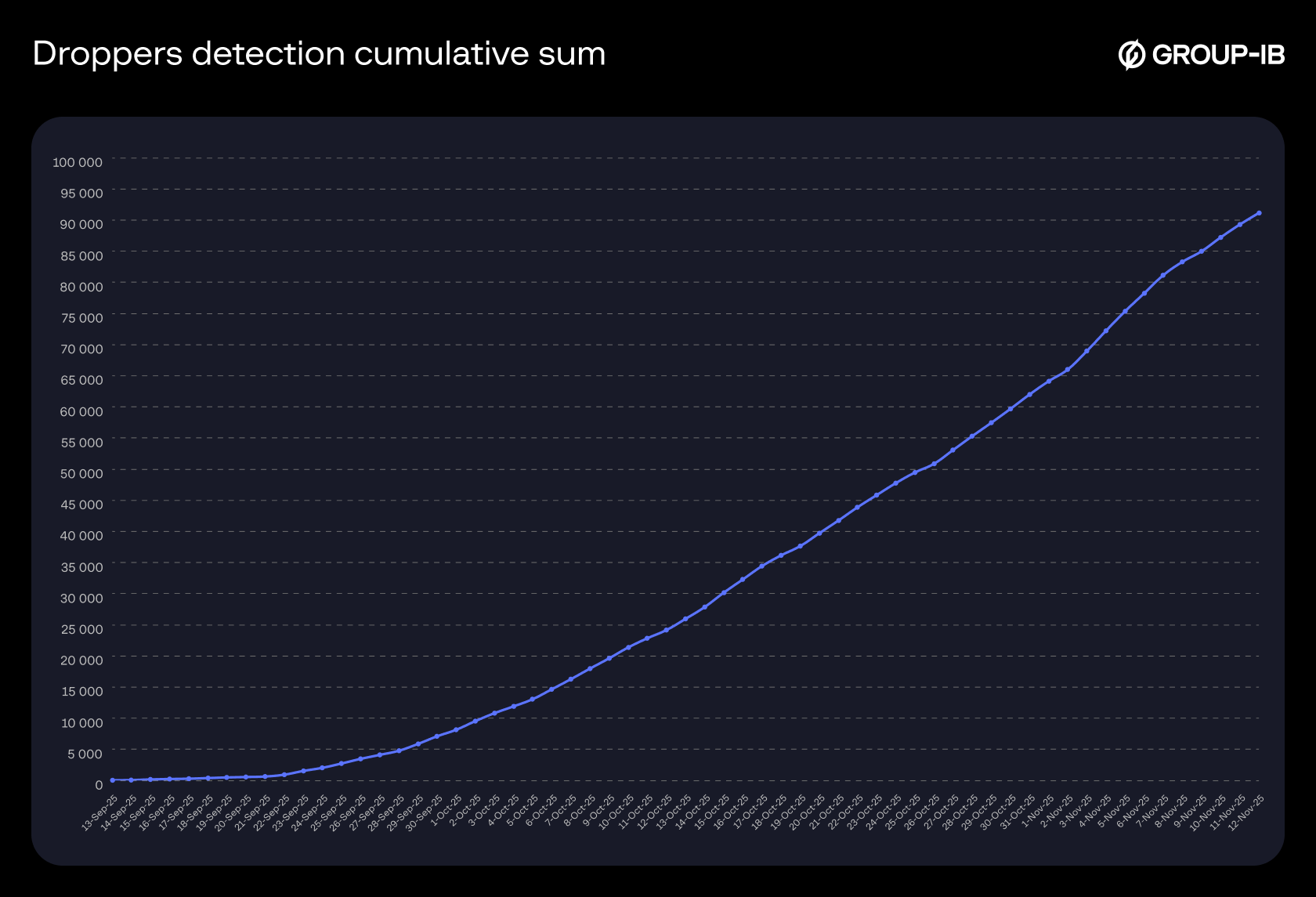

Group-IB analysts observed a significant increase in the number of device infections caused by a new wave of malware. This escalation is closely linked to significant improvements in both the distribution methods and concealment strategies used by attackers.

A key change is the introduction of a multi-stage infection chain. Instead of directly distributing the SMS-stealing program, the fraudsters now deliver a dropper application that has a component for stealing SMS messages built into it as an internal payload. As a result, the original application appears harmless and typically passes standard security checks without raising suspicion. This shift to “clean” first-stage loaders significantly increases the likelihood of successful infection and makes early detection more difficult.

The technical complexity of the malware has also increased. Both dropper and SMS stealer components are now heavily obfuscated, making them much more resistant to reverse engineering. The code has been deliberately made confusing, requiring a disproportionate amount of time and effort to analyze. The situation is further complicated by an automated build pipeline that generates new samples with unique IoCs. This degree of polymorphism renders signature-based detection virtually ineffective and reduces the practical value of deep analysis of each individual build.

In addition, malware has powerful anti-analysis capabilities. It can accurately determine the execution environment and detect signs of virtualization or emulation. When launched in emulators or sandboxes, malware suppresses key functions, preventing researchers from fully studying its behavior and making it difficult to create reliable detection models.

The supporting infrastructure has also become more dynamic and resilient. Operators rely on rapidly changing domains, each of which is used only for a limited set of builds before being replaced. This approach complicates monitoring, disrupts blacklist-based defenses, and increases the longevity of command and control channels.

Taken together, these changes represent a significant leap in the operational maturity of the campaign, which is characterized by multi-layered infection chains, resistance to anti-analysis, and a highly maneuverable infrastructure designed to bypass both technical defenses and professional monitoring.

Dropper software

A dropper is a software component designed to covertly deliver the main malicious payload. Its key task is to ensure the unnoticed introduction of subsequent modules, such as an SMS stealer or other components, while avoiding early detection by security systems.

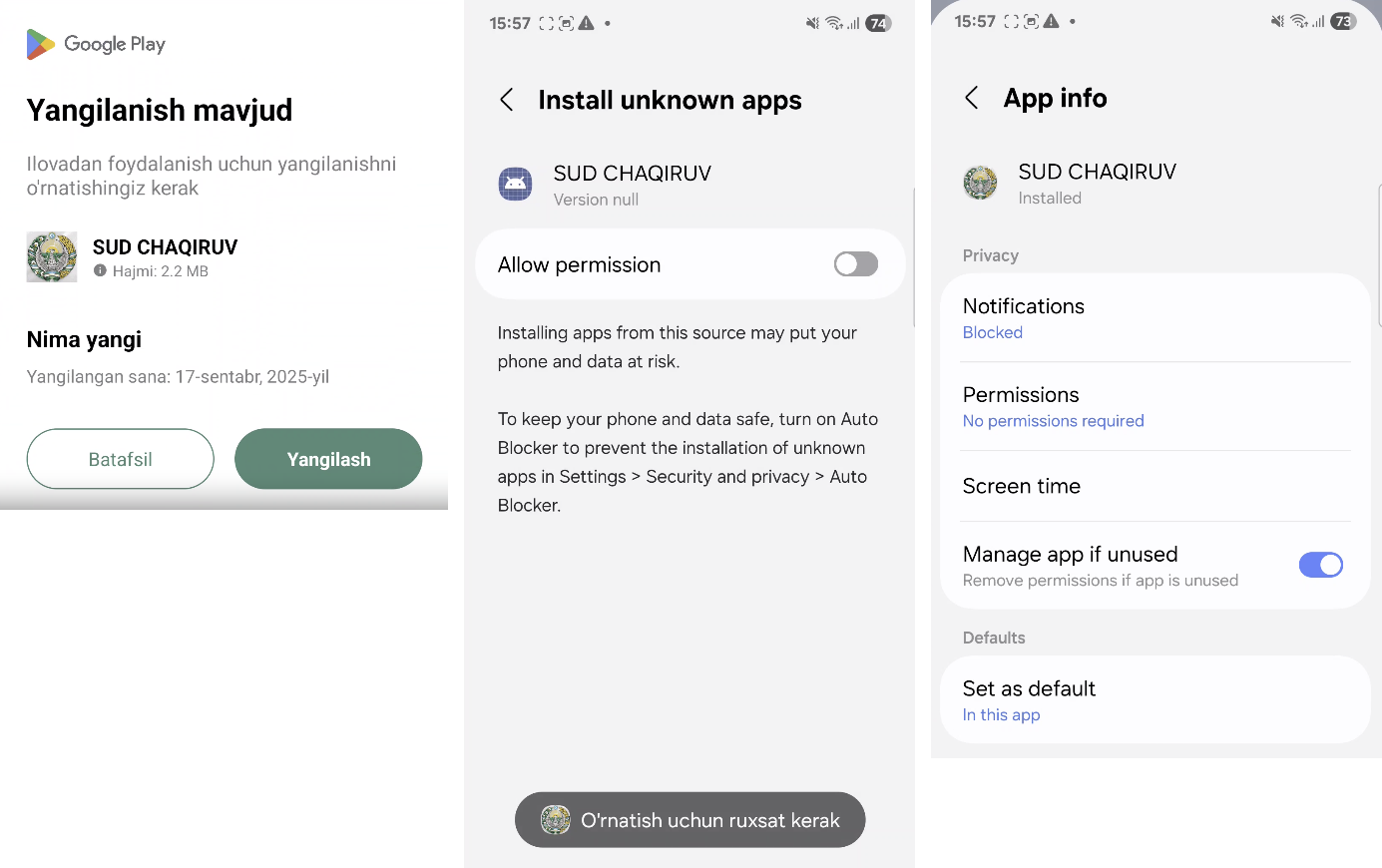

During installation, the dropper behaves as innocently as possible: it does not request sensitive or suspicious permissions, which reduces the likelihood that the user or security system will suspect malicious activity. After launch, the application displays a simple “Update” button to the user, creating the appearance of a standard, safe system process. At this stage, no malicious behavior is apparent, allowing it to successfully pass most basic checks and increase the likelihood of reaching the next stage of infection.

Figure 2. A series of screenshots of a dropper malware masquerading as an app on Google Play.

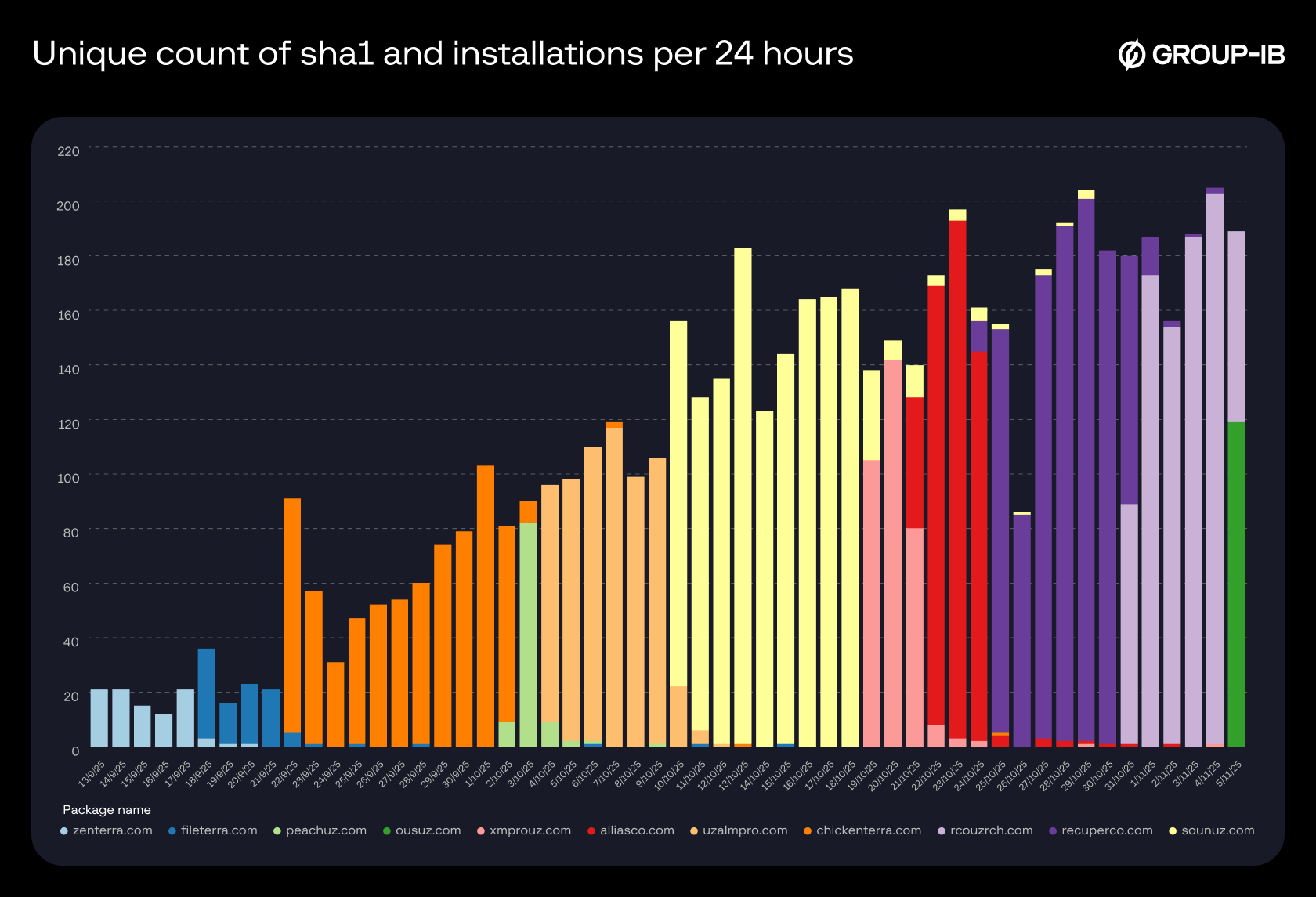

Threat actors frequently change the package names of their malicious applications. In some cases even on a daily basis making name-based detection largely ineffective. This constant renaming acts as a simple but powerful evasion tactic: by regularly rotating identifiers, attackers avoid leaving behind stable markers that security systems could reliably track or recognize.

Figure 3. Charting the timeline of the Droppers.

Figure 4. Droppers detection cumulative sum.

Masquerading as legitimate apps

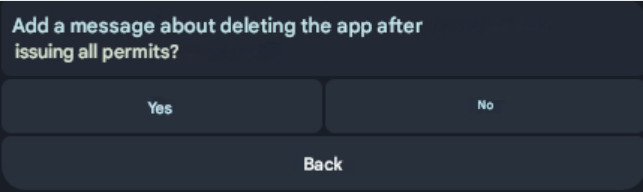

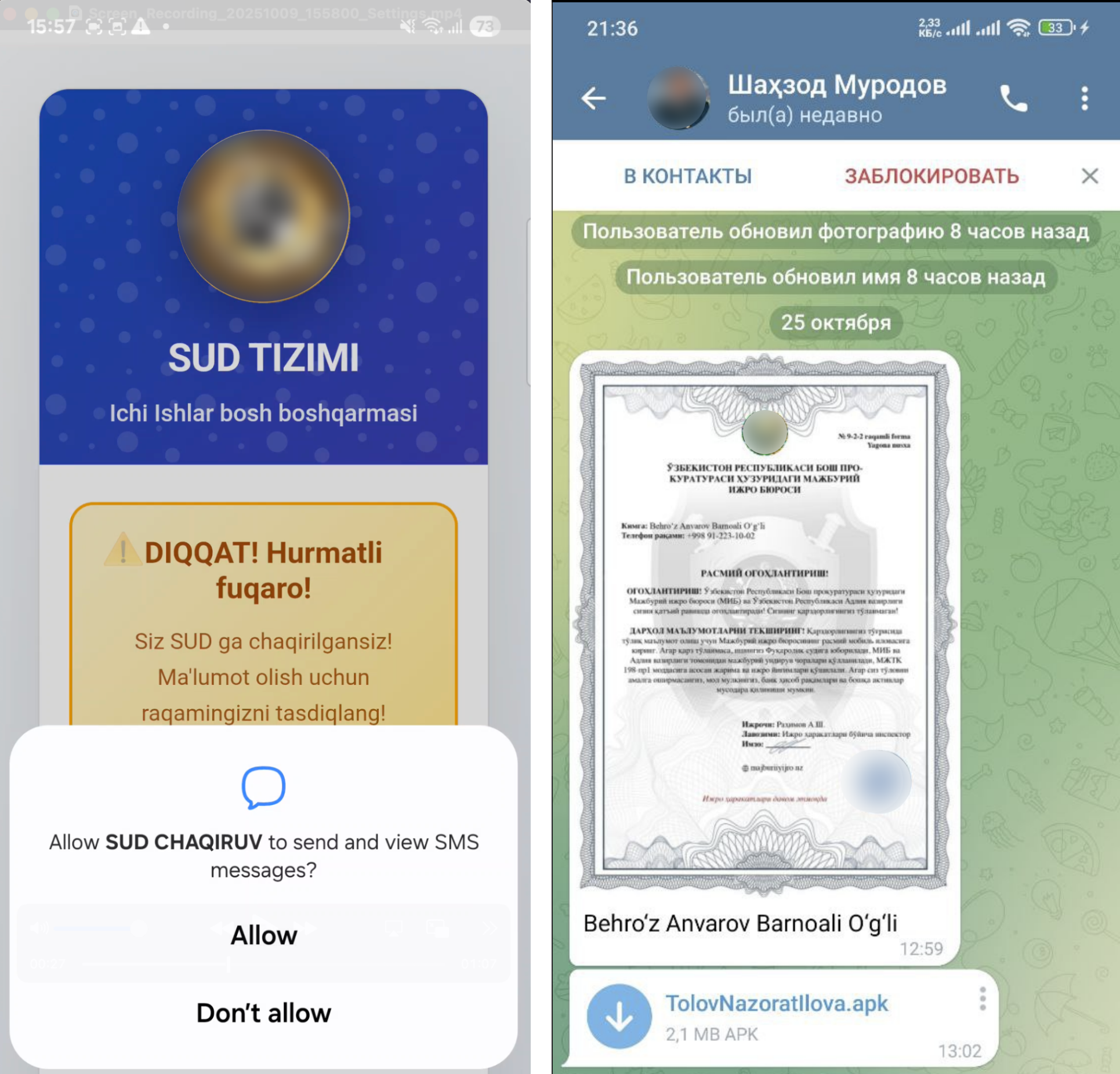

SMS‑stealers pose a greater threat than phishing because of their persistence in the victim’s device. Once the malware is installed, it can repeatedly withdraw funds from the victim’s cards until the attacker loses access to the device. The malware is capable of masquerading as legitimate applications, such as Google Play or appearing as a custom app that launches a pre‑set website immediately. After receiving necessary permissions, it can also display a deceptive “uninstall” prompt that tricks users into thinking the app is being removed.

Figure 5. Capability to add the “uninstall” prompt in APK generation.

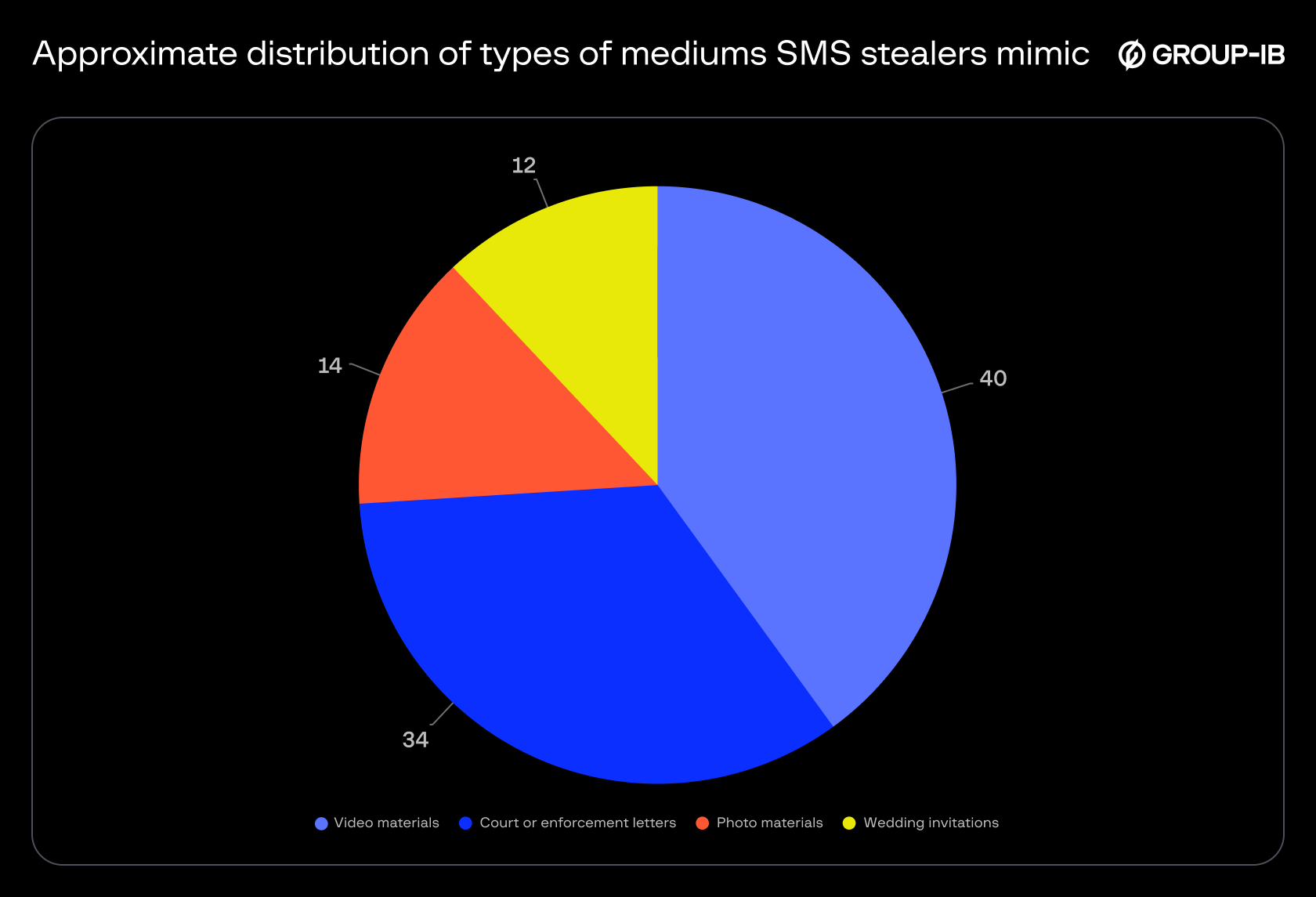

As noted earlier, malware disguises itself as files of other formats, such as videos, photos, and documents. This tactic uses a double extension method, where fraudsters add a fictitious extension to the application name.

Figure 6. Types of mediums that SMS stealers typically mimic.

Figure 7. Screenshots of letters or messages that impersonate official court documents or summons.

Cybercriminal group structure

Cybercriminal groups that distribute Android stealers are organized with their own hierarchy. The groups operate in Telegram and typically contain an owner (campaign initiator, topic starter), developers, vbivers – those who work with stolen cards validation, and workers. Although the owner and vbivers can also distribute the malware, the bulk of the dissemination is carried out by workers who spread the malware in exchange for a share of the stolen funds.

Changes in network infrastructure

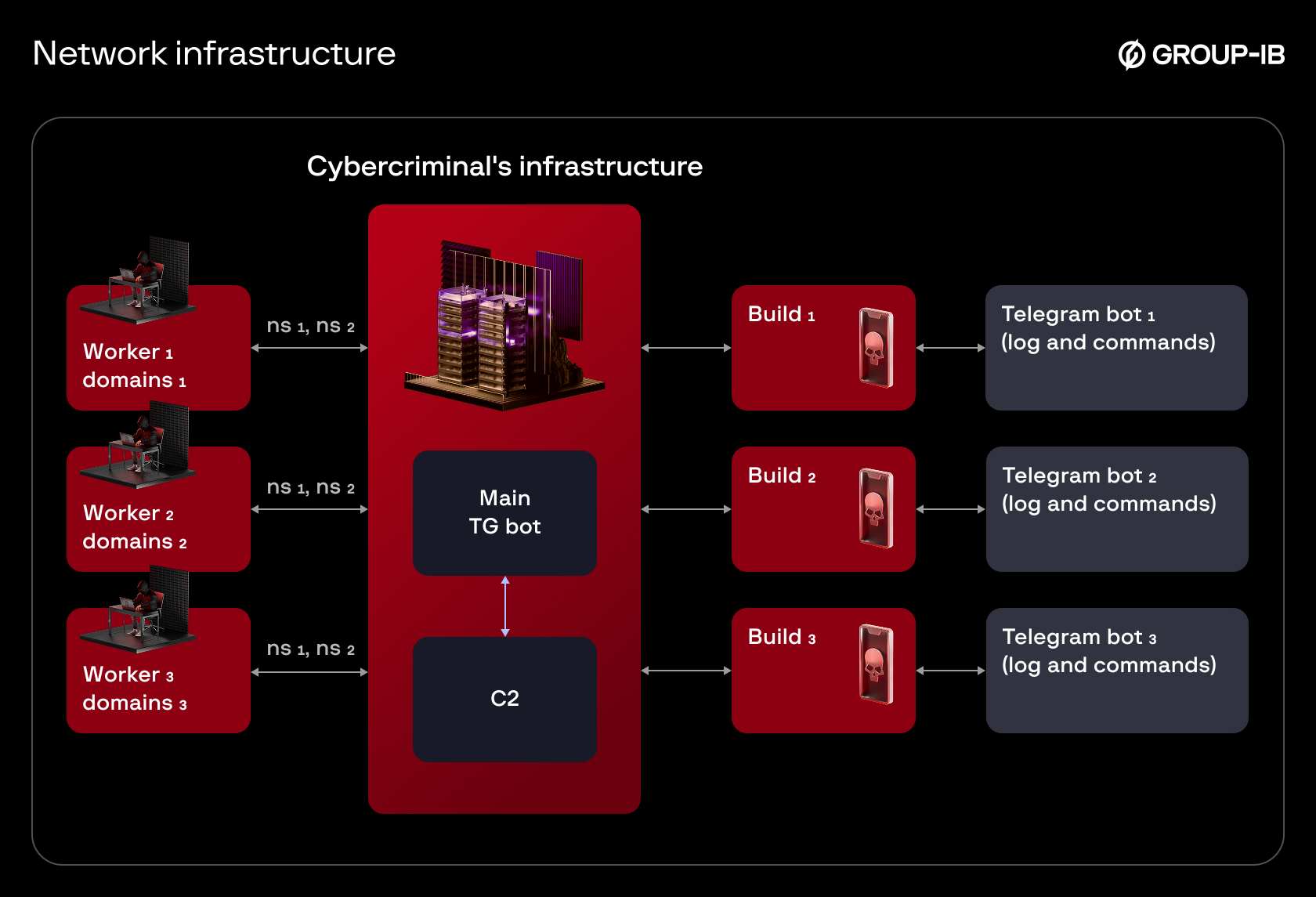

The malicious APKs that are called the “builds” can be provided by group owners or generated via a dedicated Telegram bot. In recent versions, the bot requires workers to list domains they own.

The process for linking domains to the main C2 server:

- Workers add their own domains to the Telegram bot.

- Telegram bot responds with a list of nameservers.

- Workers add these nameservers to their domains’ configuration.

- After DNS propagation domains resolve to the primary C2 server.

Figure 8. Updated network infrastructure.

Without this configuration, the build will not work. This distributed C2 approach gives the attackers a higher degree of independence: a domain takedown will only defunct a limited set of builds, whereas the other builds and the main C2 remain functional.

Methods of distribution

During the research of one of the groups that operates in the Central Asia region, primarily in Uzbekistan, Group-IB analysts revealed the most commonly used tactics for bypassing security, as well as the social engineering methods most frequently used in the region. The malicious files are being distributed using fake Google Play web pages, advertisement campaigns on social networks, fake accounts on dating sites. Cybercriminals utilize social engineering tactics to lure users into installing the APK and granting the required permissions.

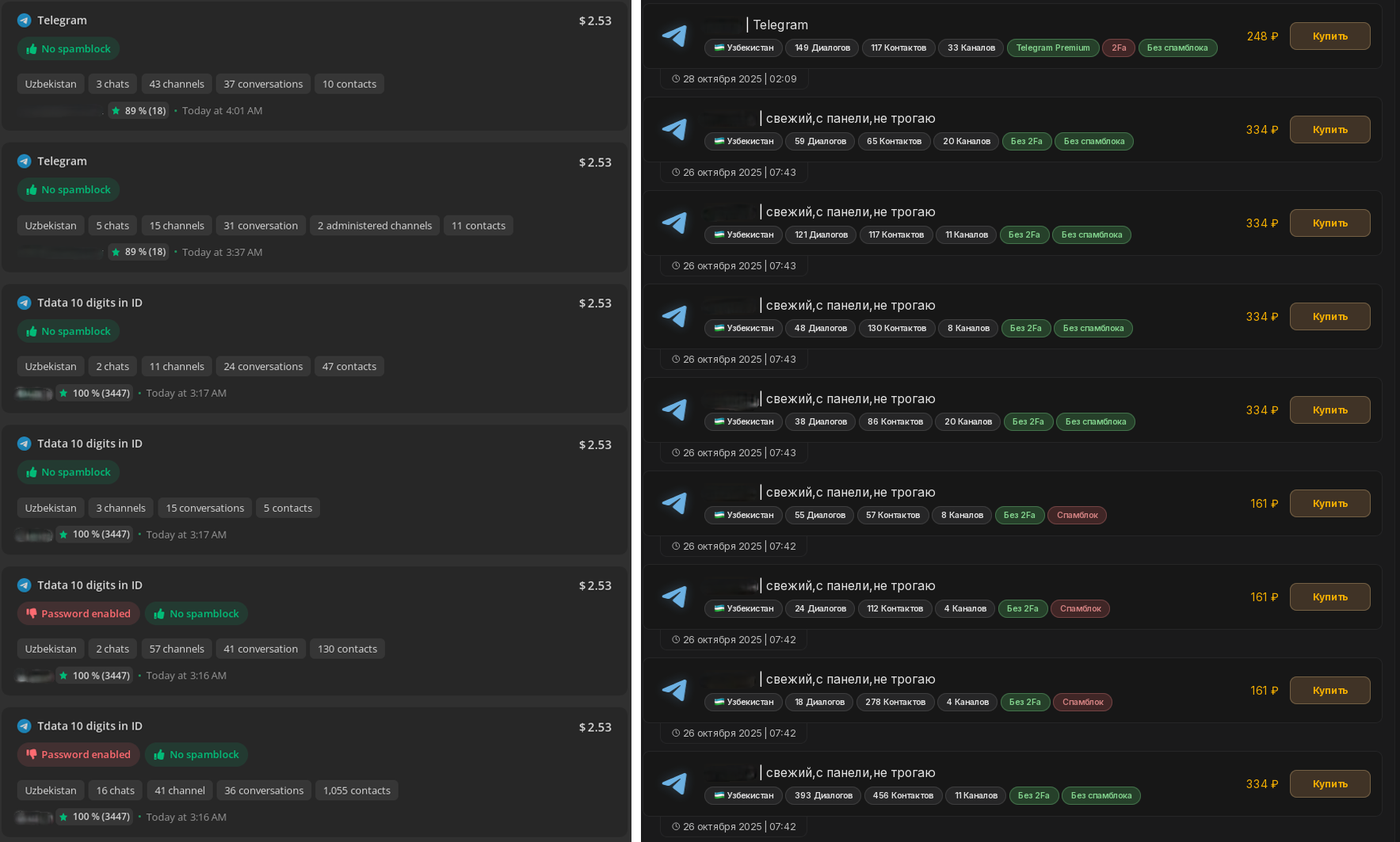

One of the primary infection chains has been identified in Telegram, the dominant instant messaging platform in Uzbekistan. The research shows that the threat actors utilize stolen telegram sessions of Uzbek users sold on darkweb markets to spread the malware.

Figure 9. Screenshots of the sale of stolen Telegram sessions.

Generally, the Telegram has anti-spam detections on the user sending repetitive messages by terminating active sessions and deleting recently sent messages. Cybercriminals utilize various tactics to avoid detection.

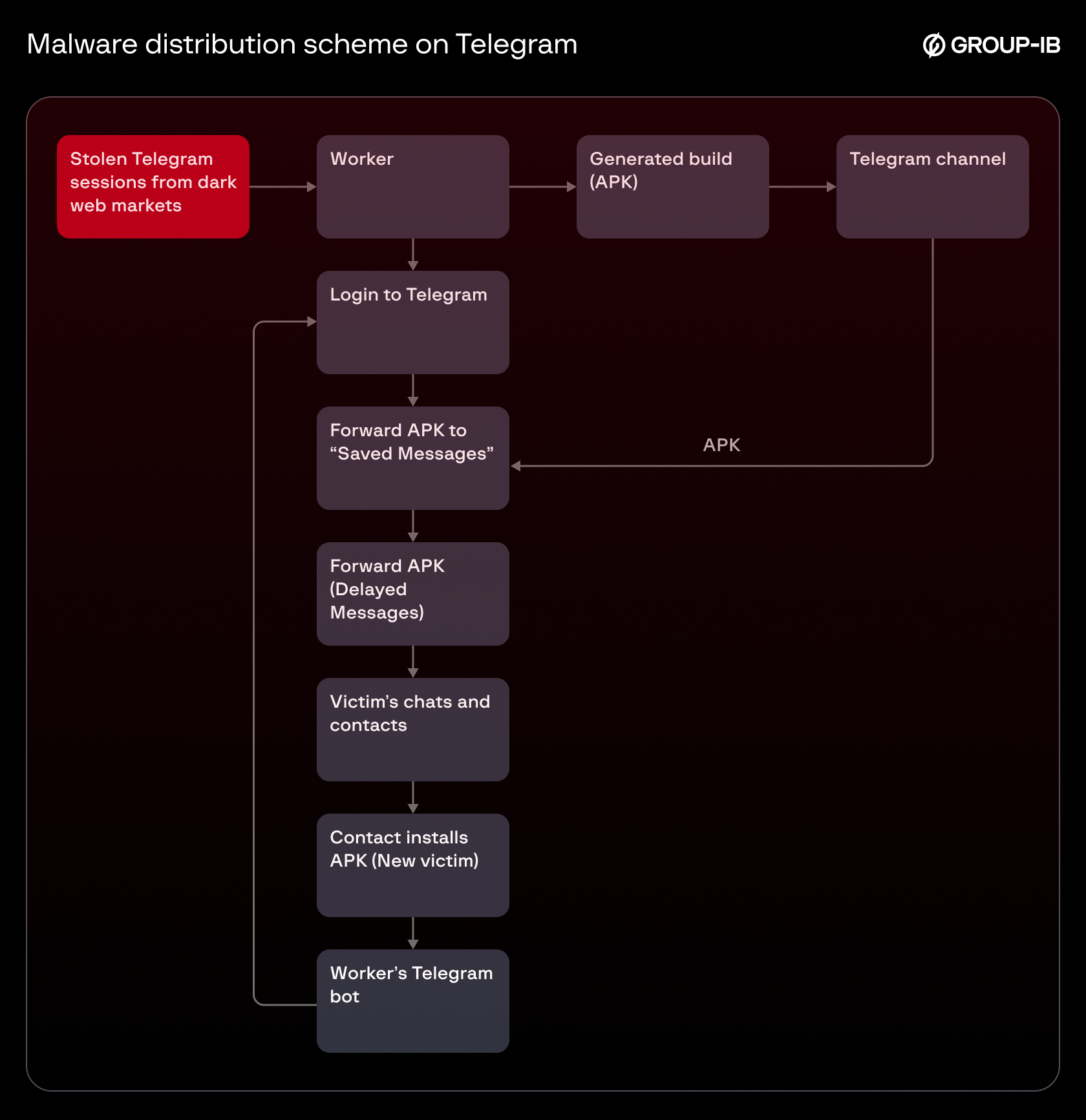

During research, following methods used by threat actors have been identified:

- The malicious APK file is sent to the Telegram channel

- The threat actor logins to the victim’s Telegram account using a stolen Telegram session.

- The APK is forwarded from the Telegram channel to the victim’s “Saved Messages” (stolen Telegram session).

- The APK from “Saved Messages” is being forwarded to the victim’s contacts using the delayed-send function.

When a victim installs the APK and provides the permissions, the attackers hijack the phone number and attempt to log into the Telegram account registered with that phone number. If the login succeeds, the distribution process is repeated, creating a cyclical infection chain.

Figure 10. Malware distribution scheme on Telegram.

An alternative Telegram client such as “Graph Messenger” (Telegraph) and Telegram X play a crucial role in this process. Telegram has function to forward message to all contacts, while Telegram X allows login primarily via SMS and can wipe its cache entirely, bypassing login limits or cases where authentication codes are not delivered.

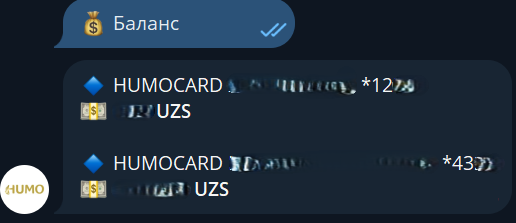

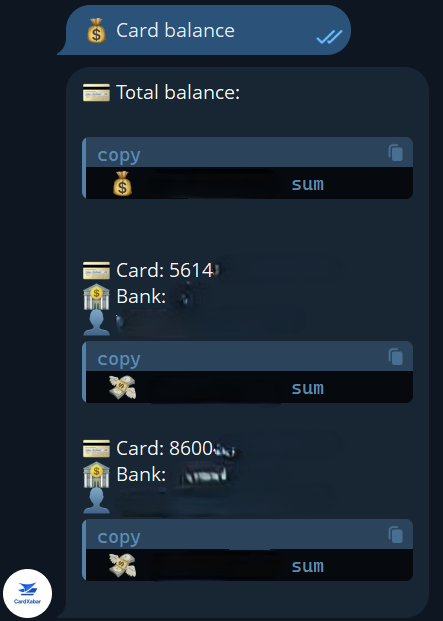

Beyond spreading the malware, attackers actively search in the victim’s account for bank cards that match the Telegram account name. They also register with legitimate Telegram bots issued by payment systems, such as @HUMOcardbot and @CardXabarBot to harvest card numbers and balances tied to phone numbers registered in Telegram. Card details are then further relayed to the vbivers.

Figure 11. Examples of response from legitimate Telegram bots.

Figure 12. Examples of response from legitimate Telegram bots.

Later iterations of the stealer gained the ability to access the victim’s contacts and send SMS messages directly from the compromised device. Since SMS cannot carry APK attachments, the attackers provide a link to a Telegram channel in the message, encouraging the victim to download the malware.

Profits made by a single cybercriminal group in 2025 are more than $2M based on the data posted in their Telegram channel – this confirms the significant impact of the evolution of SMS stealers in the region.

Bidirectional communication

Historically, Android SMS stealers in Uzbekistan lacked technical sophistication. The standard modus operandi was strictly linear: infect the device, collect basic metadata, and exfiltrate SMS logs.

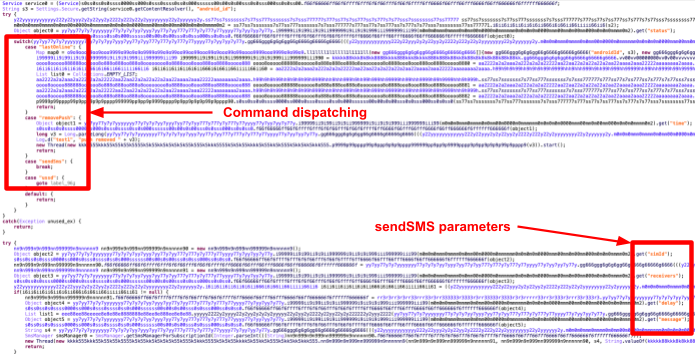

We observed a divergence from this trend in a previously unreported family: Wonderland (initially tracked as WretchedCat since H2 2024). Unlike regional predecessors that relied on stateless, one-way transmission, modern Wonderland samples implement the WebSocket protocol for bidirectional C2 communication. This architecture transforms the malware from a passive data stealer into a remote-controlled agent. The screenshot below illustrates code block dispatching incoming commands.

Figure 13. Wonderland C2 command handling.

While other regional stealers rely on hardcoded carrier-specific USSD-codes to retrieve device phone numbers, Wonderland executes arbitrary USSD-requests issued by C2. This flexibility negates the need for updates to support new carriers and enables advanced techniques, such as enabling call forwarding on the fly.

Additionally, the malware can send arbitrary SMS messages and temporarily hide push notifications. The SMS capability facilitates lateral movement. The notification hiding serves to suppress OTPs or security alerts during active fraud.

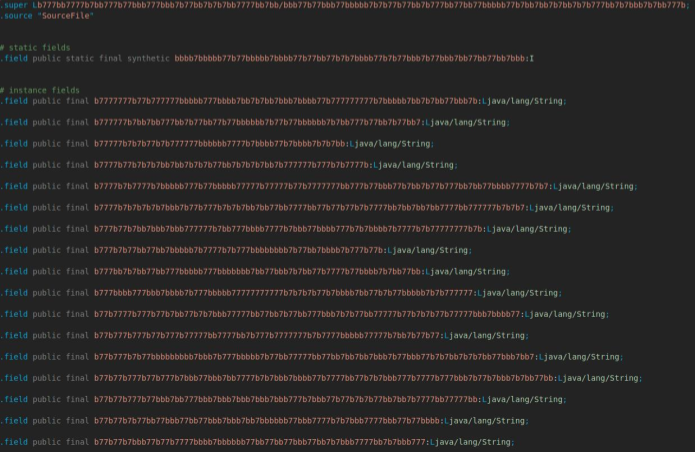

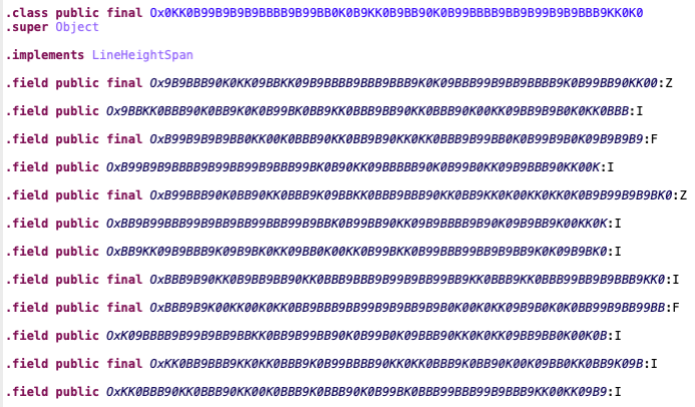

Obfuscation

Modern samples of currently active malware families in the region show that threat actors adopted a new obfuscation technique, as illustrated in the screenshots below.

This method replaces class and package names both for malware’s own code and third-party dependencies with long strings. These strings consist of repetitive characters and numbers, making it difficult for human analysts to distinguish between names.

Sandboxing detection

Beyond code obfuscation, recent variants are hardened against dynamic analysis. Alongside standard emulator checks, the malware now implements root and Frida (a dynamic instrumentation tool) detection. These checks ensure the application runs only on unmodified devices, explicitly excluding models popular among security researchers.

The malware responds to detection with immediate termination. It invokes the finish() method to close its activities. This prevents analysts and sandboxes from interacting with the application and capturing network traffic.

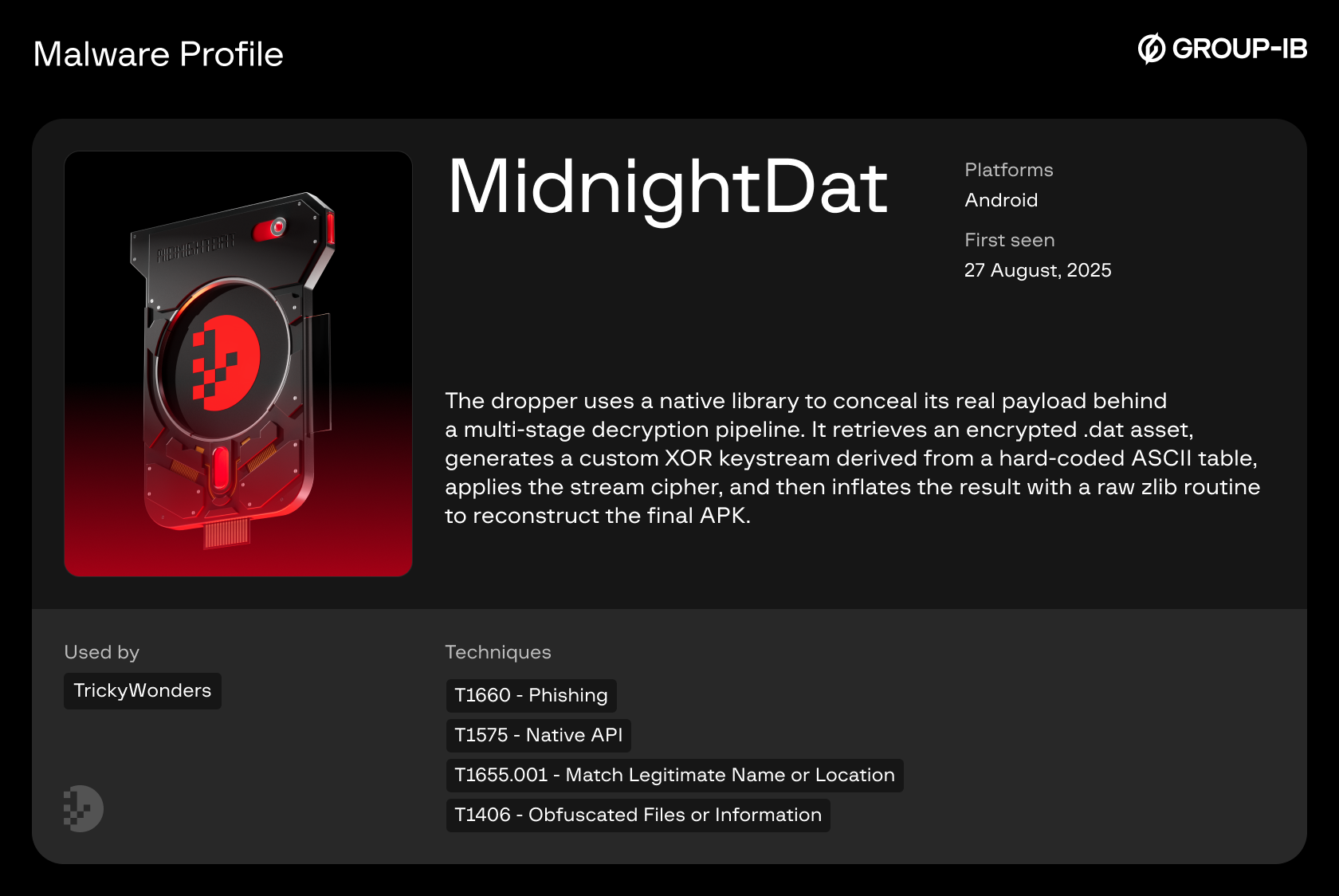

MidnightDat dropper

MidnightDat is a dropper that stores the main stealer payload inside an encrypted .dat file bundled in the application’s assets. This data blob contains a second-stage APK, but it is not stored in a readable format to complicate static analysis. Instead, the file is processed through multiple layers of protection.

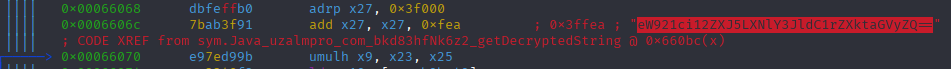

Before accessing the asset, the dropper decrypts the .dat filename with a native function getDecryptedString(str). This function takes the encrypted string and returns its plaintext version.

The getDecryptedString() method is implemented entirely in the native library libandroidcore_native.so. It performs:

- Base64 decoding of the encrypted string data.

- XOR decryption using a constant ASCII key embedded inside the native binary.

Figure 15. Embedded ASCII key

- Returning the final UTF-8 plaintext string.

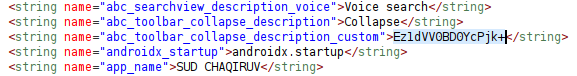

The initial string for the .dat filename is hidden in resources with the name abc_toolbar_collapse_description_custom which is ‘Ez1dVV0BD0YcPjk+’ in one of the analyzed samples.

Figure 16. Input string for .data filename

The decrypted filename is then used with AssetManager in another native function that decrypts the .dat itself to a final payload:

- Reads the entire encrypted asset into memory, obtaining both the total size and a direct pointer to the encrypted buffer.

- Applies XOR-based decryption using a custom keystream. The key table is embedded in .rodata and is identical to the one used in getDecryptedString():

eW921ci12ZXJ5LXNlY3JldC1rZXktaGVyZQ== (used as raw ASCII bytes, not Base64-decoded).

Each byte of the payload is XORed with a pseudorandomly indexed byte from this table. - Once the XOR stage is completed, the function decompresses the buffer using zlib, calling inflateInit2_ with version “1.2.8”, windowBits = 0x1F (gzip mode).

- It then iteratively feeds data to inflate, expanding the output through an internal allocator until decompression finishes.

- After a successful inflate cycle, the function finalizes the stream with inflateEnd and returns the rebuilt buffer.

As a result, the decompressed buffer is a valid APK file – final sms stealer.

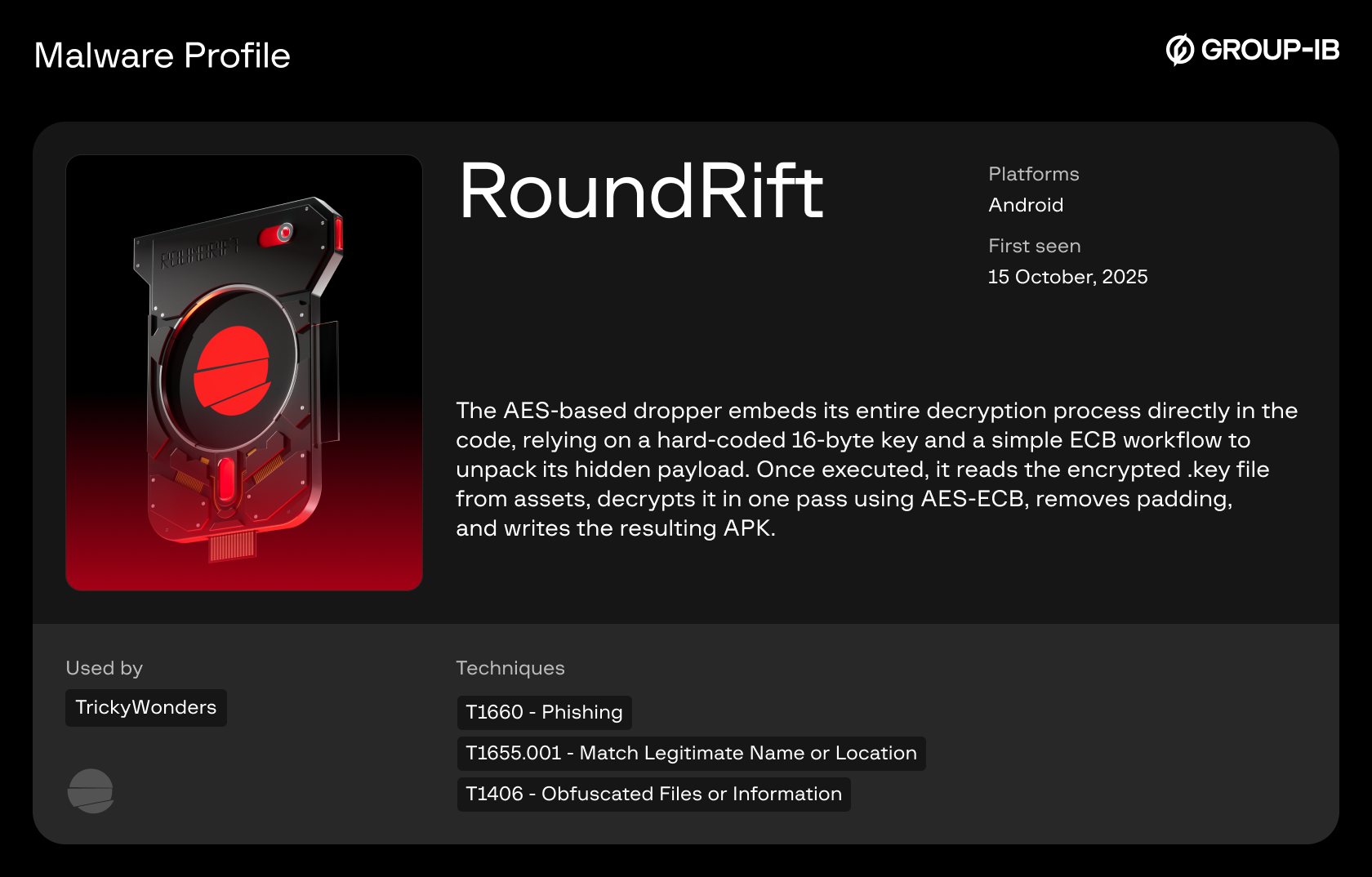

RoundRift dropper

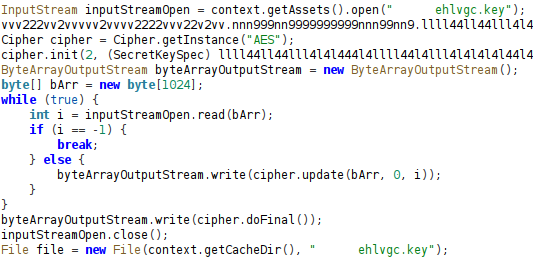

RoundRift is a dropper that also contains a much simpler decryption mechanism used for extracting an embedded secondary payload stored in the asset file [name].key.

Unlike the native .dat unpacker, this stage is fully implemented in Java and relies on a straightforward AES routine without any obfuscation or dynamic key generation.

Inside the dropper code, the file is opened through context.getAssets().open(“[name].key”), and the contents are passed to a standard Cipher object configured as AES with a static 16-byte value key.

Figure 17. APK Decryption Block

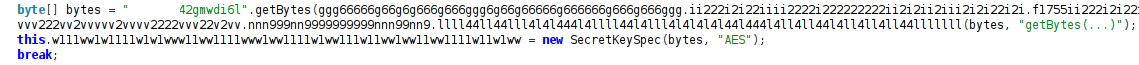

Key material is embedded directly in Java as a SecretKeySpec, not derived or transformed.

Figure 18. AES value key

The dropper reads the entire encrypted buffer, and writes the decrypted output to the app’s cache directory. The resulting file is a fully decrypted APK, which is then pushed into the PackageInstaller session and installed silently through the usual staged-installation technique.

Prevention

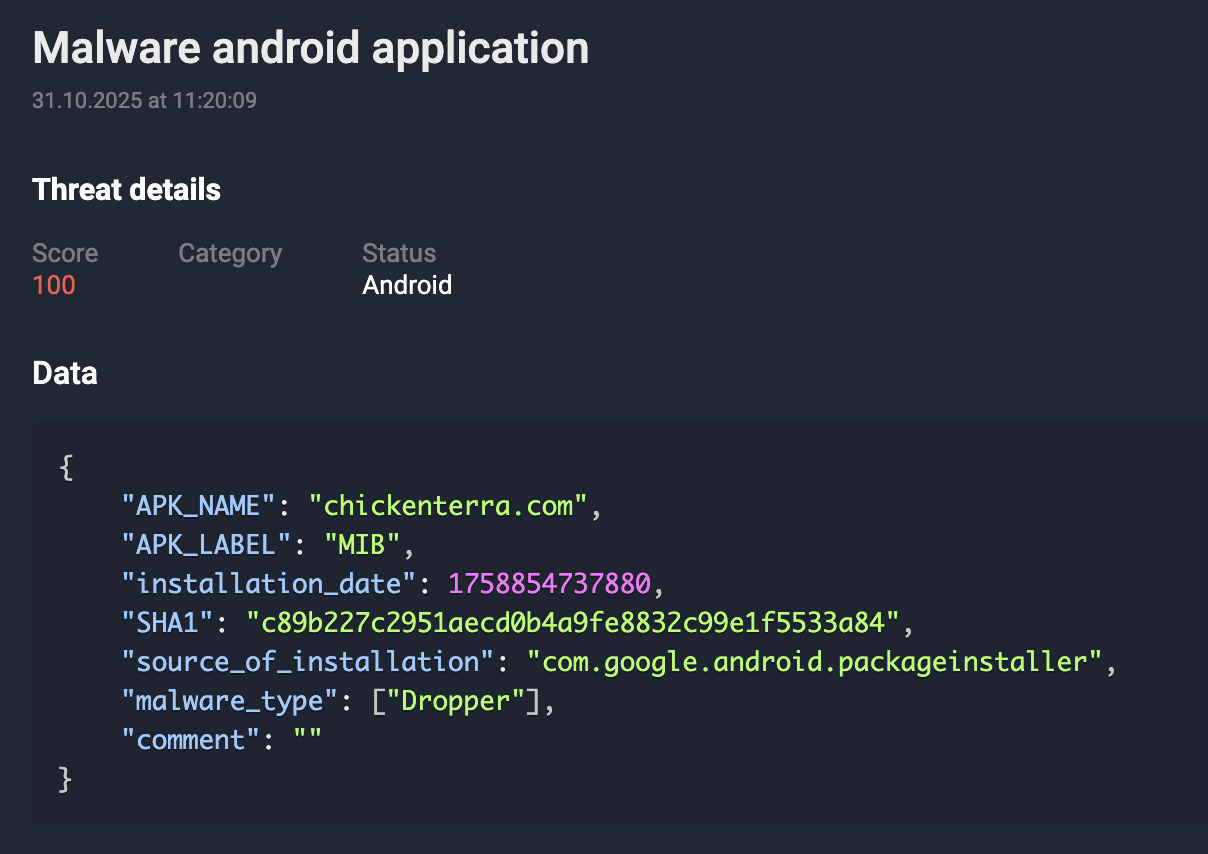

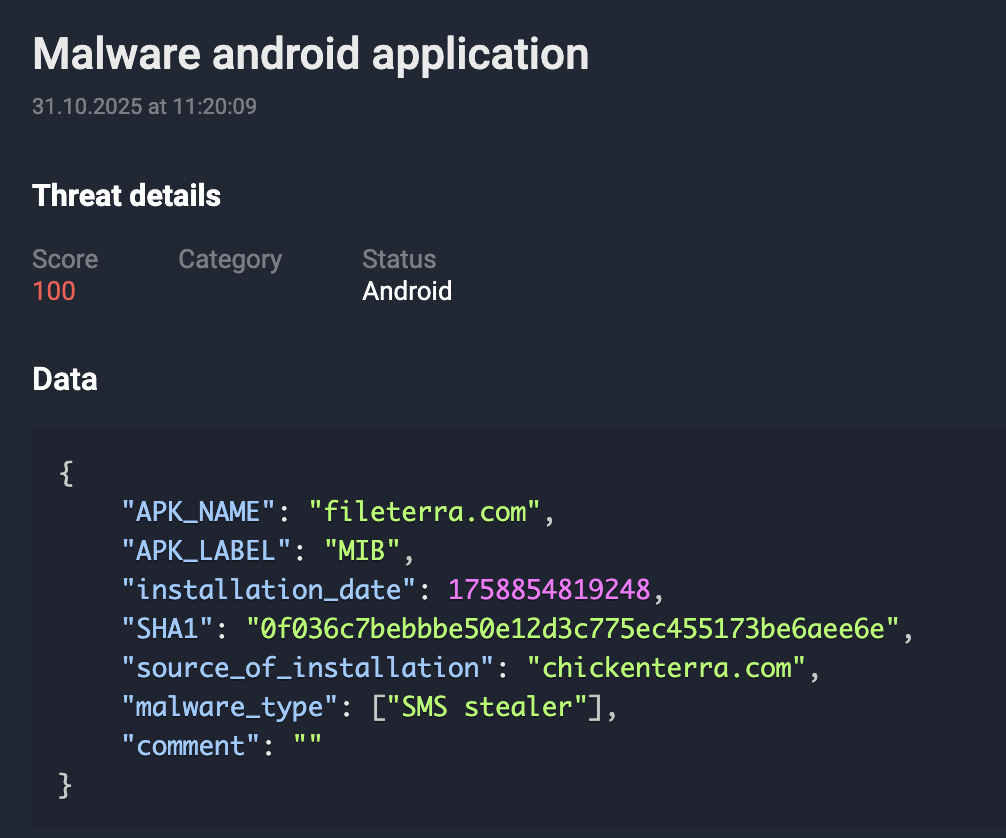

Group-IB Fraud Protection regularly develops new methods for detecting malware and improves existing ones, using an extensive database and experience accumulated worldwide to ensure effective and timely protection for Group-IB customers. All available application parameters are analyzed, and anomalies and inconsistencies are searched for, allowing new threat samples to be detected instantly.

For Dropper samples:

Group-IB Fraud Protection maintains an extensive database of all detected malware, which identifies patterns for detecting various categories of malware, with developed rules for the effective detection of dropper software at the earliest stages of infection.

For SMS stealer samples:

Although the method of delivering the Trojan to the device has changed significantly, Fraud Protection rules are still effective at detecting the SMS stealer itself, regardless of whether we know about the dropper application or other delivery methods are used. In this example, we can see that the SMS stealer was installed by a dropper that was detected earlier.

Conclusion

The new wave of malware development in the region clearly demonstrates that methods of compromising Android devices are not just becoming more sophisticated – they are evolving at a rapid pace. Attackers are actively adapting their tools, implementing new approaches to distribution, concealment of activity, and maintaining control over infected devices.

Despite targeted countermeasures, the threat is not only continuing unabated, but also continues to cause significant damage to both users and financial institutions. New families of malware are emerging, infection chains are becoming more complex, and attacks are becoming more automated and scalable.

In such conditions, it is critically important to implement coordinated and unified response measures. These measures should cover both current incidents and known malware samples, as well as potential threats that have not yet been identified. This involves strengthening monitoring, consolidating analytics sources, proactively identifying anomalies, and regularly adapting protective measures to new techniques used by attackers.

Only a comprehensive and coordinated approach will minimize risks and increase the resilience of regional digital infrastructure to the growing wave of mobile cyber threats.

Recommendations

To protect against droppers and any other mobile stealers, we advise end users and businesses to apply the following risk mitigation recommendations.

For Businesses

- Deploy a user session monitoring system such as Fraud Protection to detect infected devices, unusual account activity and logins from suspicious devices.

- Notify the user about device infection and respond before funds are stolen.

- Utilize Threat Intelligence services to ensure continuous monitoring of active and evolving malware campaigns.

For End-Users

- Pay close attention to notifications inside the financial app.

- Do not store bank card details in plain text or within messaging apps.

- If you suspect that your device is infected, it is recommended that you disconnect from the Internet and reset it to factory settings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is an Android dropper and how does it work?

Android droppers are specially built applications (APKs) that hide a malicious payload internally. It installs without requesting dangerous permissions and later unpacks the embedded stealer locally, bypassing real-time security checks.

How big is the financial damage?

One of the cybercriminal groups monitored by Group-IB stole more than US$2 million since January 2025.

How is the malware distributed?

Distribution relies primarily on Telegram. Attackers use stolen Telegram sessions to forward malicious APKs to victims’ contacts. Additional channels include fake Google Play pages, social media ads, and dating platforms that trick users into installing apps.

What is the Wonderland Android SMS-Stealer?

Wonderland is a new SMS-stealer family with real-time, bidirectional WebSocket communication. It can execute arbitrary commands, send SMS messages, issue USSD requests, and hide notifications, giving attackers active control over the device.

Why are droppers now preferred by attackers?

Droppers achieve higher infection rates because they avoid suspicious permissions, are heavily obfuscated, and are generated through automated pipelines that constantly change package names and indicators, rendering static detection ineffective.

What applications do droppers impersonate?

Droppers often pose as videos, photos, court letters, or invitations, frequently using double extensions like “video.mp4.apk” to appear legitimate and entice victims to install them.

How can users avoid infection?

Users should avoid installing APKs sent via Telegram or SMS, stay alert to unusual notifications in banking apps, avoid storing card details in messengers, and keep Play Protect and Android security features enabled.

What should users do if they installed a stealer?

They should disconnect from the internet, back up important data, perform a factory reset, reinstall only trusted apps, change credentials, and contact their bank if financial data may be compromised.

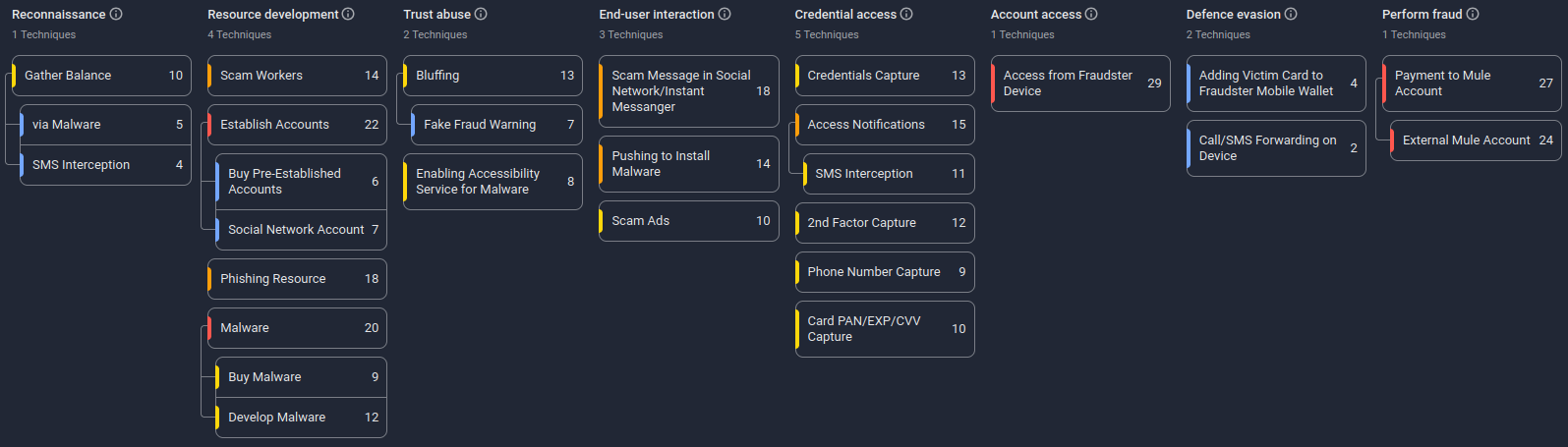

Fraud Matrix

Get Started with Group-IB’s Fraud Matrix. If you are not yet registered in our system, we invite you to do so.

| Tactic | ID | Technique | Procedure |

| Reconnaissance | T2103.002 | Via Malware | Fraudsters use malware to gain access to user information. |

| Reconnaissance | T2103.003 | SMS Interception | Malware gathers information about victims’ balances through intercepted SMS messages. |

| Resource development | T2165 | Phishing Resource | The malicious files are being distributed using fake Google Play web pages. |

| Resource development | T2031.001 | Develop Malware | Fraudsters develop or modify mobile malware to steal SMS and support credential theft. |

| Resource development | T2031.002 | Buy Malware | Fraudsters acquire mobile malware from underground markets or vendors to use in further attack stages. |

| Resource development | T2023.003 | Social Network Account | The malicious files are being distributed using fake accounts on dating sites. |

| Resource development | T2023.006 | Buy Pre-Established Accounts | Fraudsters utilize stolen telegram sessions of Uzbek users sold on darkweb markets to spread the malware. |

| Resource development | T2007 | Scam Workers | Fraudsters are organized similarly as the “classiscam” groups. |

| Trust abuse | T2077.009 | Fake Fraud Warning | Fraudsters impersonate reputable organizations via calls or texts to warn victims of fake account issues (court notices, past-due loans, or fraudulent transactions). |

| End-user interaction | T2177 | Pushing to Install Malware | Fraudsters require users to download, install the malicious .APK file manually. |

| End-user interaction | T2156 | Scam Ads | The malicious files are being distributed via advertisement campaigns on social networks. |

| End-user interaction | T2158 | Scam Message in Social Network/Instant Messenger | Fraudsters send fraudulent messages via social networks and messengers to deliver phishing links or malicious APKs. |

| Credential access | T2067 | Card PAN/EXP/CVV Capture | Fraudsters capture the victim’s card PAN/EXP/CVV through phishing forms in malicious apps and in the “saved messages” data in stolen Telegram accounts. |

| Credential access | T2180 | Credentials Capture | Fraudsters intercept or collect user credentials through malware applications. |

| Credential access | T2001.001 | SMS Interception | Fraudsters intercept inbound SMS messages on the victim’s device to obtain OTP codes, authentication links, or security alerts. |

| Credential access | T2039 | 2nd Factor Capture | Fraudsters capture OTP via malware to bypass MFA. |

| Credential access | T2124 | Phone Number Capture | Fraudsters collect the victim’s phone number through malicious apps to enable targeted authentication interception or account takeover. |

| Account access | T2069 | Access from Fraudster Device | Fraudsters log in to the victim’s account from their own controlled device to initiate fraudulent actions. |

| Defence evasion | T2040 | Adding Victim Card to Fraudster Mobile Wallet | Fraudsters add the victim’s payment card to a fraudster-controlled mobile wallet to bypass device-binding controls and enable unauthorized transactions. |

| Perform fraud | T2034.001 | External Mule Account | Fraudsters transfer funds to mule accounts held at external financial institutions to move stolen money outside the victim’s bank. |

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

File Hashes

| Filename | SHA-1 | Malware |

| Sud Qarori.PDF (8).apk | db1d14d5246f2c8807c55084b74247dea6465285 | Wonderland |

| Razdevator.apk | 6f5502b0e2e99d5f9be4e5f9dcf3fa21b48a92e4 | Wonderland |

| Sud qarori26.08.2025.apk | 516943e93a2bd8f7d91dc5d8b130073d60f4fe67 | Wonderland |

| Siz bilan video (212).apk | 6ab99f2396f309647f1adabd290f711960d41696 | Wonderland |

| Toyga Taklifnoma (2).apk | 3343e72eb3f04244c7ebf464883cb120365e3a4e | Wonderland |

| SUD CHAQIRUV.apk | 916c66810f0c1ffb447ac98c8e707c75aa911b4f | MidnightDat |

| Toy Video Albom 2025.apk | 85605b32c2a61c258709a19a54cb8a2aa59f8f04 | MidnightDat |

| Toy_VideoAlbom_2025.apk | 23cb06e1d97b951b36b77b0e7c38ccedb1f9ea2d | MidnightDat |

| TashkentGirls_.apk | e2ca86efebc6338a37cdcc0f07ea5d1e8eeeb53a | MidnightDat |

| SudIlovasi.apk | 2dd2371efced160743d88ef08905e3eb7aa83531 | MidnightDat |

| toydan videо.apk | c8b8415ee68ec26af544d2ec9d5b8e86e6670690 | RoundRift |

| To’ydan video2025 (2).apk | d5b1e45cdf941e5e5771b50881e167dea8020b18 | RoundRift |

| Kamera_yozuvi_2025-10-26.apk | 86ee96cd11cf08f37a511fa860c78b12cb237b73 | RoundRift |

| to’ydan video (2025).apk | 22b7bc9bdccbdac0ec40cf8cedaf7bce3b313e94 | RoundRift |

| to’ydan video (2025).apk | 9374204e405814cd2a0f364272cf1b417a9b0163 | RoundRift |

DISCLAIMER: All technical information, including malware analysis, indicators of compromise and infrastructure details provided in this publication, is shared solely for defensive cybersecurity and research purposes. Group-IB does not endorse or permit any unauthorized or offensive use of the information contained herein. The data and conclusions represent Group-IB’s analytical assessment based on available evidence and are intended to help organizations detect, prevent, and respond to cyber threats.

Group-IB expressly disclaims liability for any misuse of the information provided. Organizations and readers are encouraged to apply this intelligence responsibly and in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.

This blog may reference legitimate third-party services such as Telegram and others, solely to illustrate cases where threat actors have abused or misused these platforms.