Executive summary

Ransomware activity increased drastically over the past couple of years and became the face of cybercrime by 2021.

According to the “Ransomware Uncovered 2020-2021” report, the number of ransomware attacks increased by more than 150% in 2020. The attacks grew in not only number but also scale and sophistication — the average ransom demand increased by more than twofold and amounted to $170,000 in 2020. The norm is shifting toward the millions: the Colonial Pipeline allegedly paid USD 5 million to get its business back. The case propelled the question of ransomware to the top of the political agenda.

In the meantime, 2021 continues to prove that no company is immune to the ransomware plague. Ransomware operators are not concerned about the industry so long as the victim can pay the ransom. The prospect of quick profits motivates new players to join big game hunting. Ransomware operations show no signs of slowing down. The gangs evolve. They change their tactics, defense evasion techniques, and procedures to ensure that their illicit business thrives.

Given that ransomware attacks are conducted by humans, understanding the modus operandi and toolset used by attackers is essential for companies that want to avoid costly downtimes. Ultimately, knowing how ransomware gangs operate and being able to thwart their attacks is more cost-effective than paying ransoms.

One of the underlying trends of 2021 to keep in mind is the use of commodity malware. The infamous ransomware gang Ryuk, which is responsible for many high-profile cyber heists (including the attack on the Baltimore County Public Schools system) followed suit. The most recent addition to their arsenal, which is yet to be explored, is the malware called GrimAgent.

Our team did the first comprehensive analysis of the GrimAgent backdoor. It is intended mainly for reverse engineers, researchers and blue teams so that they can create and implement rules that help monitor this cyber threat closely. Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence team has created Yara and Suricata rules as well as mapped GrimAgent’s TTPs according to the MITRE ATT&CK® matrix.

Introduction

GrimAgent is a malware classified as a backdoor and that has been used as a prior stage to Ryuk ransomware. The ransomware family appeared in 2018 and was mistakenly linked to North Korea. Later on, it was attributed to two threat actors, FIN6 and Wizard Spider.

Given the limited knowledge about the links between Ryuk and GrimAgent, we decided to research GrimAgent samples discovered in the wild and show how GrimAgent is connected to Ryuk. The article analyzes the execution chain, TTPs, and the malware’s relevant characteristics.

The first known GrimAgent sample (SHA-256: 03ec9000b493c716e5aea4876a2fc5360c695b25d6f4cd24f60288c6a1c65ce5) was uploaded to VirusTotal on August 9, 2020 at 19:20:54. It is noteworthy that an embedded binary into the initial malware was employed and had a timestamp of 2020-07-26, the timestamp could have been altered but the dates coincide with our hypothesis about the new malware.

From a functionality point of view the malware is a backdoor, but it behaves like a bot. We analyzed a completely different custom network protocol where the infected computer would register on the server side and provide a reconnaissance string of the client, after which it would constantly make requests to the C&C server asking which are the next commands to be executed. During our research we performed several tests with the aim to get the next stage payload. We infected several testing devices with different settings, but did not manage to obtain any payloads. Based on our findings, it is likely that the actor implemented different defense and delivery mechanisms to protect the integrity of its systems and ensure that the operations are flawless — which is not uncommon and we have witnessed this in the past. This means that GrimAgent developers potentially implemented threat detection systems capable of detecting sandboxes or bot requests in order to protect themselves from things such as analysis, added filters based on geolocation and blacklists/whitelists. The extreme meticulousness shown by the actors behind the malware and their attention to detail when carrying out attacks is both relevant and remarkable.

According to Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence & Attribution system, Ryuk operators used different commodity malware over time (including Emotet, TrickBot, Bazar, Buer, and SilentNight) to deploy ransomware. However, the big blows suffered by Trickbot and Emotet could have prompted Ryuk operators to partner with GrimAgent. A detailed analysis of the latest TTPs used by various ransomware strains is available in the Ransomware Uncovered 2020/2021 report.

Welcome to the world of Threat Intelligence

Defeat threats efficiently and identify attackers proactively with a revolutionary cyber threat intelligence platform by Group-IB

Connections to Ryuk

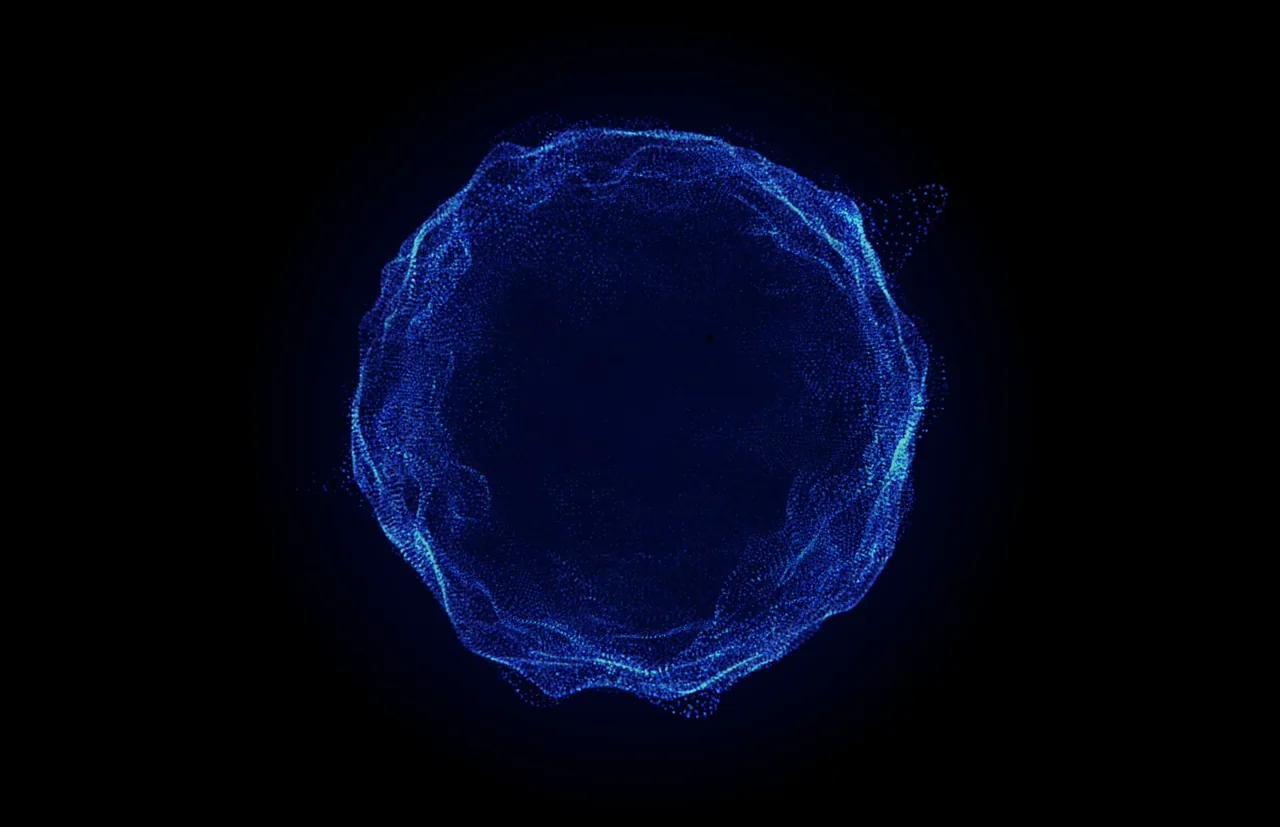

Analyzing the GrimAgent Command and Control domain revealed an interesting URL. When making a request on the domain, the Command and Control server returns a content designed for victims of the Ryuk ransomware, in addition to revealing its location on the TOR network.

Command and control landing page:

Fig. 1: C2 landing page

Command and control landing page source code:

< html > < body > < style > p:hover {

background: black;

color:white

} < /style> < p onclick = 'info()' style = 'font-weight:bold;font-size:127%;

top:0;left:0;border: 1px solid black;padding: 7px 29px;width:85px;' >

contact < /p>balance of shadow universe

< div style = 'font-size: 551%;font-weight:bold;width:51%;height:51%;overflow:auto;margin:auto;position:absolute;top:36%;left:41%;' > R

y

u

k < /div> < /body>