Introduction

Kernel-level malware, which operates in Windows’ ring 0, remains one of the most potent tools for cybercriminals. With access to the core of the operating system, attackers can disable defenses, maintain persistence, and remain hidden. Despite Microsoft’s evolving security mechanisms, attackers continue to adapt, leveraging signed drivers and underground services to bypass these protections.

This blog delves into how attackers leverage Windows kernel loaders and abuse digitally signed drivers to gain privileged access, disable security tools, and stealthily maintain control—bypassing traditional defenses and enabling advanced threat operations.

A more in-depth research report with expanded technical details and analysis will be published soon.

Key Takeaways

- Kernel-level attacks remain highly attractive to threat actors despite Microsoft’s improved defenses, due to the highest level of privileges on the compromised system and control they offer to attackers.

- The scale of malicious activity involving signed kernel drivers is growing: Since 2020, more than 620 drivers, 80+ certificates, and 60+ Windows Hardware Compatibility Program (WHCP) accounts have been associated with threat actor campaigns.

- Dark web services simplify access: Group-IB’s research uncovered underground market platforms that facilitate the creation and distribution of certificates, lowering the barrier to entry for threat actors seeking to deploy signed kernel-level malware.

- Stronger validation mechanisms by Certificate Authorities are essential when issuing Extended Validation (EV) certificates. Mitigating abuse of this process may require stricter controls, including thorough verification procedures, such as physical presence checks, to ensure the legitimacy of individuals and organizations and preserve the trust associated with EV certificates.

Windows Kernel: A High-Value Target

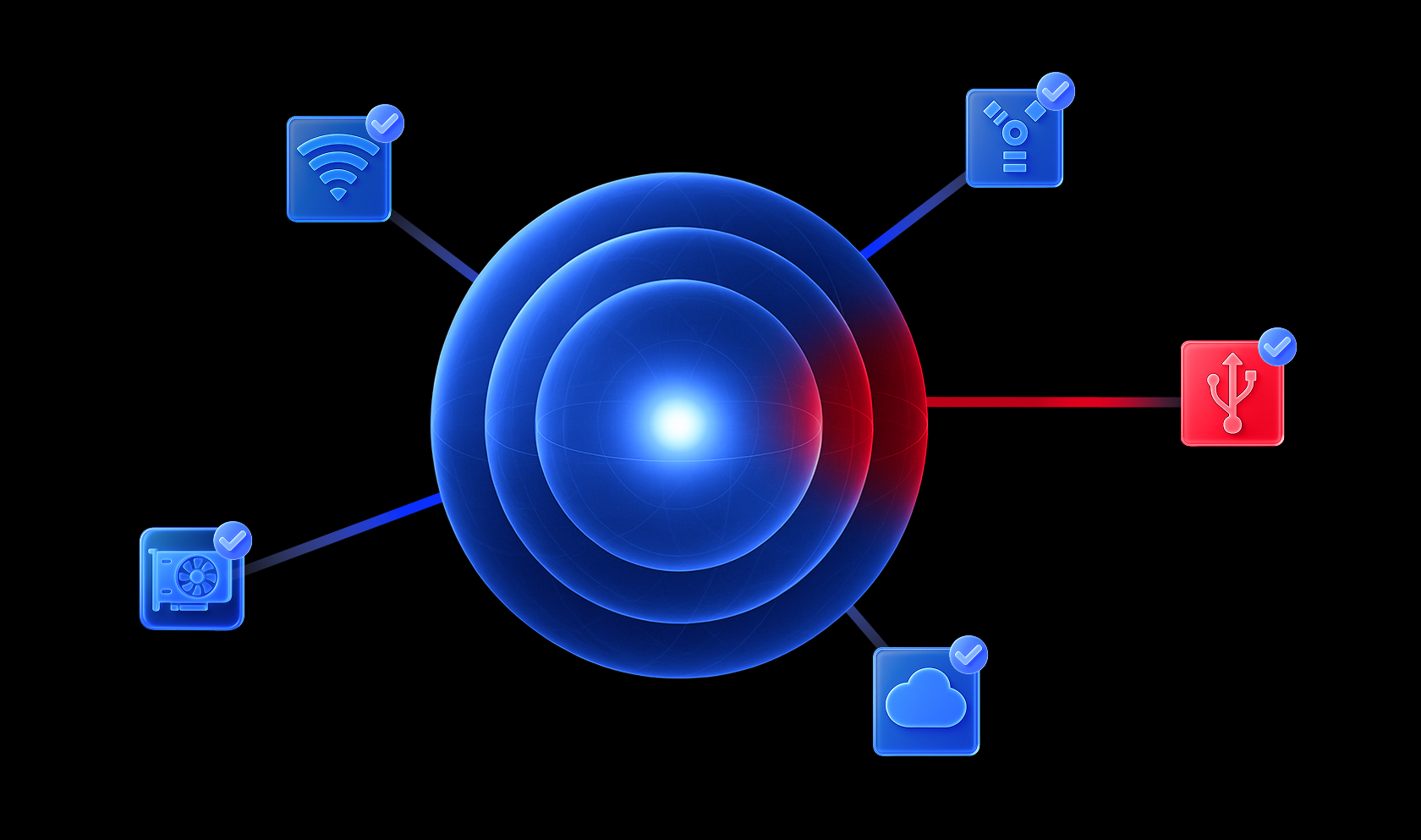

The Windows Kernel manages critical Operating System (OS) functions like memory, threads, and hardware input/output operations. Because third-party kernel drivers run at this level, they provide an ideal foothold for attackers to:

- Bypass antivirus and endpoint protection.

- Maintain stealth and persistence.

- Modify system behavior without detection.

To enhance system security, Microsoft introduced several countermeasures such as:

- PatchGuard: Prevents kernel patching.

- Driver Signature Enforcement (DSE): Ensures that only digitally signed drivers can run.

- Early Launch Anti-Malware (ELAM): Allow security software to load before other drivers during the boot process.

- Hypervisor-Protected Code Integrity (HVCI): Uses virtualization to enforce that only trusted signed kernel-mode code can execute, providing strong protection against kernel-level exploits.

Despite these protections, attackers have found ways around these mechanisms, mainly through abuse of digitally signed drivers.

Kernel Loaders: A New Layer of Obfuscation

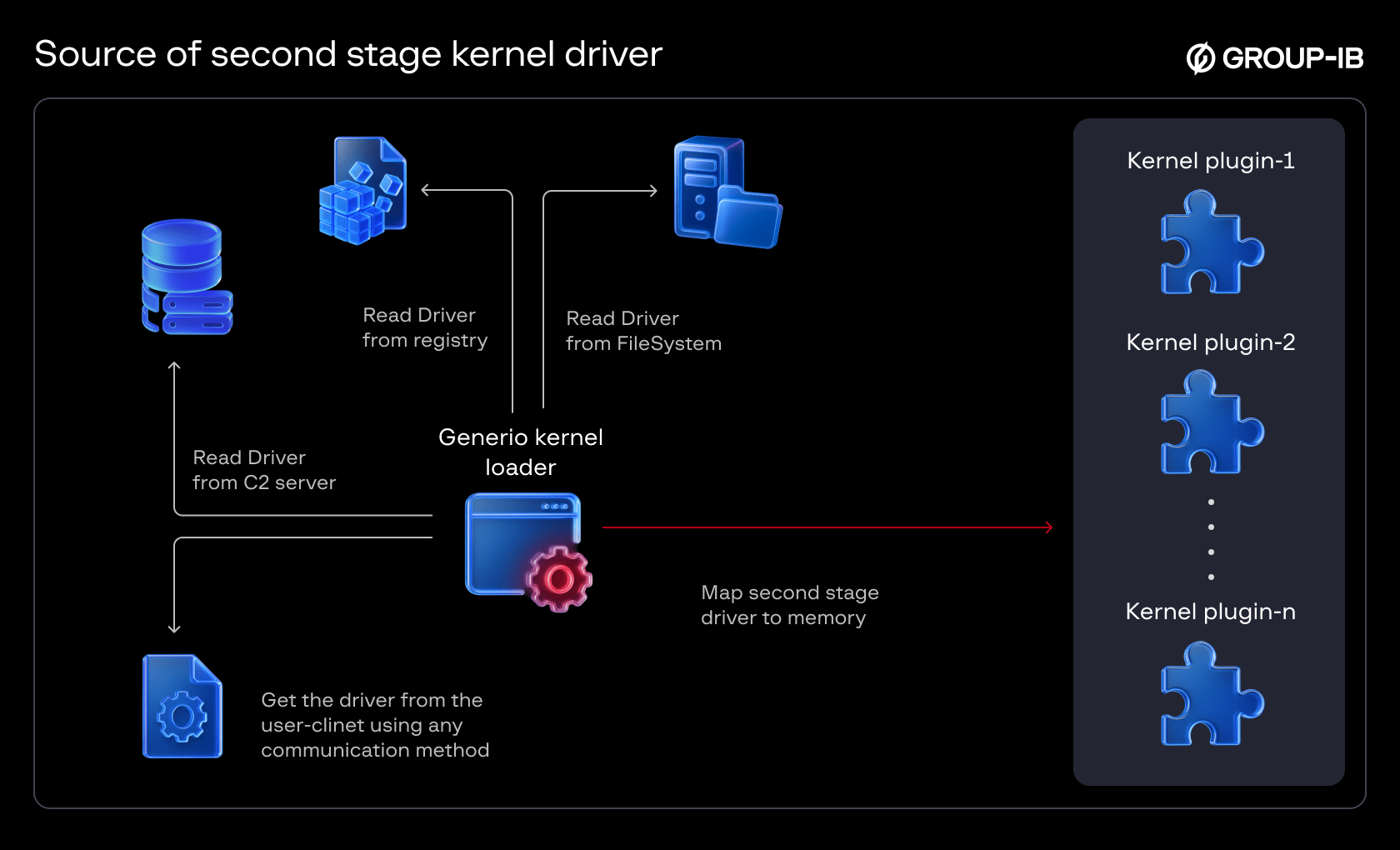

Kernel loaders are first-stage drivers designed to load secondary drivers, which can be:

- Unsigned drivers, loaded using reflective techniques.

- Signed drivers, officially installed as second-stage components.

This capability gives attackers powerful benefits: stealth, flexibility, and adaptability. It also enables their operations to continue undetected and allows the attacker to change his technique and adjust his driver seamlessly by compiling and loading the drivers into memory.

Group-IB’s threat intelligence investigation of over 600 signed malicious drivers from 2020 to first quarter of 2025, revealed that about 32% functioned as loaders, often retrieving payloads from command-and-control (C2) servers or storing them in the registry or local disk.

Figure 1: Source of Second Stage Kernel driver

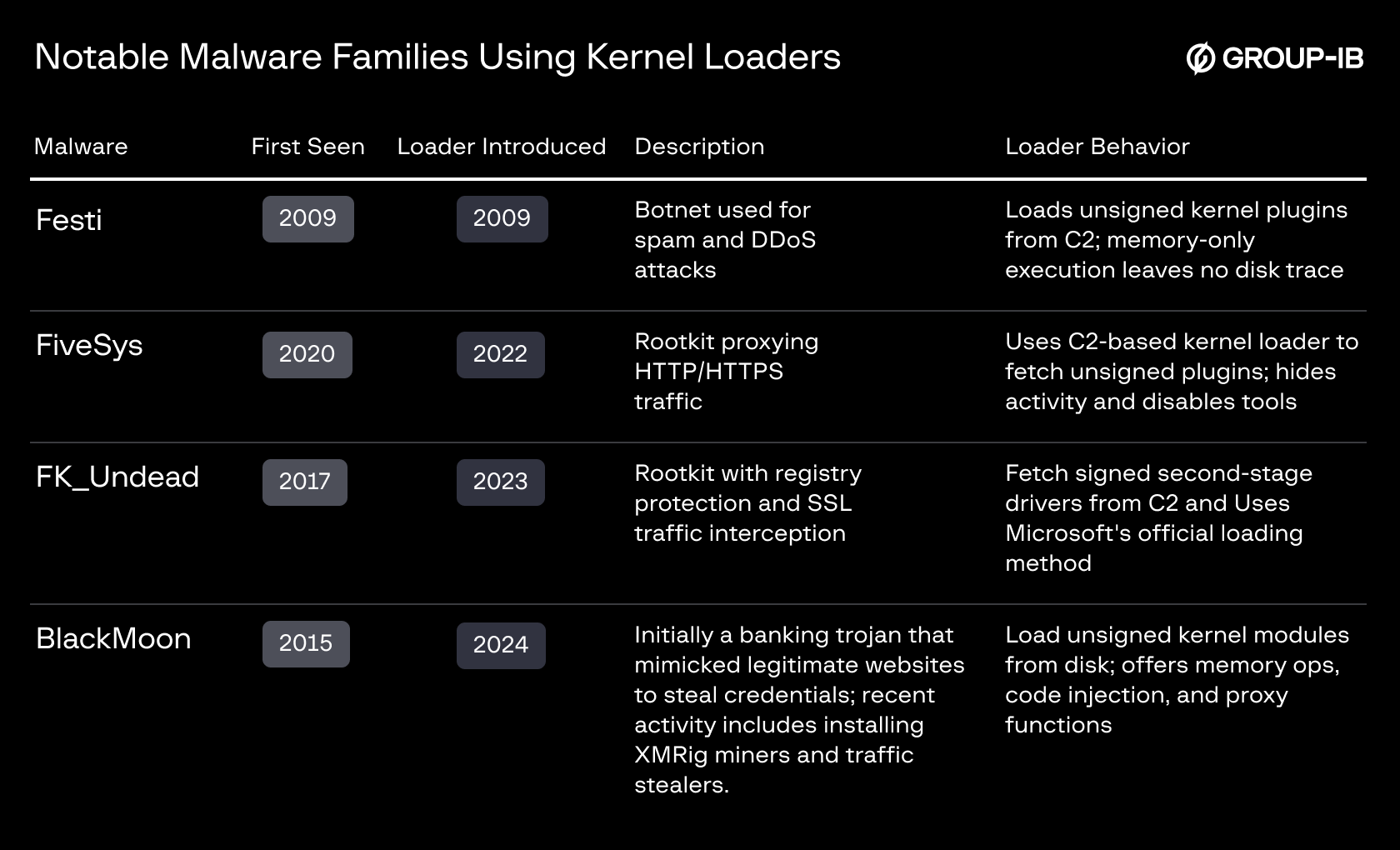

Table 1 : Notable Malware Families Using Kernel Loaders

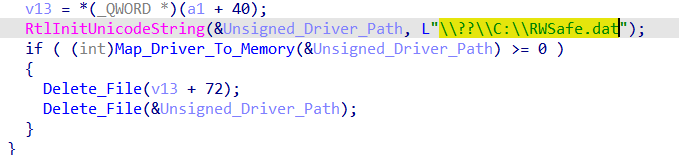

A Case of Signed Loader Abuse: Blackmoon and the Hugo Driver

Originally a banking trojan, Blackmoon evolved into a broader threat using the Hugo driver, a signed kernel loader that:

- Decrypts and loads unsigned drivers from hardcoded paths “C:\DriverModuleYuGuo.dat”.

- Acts as a proxy, executing memory injection, file access, and network tasks.

Figure 2 : Load Unsigned Driver from Hardcoded Path

The Rise of Signed Kernel Drivers and the Emergence of Underground Driver Certificate Providers

Since 2020, public intelligence reports have increasingly documented the use of signed kernel-level threats, which peaked in 2022. This surge was followed by a subsequent decrease, likely due to the security industry’s increased reporting of certificate and Windows Hardware Compatibility Program (WHCP) account abuse.

Specifically, in 2022 alone, over 250 drivers and approximately 34 certificates and WHCP accounts were identified as potentially compromised by security researchers.

As part of its ongoing research, the Group-IB threat intelligence team conducted a comprehensive analysis of kernel-level implants linked to various threat actor groups and malware families.

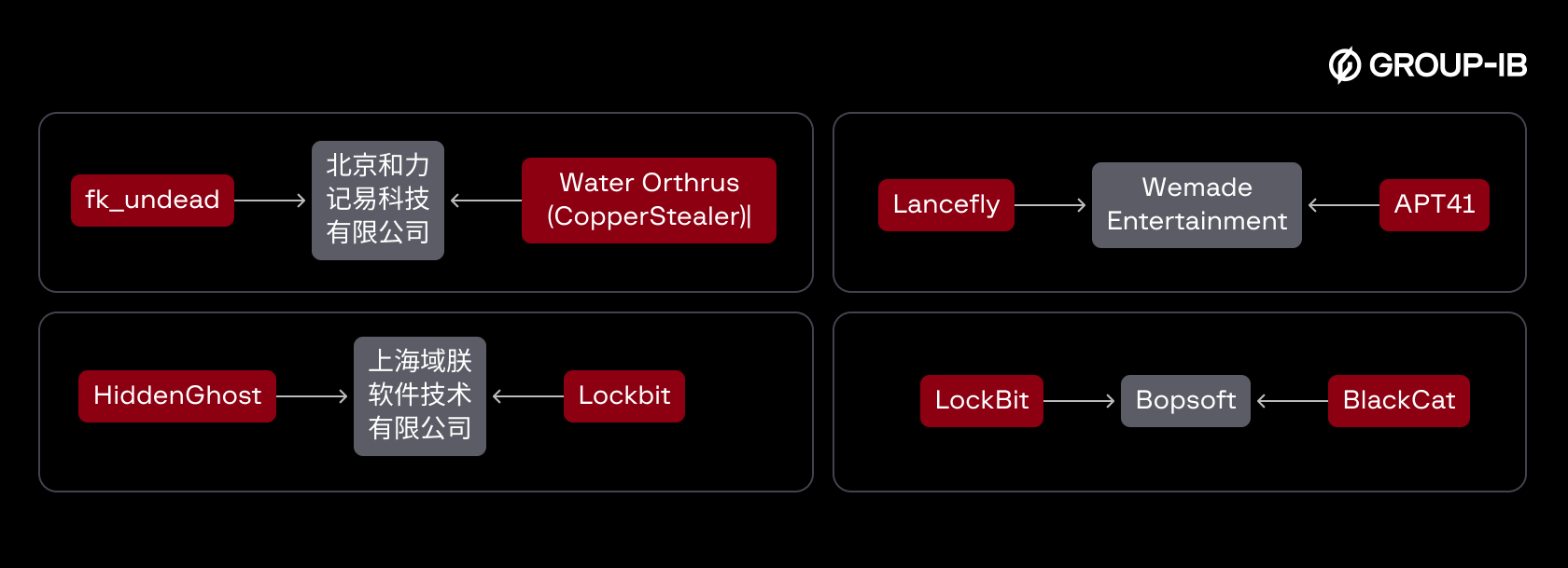

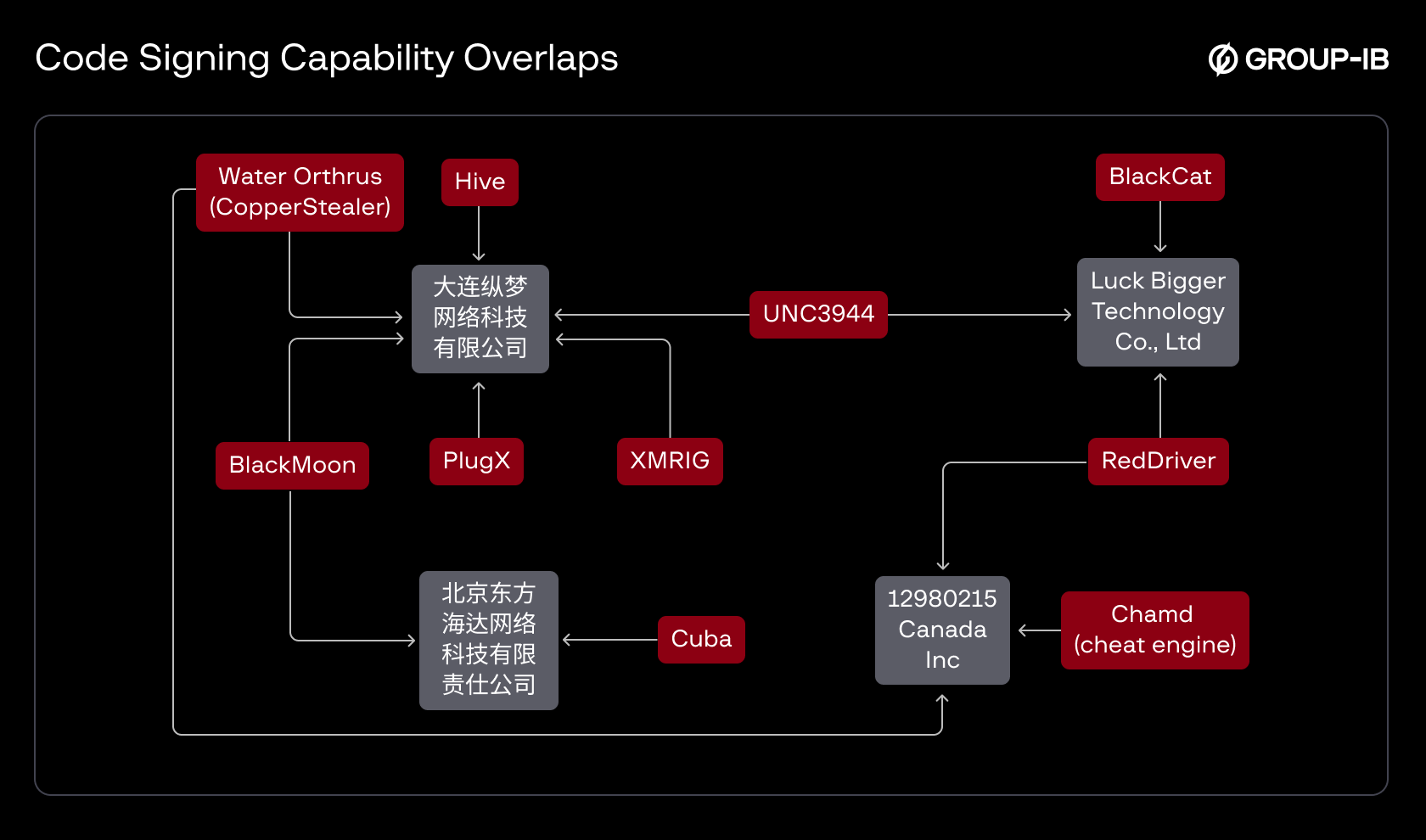

One of the most telling findings was the overlaps in certificates and Windows Hardware Compatibility Program (WHCP) accounts, used to sign drivers by seemingly unrelated threat actors and groups (Figure 3).

Group-IB found significant overlap in the signing infrastructure across different malware campaigns. For instance:

- POORTRY was used by Cuba, Hive, and LockBit ransomware.

- RedDriver was reused across campaigns for browser hijacking and persistence.

Figure 3: Code Signing Capability Overlaps Identified Among Different Threat Actors

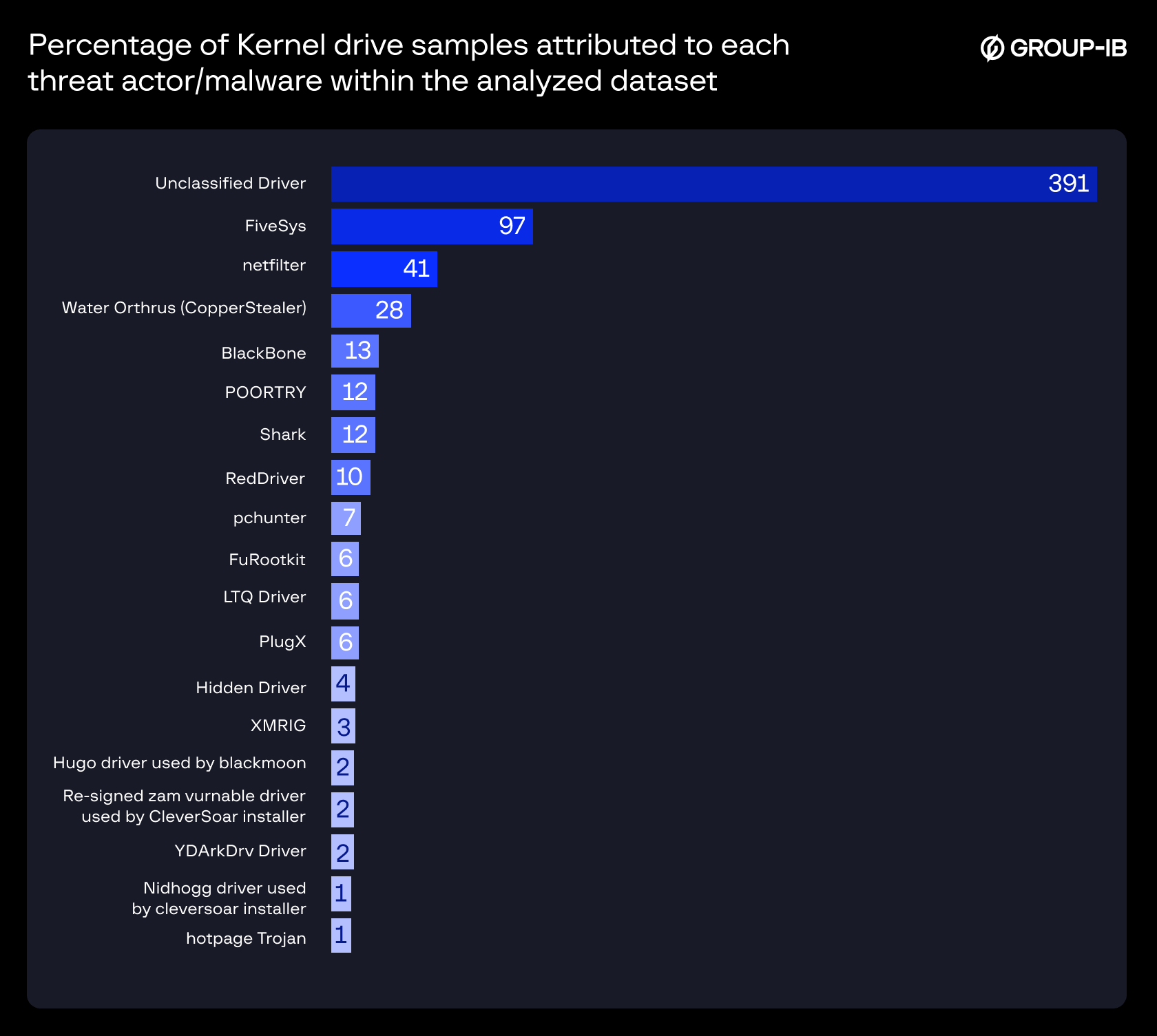

The chart below highlights the most prominent campaigns that favored this type of malware, determined by the number of signed variants identified. The largest share of signed kernel driver samples was linked to FiveSys, followed by Netfilter, CopperStealer, POORTRY, and RedDriver. Notably, more than 390 signed variants could not be conclusively attributed to any known threat actor, although they demonstrated malicious behavior. Figure 4 further illustrates the percentage distribution of these samples across each associated actor.

Figure 4: Percentage of Kernel Driver Samples Attributed to Each Threat Actor/Malware Within the Analyzed Dataset

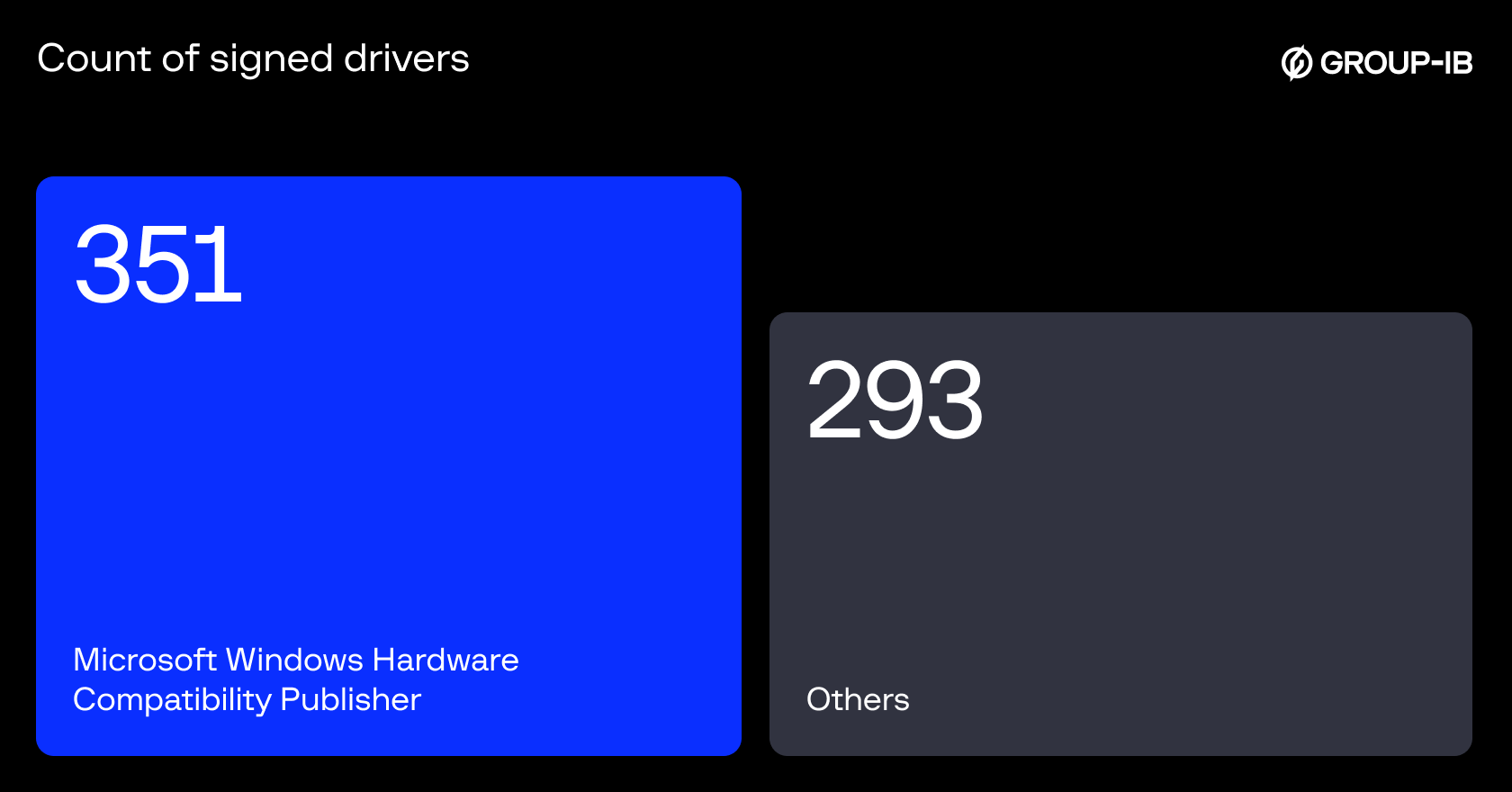

We classified all analyzed threats into two distinct categories based on how the malicious code was signed. The first category comprises signatures obtained via cross-signing certificates, while the second includes those signed through Microsoft’s Windows Hardware Compatibility Program (WHCP) portals. Notably, the WHCP method has become the more commonly used approach among cybercriminals since 2020.

Figure 5 : Count of Signed Drivers from 2020 – 2025 (first quarter)

Driver Signing Operations: Patterns and Geography

Our dataset and analysis of signed drivers indicate that multiple threat actors are responsible for the recent surge in maliciously signed kernel drivers. In the early stages, their efforts were focused on accumulating code-signing certificates and WHCP accounts.

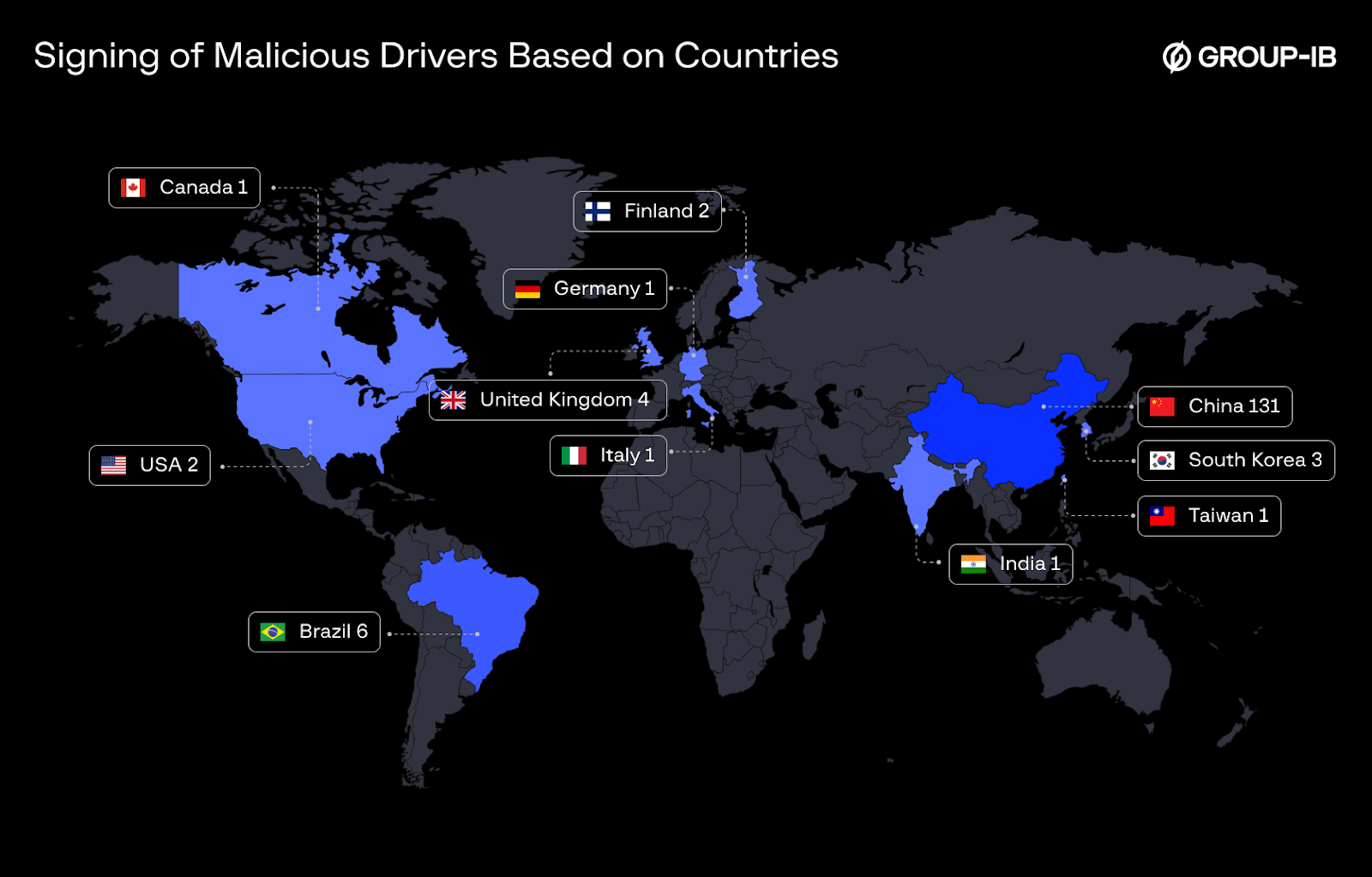

Operational activity ramped up around 2020, from 2020 to 2025, they had amassed a toolkit of over 80 certificates and credentials from over 60 WHCP accounts. These were used to sign over 600 malicious kernel drivers. Notably, most certificates and WHCP accounts are tied to Chinese companies, based on the company names and Chinese characters in the driver metadata (see Figure 6). Many of the certificates used were either:

- A stolen certificate for a known company.

- The Company was newly created after 2019 and has very little to no public information (we will see in the next section).

Figure 6 : Number of Companies Signing Malicious Drivers Based on Countries From 2020 Till first quarter of 2025

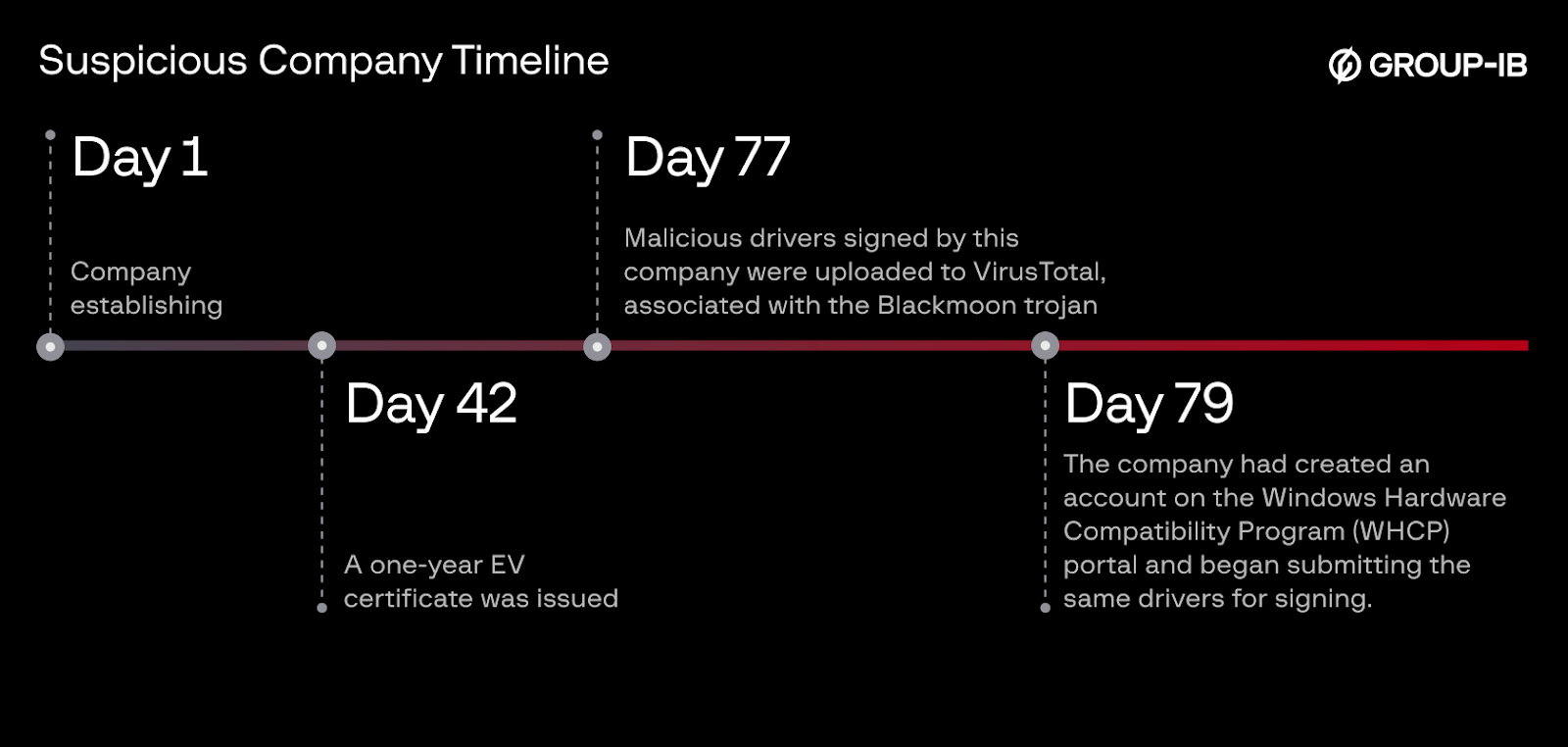

As an experiment, the Group-IB team investigated publicly available data associated with several companies whose certificates were used to sign drivers later identified as malicious, One of the organizations stood out during the research due to the complete absence of visible activity, from non-functional or inactive official websites to a lack of any public presence or mentions this company started signing malicious drivers within two months of its creation.

Figure 7 : Suspicious Company Timeline

How to submit a driver through WHCP? And Is It Hard to Get an EV Certificate?

After examining how signing certificates and WHCP accounts have been misused to sign malicious drivers, it’s important to understand how the legitimate process works — and where there may be opportunities for abuse.

According to Microsoft, any vendor wishing to sign a driver via the WHCP must follow these steps:

- Register for the Hardware Developer Program

- Enroll via the Microsoft Partner Center.

- Obtain an EV Code Signing Certificate

- Purchase from a trusted CA (e.g., DigiCert, GlobalSign).

- Install Required Tools

- Install the Windows Driver Kit (WDK) and Windows SDK.

- Optional: Use makecab, signtool, and inf2cat.

- Prepare the Driver Package

- Include: .sys (driver), .inf (setup), .cat (catalog), and optionally .pdb (symbols).

- Create a CAB File

- Use makecab to compress all files.

- Sign the CAB File

- Digitally sign it using your EV certificate via signtool.

- Submit for Attestation Signing

- Go to the Hardware Dev Center Dashboard.

- Select “Submit new driver” and upload the signed CAB.

- Fill in OS version, architecture, and other metadata.

- Wait for Microsoft Review

- Microsoft scans and signs the driver.

- Download the Signed Driver

- Once approved, retrieve it from the dashboard.

- Test the Driver

There are lots of steps that need to be taken to submit a driver for signing using the WHCP program, but the core requirements for driver signing are:

- Get an EV certificate

- Enroll at Microsoft Partner Center (MPC)

- A crash-free driver

- The driver passes Microsoft’s scanning checks

So, to be able to submit a driver, a legally registered company is a must — both to get an EV certificate and pass its verification process, and to register with Microsoft.

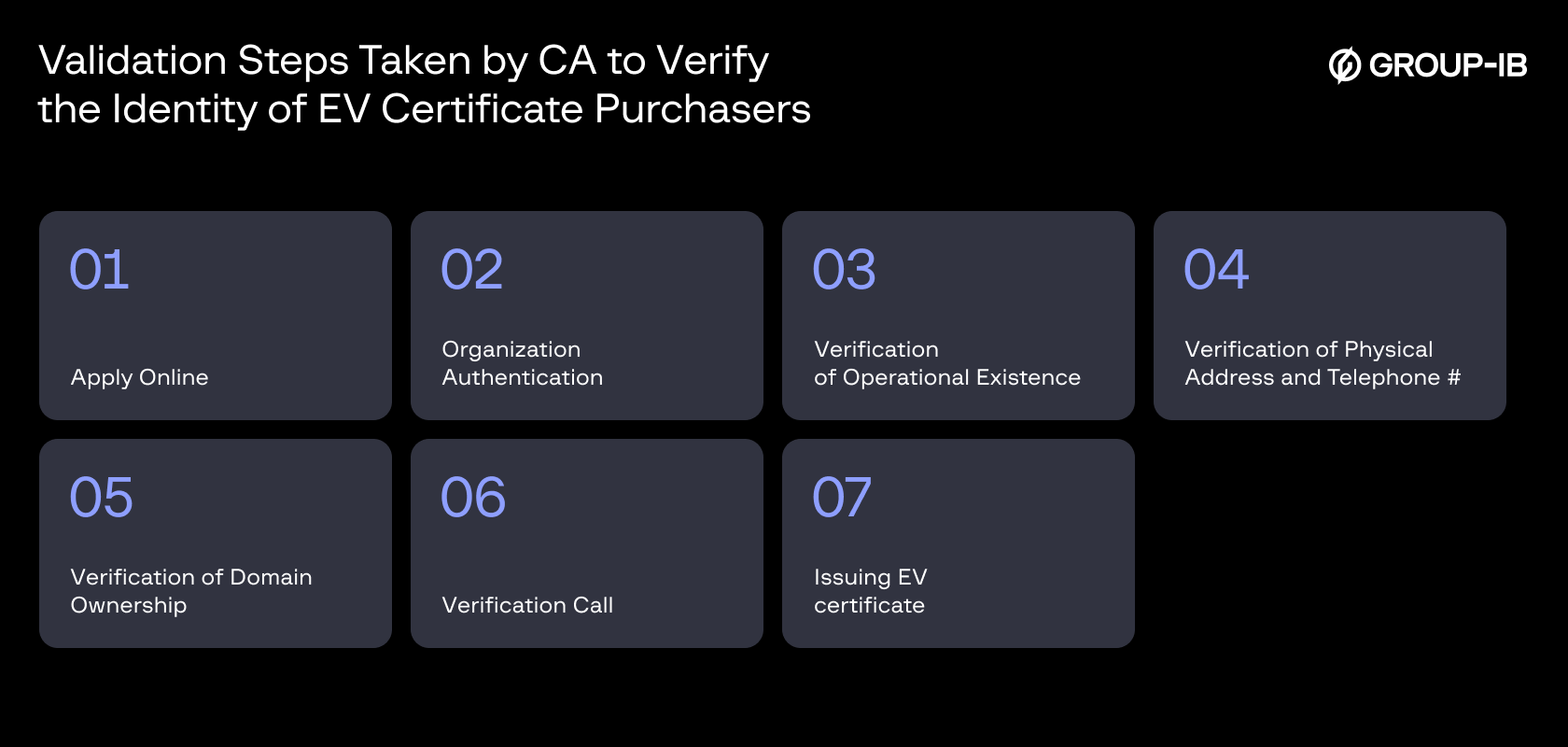

Below are the verification processes for a Certificate Authority (CA) needed to provide an EV certificate for companies:

- Legal Existence and Identity

- Verified via government registries

- Must match the exact legal name, registration number, and authority

- Operational Existence

- The company must be active for ≥3 years

- OR prove via:

- Bank confirmation letter

- Legal/accounting opinion letter

- Physical Address

- Verified using public records or business directories

- May require utility bills as proof

- Telephone Number Verification

- Must be listed publicly under the company name

- Domain Ownership

- Must prove control of the domain via DNS, WHOIS, or email validation

- Authorization for Certificate Request

- Requestor must be an authorized employee or representative

- May require ID, signed forms, or confirmation from a senior officer

- Human Involvement

- Manual verification is required:

- Validators review documents

- Conduct phone calls

- Confirm signatures

- Manual verification is required:

Figure 8 : Validation steps by CA

While this process may appear strict on paper, much of it is document-based and often relies on limited human interaction, primarily a phone call. For a legitimate business, the process is straightforward. However, well-resourced threat actors or nation-states may attempt to exploit these procedures by creating fake companies or using stolen credentials, particularly where there is limited human oversight.

One well-documented case example revealed a cybercrime group registering fake companies across the U.S. and U.K. to obtain EV certificates, which they later sold for prices ranging from $260 to $15,000 each.

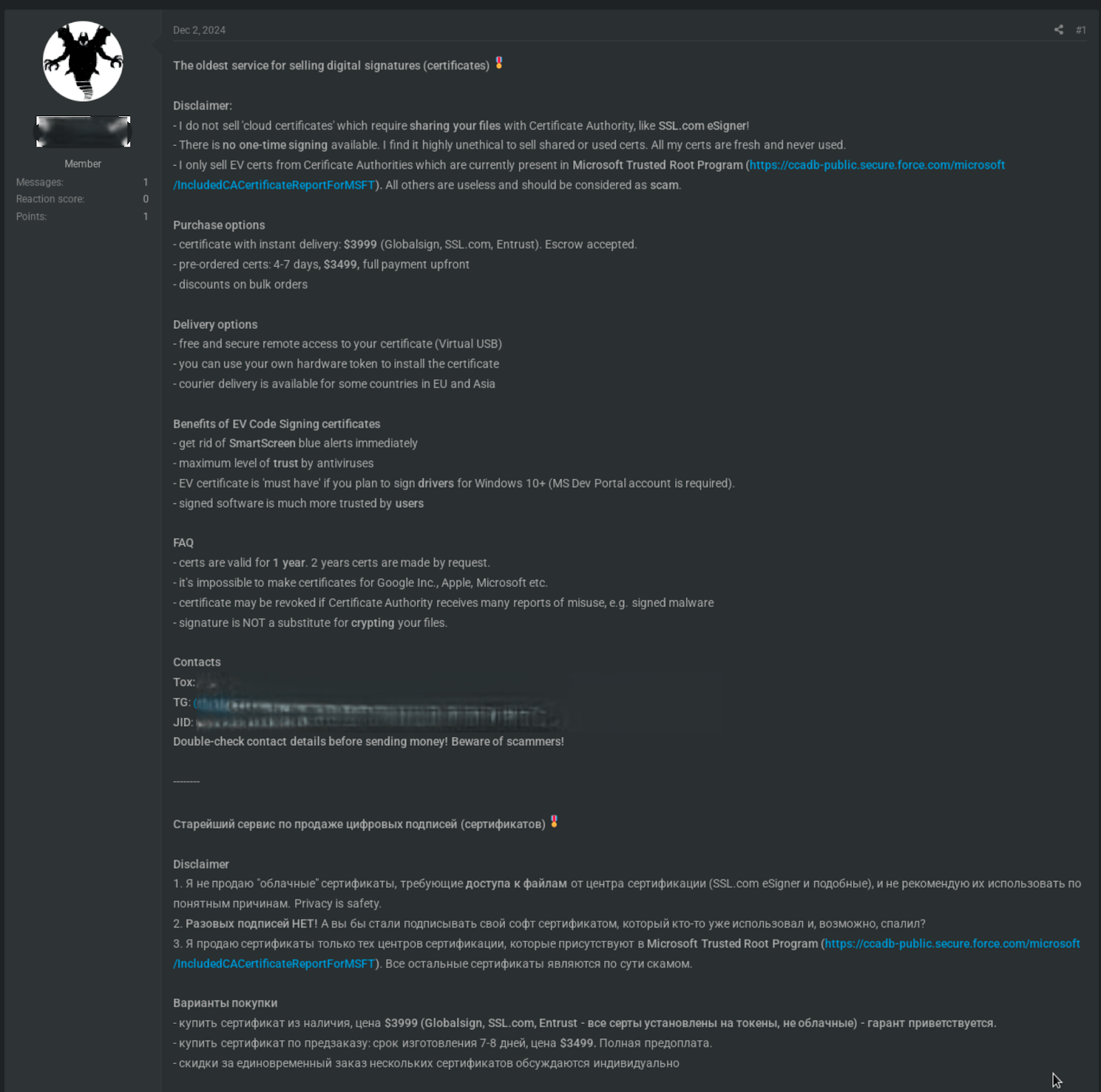

Dark Web Trade in Code Signing: Inside the Underground EV Certificate Market

This section explores the underground market for Extended Validation (EV) code-signing certificates, where multiple threat actors actively advertise and sell such services. Our investigation uncovered vendors, some of whom appear to be Russian-speaking actors operating within Chinese communities (RAMP), offering certificates to other threat actors. As of 2025, at least ten distinct sellers were identified.

These actors claim to provide EV certificates issued by certificate authorities (CAs) included in Microsoft’s Trusted Root Program, an essential requirement for submitting drivers through the WHCP. Many of these actors maintain a strong reputation on underground forums, evidenced by numerous positive reviews. The certificates are most likely obtained using either fraudulent business registrations (as mentioned in this paper) or stolen identities of real companies.

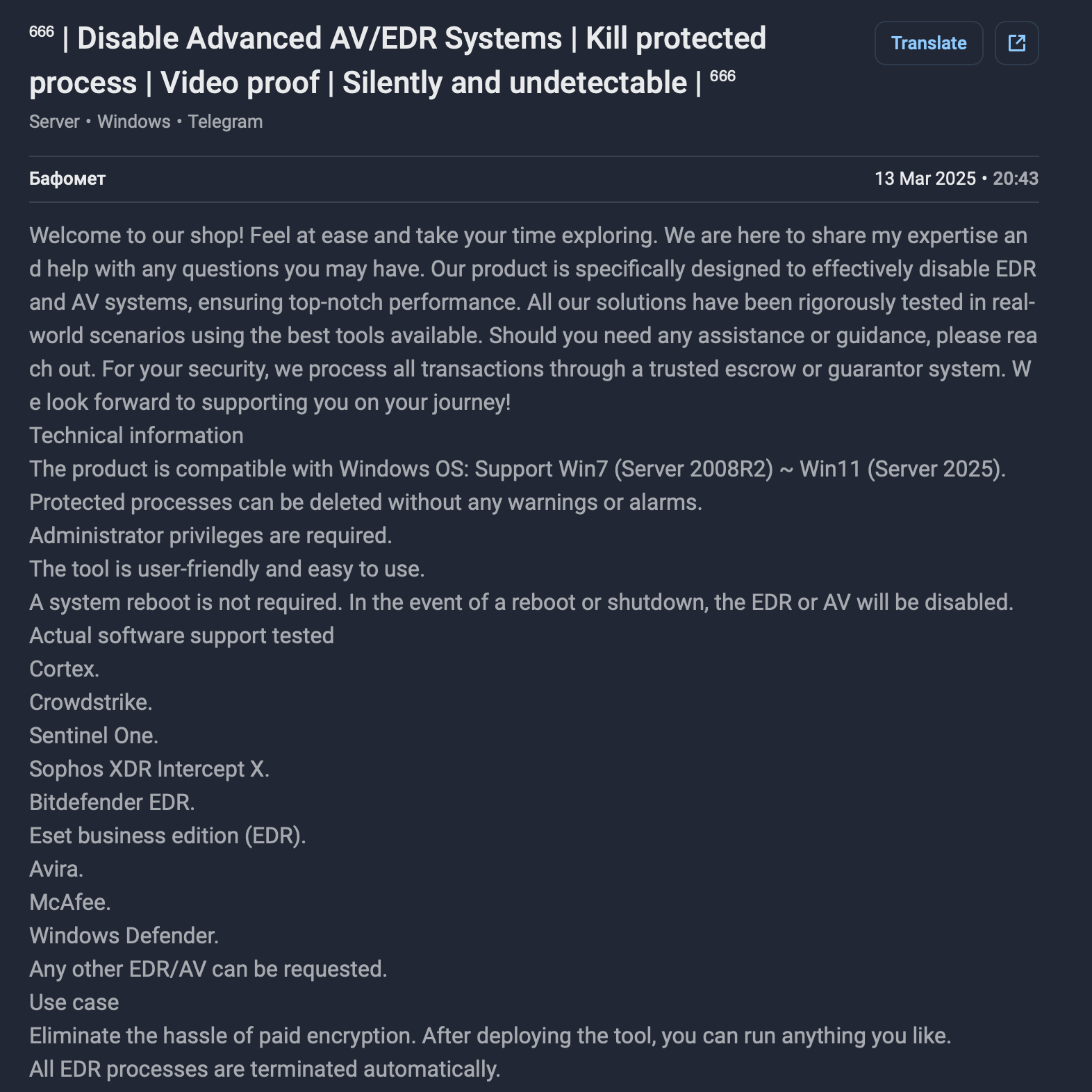

While in previous documented cases selling signing certificates for malicious drivers were mainly focused on EV certificates, in our dataset, the usage for WHCP accounts is increasing, and it is becoming more preferable by the Threat Actors to inherit more trust in the system. Several vendors we discovered offer WHQL-signed drivers intended to disable antivirus and EDR solutions.

Figure 9 : Selling EV certificates on an underground marketplace

Figure 9.1 : Signed AV Terminator driver

Conclusion and What Comes Next

The rise of Windows kernel loaders and the increasing use of signed drivers by threat actors underscore a sophisticated and growing threat to cybersecurity. Kernel loaders provide attackers with stealth, adaptability, and persistence by enabling the execution of second-stage drivers directly in memory, evading traditional detection methods.

Attackers leverage many signing certificates and WHCP accounts by exploiting legitimate processes like the WHCP and Extended Validation (EV) certificates. This includes those belonging to compromised or fraudulently registered organizations, signing malicious drivers, bypassing established security measures, and exploiting the trust model inherent in signed kernel drivers.

The emergence of the underground driver certificate providers highlights the resourcefulness of threat actors, enabling unrelated groups to deploy signed drivers for malicious operations such as disabling security tools, evading detection, and maintaining persistence. This trend complicates detection and reveals critical vulnerabilities in the driver-signing process, as well as the need for a stricter process.

To address these challenges, it is imperative to implement stricter oversight in certificate issuance and driver signing processes by adding more verification steps and a more human-oriented process based on physical meetings. Enhanced collaboration between certificate authorities, operating system vendors, and the security community is essential to proactively identify and revoke abused certificates.

Disclaimer:

This publication is intended solely for informational, educational, and research purposes. All technical findings, examples, and driver-related analyses described herein are based on data from Group-IB sources and/or publicly available materials.

Mentions of specific companies, certificate issuers, products, or developer accounts are provided exclusively to illustrate observed technical patterns, malware behavior, or threat actor tactics. These references do not imply any wrongdoing, negligence, intent, or deficiencies in security practices by the mentioned entities. Group-IB does not assert or infer any direct involvement of these organizations in malicious activity.

Any assessments, interpretations, or hypotheses regarding the abuse or misuse of driver signing mechanisms – including Extended Validation (EV) certificates or Windows Hardware Compatibility Program (WHCP) accounts – are grounded solely in technical analysis and available forensic evidence at the time of publication. Such hypotheses are based on available data and are not presented as verified or conclusive findings.

Descriptions of tools, techniques, or malware capabilities are shared solely to promote cybersecurity awareness, improve defensive measures, and advance industry understanding of evolving threats. This publication does not endorse, encourage, or facilitate any unauthorized, unethical, or illegal activity.

Group-IB makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, or currentness of the information provided, which may evolve with ongoing research. The content herein does not constitute legal, commercial, or security advice. Readers are solely responsible for ensuring compliance with all applicable laws, regulations, and contractual obligations in their respective jurisdictions.