Introduction

The fraud campaign involving fake Coretax apps represents a sophisticated, industrialized threat targeting Indonesia’s digital public infrastructure. Initiated in July 2025 and experiencing a significant escalation in January 2026 — timed to coincide with the national tax season — the campaign leverages the impersonation of the official Coretax web platform to facilitate large-scale financial fraud.

The attack chain integrates phishing websites, social engineering (WhatsApp), malicious APK sideloading, and voice phishing (vishing) to achieve full device compromise and unauthorized transfer execution.

Group-IB operational analysis reveals that the campaign is mainly orchestrated by the GoldFactory threat cluster, utilizing a shared infrastructure to deploy multiple malware families, including Gigabud.RAT and MMRat. By abusing over 16 trusted brands across government and financial sectors, the threat actors have scaled their operations horizontally, resulting in an estimated nationwide financial impact of USD 1.5 million to USD 2 million in Indonesia alone.

This blog details the operation behind the Coretax campaign in Indonesia as well as uncovers the regional and even global implications of the malware’s modular infrastructure.

Despite the sophistication of these tactics, the implementation of advanced predictive modeling and behavioral detection has proven effective, maintaining a fraud success rate as low as 0.027% among institutions protected by Group-IB, underscoring the necessity of evolving beyond silo reactive detection towards intelligence-led, predictive defence frameworks.

Key discoveries

- Exploitation of National Tax Season: A highly synchronized campaign was launched to exploit the 2026 Indonesian tax season, targeting a potential pool of 67 million residents.

- Industrialized Horizontal Scaling: The threat infrastructure was not limited to tax services but simultaneously abused over 16 trusted brands, resulting in a systemic financial impact of USD 1.5 million to USD 2 million.

- Sophisticated Malware Proliferation: Group-IB researchers identified 228 new malicious samples belonging to the Gigabud.RAT and MMRat families, significantly enriching the global signature database.

- GoldFactory Attribution: The campaign was definitively linked to the GoldFactory threat cluster, revealing a shift toward unified, cross-border infrastructure to amortize development costs.

- Efficacy of Predictive Modeling: By utilizing proactive infrastructure mapping, fraud success rate(with money loss) by protected clients was neutralized to a record low of 0.027% among malware compromised devices.

- Cyber Fraud Fusion Agility: The end-to-end orchestration of Group-IB FP, TI, CERT, and Investigation teams delivered a comprehensive analysis of the threat campaign.

Who may find this blog interesting:

- Cybersecurity Analysts and Corporate Security Teams.

- Malware Analysts

- Threat Intelligence Specialists

- Cyber Investigators and Law Enforcement

- Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERT)

- Financial Compliance and Risk Officers

Group-IB Threat Intelligence and Fraud Intelligence Portals:

Group-IB customers can access our Threat Intelligence portal for more information about the threat actor and malware mentioned in this blog, and Fraud Intelligence portal for a complete list of IOCs detected in this campaign:

Threat Actor Profile

Malware Profile

Malware Profile

Threat Overview

What is Coretax?

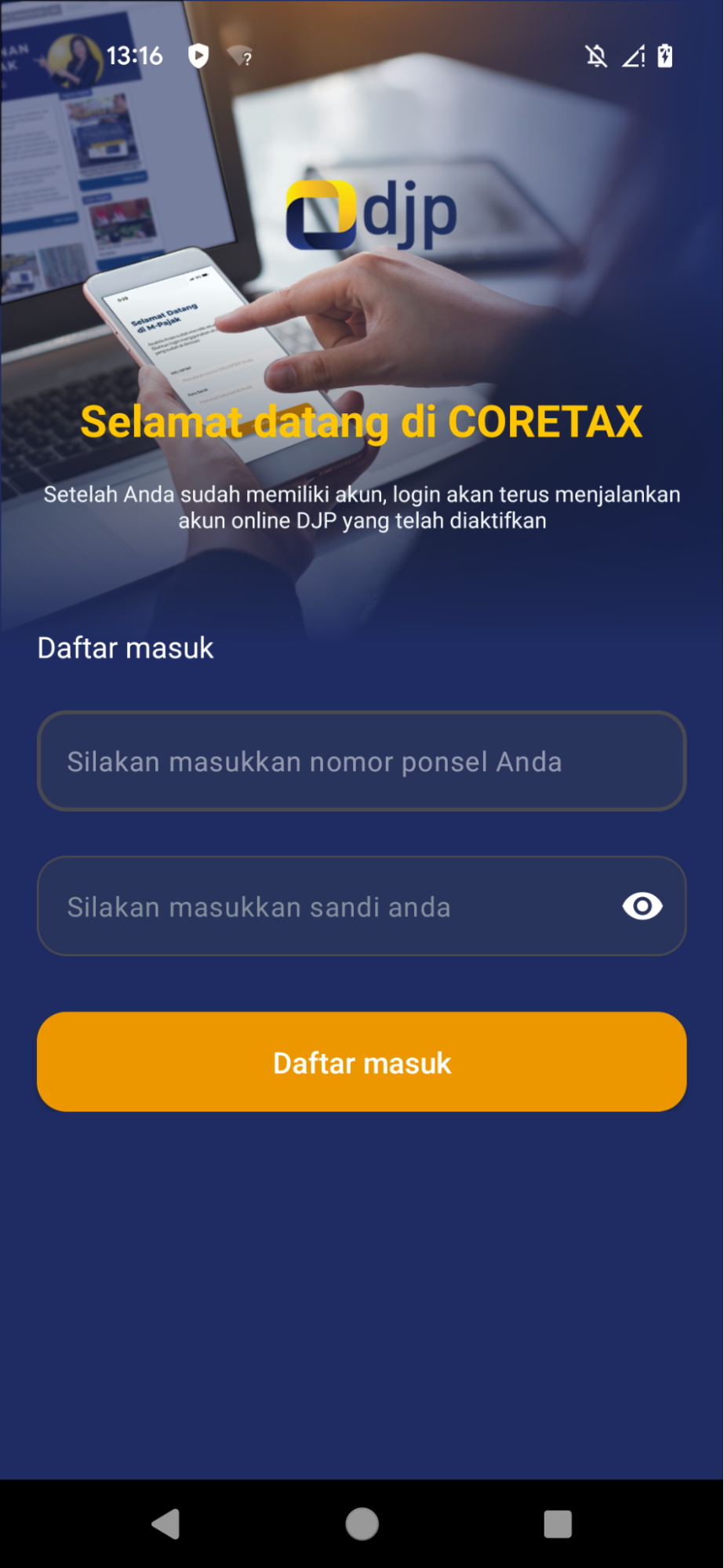

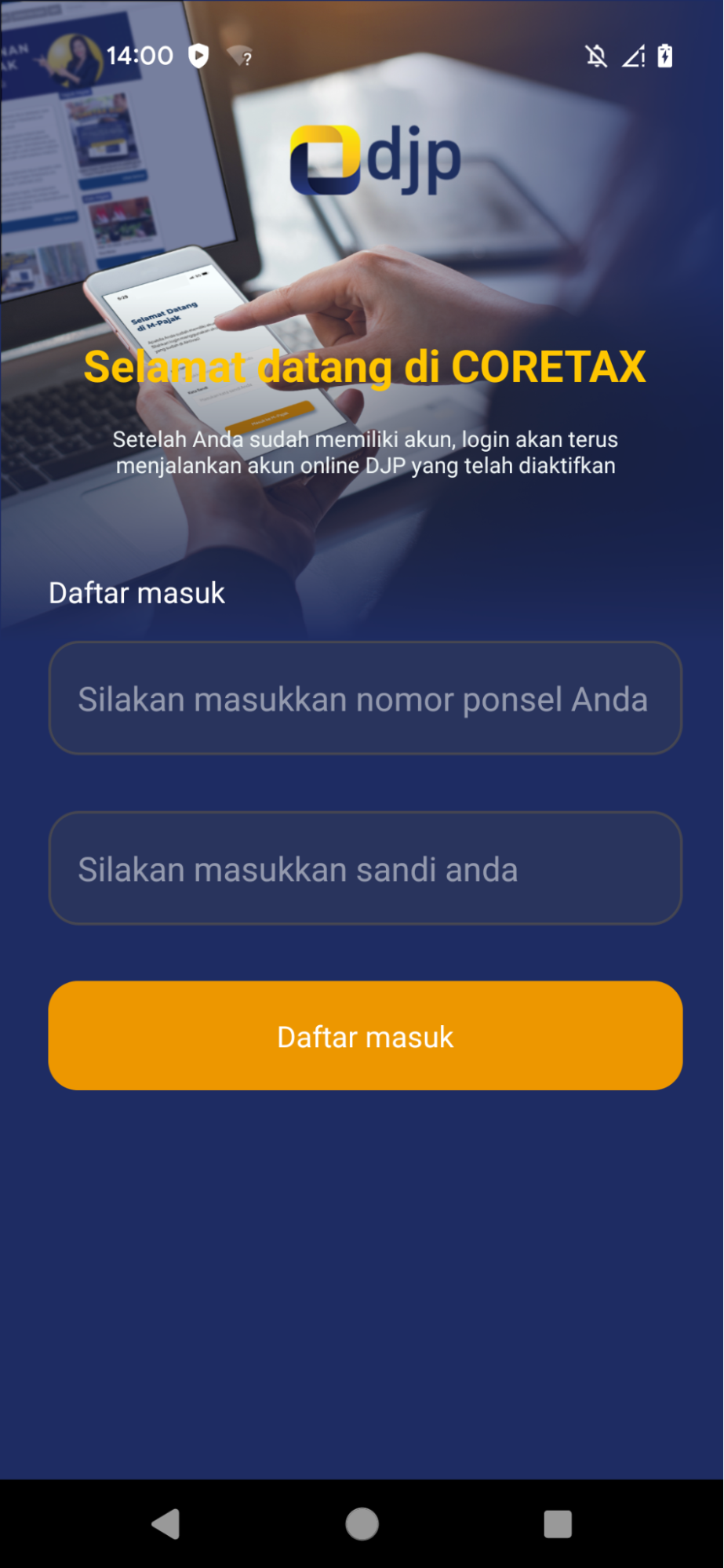

Coretax (coretaxdjp.pajak.go.id) is an official Indonesian tax payment platform used by residents to submit and settle tax obligations. At the time of analysis(Jan 2026), the Coretax service is accessible exclusively via web interface and does not offer any official mobile application.

Consequently, applications labeled as Coretax or CORETAX circulating in Indonesia are highly likely fraudulent impersonations of the legitimate tax platform. These applications are distributed as part of a malware campaign designed to deceive users into installing malicious software.

Targeting scope and timing

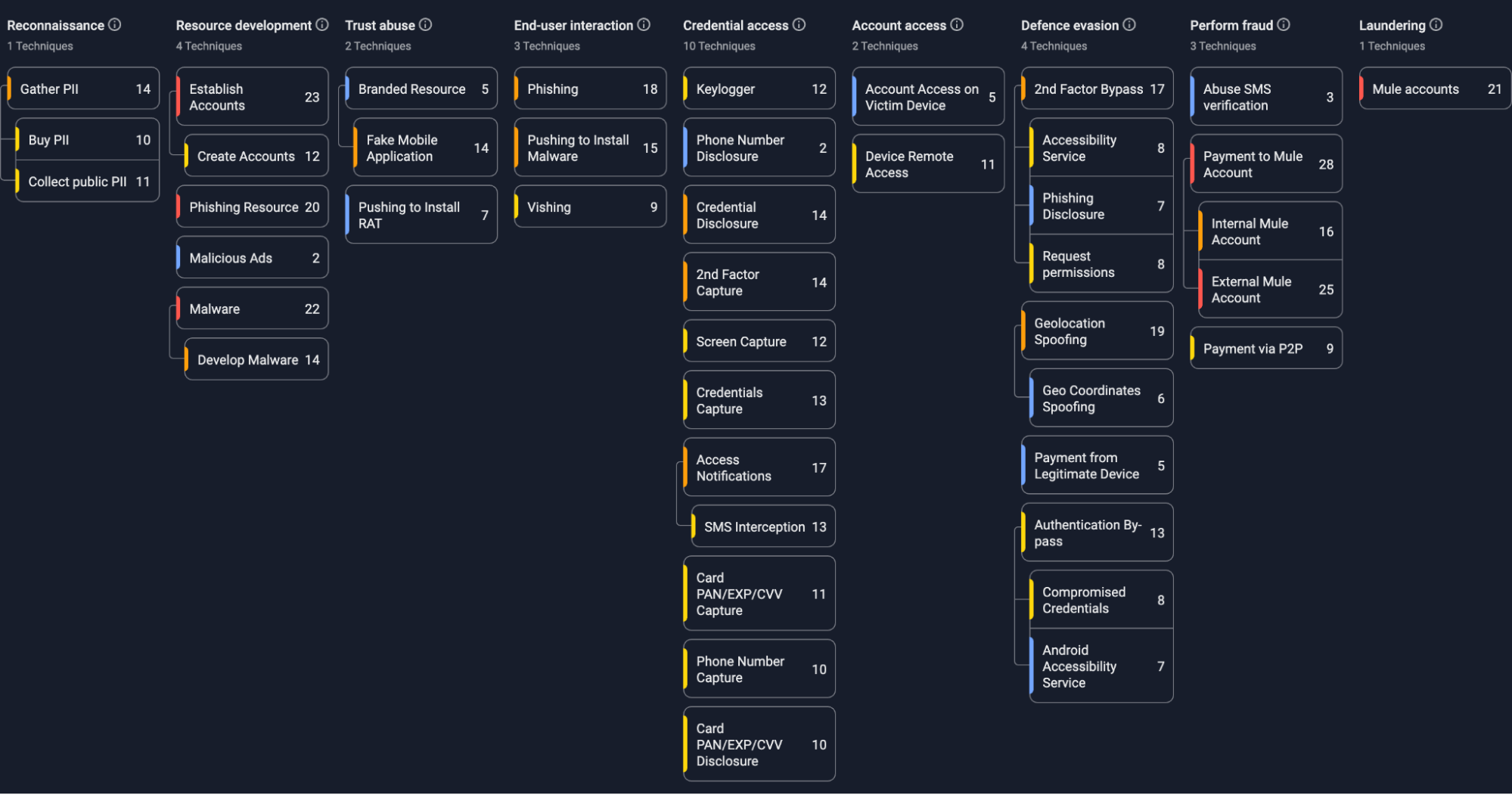

Figure 1. Count of daily unique devices installing fake Coretax apps.

Attack chain & operational flow

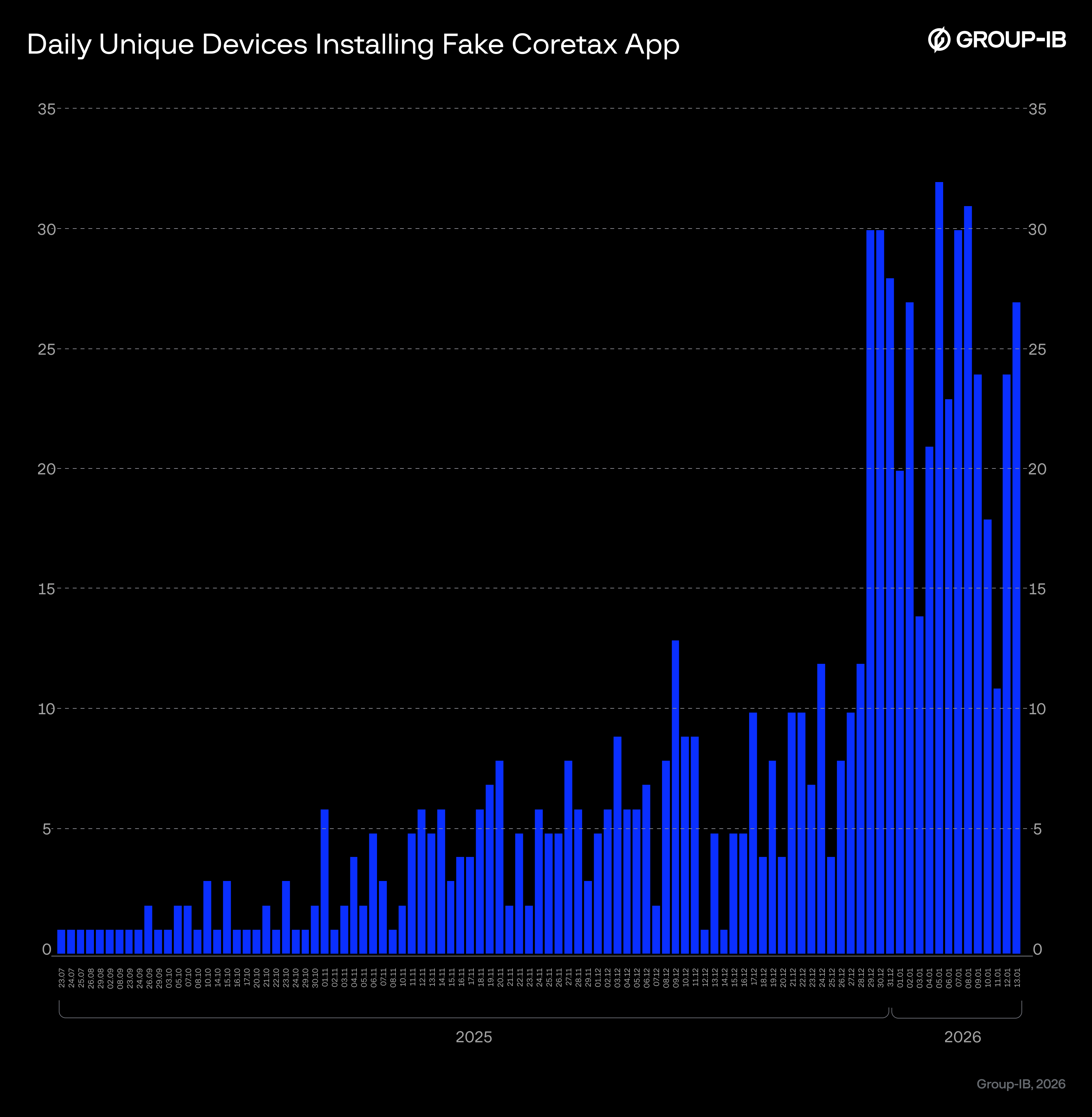

The observed attack combines phishing websites, WhatsApp tax officer accounts impersonation, vishing, screen recording, and remote access trojan (RAT) capabilities. Each stage of the attack is described in detail below:

Figure 2. Fake Coretax app attack timeline.

Stage 0 : Reconnaissance & resource development

- Fraudsters develop malware and generate phishing URLs.

- Collection of personally identifiable information (PII) from potential targets. This deduction is corroborated through victim interviews, who have conveyed to Group-IB investigators that fraudsters impersonating tax officials already had their personal information and text details.

Stage 1 : Initial lure & social engineering

Fraudsters create fake WhatsApp accounts impersonating Indonesian government tax authorities (DJP) and send victims messages containing malicious download links for a fake “Coretax” application, exploiting Indonesia’s current tax return season.

Stage 2 : Malware installation & device compromise

After the victim installs the fake Coretax app:

- The victim’s device becomes temporarily frozen or black-screened, likely to delay user response and hide malicious background activity.

- During the device freezing phase, the malware harvests sensitive device information (e.g., phone number, device identifiers).

- Additional malicious components or applications are silently downloaded to expand control and obscure attacker attribution.

Stage 3 : Voice phishing (vishing) escalation

The fraudster then calls the victim, impersonating a government tax officer, and pressures the victim to pay the alleged outstanding tax immediately, leveraging urgency and authority.

Stage 4 : Credential & financial data capture

While guiding the victim through the “payment” process during the call:

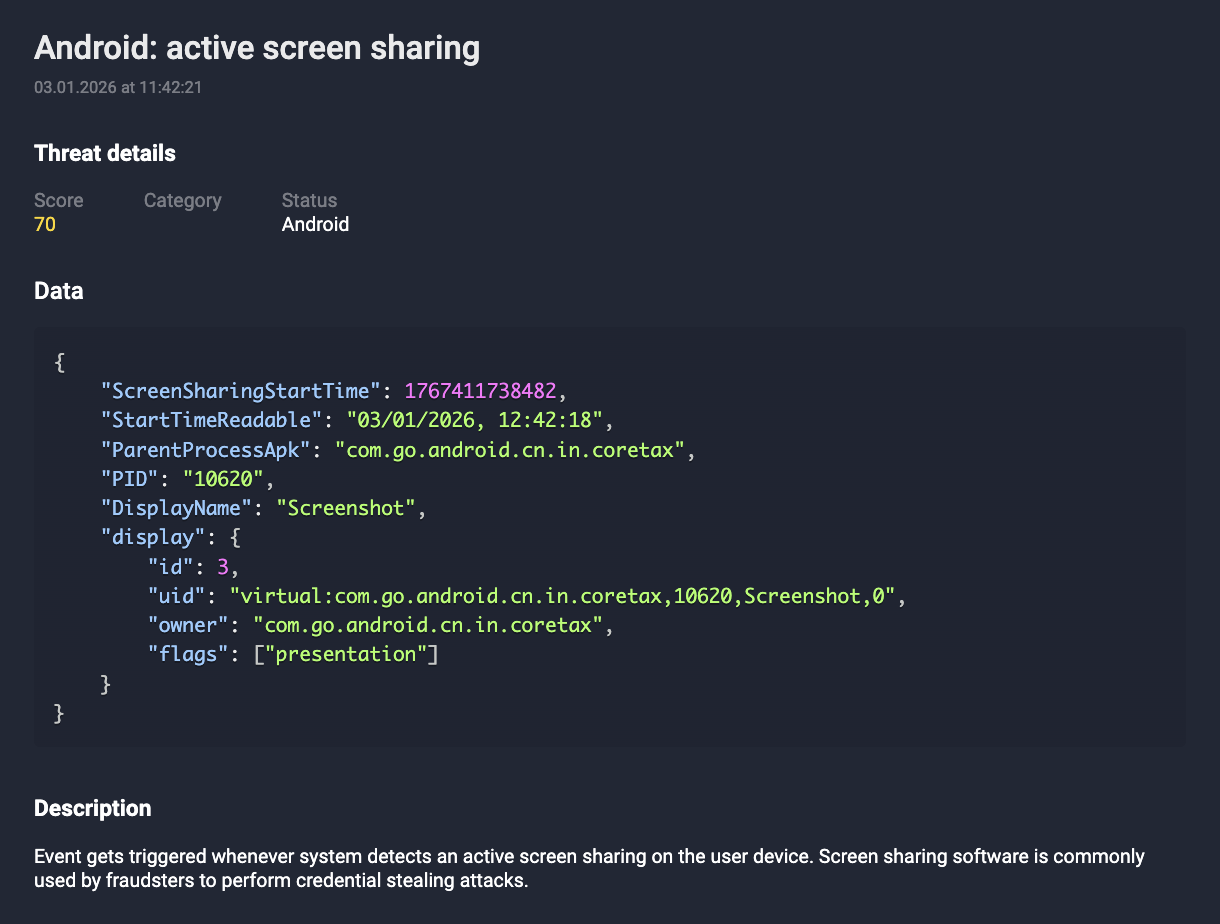

- The malware records the device screen, capturing bank login credentials, OTPs, and other sensitive financial information.

- This step enables full compromise of the victim’s banking credentials.

Stage 5 : Account takeover & financial theft

After the call ends:

- The attacker uses remote access capabilities to control the victim’s device.

- The fraudster logs into the victim’s bank account and conducts large unauthorized transactions, resulting in direct financial loss.

- The stolen funds are then funneled through a complex mule network making it difficult to trace and recover.

Impact Assessment

Financial impact

During the investigation, a device compromise rate of 0.025% was observed among Group-IB Indonesian clients’ bank systems, meaning approximately 2.5 out of every 1,000 bank user devices may be affected by the fake malicious Coretax apps.

By extrapolating this device compromise rate nationwide together with the financial loss feedback from Indonesia clients, Group-IB fraud analysts estimate the nationwide financial impact associated with the fake Coretax application to the 67 million Indonesian tax residence to range between USD 330,000 and USD 340,000 in January 2026 alone, accounting for both direct customer losses and bank operational costs.

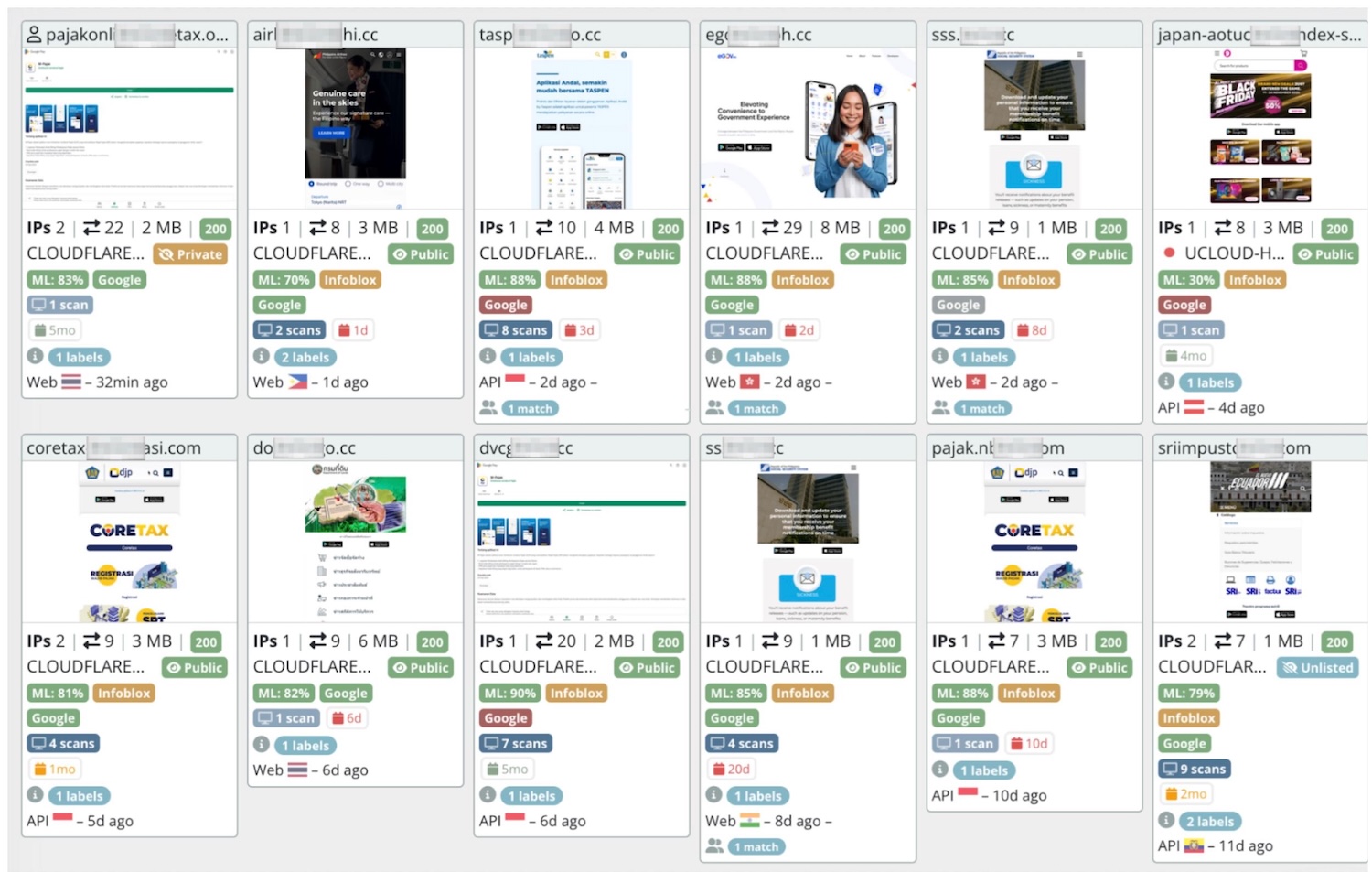

Further analysis indicates that the malware infrastructure supporting this fraud campaign is not limited to a single impersonated service. The same infrastructure has been observed actively abusing more than 16 trusted brands, collectively targeting Indonesia’s broader population of approximately 287 million.

These impersonated brands span multiple critical sectors, from tax payment services to business licensing platforms, national identity systems, airlines, pension funds, insurance providers, energy companies, immigration services, social security programs, and civil servant services. All identified fake applications in this investigation share overlapping malware components, delivery mechanisms, or command-and-control (C2) infrastructure consistent with the Coretax campaign.

| Fake APP | Impersonated Brand | Industry |

| M-Pajak | M-Pajak (DJP) | Tax Payment / Government |

| OSS | OSS (Online Single Submission – BKPM) | Business Licensing / Government |

| Identitas Kependudukan Digital | Dukcapil (Digital Population ID) | National Identity / Government |

| FlyGaruda | Garuda Indonesia | Airline / Transportation |

| Taspen | Taspen | Pension Fund / SOE |

| My Taspen Life 3.0 | Taspen / Taspen Life | Pension / Insurance |

| HiPajak | Direktorat Jenderal Pajak (DJP) | Tax Payment / Government |

| MyPertamina | Pertamina | Energy / Fuel (SOE) |

| M-Paspor | Direktorat Jenderal Imigrasi | Immigration / Government |

| PajakInd | Direktorat Jenderal Pajak (DJP) | Tax Payment / Government |

| DJP | Direktorat Jenderal Pajak | Tax Authority / Government |

| Otentikasi | Government Authentication Service (Generic) | Digital Identity / Authentication |

| Signal | SIGNAL (Samsat Digital Nasional) | Vehicle Tax / Government |

| JMO | BPJS Ketenagakerjaan (JMO App) | Social Security / Employment |

| MyASN | BKN / ASN Digital Services | Civil Servant Services / Government |

| Andal by Taspen | Taspen | Pension Fund / SOE |

By applying the observed Coretax device compromise rate (~0.025%) and adopting a conservative activation assumptions to the wider Indonesian population (287 millions) exposed through these additional abused brands, Group-IB analysts further aggregates the financial impact across all impersonated services is estimated to range between USD 1.5 million and USD 2 million, accounting for direct financial losses, as well as indirect costs attributable to investigation, remediation, regulatory response, and customer support.

Systemic impact on the digital ecosystem and society

Beyond immediate fiscal depletion, the Coretax campaign demonstrates that a single, shared malware infrastructure can simultaneously abuse multiple trusted brands, enabling threat actors to amortize development costs and scale fraud horizontally across an entire national digital ecosystem. This capability significantly increases systemic risk and poses long-term challenges to the integrity of Indonesia’s digital landscape.

Malware campaigns targeting critical digital services — including tax platforms, licensing systems, and national identity programs — extend their impact beyond credential theft or transactional fraud. Such operations undermine public trust in digital government infrastructure, which is a foundational requirement for successful digital transformation and service adoption.

Erosion of trust in official digital services may result in reduced user engagement, slower adoption of e-government initiatives, and increased reliance on offline processes, thereby weakening the efficiency gains these systems are designed to deliver. Even users who are not directly affected may alter their behavior due to perceived security risks, creating broader ecosystem-level effects.

These risks are further amplified by the persistence and reusability of the underlying threat infrastructure. Behind each campaign sits an industrial-scale infrastructure that doesn’t disappear after one incident. It remains in place, ready to pivot to new targets, ensuring that the threat continues to evolve and spread.

The repeated attacks create a dangerous sense of resignation. Citizens grow tired of constant warnings and breaches. The digital space starts to feel hostile by default, and users become less willing to engage with legitimate services — not because they don’t see the value, but because they do not feel safe. It creates a feeling of being watched, exposed, and manipulated. When privacy is violated at scale, it results in a shared vulnerability that weakens confidence in technology and the systems meant to safeguard society.

Malware Attribution

Group-IB FP and TI teams have analyzed the fake Coretax campaign and identified three distinct malware families. The primary threat actor behind this campaign appears to be GoldFactory.

Readers can learn more about GoldFactory from our initial report “Face Off: Group-IB identifies first iOS trojan stealing facial recognition data” and an updated deep dive into their mobile fraud campaigns “Hook for Gold: Inside GoldFactory’s Сampaign That Turns Apps Into Goldmines”.

Group 1: Gigabud.RAT

Gigabud.RAT is a sophisticated Android trojan specifically designed to impersonate government entities and financial institutions. First documented in July 2022, Gigabud is attributed to the GoldFactory threat cluster and its operational scope has expanded from Thailand to include the Philippines, Vietnam, Peru, and Indonesia.

- Technical Mechanisms: Gigabud gathers sensitive data primarily through continuous screen recording and accessibility service abuse. It is capable of bypassing multi-factor authentication (MFA) and executing Automated Transfer Systems (ATS), allowing for unauthorized financial transactions directly from the victim’s device.

- Campaign Specifics: During the Coretax campaign, 211 previously unobserved Gigabud samples were identified. These samples exhibit incremental variations while maintaining core Gigabud functionality.

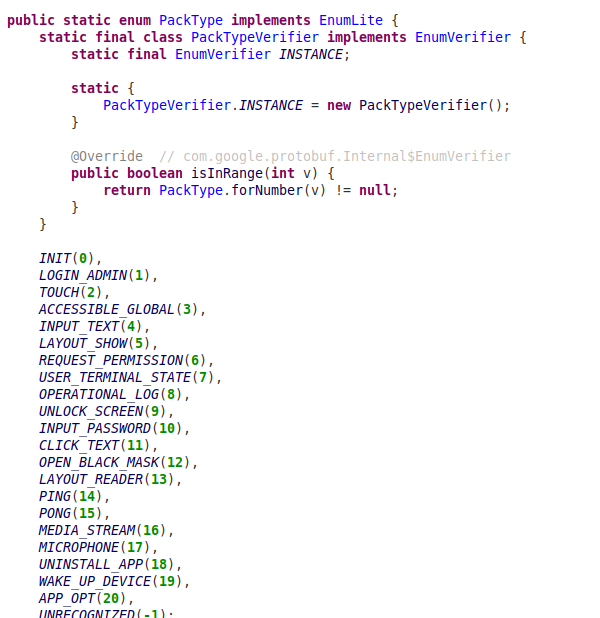

Group-2: MMRAT

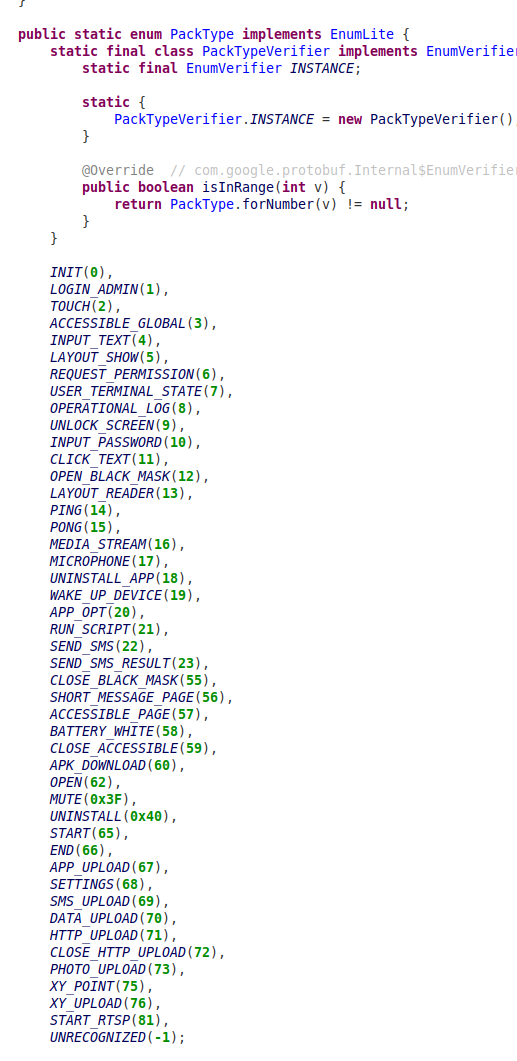

MMRat was first detected in July 2023. It is a high-performance Android banking trojan that facilitates total remote device control. It is distinguished by the usage of a customized Command-and-Control (C2) protocol implemented via Protocol Buffers (Protobuf), which optimizes data exfiltration and command execution efficiency.

- Attribution to GoldFactory: Based on extensive infrastructure overlap, shared landing pages, and similar targeting patterns, MMRat is also attributed to the GoldFactory threat cluster. Compared with samples detected in 2023, the latest MMRAT malware used in Coretax campaign has more C2 commands, indicating the continued evolution of this malware.

- Operational Integration: Within the Coretax framework, six new MMRat samples were detected. The usage of both MMRAT and Gigabud suggest a “horizontal scaling” strategy where the threat actor utilizes different malware families with similar core capabilities as interchangeable modules within a single campaign to increase the probability of infection.

Group 3: Taotie Malware Family

A third group of malware samples identified during this fraud campaign could not be conclusively attributed to a known family at the time of analysis. It seems like a new banking malware by Chinese-speaking developers which has never been seen before. The Group-IB research team named this malware cluster Taotie and it consists of eleven unique samples, all of which have yet to be marked as malicious by other public tools and services such as Virustotal at the time of writing. Taotie is currently under active investigation by Group-IB researchers. To support early intervention, Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) associated with Taotie have been integrated into the detection engines detailed in the following section.

Analysis of Phishing Infrastructure and Distribution

Phishing URLs distributing fake Coretax apps

Phishing URLs serve as the primary distribution mechanism for the fraud campaign involving fake Coretax apps. These URLs are typically short-lived, a deliberate tactic used to reduce traceability, evade automated detection, and limit exposure to takedown actions.

One confirmed distribution domain, pajak[.]abfigo[.]cc, was identified delivering Group-1 (Gigabud.RAT) malware samples. Forensic analysis of the underlying web source code revealed Chinese-language comments, a finding that is consistent with the established profile of the GoldFactory threat group.

// 或者 append 到任何需要的父元素

console.error('获取数据失败:', error);

Historical data indicates that the earliest active phishing site surfaced in July 2025, a timeline that aligns with the initial fake Coretax app detections recorded by Group-IB’s Fraud Protection team. An expanded list of verified phishing URLs can be found in the Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) section below.

Phishing website design and behavioral patterns

Through the analysis of the hosting environment and functional logic of the Coretax phishing pages, Group-IB CERT analysts have identified reusable design patterns. This discovery facilitated the identification of 996 additional phishing URLs generated by the same threat actor infrastructure, leading to two conclusions:

- Multinational targeting & diverse sectors : The identified URLs are not restricted to the Coretax brand or Indonesian entities, but also brands across Thailand, Vietnam, Philippines, and even South Africa, covering sectors including government administration, transportation and ticketing, energy utilities, aviation, food and e-commence.

Figure 6. Regional phishing URLs detected with the same infrastructure as the fraud campaign involving fake Coretax apps in Indonesia.

- Industrialized Generation Framework: The evidence suggests the operation of a centralized malware-as-a-service (MaaS) infrastructure. A dedicated generation framework is utilized to facilitate the rapid creation and rotation of regionalized domains, allowing the threat actor to scale operations horizontally across different jurisdictions with minimal overhead.

Economic impact and global implications

The operational efficiency gained through this industrialized model significantly amplifies the campaign’s scalability.

- Global Financial Assessment: When the observed fraud rates from the main fraud campaign in Indonesia are extrapolated across multiple countries and sectors, the aggregate annual global financial impact is estimated to reach USD 6 million, accounting for direct theft, remediation, and the systemic costs of brand recovery.

- Money Laundering Networks: The cross-border nature of these operations and the high volume of illicit transactions indicate the involvement of organized money laundering syndicates. The complexity of the cash-out phase suggests that stolen funds are likely laundered through sophisticated networks that transcend national borders, necessitating coordinated intervention by international financial institutions and law enforcement agencies.

Malware Detection

The identification of threats within the fraud campaign involving fake Coretax apps is predicated on a multi-layered analytical framework. This infrastructure integrates technical indicators, application behavior analysis, and contextual intelligence to ensure a robust defense against evolving malware strains.

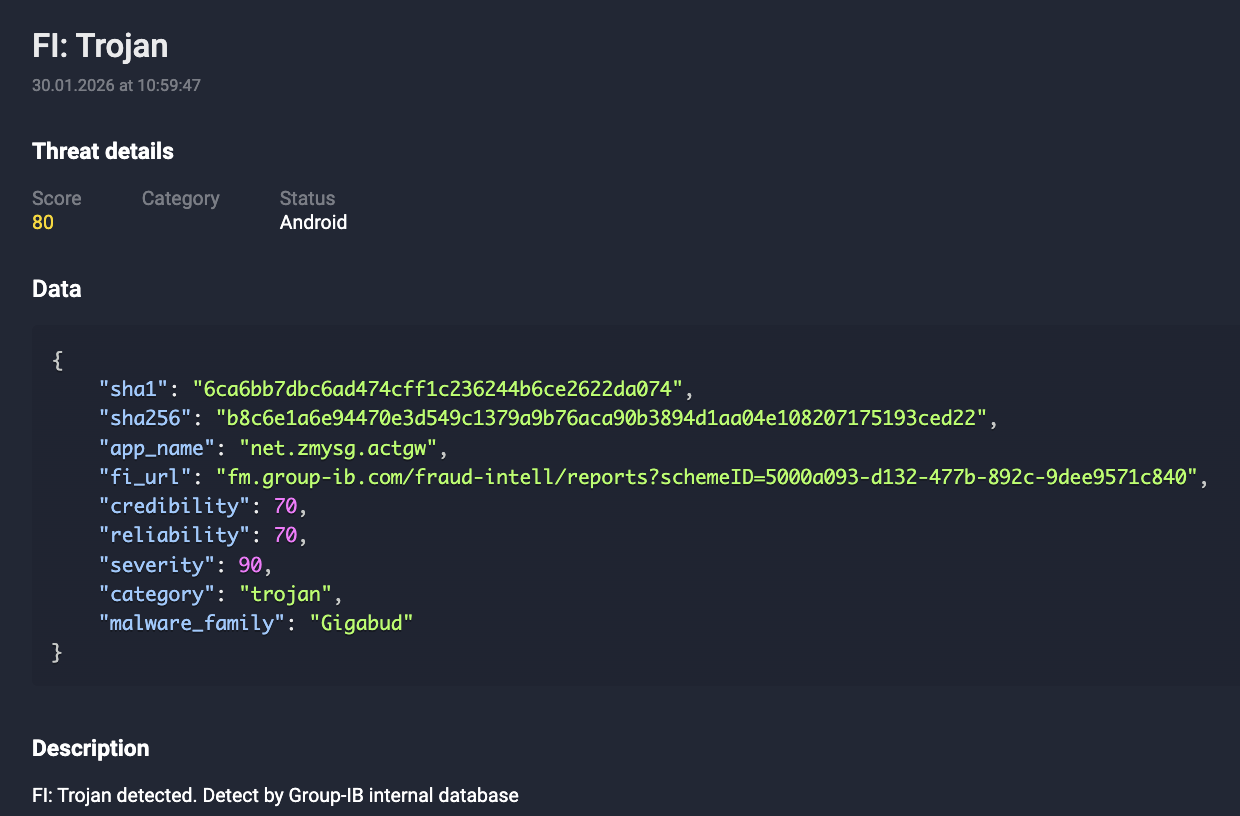

1. Signature-based detection

Signature-based detection is employed as a fundamental, reactive layer that relies on the identification of known malicious artifacts.

- Mechanism and Efficacy: Detection is achieved through the systematic comparison of file attributes against established malware databases. While this methodology is highly effective for the mitigation of known variants, its utility is inherently constrained when applied to novel or highly polymorphic families.

- Database Enrichment: The success of this approach is contingent upon the continuous ingestion of high-fidelity data. Real-time telemetry, sourced from both internal Fraud Intelligence (FI) repositories and global Threat Intelligence(TI) feeds, is utilized to maintain the relevance of these databases.

- Metadata Insights: Through Fraud Intelligence Trojan detection events, comprehensive metadata — including SHA-1 hash values, APK filenames, and malware family classifications — is provided to stakeholders, facilitating rapid identification and accelerating downstream incident response.

Figure 7. Signature-based detection of Gigabud malware sample attributed to Coretax.

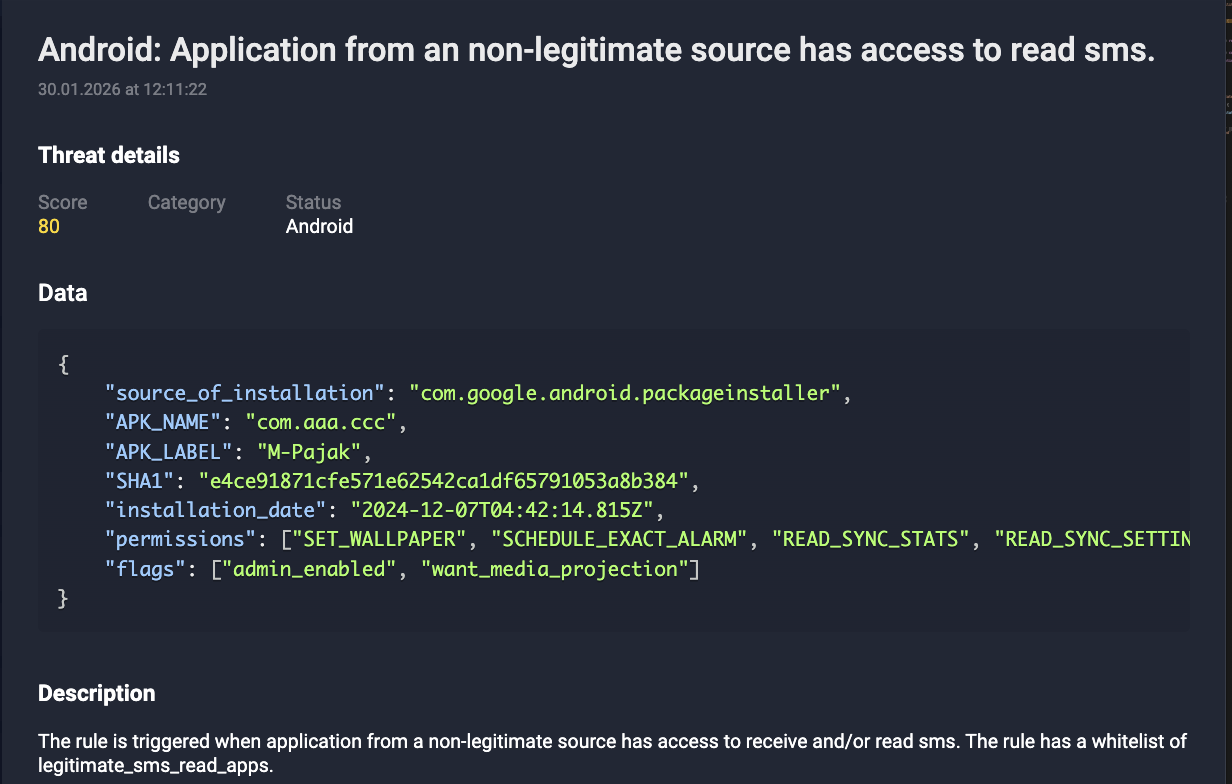

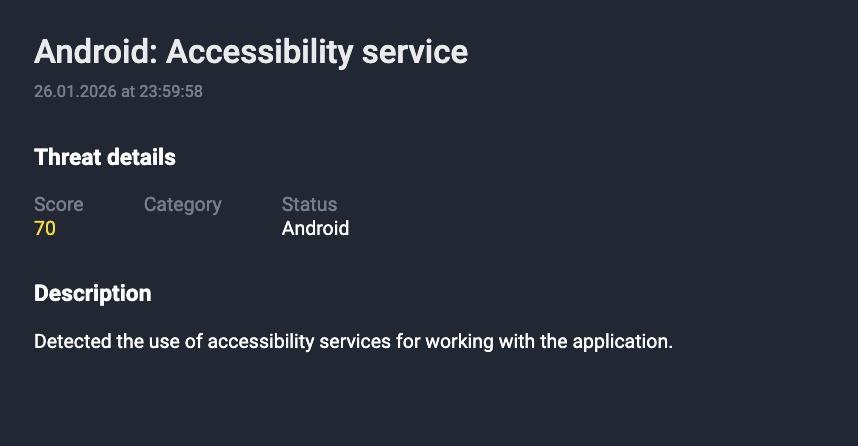

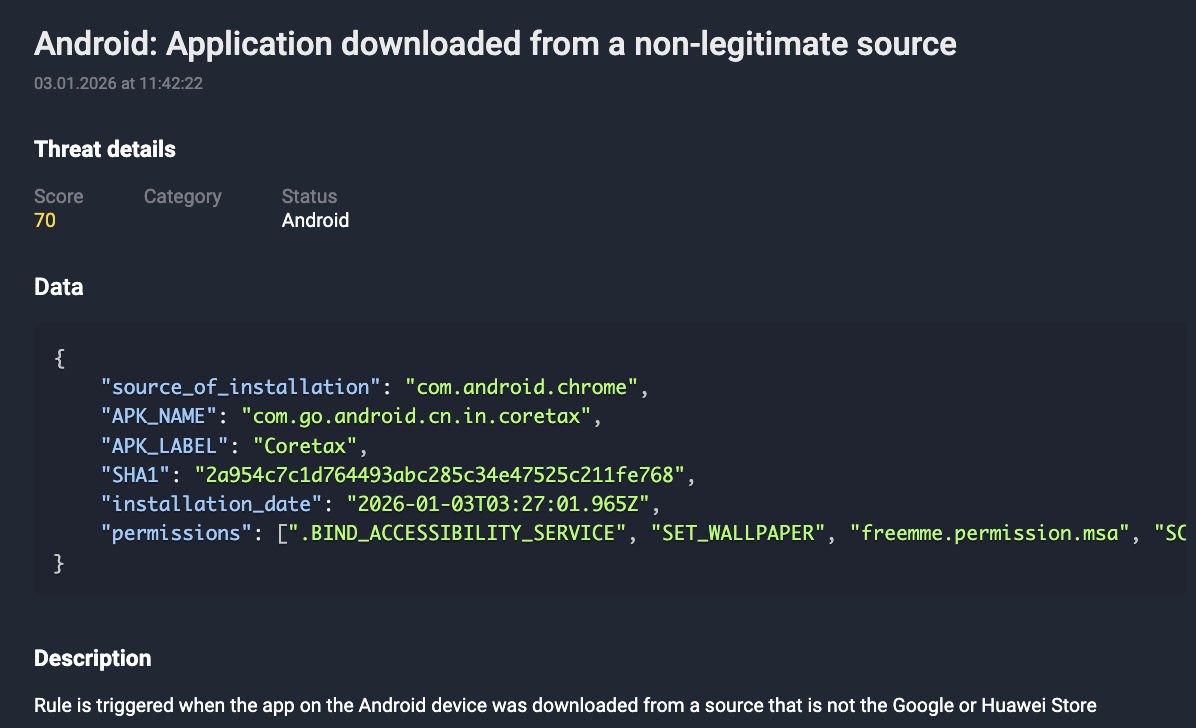

2. Application behavior–based detection

To address the limitations of static signatures, a proactive behavioral detection layer is implemented. This approach evaluates runtime activities associated with malicious functionality.

Key signals utilized in behavior-based detection include:

- Installation Source Profiling: Applications are downloaded for non-legitimate or “sideloaded” origin points, which are primary indicators of a compromised delivery chain.

Figure 8. Fake Coretax apps downloaded from a non-legitimate source.

- High-Risk Access Analysis: Particular emphasis is placed on the unauthorized request of Accessibility Services and SMS access, which are frequently abused by banking trojans for credential interception.

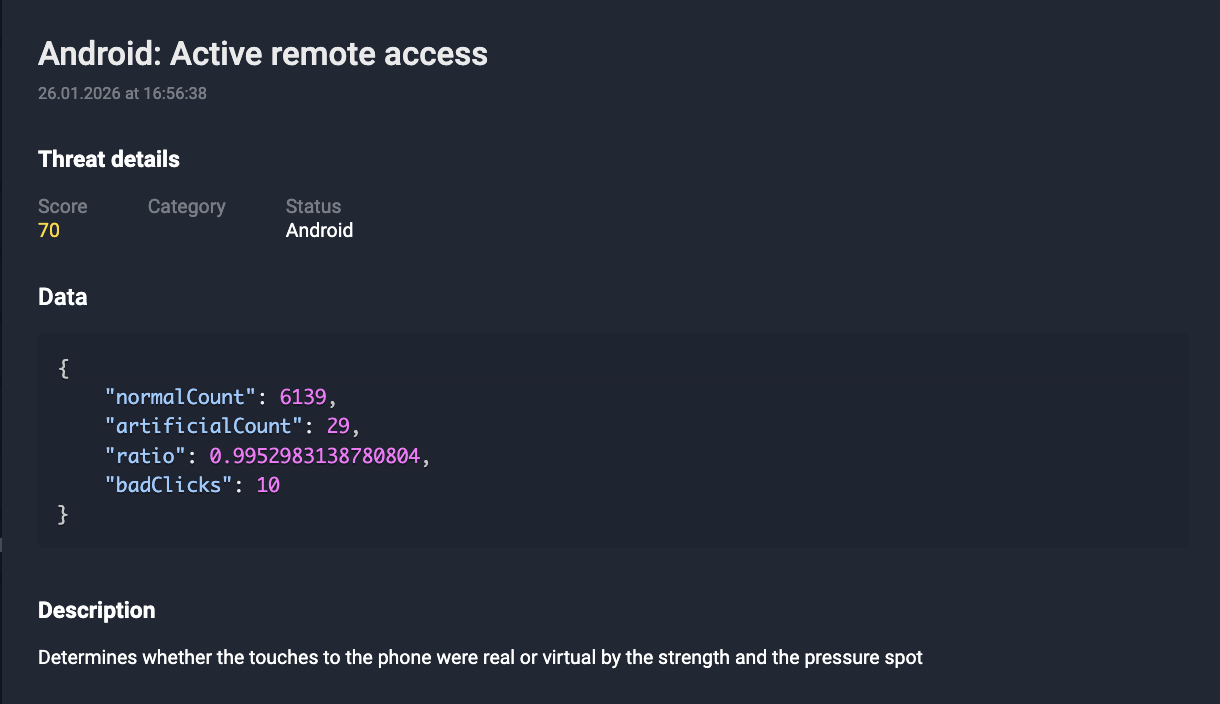

- Runtime Activity Monitoring: The detection of unauthorized screen recording, overlay injections, or remote access behaviors triggers immediate risk flags.

3. Human behavior analysis (contextual intelligence)

Human behavior analysis provides the critical context required to distinguish between legitimate user actions and those conducted under duress or through technical manipulation.

Within the fraud campaign involving fake Coretax apps, specific fraud patterns are correlated to establish high-confidence alerts:

- Telephonic Correlation: The presence of an active voice call (vishing) concurrent with application interaction.

- Technical Overlap: The confirmed presence of malware on the device during a session.

- Coerced Transaction Logic: The initiation of financial transfers following a period of suspicious device activity.

By correlating these behavioral signals, fraud analysts are better positioned to evaluate victim manipulation and make informed decisions regarding transaction blocking or reimbursement eligibility.

Fraud Prediction

While detection serves as a critical reactive control, the efficacy of a robust cybersecurity posture is fundamentally dependent on predictive capabilities. By anticipating threat actor trajectories before the execution phase, organizations can shift from damage mitigation to total loss prevention.

In the fraud campaign involving fake Coretax apps, the implementation of advanced predictive modeling resulted in a fraud success rate of just 0.027% among malware compromised devices by FP protected clients. This metric indicates that of every 1,000 malware compromised devices, approximately 997 were successfully neutralized before a financial loss could materialize.

The predictive framework utilized during the this fraud campaign involving fake Coretax apps include the following components:

- Real-time Behavioral Correlation and Account Securing: By synthesizing signals from the aforementioned malware detection layers — such as the presence of a known malware family and suspicious device telemetry — the following transactions are flagged as highly probable fraud in real time. Consequently, affected accounts are secured and malicious transactions are automatically rejected before the “cash-out” phase can be initiated.

- Forecasting Horizontal Campaign Scaling: An in-depth understanding of the GoldFactory threat actor profile allows for the prediction that Coretax is not an isolated target. A broader multi-brand campaign utilizing the same underlying infrastructure was successfully forecasted. This predictive lens ensured that protections were not siloed to a single brand but extended to protect end-users across the entire Indonesian financial ecosystem from cascading fraud attempts.

- Phishing Infrastructure Mapping: The identification of specific web design patterns within the threat actor’s generation framework facilitated the prediction of future attack distribution points. The early identification of these domains enabled the implementation of customized detection and prevention solutions, ensuring that clients remained protected before the malicious domains were actively circulated to the public.

Conclusion

The emergence of the fraud campaign involving fake Coretax apps in Indonesia serves as a critical case study in the evolution of mobile banking trojans and brand abuse. It demonstrates that contemporary threat actors no longer operate in silos; instead, they utilize industrialized malware-as-a-service (MaaS) frameworks to target entire national ecosystems simultaneously. The transition from simple credential harvesting to full remote device control — orchestrated through combined vishing and malware execution — signals a heightened level of operational maturity.

Threats such as Coretax demonstrate that modern fraud and malware operations can no longer be addressed through isolated security controls or basic multi-layered defense. Mobile banking trojans are not only technical threats — they represent a fusion of cybercrime, social engineering, brand impersonation, and financial fraud execution.

To combat this, a unification of Threat & Fraud Intelligence, Digital Risk Protection, Device Intelligence & Behavioral Biometrics such as Group-IB’s Cyber Fraud Fusion approach is essential to connect the full attack chain into a single operational picture.

Ultimately, the findings of this analysis confirm that detection is a necessity, but prediction is the differentiator. The ability to forecast brand abuse cycles and map malicious infrastructure before the execution phase might be the only viable method for minimizing systemic loss. To maintain trust in Indonesia’s digital transformation, institutional stakeholders must prioritize the adoption of collaborative intelligence platforms and runtime protection technologies. By doing so, the “trust equity” of national services can be preserved, and the digital ecosystem can be fortified against the inevitable evolution of cross-border cyber fraud.

Recommendations

For businesses and organizations:

- Deploy a real-time brand protection service with AI-driven detection and automated enforcement mechanisms that can effectively dismantle fraudulent infrastructure before it reaches scale, such as Group-IB’s Digital Risk Protection platform.

- Proactively monitor third-party app stores, social media platforms, and domain registries.

- Establish automated takedown workflows to minimize the dwell time of fraudulent applications and “typosquatted” domains.

- Adopt a behavioral biometrics and risk-based profile analysis solution such as Group-IB’s Fraud Protection platform to augment traditional credential verification systems.

- Non-phishable indicators such as keystroke dynamics and device telemetry enable more accurate identification of anomalies that deviate from a legitimate user’s baseline profile against a fraudster or bot.

- Share intelligence and best practices with peers and regulators to stay ahead of emerging fraud trends.

For consumers:

- Access government and national public services only through official channels – websites, apps, or verified customer service numbers – where applicable.

- Always confirm the origin of messages, texts or email even if they look official. When in doubt, do not click on links within these messages.

- Always double-check URLs before entering personal or banking data.

- Set limits and notifications for bank transactions. Many banking applications provide some level of self-imposed restrictions. This can prevent or delay greater financial loss in the event an account is compromised.

- Proactively report suspected fraudulent URLs, messages or apps to the relevant authorities and organizations.

For policymakers and regulators:

- Support public awareness campaigns that emphasize risks of installing applications from unofficial sources, especially for key public infrastructure, government and financial service sectors.

- Improve early threat prediction capabilities and proactive blocking before loss occurs by deploying a national collaborative cyber fraud intelligence framework such as the Group-IB Cyber Fraud Intelligence Platform (CFIP) that enables secure sharing of risk signals and suspicious data between participating organizations such as financial institutions without exposing PII through patented GDPR-compliant tokenization.

Acknowledgment of research support:

Pavel Naumov, Senior Security Researcher FPBryan Karunachandra, Fraud AnalystNikita Rostovtsev, Technical HeadVladimir Timofeev, Cyber Intelligence ResearcherVladimir Kalugin, Operational DirectorJia Hwei Soh, Head of the High-Tech Crime Investigation DepartmentJomphat Itsarawisut, Cyber Investigation Specialist

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS)?

Malware-as-a-Service, or MaaS, is a “subscription-based” cybercrime business model in which malware creators lease or sell pre-built and customisable malicious tools to other threat actors. This allows for rapid scaling of malware attacks across different geographies and industries with minimal overhead. MaaS is similar and related to RaaS (Ransomware-as-a-Service), which you can read more about in the Group-IB Knowledge Hub.

What is a RAT (Remote Access Trojan)?

A remote access trojan, or RAT, is a type of malware that grants unauthorized remote access to a target’s device, giving attackers control of compromised devices or systems undetected. RATs can enable various malicious activities, such as monitoring user behavior, extracting sensitive information, and deploying additional malware. The two malware families reported in this blog, Gigabud.RAT and MMRat belong to this group. Read more about RATs in the Group-IB Knowledge Hub.

What is “vishing” and how is it different from phishing or smishing?

Vishing is short for voice phishing, a social engineering attack in which cybercriminals use phone calls or voice messages to trick individuals into sharing sensitive personal information, such as bank account information, credit card numbers, social security numbers, or login credentials, often impersonating trusted official parties. Read more about vishing, phishing, and smishing (sms and text phishing) in the Group-IB Knowledge Hub.

What are the tactics used by fraudsters in the Coretax campaign?

- Exploiting Indonesia’s annual tax return season.

- Obtaining victim’s personally identifiable information (PII).

- Impersonating Indonesian Tax Authority officers (DJP) through vishing.

- Use of phishing links and malicious applications disguised as the official Indonesian tax payment platform, Coretax, to harvest sensitive financial data and establish remote device control.

- Remote access tools enable full victim device and account takeover.

Is the Coretax campaign contained to a single event or industry?

Group-IB investigation suggests that the same MaaS infrastructure used in the Coretax campaign has also been used to impersonate more than 16 other brands and services in Indonesia, as well as as a wider regional reach with the identification of up to 996 phishing URLs targeting Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and South Africa.

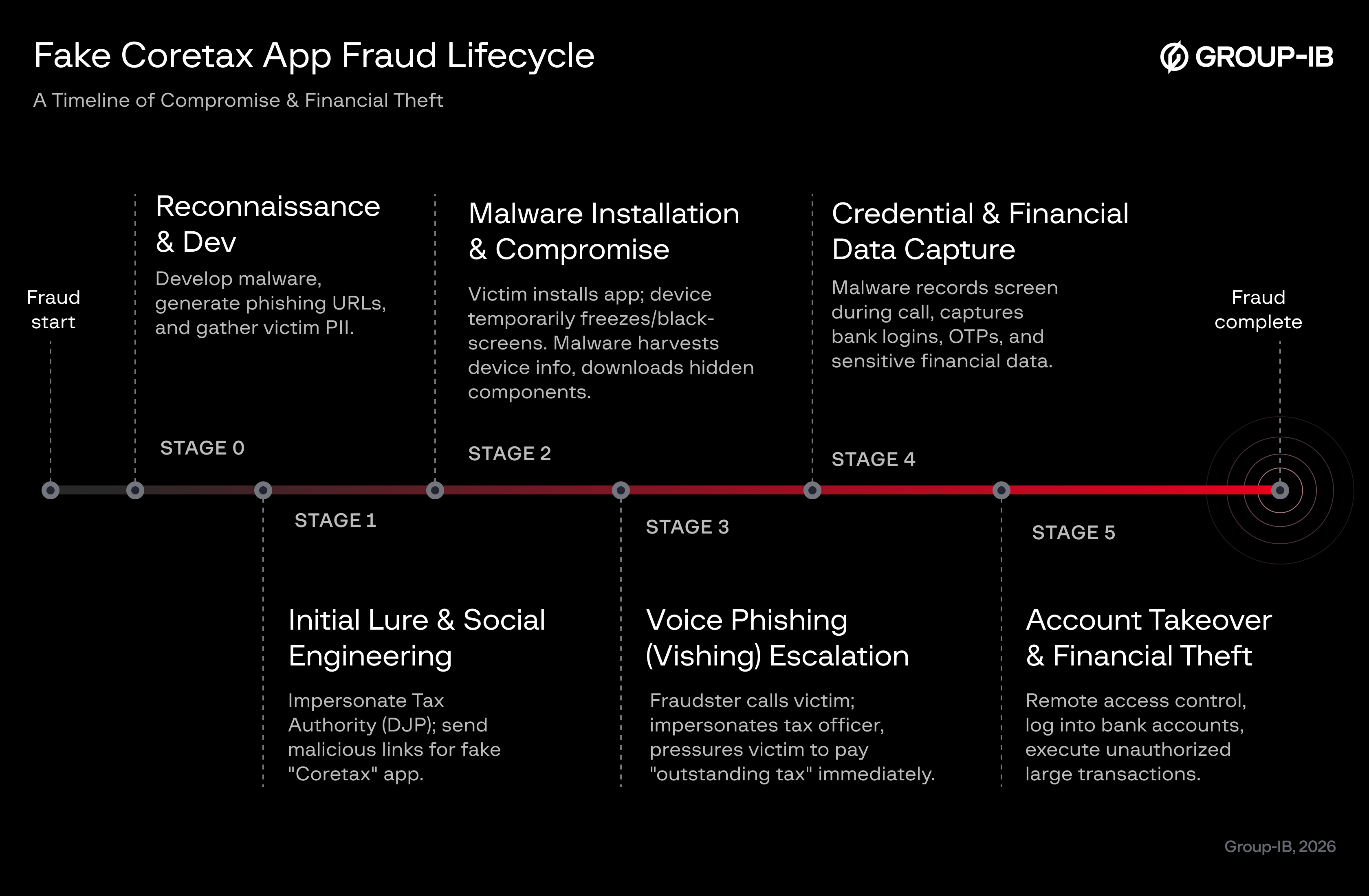

Group-IB Fraud Matrix

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

File Indicators

Over 200 Group-1 Gigabud.RAT Coretax samples were identified. This is a partial list. Group-IB customers can access our Fraud Intelligence Portal for the full list.

| Application Name | sha1 |

| CORETAX | 004d80e0efe9ea4d572350e8ce4771dfa432f0a2 |

| CORETAX | 00fcb2abd35049ad3cc9a8a3e1aaba156c0770cf |

| CORETAX | 02462bace6937e92f3d1ef35f08c4ad270082104 |

| CORETAX | 036aa79692470ad8d6a3bedb5da310af111317af |

| CORETAX | 03a1bcd3ba59c02ce6c37699baa73a2c075a6644 |

| CORETAX | 041dcd27e1c77548f7d5897b43a6e1817cb3e9d0 |

| CORETAX | 045144bfd86e0cf8d884ec4668d074a8d6eb4ee1 |

| CORETAX | 047190859b100d017c3b651f488eef8eba98ad28 |

| CORETAX | 07701239a7003699a02aa97bfab46e7b92800949 |

| CORETAX | 0852fbee4372c194f429b8ec217a5699f56448dc |

Group-2 MMRat Coretax samples:

| Application Name | sha1 |

| Coretax | 3f018345d993d0d8fd778c7f6f4667cc0e974dd4 |

| Coretax | 49acba8d46b57fdd324f32735e0052750f51b844 |

| Coretax | 6f474c2d89850f907f538921fd25bd52f0f99af0 |

| Coretax | 7b5c154e4aaa51b3652dc685c2f21b6eb70c1440 |

| Coretax | b125aea155d1d14be40644ba50f31418c3f40ebc |

| Coretax | ea87642a88788469e7aafc4657588b39709f1509 |

Group-3 Taotie Coretax samples:

| Application Name | sha1 |

| Coretax | fd09c9c916436e13da1c204f1f4c276c159f198a |

| Coretax | 2a954c7c1d764493abc285c34e47525c211fe768 |

| Coretax | 4bb5c9382fe37012017c88c6ac90afa2efeb2cbc |

| Coretax | 3bb475b9de75a5f1c6a941210b88b0c0f55f7005 |

| Coretax | 3106aa0c8b260e36ece48b8a681353de76d69ca9 |

| Coretax | 4911144aea43d00f6c7150766e4c0ab29c93d06e |

| Coretax | 9aab26a308f86ca137e6d6c171568a442e38abb6 |

| Coretax | f6627863f81cac5bf01664232473da47146f9d4c |

| Coretax | 075d8eeb5552da8524eb14a6ed72416e6e956aa3 |

| Coretax | c74dbe25d81bbe3c5e6177049ee393f6657fb799 |

| Coretax | cf9b8f3f1f795c3bdf0c14af66904ce8e2b95fff |

Network Indicators

Domains distributing malicious fake Coretax apps:

coretax-pajak[.]online coretax-pajakonline[.]com coretax-peralihan[.]com coretax-registrasi[.]com coretax-sinkronisasi[.]com coretax.skjgo[.]com coretax.svzgo[.]cc coretax.vfbgo[.]com coretaxlayanan[.]com coretaxonline-pajak[.]com coretaxpelayan[.]com coretaxpelayananonline[.]com coretaxperalihan[.]com djp.otuind[.]cc newsss[.]cc newsss[.]net ngovsss[.]com onlinecoretaxpelayanan[.]com pajak.abbgo[.]cc pajak.abfigo[.]cc pajak.crxind[.]com pajak.dkhid[.]cc pajak.jvcid[.]com pajak.ksjvgo[.]cc pajak.mghgo[.]cc pajak.mvzgo[.]cc pajak.mzfgo[.]cc pajak.nbvgo[.]com pajak.nsbid[.]com pajak.oeixgo[.]cc pajak.wpiego[.]cc pajak.yhvgo[.]com pajakcoretax[.]com pelayanan-coretax[.]com pelayananonlinecoretax[.]com pelayananonlinepajak[.]com pembaharuan-coretax[.]com peralihan-coretax[.]com peralihancoretax[.]com registrasi-coretax[.]com sinkronisasicoretax[.]com sss-cgov[.]com sss-gov[.]com sss-negov[.]com sss.aqego[.]cc sss.sksgo[.]cc sss.slhgo[.]cc sss.sligo[.]cc sssnegov[.]com verifikasi-coretax[.]com verifikasicoretax[.]online verifikasicoretaxonline[.]com

996 additional phishing URLs generated by the same threat actor have been confirmed. This is a partial list. Group-IB customers can access our Fraud Intelligence Portal to view the full list:

| Domains | Page IP |

| djp.dvhid[.]cc | 172[.]67.175.60 |

| sso-tha[.]com | 172[.]67.221.239 |

| djp.dvhid[.]cc | 104[.]21.31.66 |

| taspen.xufgo[.]com | 172[.]67.172.152 |

| sso-tha[.]net | 172[.]67.171.82 |

| 137.220.194[.]7 | 137[.]220.194.7 |

| sss-negov[.]com | 172[.]67.221.248 |

DISCLAIMER: All technical information, including malware analysis, indicators of compromise and infrastructure details provided in this publication, is shared solely for defensive cybersecurity and research purposes. Group-IB does not endorse or permit any unauthorized or offensive use of the information contained herein. The data and conclusions represent Group-IB’s analytical assessment based on available evidence and are intended to help organizations detect, prevent, and respond to cyber threats.

Group-IB expressly disclaims liability for any misuse of the information provided. Organizations and readers are encouraged to apply this intelligence responsibly and in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.

This blog may reference legitimate third-party services such as WhatsApp and others, solely to illustrate cases where threat actors have abused or misused these platforms.

This material is provided for informational purposes, prepared by Group-IB as part of its own analytical investigation, and reflects recently identified threat activity.

All trademarks referenced herein are the property of their respective owners and are used solely for informational purposes, without any implication of affiliation or sponsorship.