Introduction

Imagine you enter a bank with the intention of applying for a loan but your application gets rejected as the bank’s worker tells you that there has already been a loan taken out in your name and your credit limit has been maxed out. You have just found out that you’re a victim of credit fraud.

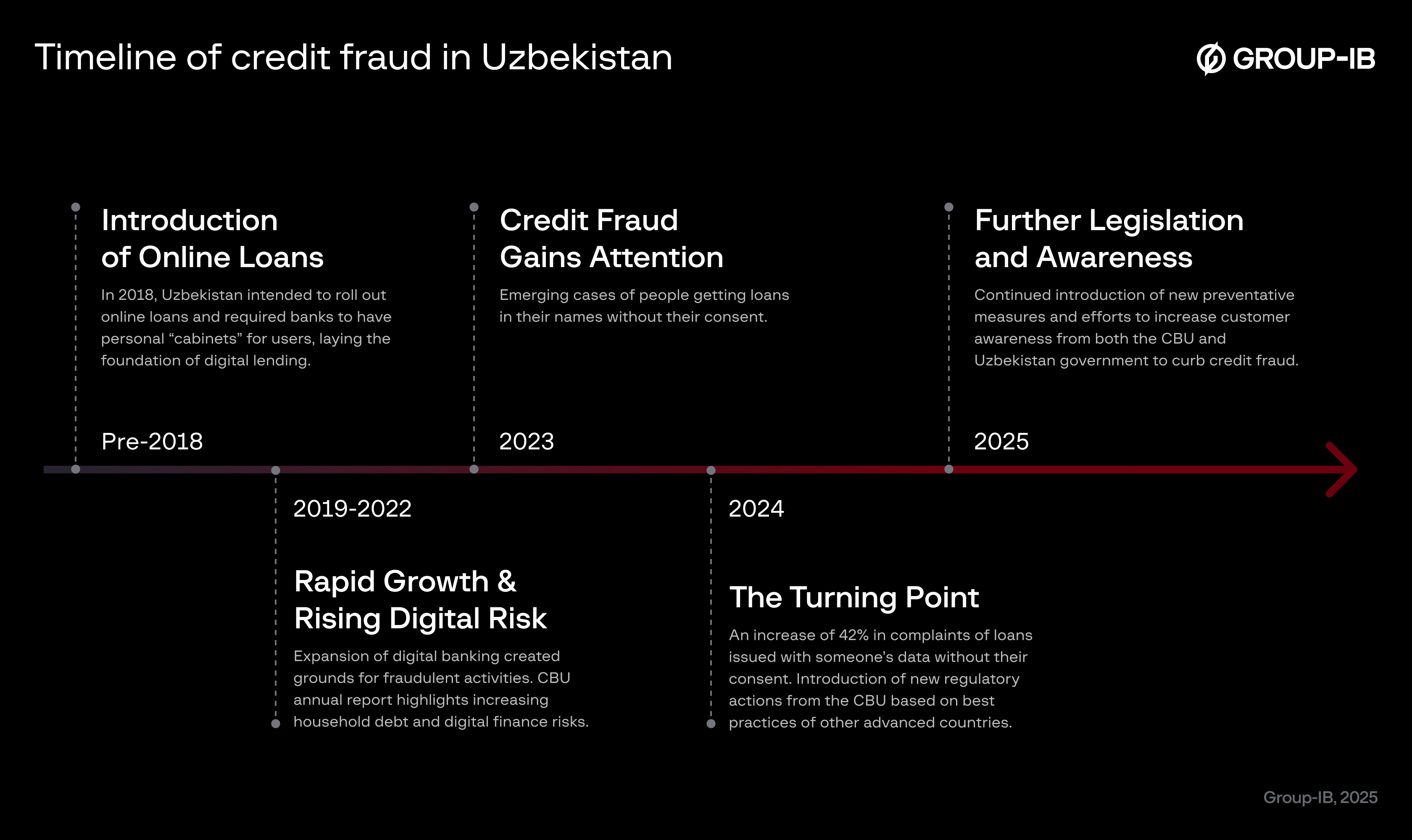

Online lending is rapidly gaining popularity in Uzbekistan, and with it, the number of credit fraud cases is also on the rise. According to data from the Central Bank of Uzbekistan (CBU), there were 463 reported cases of remote online loans issued in someone’s name via apps or a fake identity, resulting in financial losses totaling approximately 15 billion UZS in 2024 alone.

This report provides an overview of the current credit fraud landscape in Uzbekistan. It explores the key factors that enable such fraud to occur and outlines potential measures to prevent it.

Key discoveries

- Fraudulent loans issued in the names of Uzbek citizens have soared in recent years – a 42% increase in 2024 compared to 2023.

- Fraudsters often impersonate bank or central-bank employees and use social engineering (e.g., fake calls, malware) tactics to gain access to personal data or banking credentials

- 34% of credit fraud activities in Uzbekistan are associated with calls from a “bank worker” or “government official”.

- The Uzbekistan government has taken active initiatives for preventing credit fraud in the country, e.g., citizens can self-block any new loan applications being formalized on their name.

- According to new legislation from the president of Uzbekistan, victims of credit fraud can be exempted from payment obligations of fraudulent credits applied in their names.

Who may find this blog interesting:

- Cybersecurity analysts and corporate security teams

- Threat intelligence specialists

- Cyber investigators

- Law enforcement investigators

- Cyber police forces

Group-IB Fraud Intelligence Portal:

Group-IB customers can access our Fraud Intelligence portal for more information about the credit fraud scheme described in this blog.

Figure 1. Timeline of Credit Fraud in Uzbekistan

Analysis of common credit fraud scenarios in Uzbekistan

Credit fraud is a growing problem worldwide. Although specific details may vary, most fraud cases follow a similar pattern. Understanding this pattern can help individuals and organizations recognize and prevent these crimes.

In the majority of credit fraud cases observed in Uzbekistan, fraudsters take out “microcredits” in the name of the victim. This type of credit service has recently started to be offered by banks in Uzbekistan, creating intense competition where banks attempt to offer loans easier, faster, and cheaper. The whole process can be completed online in the case of many banks and only requires the clients to pass the verification and be logged into the bank’s application which is an ideal opportunity for fraudsters to take advantage of.

As the World Bank notes, fraud via “taking out credit fraudulently in someone else’s name” is a top risk in digital-finance expansion in the country.

In Uzbekistan, such credit fraud cases are most commonly categorized into two scenarios:

- Bank clients fall victim to fraud committed by actual bank employees acting on personal motives. There have been many reported cases where current or former bank workers, having access to clients’ personal details, apply for loans on behalf of the victims without their knowledge. These loans are not issued directly in the victims’ names but transferred to accounts of shell companies (LLCs) created by the fraudsters. As a result, victims usually discover the fraud only when loan payment due date arrives.

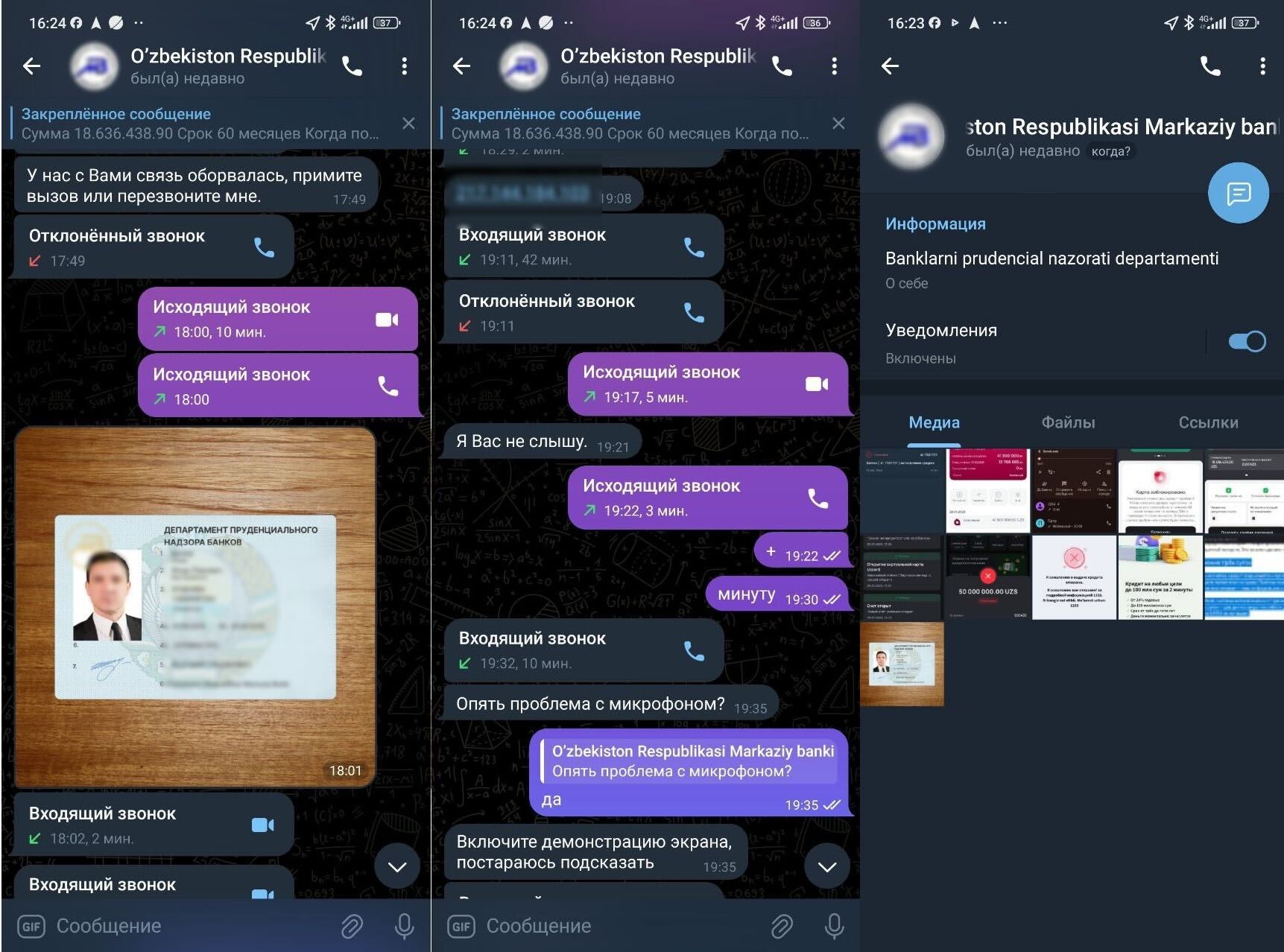

- More complicated fraud cases are carried out by the means of social engineering. These schemes involve impersonation of bank/financial-service/telecom employees or services. In 60% of complaints, fraudsters posing as employees of a payment service or the Central Bank of Uzbekistan (CBU) were implicated. Fraudsters call their victims and introduce themselves as an official employee of the bank or government with the claim that their bank account has been compromised and there has been an attempt from fraudsters to take a loan in their name. Fraudsters convince the victims in order to reject their credit applications they have to pass a verification process which is carried out through a special bot in Telegram. After getting personal information such as passport, and in some cases, FaceID details of the victim, fraudsters complete multiple credit loan applications prepared in advance. Money from credit loans are taken out from the victim’s account with the help of another online, yet vulnerable product – electronic wallets.

In some other cases, scammers in disguise of bank workers send phishing messages to victims via various social platforms like Telegram, Facebook, or Instagram with “better or lower percentage” credit loan offers. Upon accepting the offer victims are requested to complete “credit confirmation payment” or “credit insurance payment” by electronic payment services or money transfer to the card.

Social engineering: initial contact and trust establishment

A social engineering attack usually starts with the scammer initiating contact with the victim. This often happens through a phone call or sometimes a message. The scammer pretends to be a trusted representative, such as a bank employee or official. To gain the victim’s confidence, the scammer may even know and use the victim’s full name or other personal details. This technique exploits the victim’s trust in legitimate institutions.

During the conversation, the scammer warns the victim about some suspicious activity on their account. For example:

- An attempt to change the phone number linked to the bank card.

- Unusual transactions or loans being opened without the victim’s knowledge.

- That the client is currently being targeted by fraudsters.

All these messages are designed to scare the victim and push them into making quick, impulsive decisions. The scammer deliberately creates a sense of urgency, claiming that action must be taken immediately, otherwise it will be too late and the victim may lose a significant amount of money. This psychological pressure is a key part of their scheme. Scammers intentionally overwhelm the victim, giving them no time to compose themselves, calmly assess the situation, or verify the information they received. Under stress and panic, the victim becomes much more susceptible to influence and more likely to follow the scammer’s instructions, even if those instructions seem suspicious.

Figure 3. Example social engineering call where fraudsters, disguised as bank staff, warn a potential victim of suspicious account activity and the need to act fast.

Use of SMS stealers

Before 2025, with fewer anti-fraud defense mechanisms, one of the most common fraud schemes involved the use of malware. Once initial trust was established, scammers would instruct victims to download a ‘special banking app’ to supposedly resolve an issue. Links to these apps were often sent via messaging platforms like Telegram or WhatsApp. In reality, the app was a malicious program known as an SMS Stealer, which secretly forwarded all incoming text messages — including sensitive verification codes — to the attacker without the victim’s knowledge. With these verification codes, fraudsters could gain access to the victim’s accounts, allowing them to perform a range of financial transactions such as withdrawing funds; and with leaked personal information, even take out loans.

Banks fight back, but people are the weak link

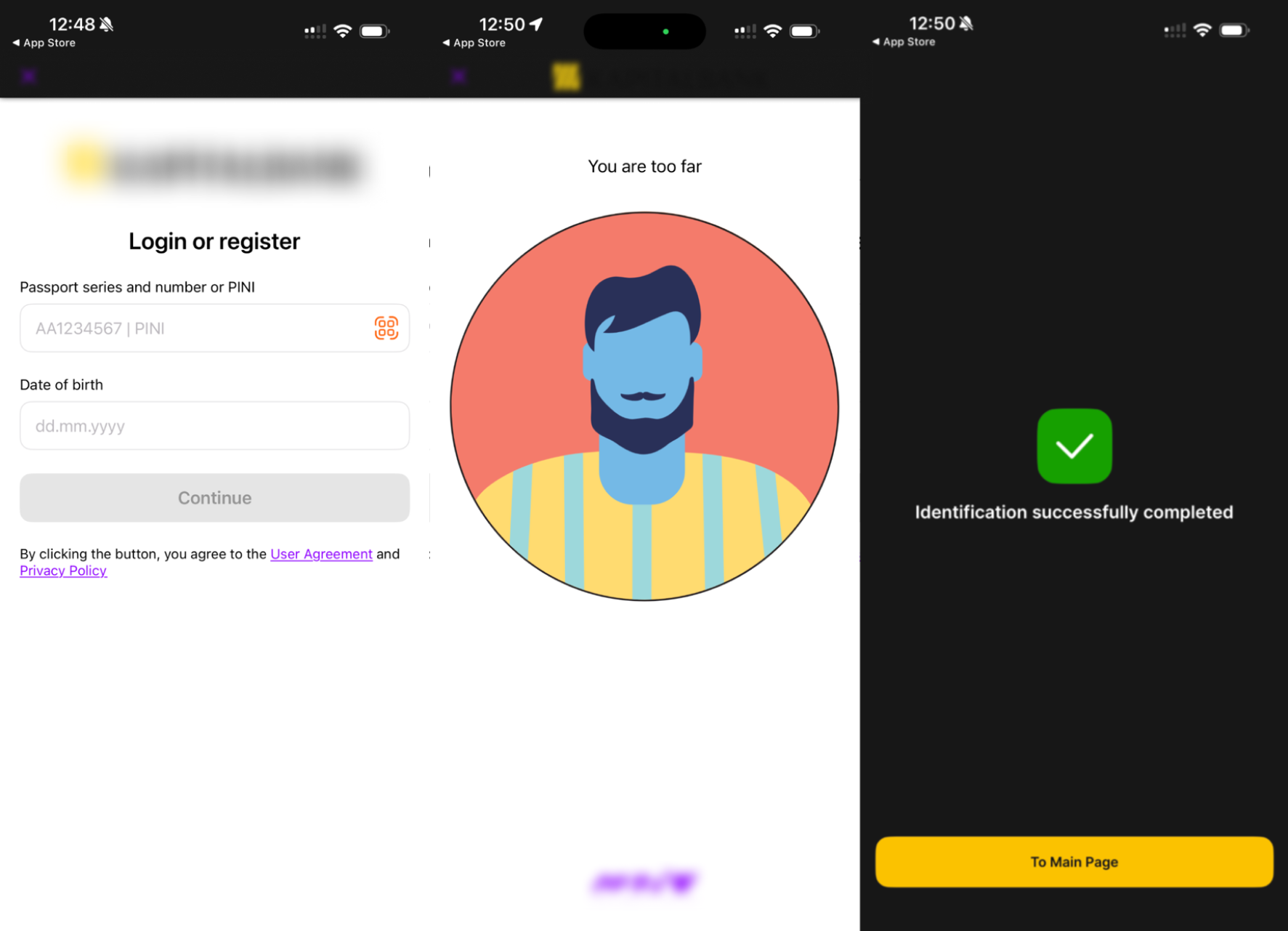

Starting in 2025, new rules from the CBU came into force to better protect people from credit fraud. Clients must now complete identity verification (for example, through MyID biometric facial recognition) both when logging into their banking account and when applying for a loan. The first check happens when the client submits the loan request, and the second check happens before the money is sent to the client. Because of these rules, loan scams and financial losses as a result of malicious apps have been reduced.

Figure 4. Example MyID biometric verification now required by banks.

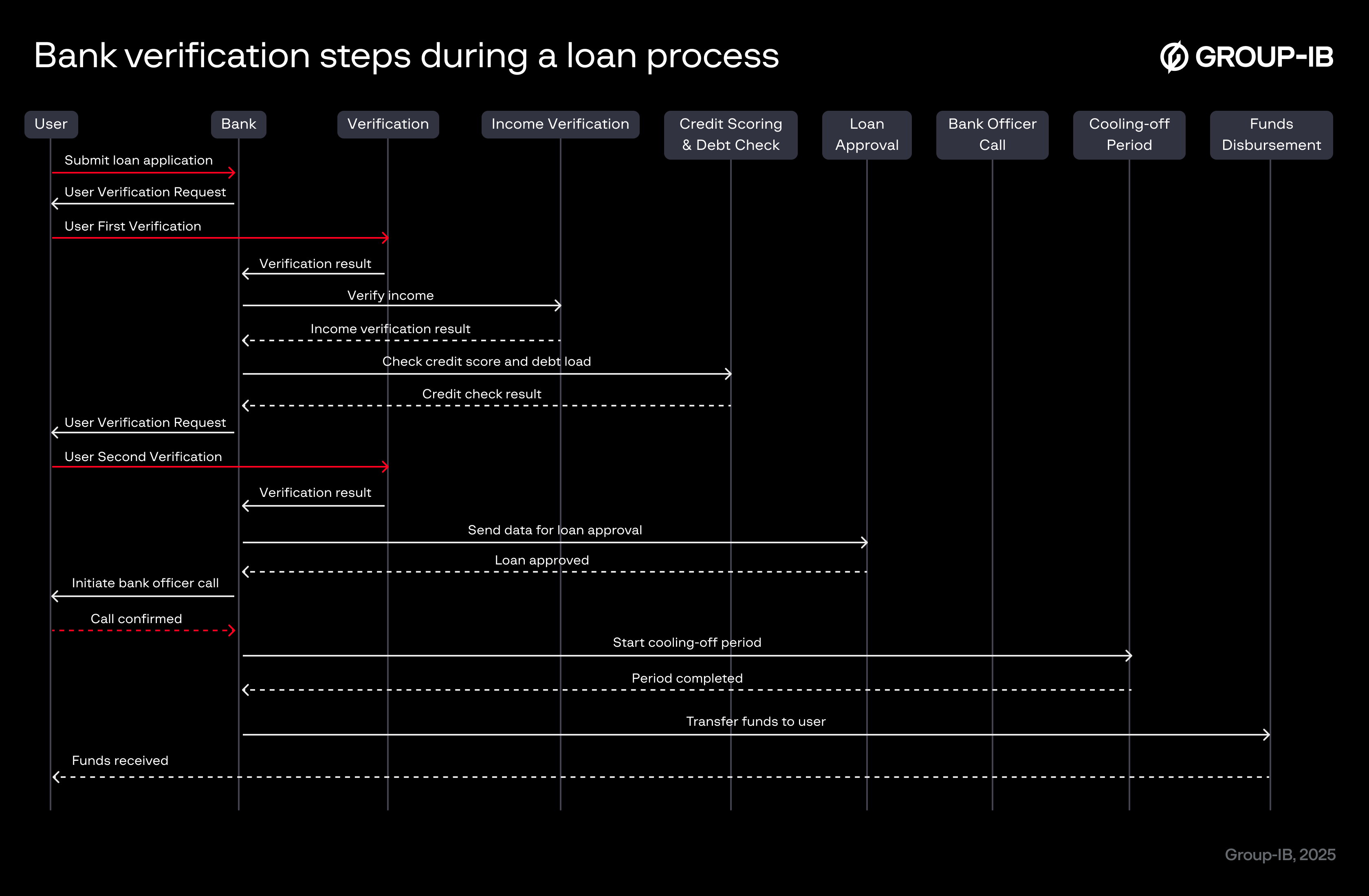

The next protection step is a confirmation call from the bank. This call is now a mandatory part of getting an online loan. Clients do not receive the money until a bank representative contacts them to make sure they know about the loan and really applied for it themselves.

After all checks and procedures are completed and the loan is officially approved, there is one last step — a freeze period. After approval, the money is not available immediately; it usually takes several days before it is disbursed. This delay is intended to give potential scam victims time to calm down, think clearly, and, if necessary, call or visit the bank to cancel the loan if it was taken under pressure, in a rush, or in an emotional state.

Additionally, every individual can set a voluntary credit ban, which prevents any loan from being issued in their name until they lift the ban themselves.

Figure 5. Bank verification steps during a loan process. Red arrows indicate points susceptible to social engineering.

However, even with all these protections, banks cannot fully prevent social engineering attacks. Victims often lack knowledge about fraud techniques and how the banking system works, making them susceptible to manipulation or intimidation. Scammers are very experienced in social engineering and can apply emotional pressure on the victim every step of the process, ensuring the completion of identity checks and loan confirmation during the real bank call. After the freeze period, when the victim receives the money, they may be convinced to transfer it to a ‘safe’ account, which is actually controlled by the criminals. Once the victim transfers the money, the scammers stop responding, and the funds are already moved to other fake accounts, making recovery almost impossible.

When victims finally realize they have been scammed, they’re often left with no money or large debts, shocked that they willingly handed it to the scammers themselves.

Understanding the vulnerabilities that enable credit fraud

What are the main causes of credit fraud incidents?

- Low consumer financial literacy & data awareness. Many citizens are unfamiliar with “personal data hygiene” and how the process of digital banking and online verification works. As a result, they fall prey because they don’t recognize the red flags, share personal data too easily, or assume that “if a bank asked, it must be real”. This was predominantly the case when the credit could be taken out on someone’s name without biometric verification and mere usage of passport and verification code sent to the phone number.

- Management failure and exploitation of authority by bank workers. 34% of credit fraud activities in Uzbekistan are associated with calls from a “bank worker” or “government official”. There were several incidents in which current or former employees of the banks have exploited their privileged access to customer data to apply for loans in clients’ names without their notice which suggests weak supervision, inadequate audit trails and lack of security compliance within the banking structure.

- Failure of bank’s internal verification, insufficient due diligence and lack of risk control – there were cases in which the applicant with only one bank who had never taken a loan before, somehow received loans from multiple banks prior to legislation on investigation of the client’s credit history in two stages. Cases like this illustrate the lack of systematic approach in checking the risk profile of the customers by heavy reliance on self-reported data from customers and issuing the loan on incomplete information.

Further measures taken by Uzbekistan authorities to prevent credit fraud

Until recently, some online loan apps and bank apps did not enforce strong biometric checks or identity proofing, making it easier to spoof identity. The CBU introduced a temporary procedure for online loan issuers requiring biometric identification and a two-stage credit-history check.

It also advised the use of a new free service introduced by CBU to block any loan applications called “Ban on signing a credit agreement” from MyGov application. This blocks any activity related to taking out a loan in the name of the person. Between June and July 2025, ~73,000 Uzbek citizens have already signed up for this service.

From November 2025, victims of online credit fraud schemes may now have their debt collection cancelled in circumstances where it is established that a loan was issued without their knowledge. If it is proven that an online credit was fraudulently taken out in a citizen’s name, banks may be required to suspend or void the claim for repayment. While this marks a significant shift in protecting individuals who had been a victim of digital credit fraud, it raises two new issues related to “true fraud” and “fake fraud” where borrowers may falsely claim to be victims in order to avoid repaying legitimately obtained loans.

Conclusion

The rise of credit fraud in Uzbekistan reveals how rapid digitalization of financial services has created both opportunities and vulnerabilities to customers. As banks are expanding their online lending services, fraudsters are exploiting gaps in verification systems, social engineering, and low financial awareness among citizens. The government of Uzbekistan has been making serious efforts to circumvent these threats by introducing new legislations, increasing customer awareness, and protecting consumer rights.

Recommendations

To protect against fraud, we recommend that end users and businesses follow these risk mitigation recommendations.

For Businesses:

- Implement a user session monitoring system, such as Fraud Protection, to detect infected devices, unusual account activity, and logins from suspicious devices.

- Conduct regular anti-fraud training for employees and public education campaigns for customers to improve digital hygiene and scam recognition.

- Share anonymized fraud intelligence and behavioral indicators to identify recurring fraud patterns and cross-institutional schemes.

- Before issuing a loan, conduct a full analysis of user activity for social engineering or atypical behavior.

- Notify users with push notifications about attempts and instances of loans taken out in their name in the mobile app.

For End-users:

- Be cautious when receiving unexpected calls, especially if the caller requests your personal or financial information. If someone introduces themselves as a bank or government employee, hang up and call the official number from the organization’s website. Fraudsters often use disposable or spoofed numbers.

- Never share your personal information over the phone or via other messaging services with individuals claiming to be bank or government employees. Do not share personal information such as card details, passwords, or passport information via social media messaging services, as these are not official means of communication.

- Check your credit reports or online banking apps for unfamiliar loans or accounts. Early detection can prevent serious consequences.

- If you have been a victim of credit fraud, it is recommended that you immediately contact your bank and report the incident.

- Enabling self-exclusion for the most socially vulnerable individuals. Even if all data is provided, it will be impossible to take out a loan.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is credit fraud and how does it affect victims?

Credit fraud occurs when a loan or credit is issued using someone else’s identity without their consent. Victims in Uzbekistan often only discover the fraud when their application is rejected or debt collectors contact them.

Why is credit fraud increasing?

Online lending is rapidly growing, making loan approvals faster and more convenient. This shift has also opened opportunities for fraudsters to exploit verification gaps and social engineering. In 2024, reported cases increased by 42% compared to 2023.

What are the techniques that scammers use?

Some of the most common methods used by scammers in credit fraud include:

- Impersonating bank or government officials

- Obtaining victims’ passport details, FaceID, and OTP verification codes

- Using phishing links or malicious apps (SMS stealers)

- Exploiting internal bank employee access

- About 34% of incidents involve fraudsters posing as authority figures.

How do social engineering scams work?

Scammers create panic by claiming that someone is trying to take a loan in the victim’s name, then guide them to “verify” identity via Telegram bots or fake apps — ultimately gaining full access to personal information and accounts.

How do cybercriminals launder stolen funds?

They often use electronic wallets or mule accounts to quickly disperse loan funds into untraceable channels.

Fraud Matrix

| Tactic | ID | Technique | Procedure |

| Reconnaissance | T2105.001 | Account Stuffing | Fraudsters use lists of username-password pairs obtained from previous data breaches to gain unauthorized access to user accounts. Account stuffing attacks are typically automated, using scripts or tools that rapidly input username-password combinations. |

| Reconnaissance | T2105.003 | Buying Compromised Accounts | Fraudsters obtain compromised accounts through illicit channels such as dark web marketplaces, hacking forums, automated tools, and Telegram black-markets. Compromised accounts can result from various methods including phishing attacks, data breaches, weak passwords, or malware infections. |

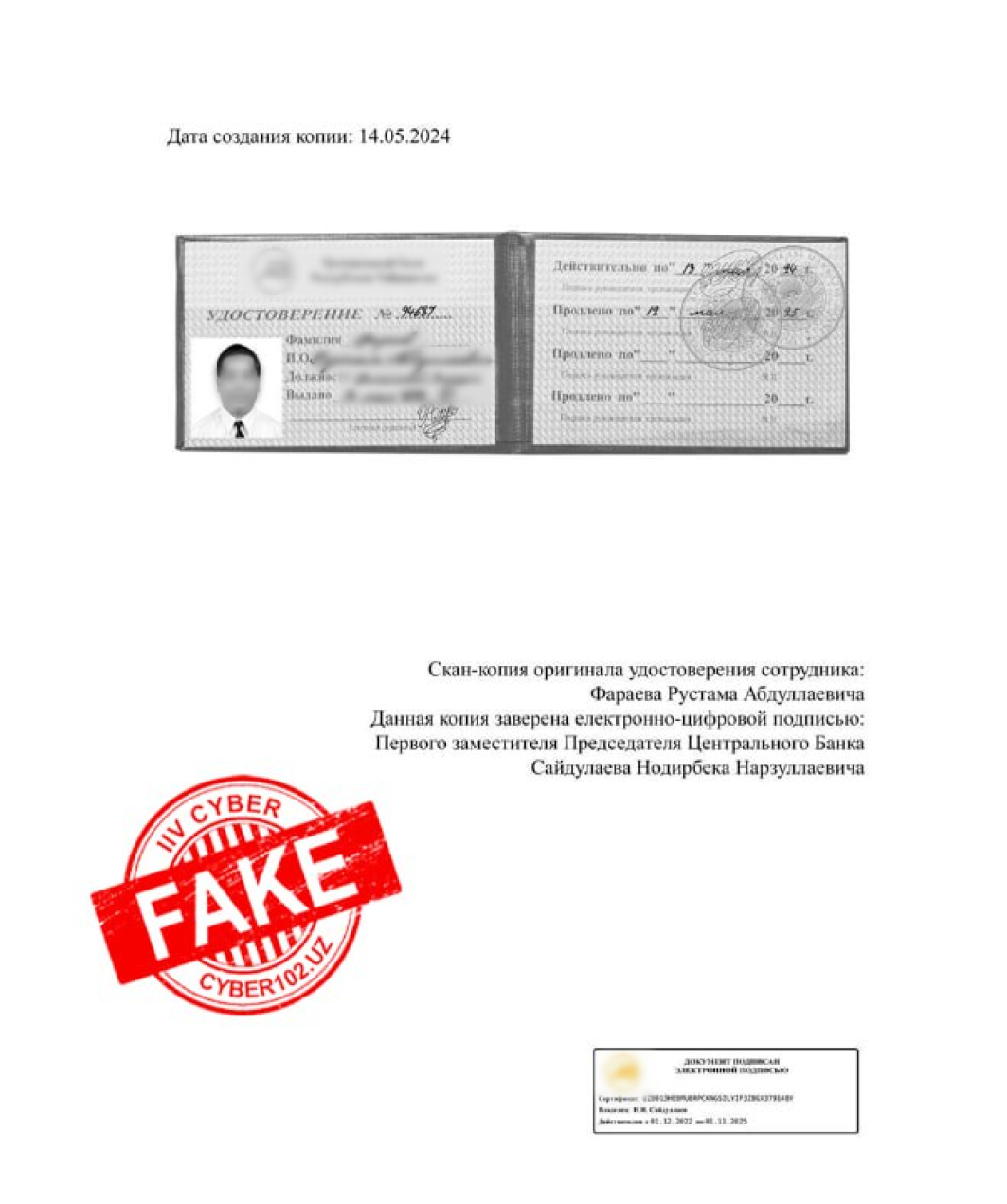

| Resource development | T2139 | Creating Fake Documents | By forging documents such as identification cards or passports of government officials or Central Bank workers, they falsify identities, deceive authorities, or fabricate evidence to facilitate credit fraud. |

| Resource development | T2165 | Phishing Resource | Fraudsters leverage phishing resources as a critical tool to support their illicit activities, targeting individuals and organizations through deceptive messages or websites. These resources are designed to mimic legitimate entities, such as banks, government agencies, or trusted companies, with the aim of tricking recipients into disclosing sensitive information, such as login credentials, financial details, or personal data. |

| Trust abuse | T2004 | Pushing to Loan | Fraudsters initiate contact through various channels, including phone calls or messages, posing as representatives from reputable financial institutions. They may charge upfront fees or processing fees for the loan application, steal sensitive personal or financial information for identity theft, or deploy other scams disguised as loan-related services. |

| Trust abuse | T2077.009 | Fake Fraud Warning | Fraudsters contact the victim via phone calls, emails, or text messages, claiming to represent a reputable organization and alerting them to suspected fraudulent activity on their accounts. They use this technique to manipulate victims into providing details such as account numbers, passwords, security codes, or even personal identification information, falsely claiming that the information is necessary to confirm the authenticity of the warning or secure the victim’s accounts. |

| Trust abuse | T2077.006 | Fake Loan Request | Fraudsters pose as loan brokers and portray themselves as knowledgeable professionals in the lending industry. They promise attractive loan terms, quick approval processes, or guaranteed funding to entice victims into sharing confidential details such as income verification, banking information, or personal identification number. |

| Trust abuse | T2104 | Bank Employee Impersonation | Fraudsters pose as customer service representatives or security personnel, leveraging the authority and credibility associated with bank employees. They claim to require account verification, offer assistance with fraudulent activity detection, or request sensitive information for security purposes, deceiving victims into providing details such as account numbers, passwords, or verification codes. |

| End-user interaction | T2177 | Pushing to Install Malware | Fraudsters convince victims to download and install malicious apps on their devices, the malware gains unauthorized access and control over the device’s functionalities. This enables fraudsters to steal sensitive personal information, to intercept communication data, and to deploy additional malware to exploit the compromised device further. |

| Credential access | T2180 | Credentials Capture | Credentials Capture involves the surreptitious acquisition of sensitive login credentials, including usernames, passwords, and security questions, often through deceptive means such as phishing attacks, keylogging malware, or fake login pages. Fraudsters trick victims into unwittingly disclosing their credentials. Once obtained, these credentials are used by fraudsters to gain unauthorized access to victims’ accounts, allowing them to perpetrate identity theft and financial fraud. |

| Credential access | T2124 | Phone Number Capture | Fraudsters trick individuals into providing their phone numbers through deceptive means such as fake websites. Once fraudsters obtain these phone numbers, they use them as part of multi-factor authentication processes or to impersonate the victims during account recovery procedures. |

| Credential access | T2001.002 | Push Interception | Fraudsters infect devices with malware capable of intercepting push notifications This malware collects data without the victim’s knowledge, allowing fraudsters to bypass authentication measures and gain unauthorized access to the victim’s accounts. |

| Credential access | T2001.001 | SMS Interception | Fraudsters infect devices with malware capable of intercepting SMS, a technique used to capture authentication codes or sensitive information sent to the victim’s mobile device. |

| Account access | T2069 | Access from Fraudster Device | Fraudsters gain unauthorized access to victim accounts and carry out credit fraud related activities from their own devices. |

| Perform fraud | T2138 | Loan | Fraudsters deceive financial institutions or lenders into providing loans using fabricated or stolen identities. Once the loan is approved and the funds are disbursed, the fraudsters abscond with the money from the loan without any intention of repaying it, essentially stealing the borrowed funds. |

| Laundering | T2020 | Mule accounts | Fraudsters exploit mule accounts by recruiting individuals, often unknowingly, to receive and transfer illicit funds. These individuals, referred to as “mules,” are persuaded through fake job offers or other deceptive means. Once funds are deposited into these accounts, the mules are instructed to transfer the money to other accounts or withdraw it as cash, effectively laundering the funds and concealing their illicit origins. |