Background

Between 2013 and 2015, cybercrime was gaining momentum worldwide, posing significant threats to financial institutions and their customers. Cybercriminals increasingly targeted mobile platforms, especially Android, which presented new vulnerabilities and fewer security controls than traditional desktop environments. In Russia and other CIS countries, financial institutions and individual users faced an unprecedented wave of banking malware attacks. Organized cybercriminal groups like Cron and TipTop were refining their techniques, using malware that could intercept banking credentials, manipulate SMS codes, and conduct unauthorized transfers.

Against this backdrop, Group-IB identified Reich 5, a cybercriminal network in Russia and Ukraine that epitomized the evolution of cybercrime tactics during this period. Known for using the Svpeng banking Trojan, Reich 5 infected over 340,000 Android devices to steal money from people’s bank accounts. Their operation involved the use of Nazi symbols in the control panel. The group spread malware through SMS messages in which the download link was made to look like an Adobe Flash Player update, intercepting users’ banking SMS notifications and authorizing fraudulent transactions without their knowledge.

Group-IB leveraged its proprietary Threat Intelligence technology and worked closely with the affected bank and Russian law enforcement to address the threat.

Behind the scenes

The story began when several individuals approached Group-IB after experiencing unauthorized withdrawals from their bank accounts. Group-IB examined their smartphones and found that a malicious mobile application had replaced the Google Pay interface on the device screen with an identical fake. When the device owner entered their bank card details (card number, cardholder information, expiration date, and CVV code) into this interface, the data was sent directly to the attackers’ server.

Group-IB’s analysis revealed that the malicious apps shared a similar functionality and coding style, leading the Investigation Team to a hacker group known as “Reich 5.”

Impact

The group’s malware campaign had led to the theft of more than 50 million rubles ($930,000) from over 30,000 bank clients and was a grave concern for Russian banks. The collaboration between Group-IB, major Russian banks, and law enforcement helped to dismantle Reich 5 and prevented further financial losses. By March 2015, Group-IB had identified the Reich 5 group’s key members, which enabled the police to conduct targeted raids and arrest the suspects.

Storyline

The first reports of this malicious program appeared in July 2013. It was immediately clear that the Trojan was designed for bank account theft. Over time the Trojan evolved, adding new features that made thefts even more efficient.

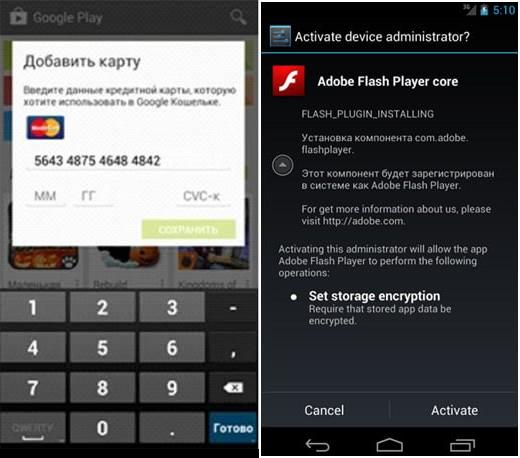

The malicious program was spread through SMS campaigns containing a link to download the malware, made to look like an Adobe Flash Player update. This free software is widely used, especially for video playback. During installation, the program requested administrator privileges. Once installed on the mobile device, the Trojan would find or request information about the balance of the linked bank cards and hide incoming bank SMS notifications.

By manipulating SMS messages, attackers could transfer money to their own accounts without the need for further authentication. Online transfers could be confirmed by sending an SMS to the bank’s dedicated number, accompanied by a code the bank — also sent via SMS. The malware showed no signs of its presence on the tablets or smartphones. The devices appeared to function normally, but unseen processes were running in the background.

Later, the group began collecting credit card data using phishing websites. Once the malicious program infected a mobile device, it checked if the Google Play app was running. If the user opened Google Play, the Trojan overlaid its own window on top, prompting the user to enter their bank card details. Once entered, the details were instantly sent to the attackers’ server, where malicious scripts verified the card details. If valid data was detected, the attackers received a real-time notification via the Jabber protocol.

Figures 1-2. Fake windows displayed by the Trojan

Next, the hackers created phishing pages targeting specific Russian and Ukrainian banks. This time, instead of card details, the attackers sought to intercept login credentials for online banking accounts. When a user opened their banking app, the Trojan replaced the genuine window with a phishing overlay in which users unknowingly entered their login information. Their credentials were immediately transmitted to the attackers’ server. Armed with the login, password, and access to SMS messages (including those containing bank confirmation codes), the attackers could perform bank transfers without anyone noticing.

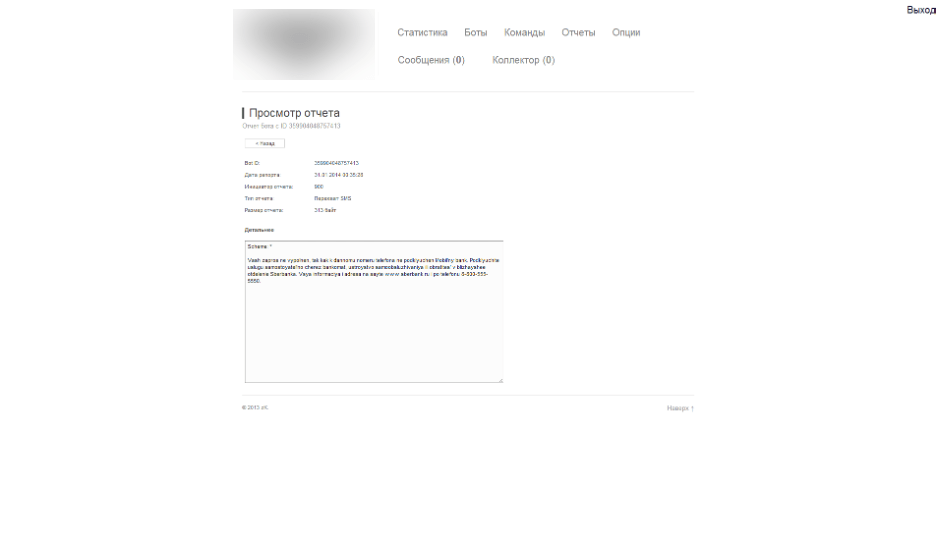

Figure 3. A Nazi-themed malware control panel of the Reich 5 gang. Report on an intercepted SMS message from the infected device

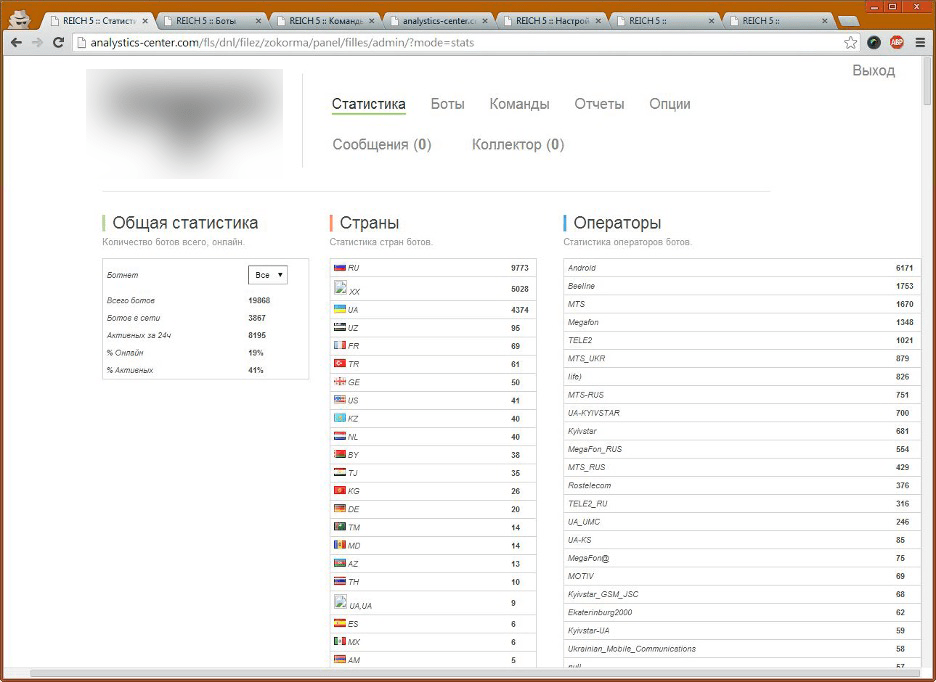

Figure 4. Statistics for infections in devices, countries and cell operators in the control panel

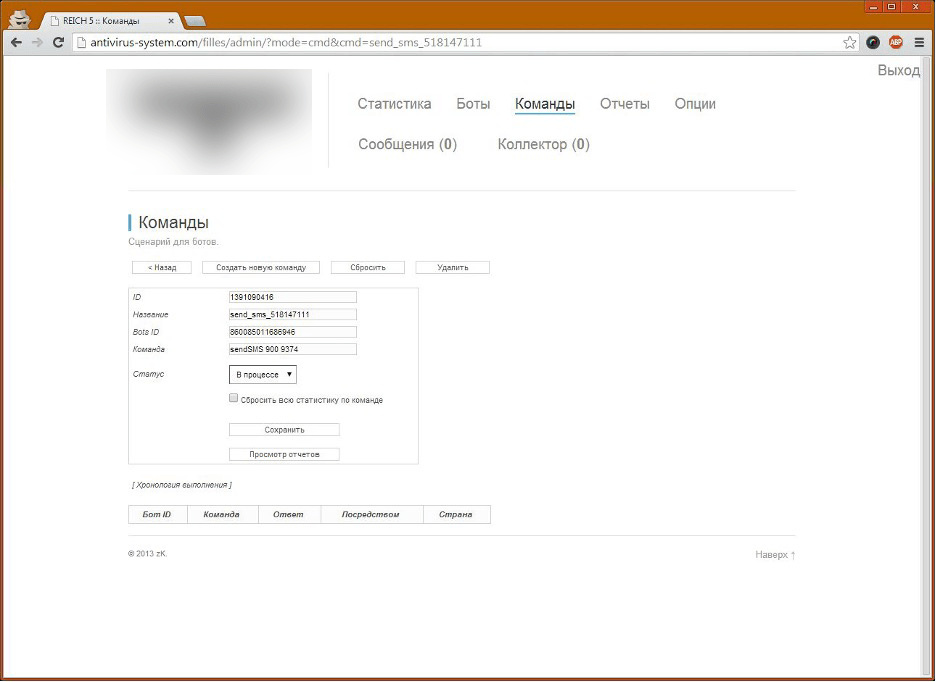

Figure 5. Sending messages

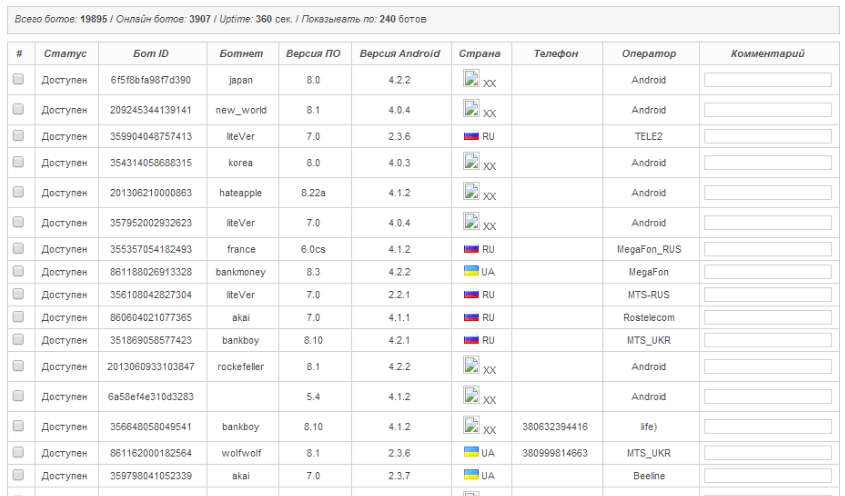

Figure 6. Svpeng control panel: Status, Bot ID, Botnet, OS version, Android version, Country, Phone number, Telecoms operator, Comments

Most banks had a daily limit of $500 to $600 for such transactions via SMS banking. However, this amount was perfectly sufficient for the developers of “Reich 5”. The fraudsters were able to steal such sums from the same person’s card every day without their knowledge. Victims would only discover the theft when, for example, they were informed that they did not have enough funds to complete a purchase in a store or online.

To launder the stolen money, the criminals used a common scheme. Across various cities, they enlisted so-called “money mules” — individuals who opened bank accounts and registered cards in their own names. The fraudsters transferred the funds from the stolen cards to these accounts, after which the money mules quickly withdrew the cash. The entire process took mere minutes, which made it exceedingly difficult to trace and intercept such operations.

And justice for all….

In April 2015, Russian law enforcement detained four members of Reich 5, including the lead developer of the Svpeng Trojan, a 25-year-old individual from the Chelyabinsk region. During the police raids, officers seized laptops, SIM cards, and mobile devices linked to the malware. Thanks to Group-IB’s support, Russian authorities were able to identify and prosecute these individuals, who were charged under Russian law for theft and for the creation and distribution of malware.

Conclusion

The operation highlighted both the expanding role of cybercriminal groups in mobile banking fraud and the critical need for public-private partnerships between cybersecurity firms like Group-IB and law enforcement agencies. By sharing threat intelligence and forensic insights, Group-IB provided Russian authorities with the tools needed to uncover Reich 5’s infrastructure and members, trace its operations, and bring its members to justice.

This operation was one of the first cases in Russia when cybercriminals and malware developers were arrested for thefts from bank accounts using Android Trojans. The malware may not have just been used to target banking customers in Ukraine and Russia, but also to scan for Western banking apps, which means that the arrest prevented the campaign from escalating further worldwide and protected thousands of potential victims. This case also showed the critical importance of public awareness in cybersecurity — simple acts like avoiding downloads from unverified sources and heeding device warnings could prevent such attacks.