Introduction

Fraudsters have devised a sophisticated social engineering scheme that has proven its effectiveness in deceiving customers in the Middle East into disclosing their credit card credentials. This scheme involves impersonating government officials to gain the trust of its victims and utilizing Remote Access Software to steal user’s sensitive data. The scam specifically targets individuals who have previously submitted commercial complaints to the government services portal, either through its website or mobile app, regarding products or services purchased from online merchants. The fraudsters exploit the victims’ willingness to cooperate and obey their instructions, hoping to receive refunds for their unsatisfactory purchases. The financial impact of this scheme is significant due to its ease of execution and the fraudsters’ ability to make several fraudulent transactions from carefully selected merchants during a single fake support session.

The Evolution of Fraud Schemes: Impersonation and Remote Access

Over the past decade, governments and their financial institutions in the Middle East have launched several fraud awareness campaigns to educate their users and citizens not to share their sensitive data or One-Time Passwords (OTPs). The campaigns made it increasingly difficult for the fraudsters to succeed using conventional social engineering tactics, which relied on the victims disclosing the OTPs their financial institutions sent to their devices. As a result, criminals have adapted by developing more sophisticated schemes designed to deceive even the most vigilant individuals.

Based on the findings of Group-IB’s Cyber Fraud Analysis in the Middle East, it has been discovered that a key feature of this scheme is to gain the victim’s trust by impersonating government officials while peeking into their sensitive data through Remote Access Software. It leverages a vulnerability in the local e-commerce system, where dissatisfied consumers can submit commercial complaints through the government services portal, in the hopes of receiving a refund for their purchases. Fraudsters posing as government representatives contact these consumers under the guise of assisting with their complaints. During this process, consumers unknowingly cooperate with the fraudsters, often following their instructions to install remote access software, which enables further exploitation.

Customer Complaints

Below are the genuine customer complaints gathered by the customer support service concerning fraud incidents:

Example 1

The partner reported that she was defrauded through a phone call from the number *******. During the call, she was instructed to download an official government application and AnyDesk. She then provided the number displayed in these applications. Subsequently, an amount of ***** was withdrawn from her credit card and ******* from her current account.

Example 2

The client reported receiving a call from an individual claiming to represent the government organization, offering to assist with an existing complaint in the system. The caller instructed her to download the legitimate government application and AnyDesk to proceed with the complaint resolution. Subsequently, unauthorized deductions were made without the client’s knowledge or consent.

Example 3

A call was received from someone claiming to be a government employee responding to a previous complaint. Subsequently, the following actions were taken, including the download of the AnyDesk program.

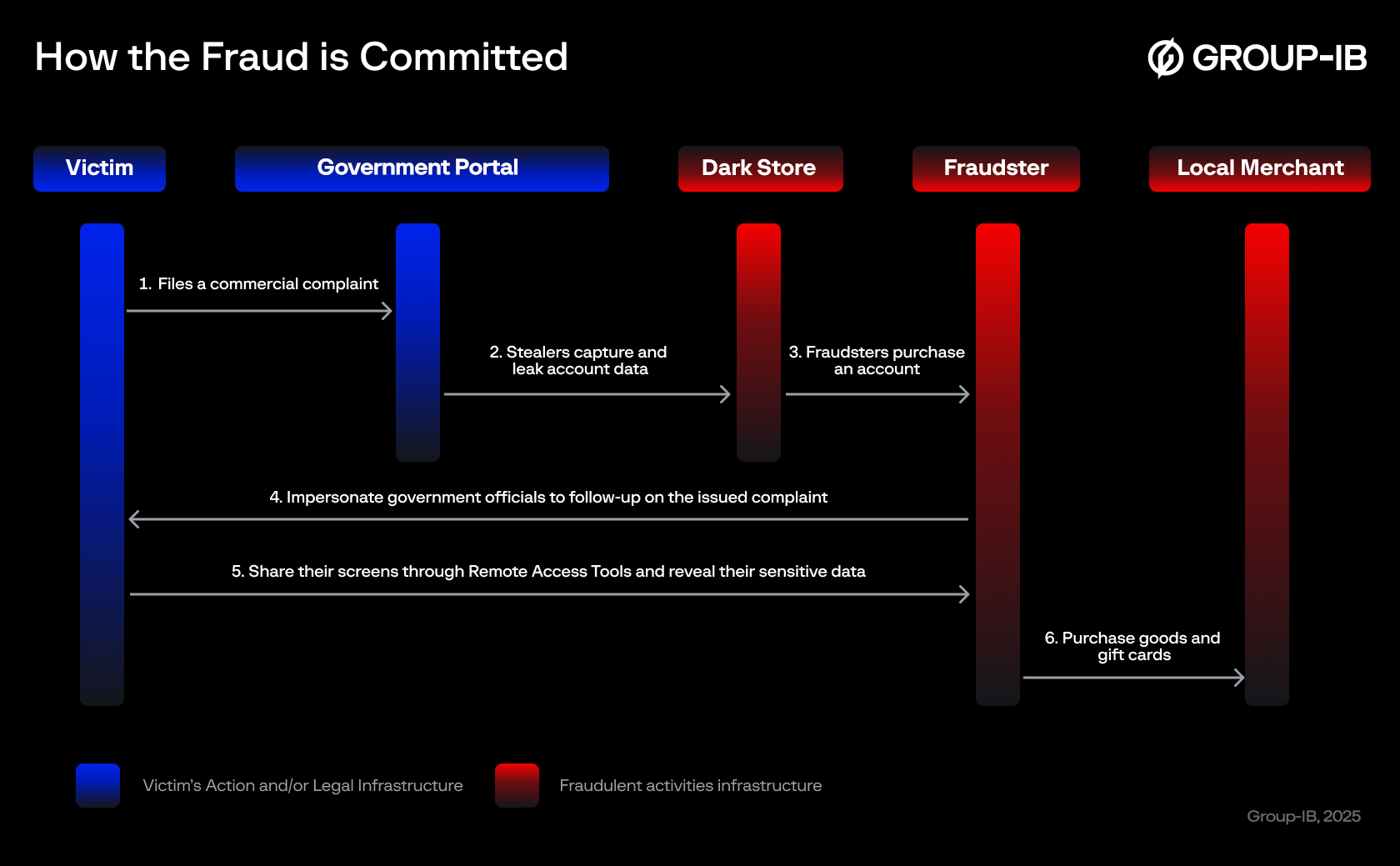

How the Fraud is Committed

Figure 1. A diagram of how an impersonation and remote access scam is carried out.

In a scenario illustrated in the diagram above (Figure 1), a consumer purchases a product or service from an online or physical store. If they are dissatisfied with the goods they purchased or services provided, they can submit a commercial complaint to an official government portal through its website or mobile app.

During the process of submitting a commercial complaint, the consumer has to provide their personal and contact information. Since the personal computer was previously infected with a special stealer program, the account details become available on the dark web. Fraudsters acquire this data as a part of their reconnaissance efforts. Once in possession of the information, they proceed to contact the victims, posing as government officials, claiming to assist in processing a refund for the complaint.

After gaining the victim’s trust, the fraudsters then instruct them to download an official application and a remote access app under the guise of registering the complaint. Once both applications are installed on the mobile device, the victim is asked to share their remote access code to enable the scammers to “provide support”. Once screen sharing is established, the scammers request that the victim upload a photo of their credit card to the complaints app. While the victim does so, the scammers steal the credit card details, preparing to make fraudulent online transactions. During this process, text notifications containing One-Time Passwords (OTPs) appear on the shared screen. The scammer then intercepts these OTPs and uses them to complete the fraudulent purchases.

One of the key elements in describing a scheme is the use of real customer information to gain the customer’s trust and ensure success in social engineering interactions. This situation becomes possible due to the widespread distribution of stealers.

How do stealers work?

A stealer is a type of malicious software (malware) specifically designed to extract sensitive information from a victim’s computer or device. The stolen data is typically sent to a command-and-control (C&C) server controlled by the attacker and can subsequently be sold on dark web marketplaces (Step 2 in Figure 1).

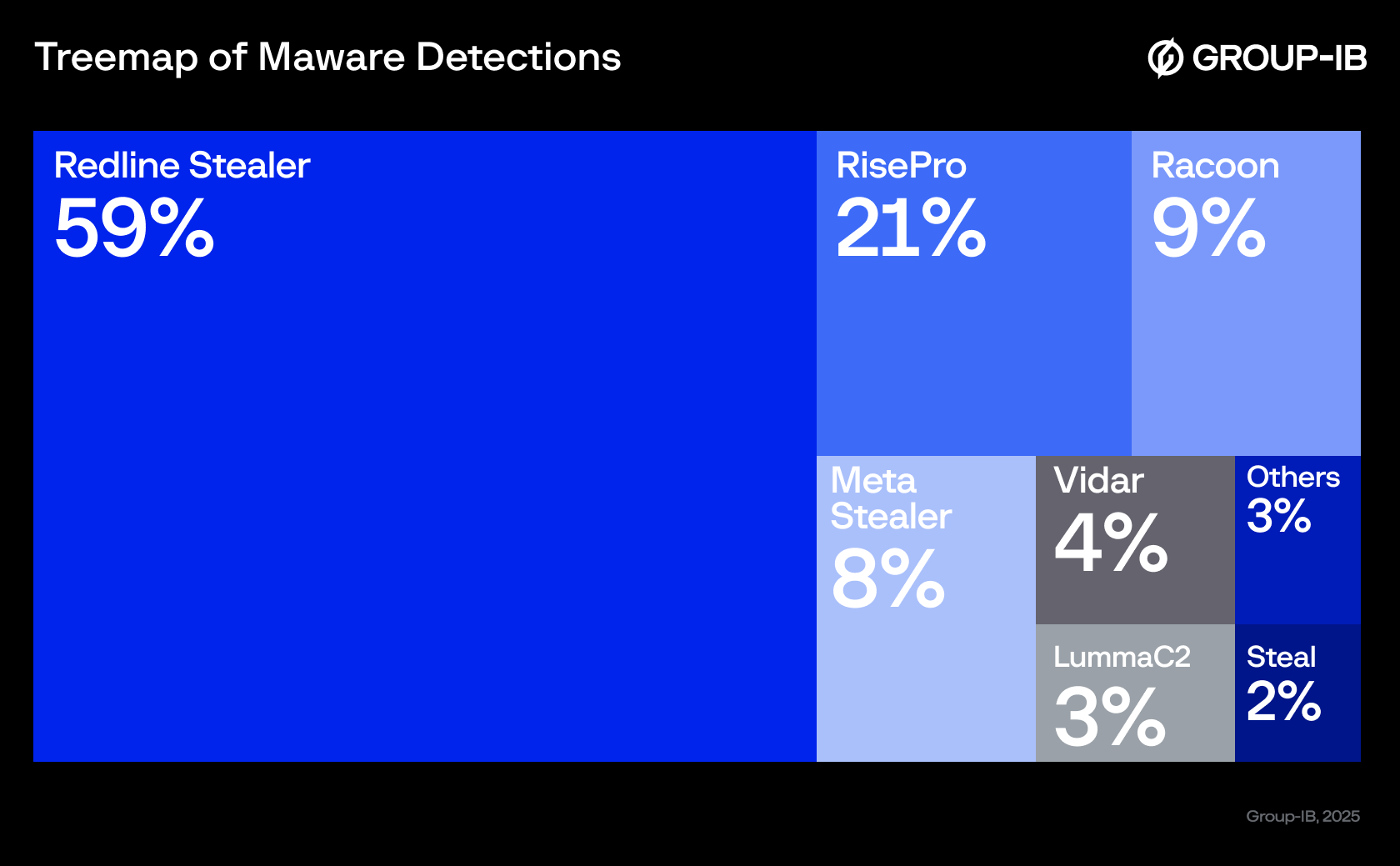

According to Group-IB Threat Intelligence data, breaches of government websites in the META region in almost 60% of cases are associated with the use of RedLine Stealer (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The treemap illustrates the percentage distribution of various malware programs used to steal accounts from official government platforms.

RedLine Stealer first emerged in 2020 and quickly gained popularity due to its affordability and ease of use, making it a go-to tool for cybercriminals. Malware specializes in stealing passwords, cookies, autofill data, cryptocurrency wallets, and other sensitive information from browsers and applications. It is commonly distributed via phishing emails, pirated software, and malicious websites, allowing attackers to conduct large-scale credential theft. RedLine’s user-friendly interface and accessibility on underground forums make it a significant threat in the hands of both novice and experienced attackers. Group IB Threat Intelligence customers can find more information about stealers and other malicious programs on the portal.

Victimology

In most cases, impersonation and remote access fraud target female consumers. Overall, the victims often have limited experience or expertise with technology and digital services. The victims are also motivated by the desire to receive a refund for the unsatisfactory goods and services they have purchased, which compels them to unwittingly cooperate with the fraudsters.

Figure 3. A screenshot of the Group-IB Threat Intelligence platform illustrating a large number of detected compromises from a government portal.

The Perpetrators

The fraudsters behind this scheme are likely native Arabic speakers proficient in the local accent, as the tactic involves them calling victims and pretending to be government officials.

The scheme is well-structured and complex, requiring a mature level of operations, organized infrastructure, and various specialized roles. It involves multiple stages, starting with data collection, preparing scripts for dialogues, proceeding to the implementation phase, which includes the use of RAT tools and performing transactions, and ending with the cashing-out and money laundering stages, which require extensive coordination, such as the creation and maintenance (farming) of mule and drop accounts, organization of reselling operations, and employing anonymization tools. As a result, such schemes on a wide scale can only be carried out by organized criminal groups.

Based on the findings of Group-IB’s Cyber Fraud Analysis, the geographical distribution based on IP address information linked to the opening of 3DS pages on fraudulent devices shows a pattern of IP usage originating from the Middle East region. Additionally, anonymization tools such as VPN, virtual machines, and dedicated IP ranges belonging to hosting providers have been observed in these fraudulent activities.

For Group-IB Fraud Protection customers: Please access our FP Intelligence portal for a more detailed report and tailored recommendations.

Cashing Out & Financial Impact

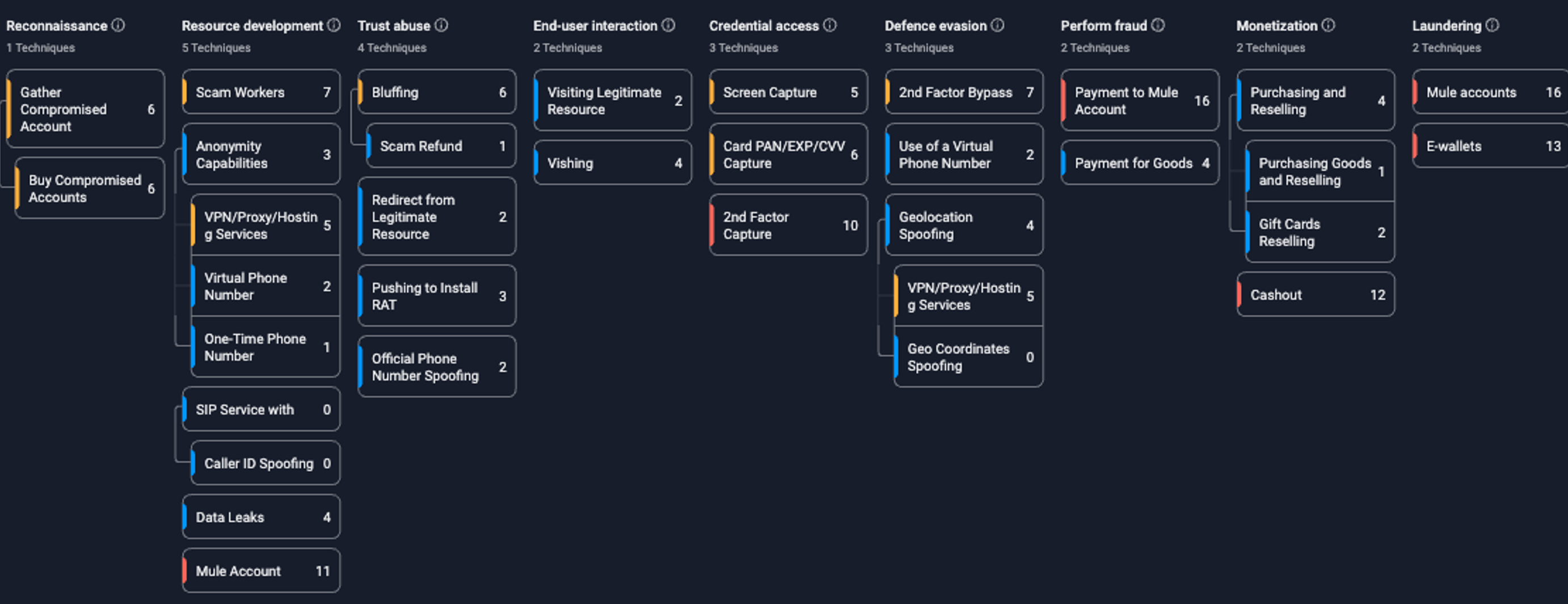

Figure 4. Group-IB’s Fraud Matrix, mapping the entire process of the scam.

As outlined in the Fraud Matrix for this scheme, fraudsters typically cash out the money scammed from their victims by making 3D-secured purchases of products or gift vouchers from local e-commerce retailers, as well as recharging local e-wallets (payment to mule accounts).

Payment for goods is considered to be one of the simplest and the most direct fraudulent methods performed, as it does not require the use of mule accounts or a series of transactions to hide the source of the funds.

Recharging e-wallets is also an effective method of stealing funds. Unlike the purchase and resale of goods, it requires additional preparation, such as the opening of mule accounts, and poses higher risks for fraudsters since the transaction can be blocked by the bank. However, it involves even greater financial losses for victims and offers a faster method of cashing out and withdrawing funds.

What makes this scheme more dangerous than others is the scammer’s ability to carry out multiple fraudulent transactions by intercepting OTPs from text notifications displayed on the shared screen via remote access software. Since these transactions are 3D-secured and the victims actively cooperate with the fraudsters, the resulting huge losses can not be recovered.

According to Group-IB’s Cyber Fraud Analysis, the average loss per transaction is approximately US$1,300 for incidents where transactions were performed through online stores. In general, such transactions are related to purchases of expensive electronic devices, the most convenient to resell.

In case of e-wallets usage and utilization of mules accounts, the average loss per such operations frequently reaches US$5,000, and the upper threshold depends on the customer limits. The total damage from an incident depends on the victim’s available balance and can amount to tens of thousands of dollars per incident.

Conclusion & Recommendations

The described scheme is highly indicative, encompassing numerous components and reflecting the specific features of attacks in the META region.

Key characteristics include:

- Government portals/websites, which are less protected against data breaches and hacking than banks, are used in the preparation phase of a social engineering attack;

- The fraudster impersonates an employee of a government agency and utilizes the victim’s real data, enabling them to quickly and effectively gain the victim’s trust;

- The attack is typically aimed at obtaining card details and OTP codes, eliminating the need for the fraudster to bypass security measures implemented in banking apps or websites;

- The operation is usually completed by cashing out the funds on local marketplaces or transferring them to a mule’s electronic wallet, helping to conceal the final recipient of the stolen funds.

Since the described scheme involves three agents targeted by fraudsters – a government portal, a financial institution (bank), and the owner of the bank account – our recommendations will be provided for each of them.

For Government Agencies:

- Protect users from account breaches and theft (monitoring leaks and notifying users);

- Implement account protection against ATO (Account Takeover) attacks – government websites and platforms are significantly less protected against ATO attacks than banking applications. This fact leads to a large amount of data potentially falling into the hands of fraudsters and being used later in social engineering attacks.

For Financial Institutions:

Group-IB’s Fraud Protection enables the detection of suspicious indicators at every stage of a fraudulent scheme’s development. Leveraging integration with Threat Intelligence, the solution monitors the activity of users whose data has been compromised—even on external domains like government portals—as soon as the stolen client information appears on the dark web.

The following are the main points to consider to minimize financial losses from the use of such schemes for financial institutions

General Recommendations:

- Establish robust anti-fraud processes by integrating session-based and transaction monitoring systems, provide clear instructions for response at all levels, ensure efficient handling of customer inquiries, and process confirmed fraud cases promptly and accurately.

In Terms of Usage of Antifraud Signals:

- On the first stage of implementation of the scheme (when the account has been leaked) Fraud Protection alerts are recommended for notifying users or combining with other logics to prevent fraudulent activity. These alerts can be integrated with transactional signals or other indicators of suspicious behaviour.

- When social engineering is used to attempt account access and manipulate users into taking specific actions, the system clearly highlights indicators of suspicious activity. Fraud Protection also enables the detection of active use or the presence of various Remote Access Tools (RATs) on a device, along with other warning signals, such as an active call during the customer’s session.

Fraud Protection Events at this stage can be used to forcefully terminate a user session, temporarily restrict the user, or transfer information to the transaction system as an additional indicator.

- Finally, during a 3-D Secure (3DS) operation, the system can detect uncharacteristic user behavior based on various parameters, such as network, behavioral, and suspicious activity related to information from another channel. Events can be used both for direct suspension/rejection of transactions and for transferring information to transaction systems.

For Group-IB customers: Please visit our Fraud Protection Intelligence portal for a more comprehensive report and detailed recommendations.

For customers and users:

From the perspective of protecting against identity theft:

- General digital hygiene rules regarding downloading unverified files and programs (primarily for Windows OS).

- Password managers, secure browsers, and so on.

From the perspective of protecting against social engineering attacks:

- Never share card details (or account credentials) with the so-called ‘employees’ over the phone;

- Avoid engaging in conversation with suspicious individuals during incoming calls; it’s better to call back using the official number;

- Bank employees will never ask you to install additional programs for assistance. At the slightest doubt about the legitimacy of a call, it is better to contact an organization or a bank directly using their official phone number.