When we talk about responding to incidents that don’t involve malware, insider threat is usually one of the first things to come up. The picture that comes to mind is a specialist who was unjustly fired and wipes crucial data in revenge, or a shareholder dispute that leads to correspondence being exfiltrated…. or even an employee who decides to sell their corporate VPN access.

Investigating such incidents often results in a clash of biases. Two perspectives will likely emerge in a single war room briefing. On one side, there’s the incident responder who would lean toward blaming external hackers, as such threats dominate in their experience with cyber security. They think in terms of hacker groups, phishing kits, and the cyber threat landscape. On the other side, there’s the business owner who tends to suspect threats from the inside, competitors or a rogue employee. They are likely to have more insight into detecting corruption or corporate conspiracies than a cybersecurity expert would. In this edition of the Untold Story of Incident Response, Group-IB’s new series detailing some of the most notable cases faced by Group-IB’s Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) team during their more than 70,000 hours of diligent work helping organizations respond to cyber attacks, we’ll investigate which of them is right…

How it all started

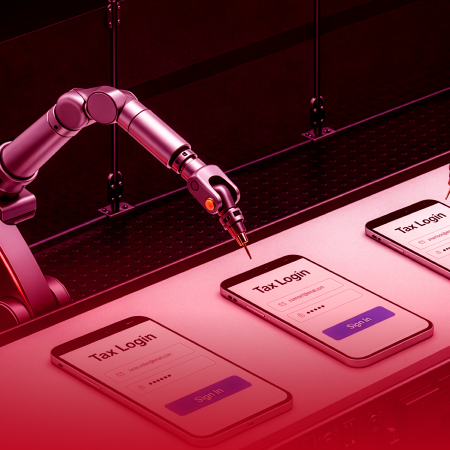

We first became involved in an incident for a small local payment system following a conversation similar to the difference of opinion described above. A hacker had found a way to send specific requests to an open payment gateway. Within 30 minutes, numerous requests for transferring small amounts of money were dispatched from various IP addresses within the TOR network. As a result, the company lost a great deal of money.

The company’s co-owners believed that only a programmer who built the payment system could have sent such requests to a payment gateway. So the very first idea was therefore to examine the employee’s mobile devices and analyze the employee’s emails from the past few years using e-Discovery and other information-gathering methods.

Before attempting to prove the hypothesis, our incident response team decided to look more closely at the pattern of the payment requests. The team discovered that the perpetrator had used TOR addresses, that the attack was clearly premeditated, and that money mules were involved. Which of the following is a potential insider threat indicator? Why not first check for an internal network breach? Looks like potential insider threat would have to wait for some time.

Our incident response engagement started with analyzing network logs and VPN connections and looking for associations with TOR addresses. The Group-IB DFIR team performed basic checks for implants within the corporate network, with a view to identifying signs of a few hacker groups that were attributed preliminarily based on their country of operation and on which payment system they chose to target. Meanwhile, we instructed one of the co-owners — the lead developer and the only programmer who was excluded from the suspects to create a list of servers or endpoints containing the documents that someone on the outside would need to study in order to send malicious requests to the payment gateway.

The moment we had some doubts

The corporate network was surprisingly small and unusually clean. It seemed to have slipped under the radar of regular phishers, malicious emails, internet scanners, and the usual plethora of online threats. Given that we made no significant findings during the basic search, we decided to focus on critical information.

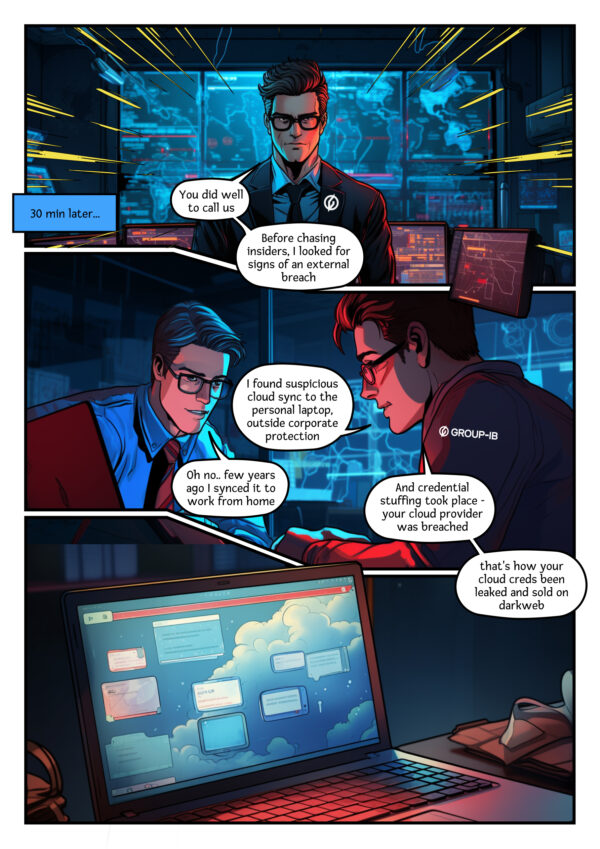

The lead developer informed us that all the essential information was in his head (unfortunately, that had not been logged) and on his workstation. Going on our intuition and years of experience, we asked him to bring in his personal laptop for forensic examination.

How do we investigate without a single lead?

When the response team’s hypotheses have predictive power, it leads to one of the most satisfying feelings you can have during an investigation. We never look through logs aimlessly, searching for illegitimate actions. Instead, we dig deep and examine specific hypotheses, already anticipating what we might find.

And we found plenty! The lead developer had set up for his documents to synchronize to a cloud storage system on his personal laptop years ago, and then forgot about it. This means that, for years, a fully up-to-date set of documentation about the payment system (including internal system structure, logins, and passwords) had been stored on the lead developer’s personal laptop, outside the corporate security perimeter. So when the famous cloud storage was breached, the passwords were leaked and sold on the dark web.

When the attacker purchased access to the programmer’s personal cloud account on a dedicated leak site (DLS), he hit the jackpot. Further investigation revealed that the criminal had studied documentation relating to the payment system for months and trained himself so well that he was able to create similar requests to the payment system from the outside. In one day, he stole more than half a million dollars. The attacker got unlucky only once, though — when the Group-IB DFIR team found him. The mystery was solved and the ‘culprit’ was found to be a cybersecurity flaw, without ever having to investigate even a single insider suspect.

Recommendations

- The Group-IB DFIR team recommends conducting a Compromise Assessment every few years as part of a regular check so as to be aware of potential compromise

- Do not underestimate two-factor authentication (2FA) as a basic security measure to be used on every employee’s account

- Regular digital hygiene training can never hurt, and not just for new team members

- Apply secure code practices in your development and regularly conduct penetration testing and security audits on your assets