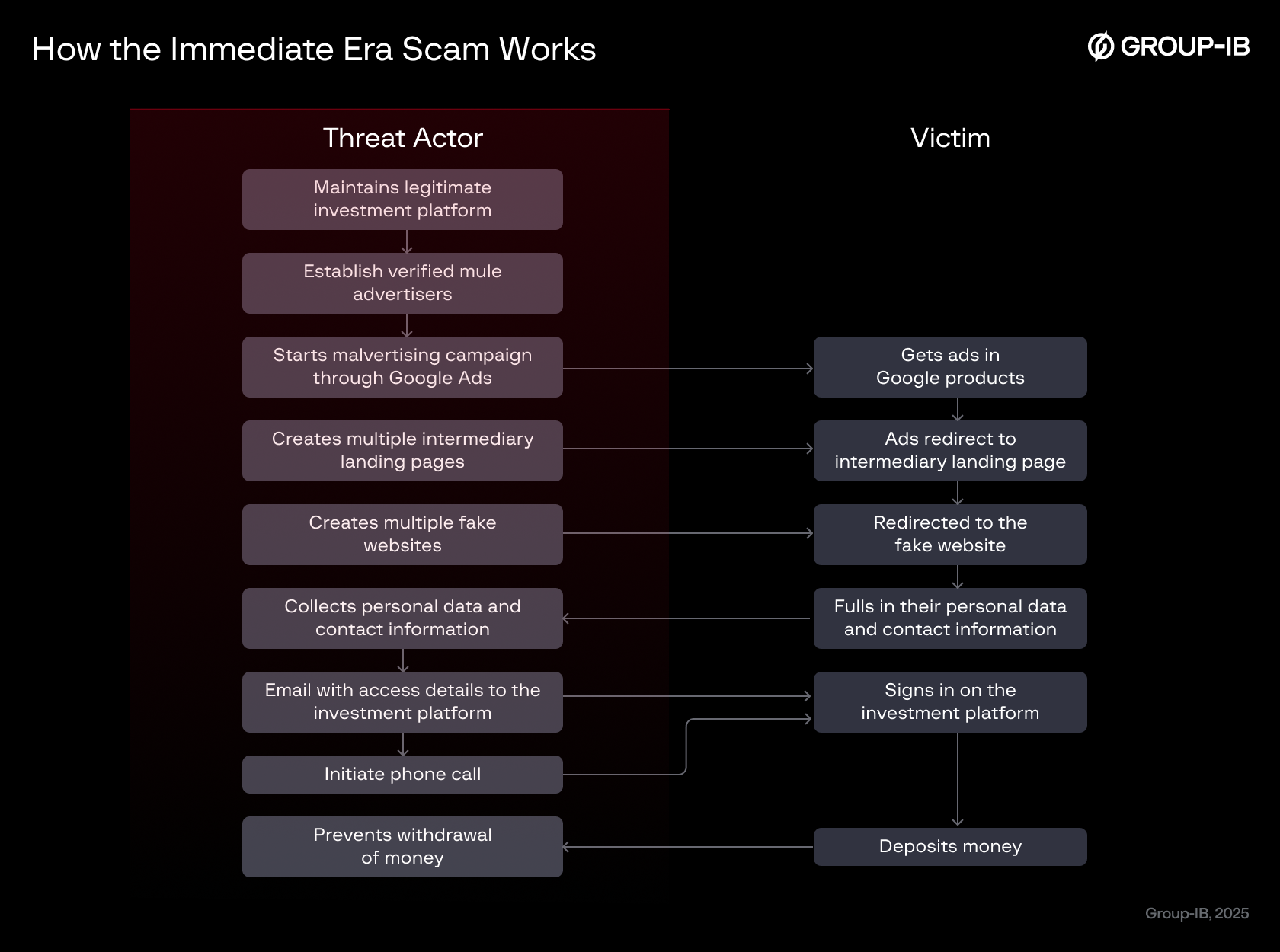

Introduction

Group-IB has identified a large-scale scam operation that misappropriate the images and likeness of Singapore officials, including Prime Minister Lawrence Wong and Coordinating Minister for National Security K. Shanmugam, to deceive Singapore citizens and residents into engaging with a fraudulent investment platform. The scam campaign relies on paid Google Ads, intermediary redirect websites designed to conceal fraudulent and malicious activity, and highly convincing fake webpages.

Group-IB’s analysis revealed that victims were ultimately directed to a forex investment platform registered in Mauritius, operating under a seemingly legitimate legal entity with an official investment license. This structure created an illusion of compliance while enabling cross-border fraudulent activity.

The operation’s sophistication highlights a high degree of organization among the perpetrators and demonstrates that traditional red flags are no longer sufficient for detection. Both investigators and everyday users must now assess scams holistically, considering technical, behavioral, and contextual indicators to identify deception effectively.

Key discoveries

- 28 verified advertiser accounts were used by fraudsters to run malicious Google Ads campaigns.

- These ads were configured to appear only to people searching or browsing from Singapore IP addresses, with ad copy and visuals tailored to Singapore residents.

- 52 intermediary domains were used as redirectors to conceal the final fraudulent destinations.

- 119 malicious domains impersonated legitimate and reputable mainstream news outlets to enhance the scam’s credibility.

Group-IB Threat Intelligence

Group-IB customers can access our Threat Intelligence portal for more information about this threat actor.

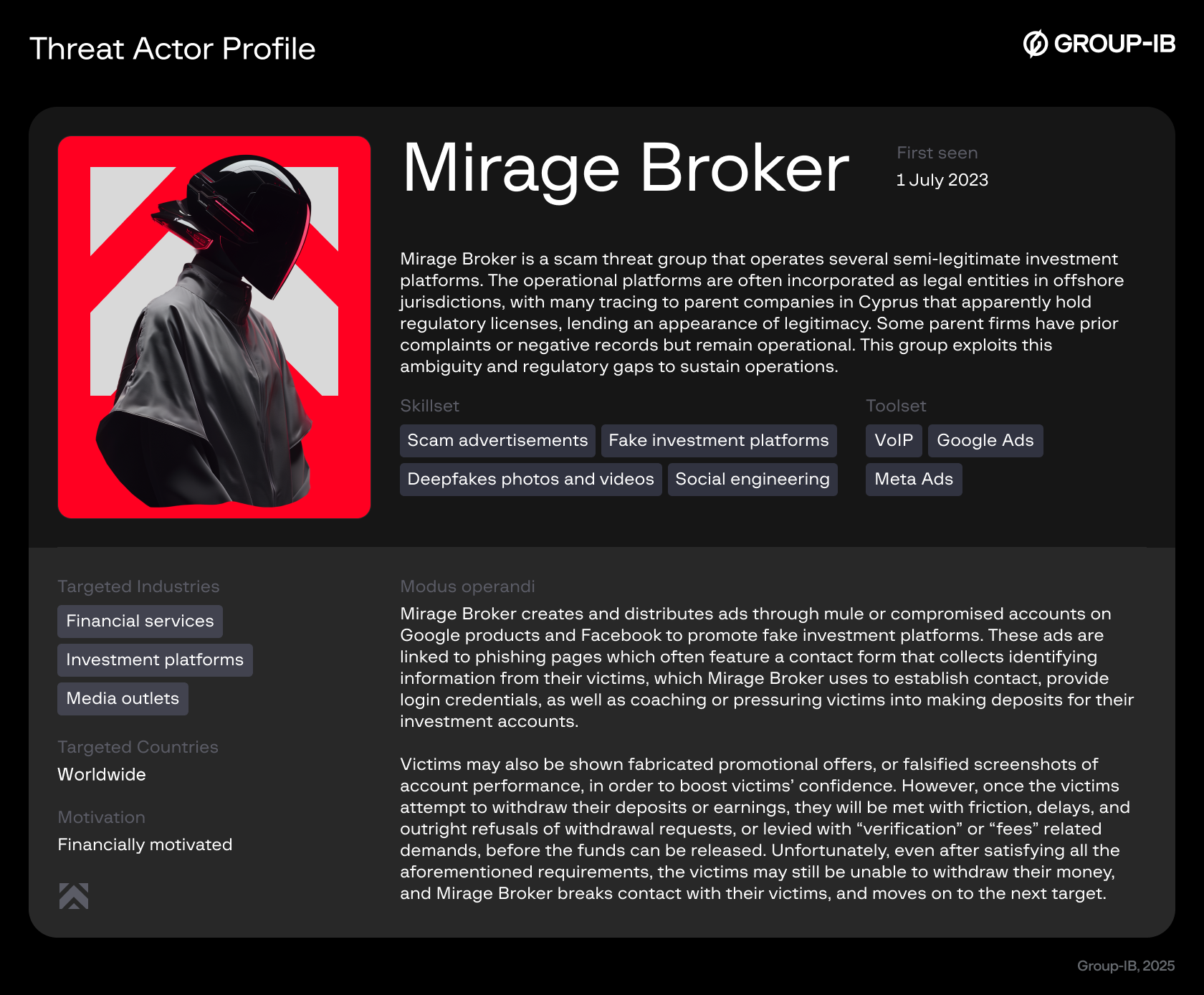

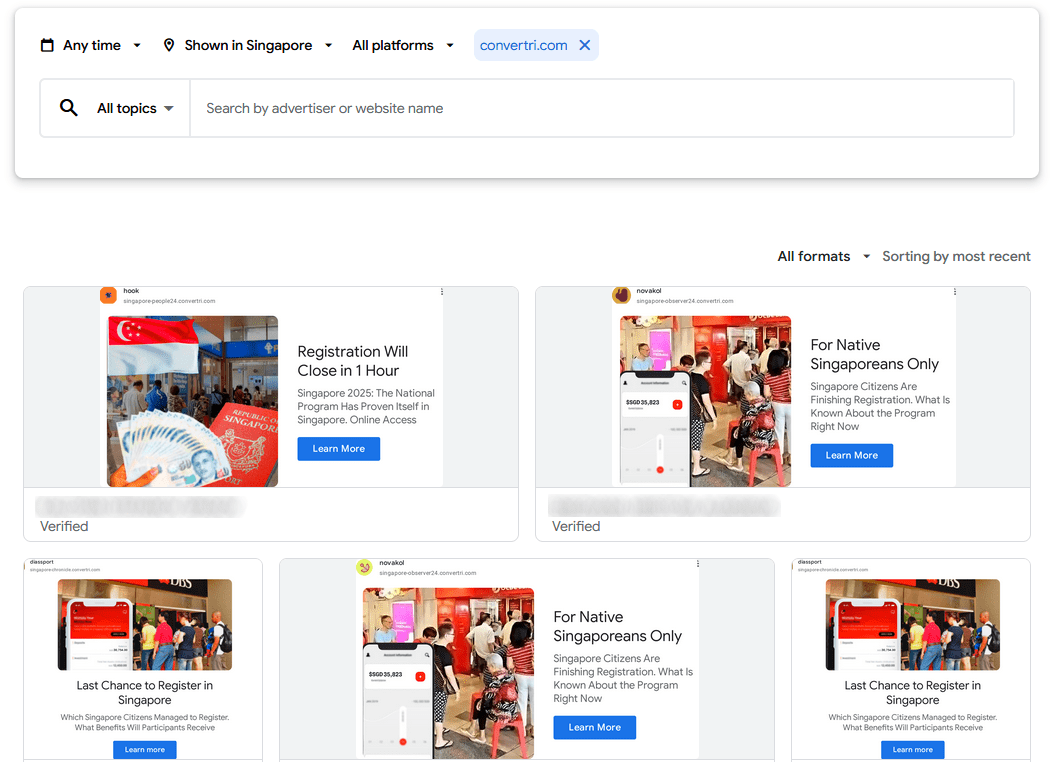

Verified Google Advertisements

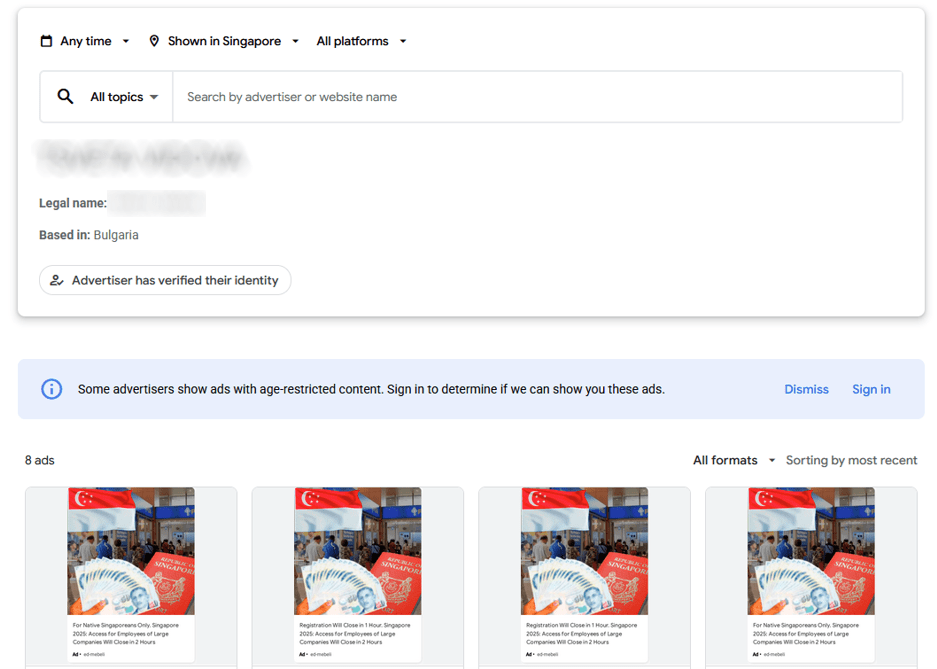

To attract potential victims, the scammers created numerous Google Ads specifically targeting Singaporean users and those residing in Singapore. While the Google Ads varied in appearance and style, they consistently promised lucrative investment returns for their victims.

Figure 1. A screenshot of several Google Ads that promoted the investment scam targeting Singaporeans and Singapore residents.

Google Ads appear across a wide range of Google services and platforms, includingGoogle Search, YouTube, Gmail, Google Maps (including the Maps app), Google Play, as well as within the Shopping tab. They are also displayed on millions of websites and mobile apps that are part of the Google Display Network, as well as on search partner sites affiliated with Google.

In this scam campaign, the ad distribution was managed primarily through verified advertiser accounts registered to individuals residing in Bulgaria, with additional accounts linked to Romania, Latvia, Argentina, and Kazakhstan.

Figure 2. A screenshot of an advertiser’s profile, with Google Ads associated with their account for the scam campaign.

It is worth noting becoming a verified advertiser requires completingGoogle’s verification process, which includes completing a questionnaire, linking a bank card, providing identification, verifying a phone number, and submitting a video selfie. While it is possible that some verified advertiser accounts may have been compromised, allowing to use remaining budgets to distribute malvertising, the consistent geographic patterns and the absence of other ads suggest that the fraudsters are likely using mule accounts created specifically for this campaign.

In total, 28 malicious advertisers were identified:

| Name | Country | Ads, total |

| Account 1 | Bulgaria | 1 |

| Account 2 | Bulgaria | 8 |

| Account 3 | Bulgaria | 2 |

| Account 4 | Bulgaria | 1 |

| Account 5 | Bulgaria | 2 |

| Account 6 | Bulgaria | 1 |

| Account 7 | Bulgaria | 1 |

| Account 8 | Latvia | 2 |

| Account 9 | Bulgaria | 1 |

| Account 10 | Romania | 4 |

| Account 11 | Bulgaria | 3 |

| Account 12 | Bulgaria | 9 |

| Account 13 | Bulgaria | 5 |

| Account 14 | Bulgaria | 9 |

| Account 15 | Bulgaria | 10 |

| Account 16 | Bulgaria | 6 |

| Account 17 | Bulgaria | 9 |

| Account 18 | Romania | 1 |

| Account 19 | Bulgaria | 1 |

| Account 20 | Kazakhstan | 1 |

| Account 21 | Bulgaria | 4 |

| Account 22 | Bulgaria | 3 |

| Account 23 | Bulgaria | 10 |

| Account 24 | Bulgaria | 6 |

| Account 25 | Bulgaria | 1 |

| Account 26 | Argentina | 10 |

| Account 27 | Bulgaria | 2 |

| Account 28 | Latvia | 2 (34 overall) |

Redirect Landing Pages

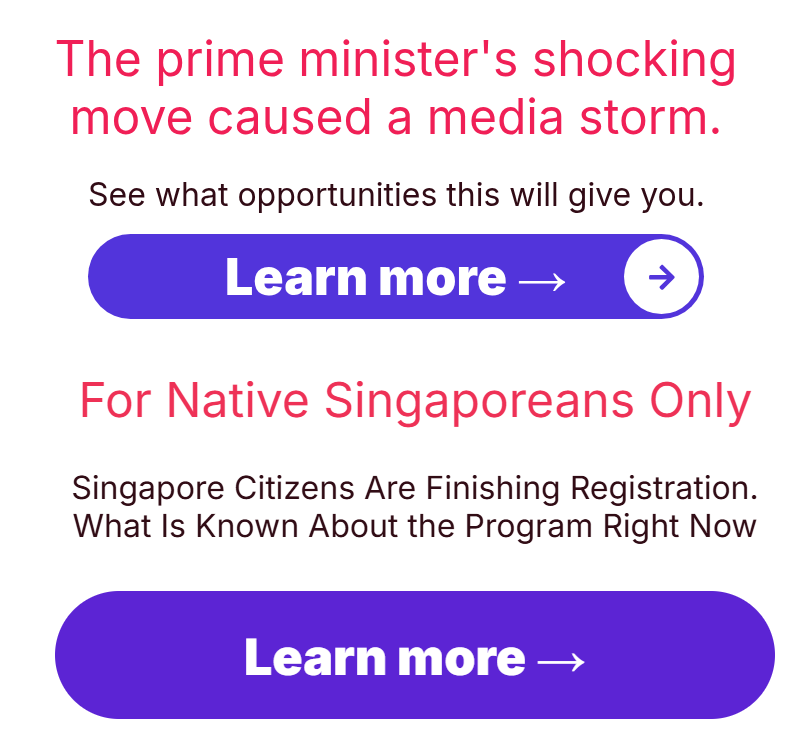

When a user clicks on the Google Ad promoting the scam, the ad redirects them to an intermediary landing page designed to conceal the final fraudulent site. These pages typically contain minimal text and a single call-to-action button that eventually forwards visitors to the scam site. This design and set-up is deliberately crafted to evade Google’s detection algorithms.

All intermediary pages are built with Convertri.com, a legitimate online platform for building high-conversion landing pages, sales funnels, and websites. The scammers exploited Convertri’s infrastructure, including its snowplow.convertri.com analytics endpoint, to host these lightweight redirect pages and collect basic visitor statistics while masking their true intent.

Figure 3. Two screenshots of the intermediary landing page where a brief statement and call-to-action button is shown.

Evading Detection by Government and Law Enforcement Agencies

After the redirect, victims are taken to fake news pages promoting the Immediate Era investment platform, which features fabricated endorsements and imagery of Singaporean political figures. Multiple variants of this platform exist online and appear to be operated by several different scam groups. However, Group-IB’s own analysis found no clear links between those variants and this specific scam campaign.

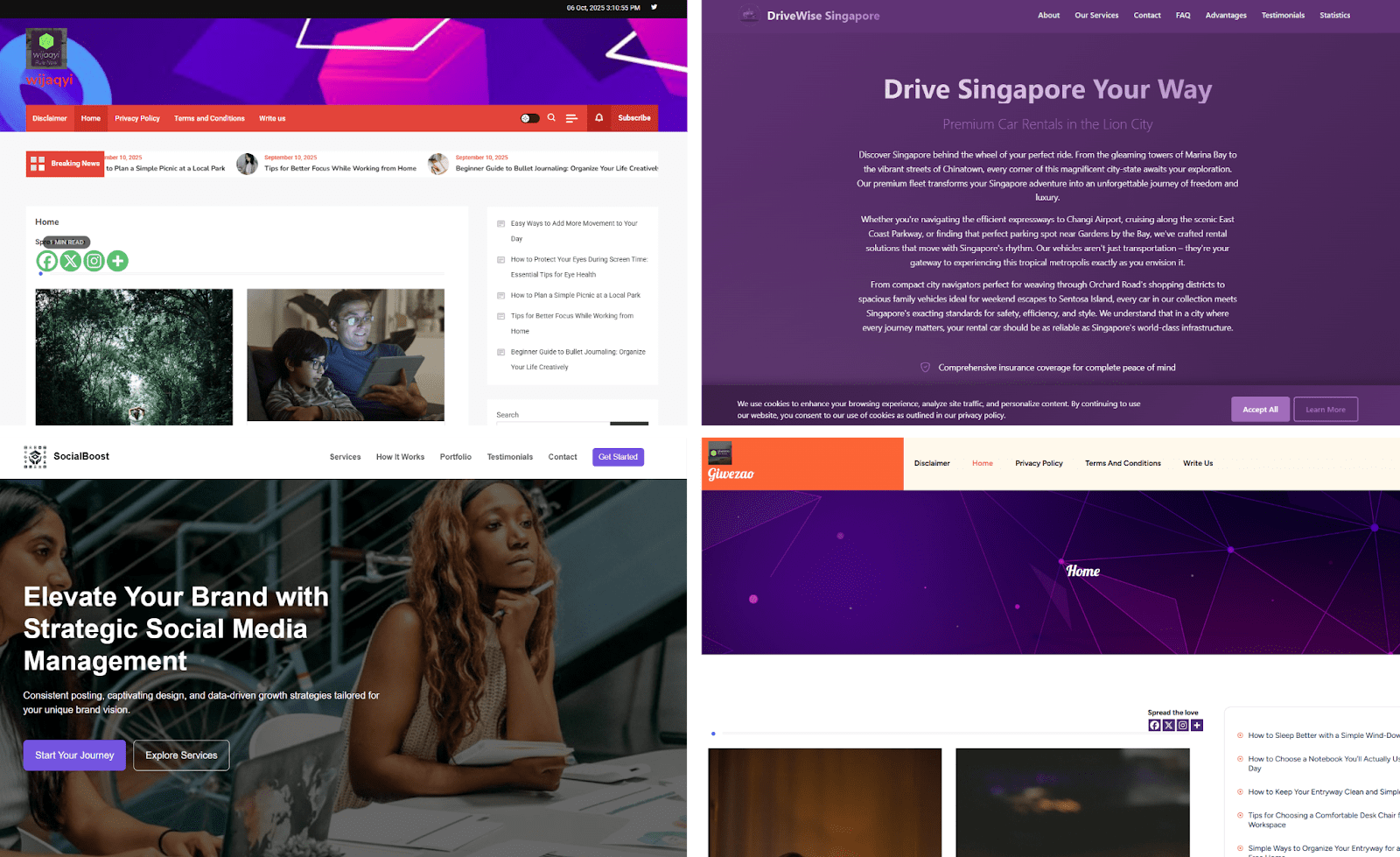

To evade detection by government agencies, law enforcement, and cybersecurity firms, the scammers employ a range of evasion techniques and reveal scam content only to likely victims. Visitors who do not meet the attackers’ targeting criteria are presented with a benign “secure” placeholder page instead of the fraudulent material.

Figure 4. A series of four screenshots of “secure landing pages” for visitors that did not meet the scammers’ target criteria, as a way of evading detection by government and law enforcement agencies.

During the course of the investigation, Group-IB identified the following evasion techniques used by the scammers:

- IP-range filtering: The pages allow access only fromIP addresses that resolve to Singapore and explicitly block known VPN and data‑center ranges, ensuring the scam is shown only to its intended local victims.

- Headless-browser and developer-tools detection: The site detects automated or instrumented browsing environments and hides content if such tools are present.

- URL / parameter gating: The scam content is revealed only when users arrive via a specific URL such as:

https://razudai.com/?campaignid=23048344702&creative=775205906157&gad_campaignid=23048344702&gad_source=1&gbraid=0AAAABBiO08-yHkIR2F8fDeVyrKVLoUdX6&gclid=CjwKCAjwlt7GBhAvEiwAKal0ckgQsBYVHv3peSPyghHHDwuXqaa9M9l1cMDi2_NT4XIbn3auETI4ohoC0jEQAvD_BwE&keyword&network=AL56F14D1V6-2-bh%C2%B6m1%3DrlepCLfx_Z8bEM-nu8RB%C2%B6m2%3D17591882703&placement&targetid=umz1r7366tgeph76yt9g&wbraid=Cj8KCQjwlt7GBhDnARIuAGZjSzMqETcuw2Wyx2xCAY72oun2AOBfSNYqUW-RRUKjmKklrPW__wU0YUp2IxoCkSU

The key parameter is targetid={ID} while other query parameters are incidental. The full list of parameters are as follows:

| URL parameter | Probable usage |

| campaignid | This parameter likely identifies a specific advertising campaign. It helps track which campaign generated the traffic. |

| creative | This possibly tracks the creative or specific Ad asset used within the campaign that the user clicked on. |

| gad_campaignid | This appears similar to campaignid, possibly a Google Ads campaign identifier, for tracking consistency within Google’s system. |

| gad_source | Likely denotes the source of the Ad click within Google’s ecosystem or tracking system. |

| gbraid | These parameters are used by Google Ads for tracking conversions and attribution on different platforms like web and app. They help Google connect the click to later actions. “gbraid” is often related to Google Ads conversion tracking (often for mobile app conversions), while “wbraid” is used for web conversion tracking through Google. |

| wbraid | |

| gclid | Google Click Identifier, a tracking parameter automatically appended to URLs when someone clicks on a Google Ad. It helps to track the click and link it with user behavior and conversion data. |

| keyword | This parameter would typically capture the keyword that triggered the ad. Here, it is empty but would usually carry that info. |

| network | Unknown. |

| placement | May be used to capture the placement of the ad (like website or app). |

| targetid | Possibly identifies the specific targeted audience or targeting segment for the Ad. The only parameter that is checked by the website to show scam content. |

Building Credibility Through Fabricated News Outlets and Imagery of Government Figures

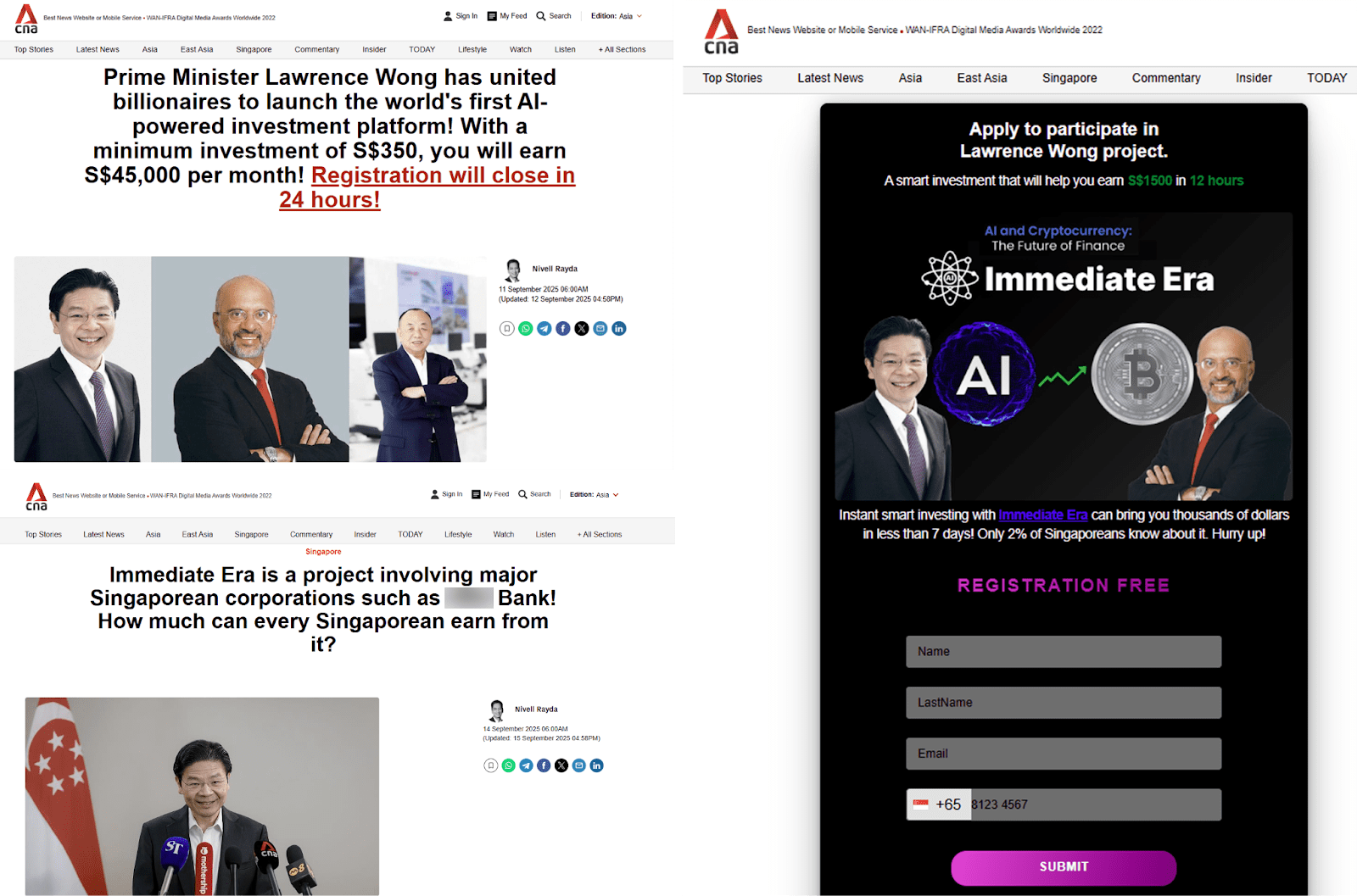

To lend credibility to the scam, the fraudsters also prepared factitious news sites that replicate the look, design and layout of legitimate news outlets. During Group-IB’s investigation, we found two primary scam scenarios:

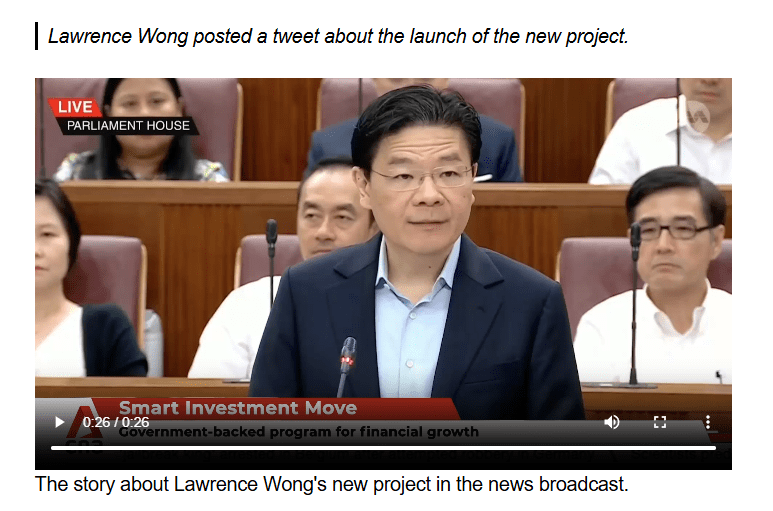

- CNA Impersonation: A fraudulent site posing as CNA (Channel NewsAsia) features a deepfake video of Prime Minister Lawrence Wong endorsing the “Immediate Era” investment program, and prompts visitors to submit their contact details to join the “program”. Another fake CNA article appeared to be written by a current CNA journalist based in Indonesia.

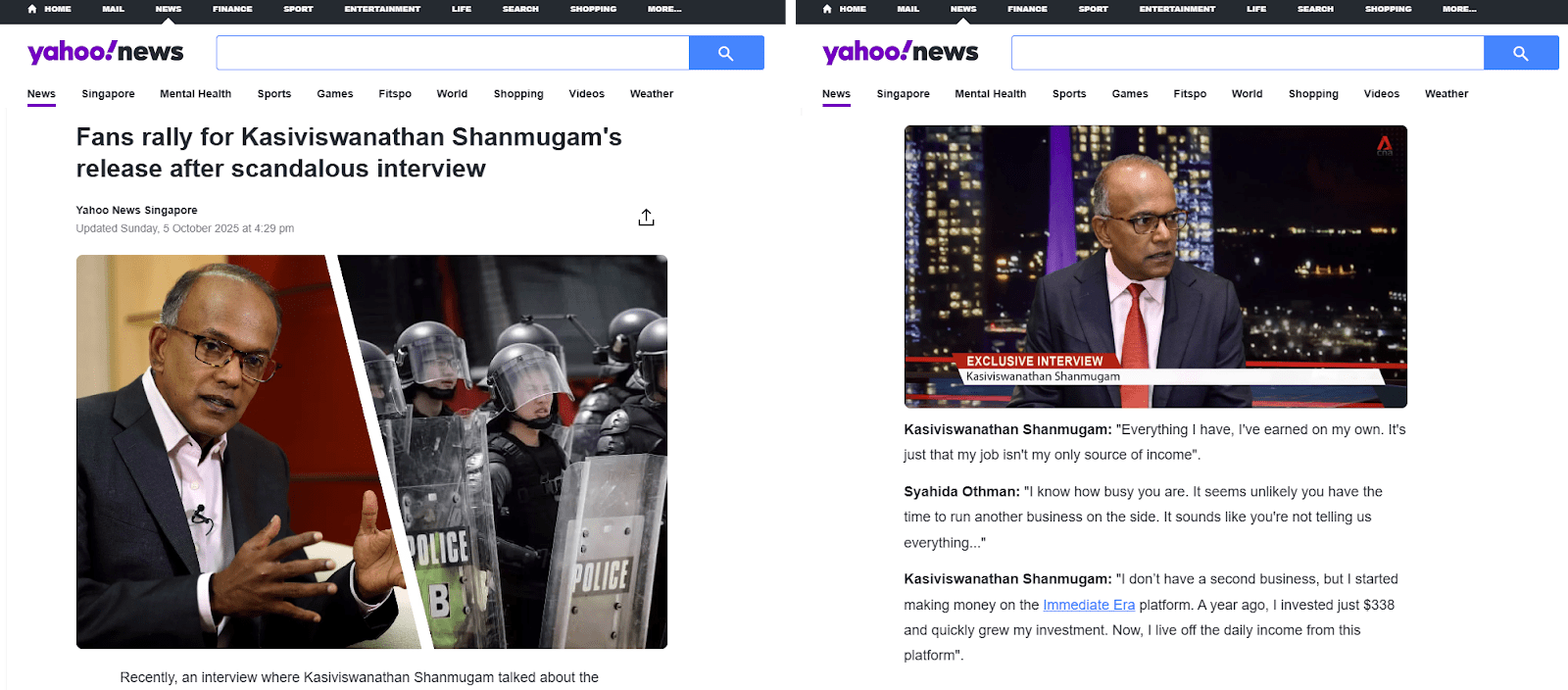

- Yahoo! News impersonation: A fake Yahoo! News page publishes a fabricated interview with Coordinating Minister for National Security, K. Shanmugam that insinuates the minister’s wealth came from the “Immediate Era” platform. This page keeps users on the same domain and redirects them to the site’s “Immediate Era” section, where contact details are collected.

Both variants rely on fabricated credibility, using impersonated media and high-profile Singapore officials, to harvest contact details for aggressive follow-up solicitation.

Figure 5. (Left top and bottom) Screenshots of the fake news site that showed prominent public figures endorsing the “Immediate Era” investment plan, with the article itself seemingly authored by a current CNA journalist. (Right) The fake news site also features a page where victims could sign-up for the “Immediate Era” program.

Figure 6. A screenshot of a deepfake video created by AI of the Lawrence Wong, Prime Minister of Singapore, endorsing the “Immediate Era” program in parliament.

Figure 7. Screenshots of a fictitious interview with Coordinating Minister for National Security, K. Shanmugam that insinuates the minister’s wealth came from the “Immediate Era” platform.

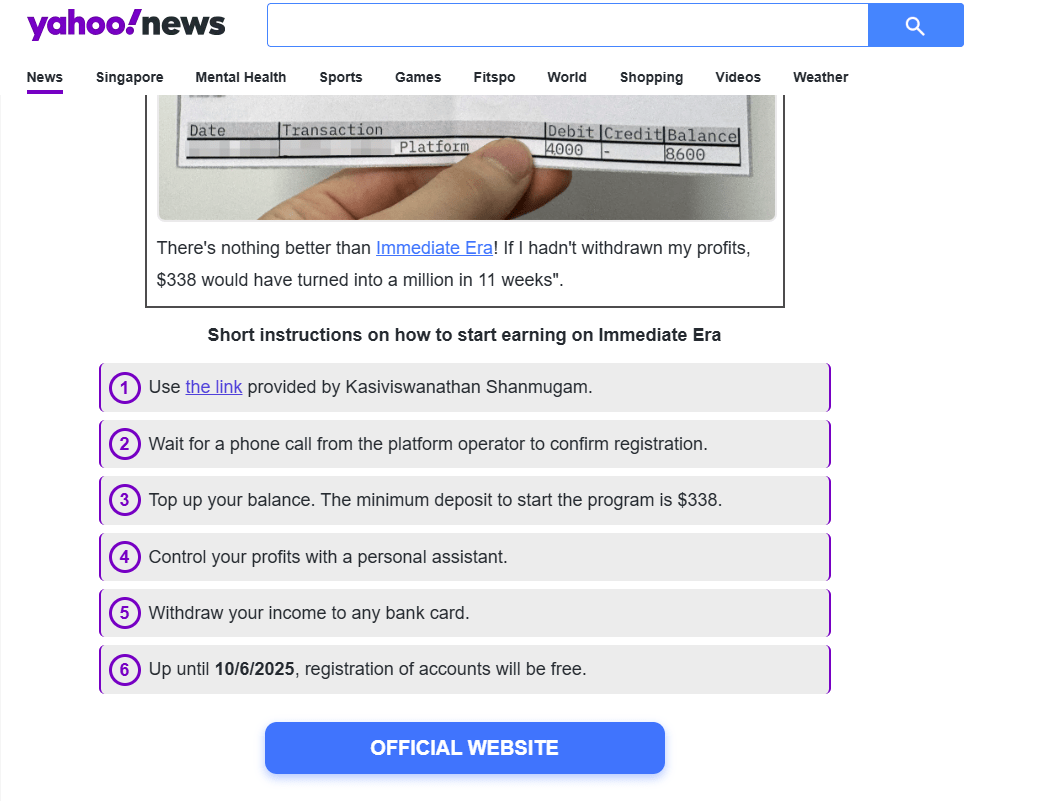

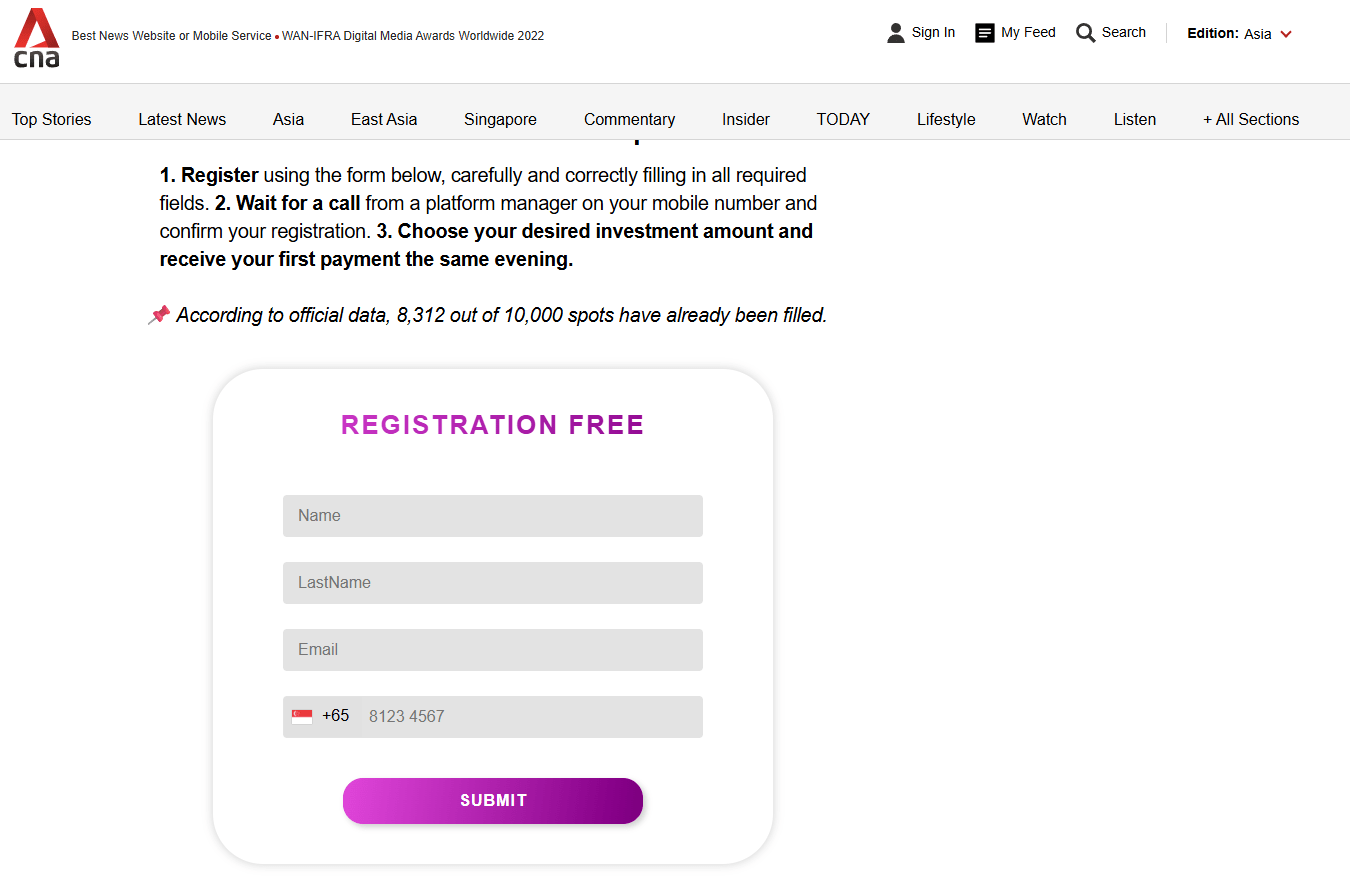

Figure 8. The site also features instructions on how to users could get involved with the “Immediate Era” program.

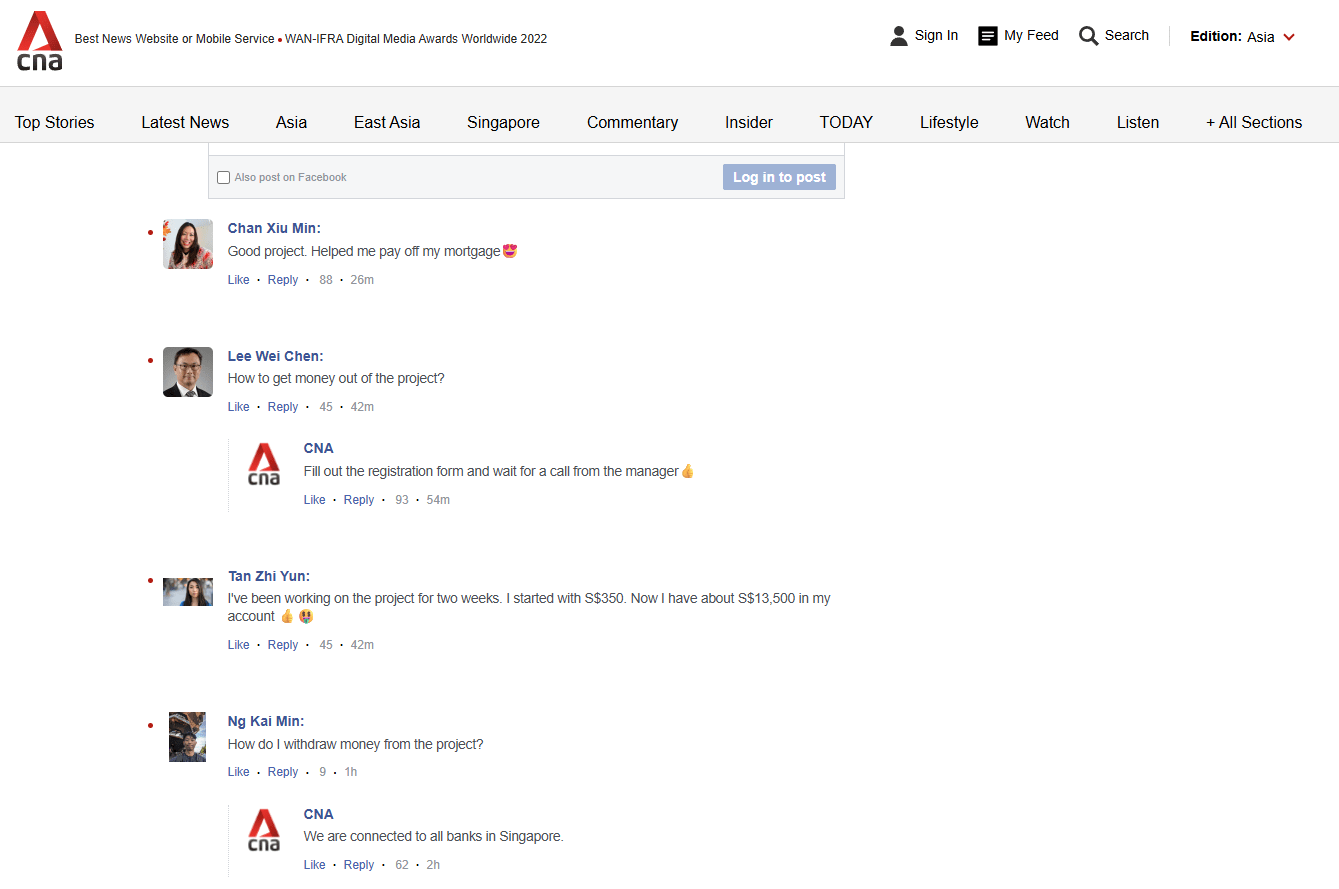

Figure 9. Fabricated comments on the fake media outlet website.

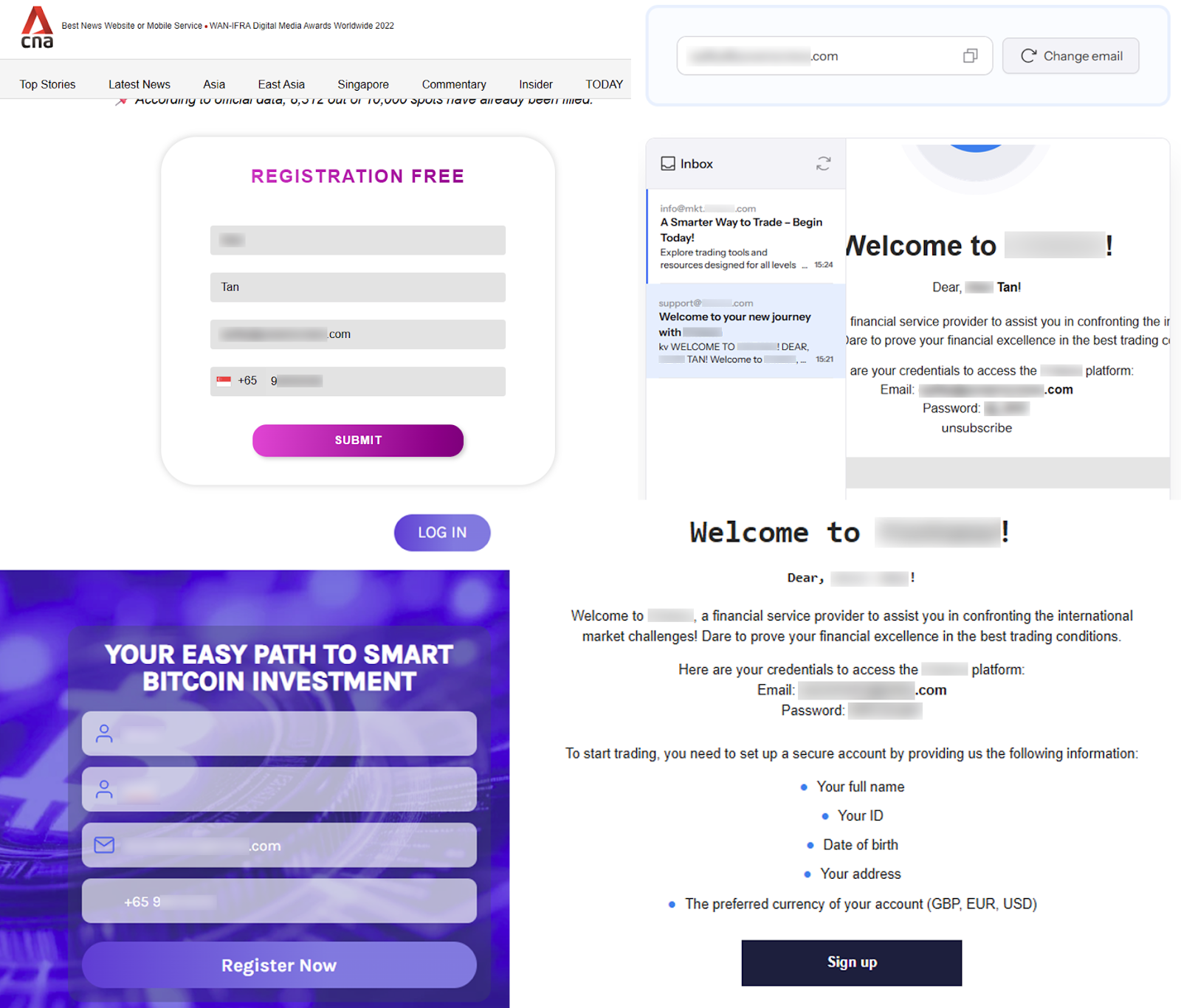

The scammers’ goal at this stage is to collect contact information from their victims, and subsequently communicate with them via phone or email.

Figure 10. The registration page designed to collect potential victim contact information, while creating a sense of urgency.

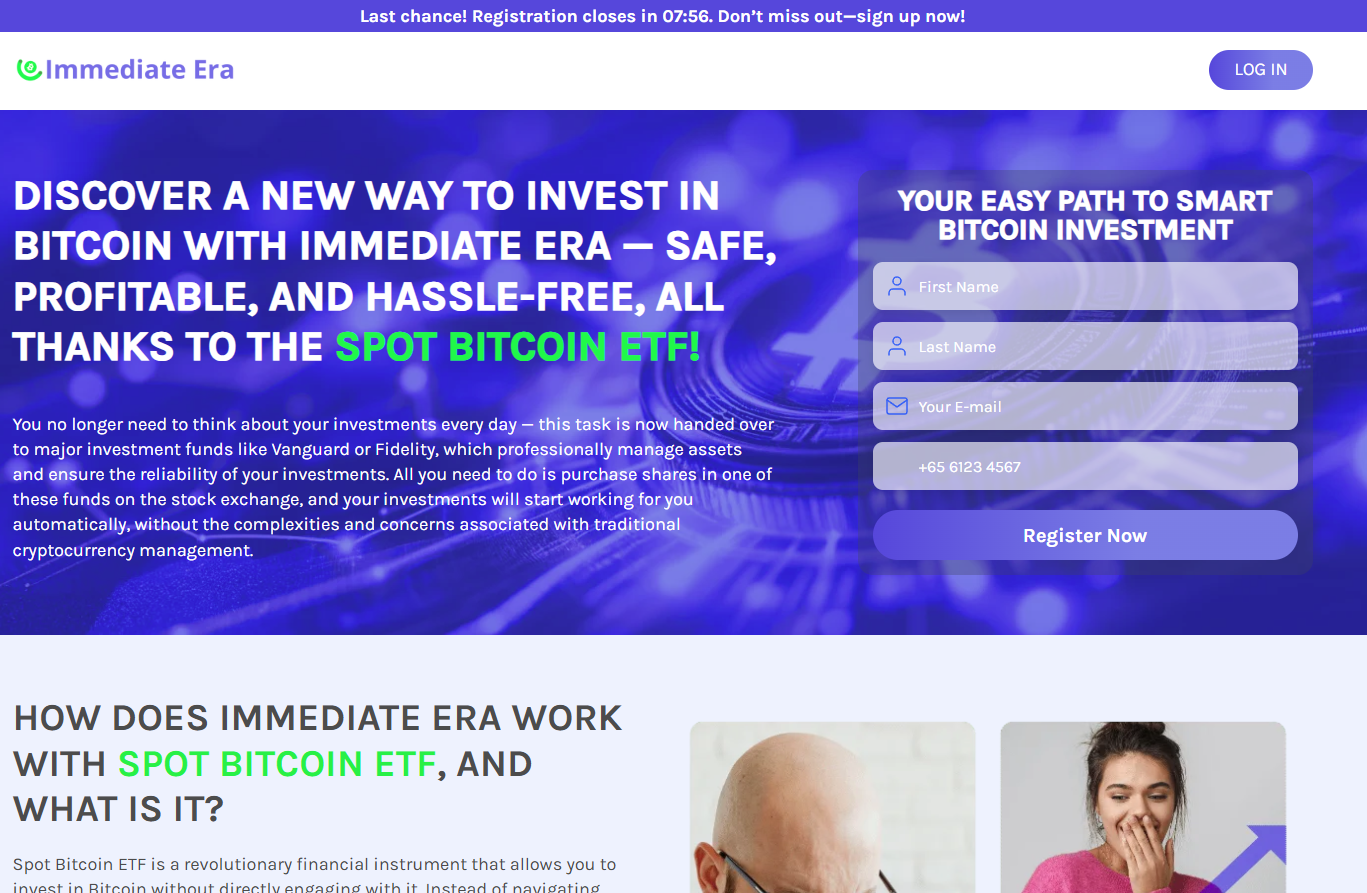

Figure 11. The registration page on the fake landing page of the “Immediate Era” investment scam platform.

Investment platform

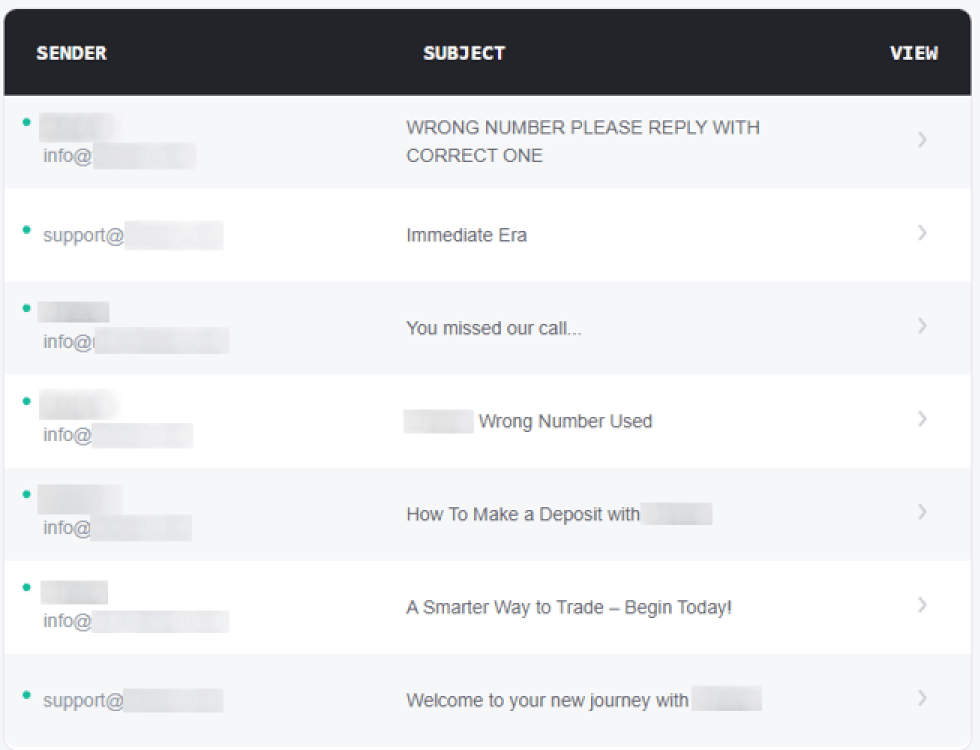

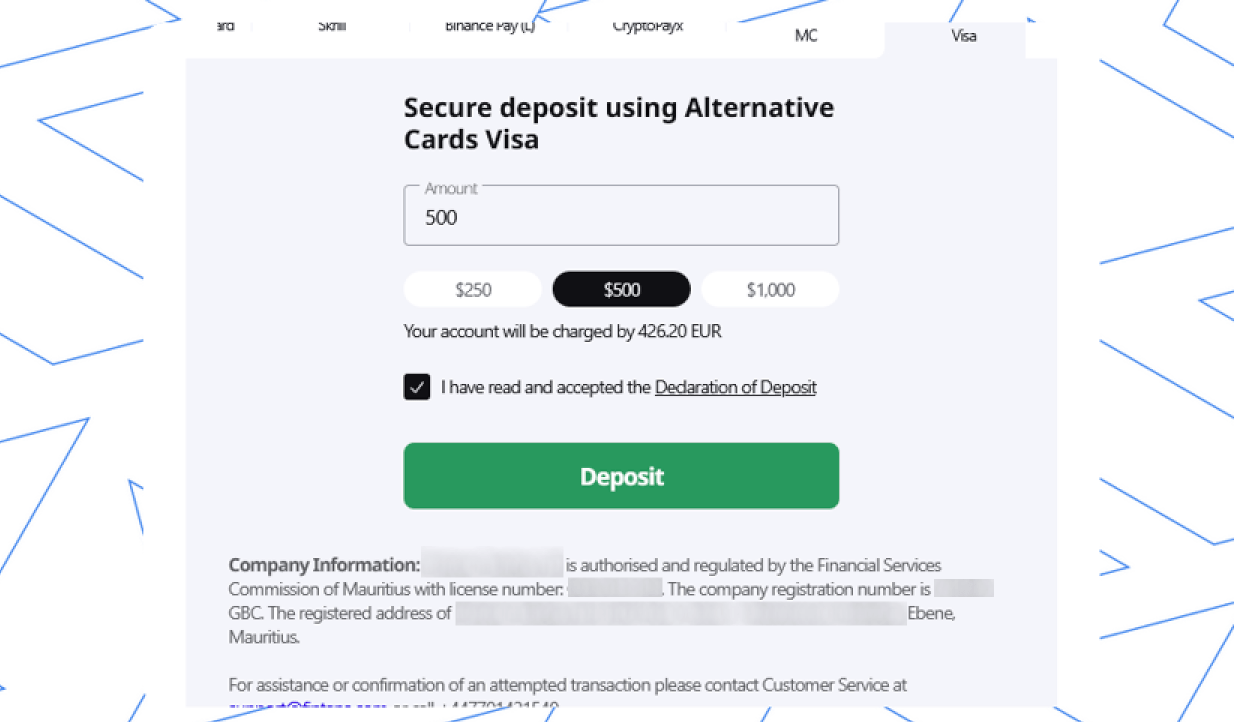

Regardless of the scam variation, once the victim submits their personal information, they will receive an email containing login credentials for the investment platform that doesn’t have any mentions of “Immediate Era” program. On that platform, users are aggressively pressured, typically via telephone calls, to deposit substantial sums of money deposits, while any attempts to withdraw funds is met with significant resistance. Withdrawals are systematically delayed or denied under seemingly legitimate pretenses, such as requests for identity verification or additional documentation, which are then rejected under various pretexts or followed by further bureaucratic demands.

In addition to difficulties with withdrawals, the platform’s terms of use imply fairly high transaction fees and also encourage constant deposits. The platform requires a minimum deposit of US$250 or its equivalent in other accepted currencies to open an account.

In addition, the platform imposes other fees such as:

- US$30 for bank withdrawals

- Inactivity fees ranging from US$100 to US$500, depending on inactivity duration.

Figure 12. Forms that collect contact information, and the emails that victims would receive after providing their contact information.

If users do not provide a valid phone number, platform representatives will persistently attempt to move the conversation to a phone call.

Figure 13. Platform representatives will persistently try to get the users to provide a valid telephone number in order to move the conversation to a telephone call.

Figure 14. A screenshot of the interface on the platform for adding deposits.

Our investigations show that at least 3,808 Singaporean users clicked ads and were redirected to intermediary sites in the past month. Based on our estimates, 18% (685 people) were then forwarded to malicious sites and remained there. The fraudulent platform itself has more than 2,000 visitors per month globally.

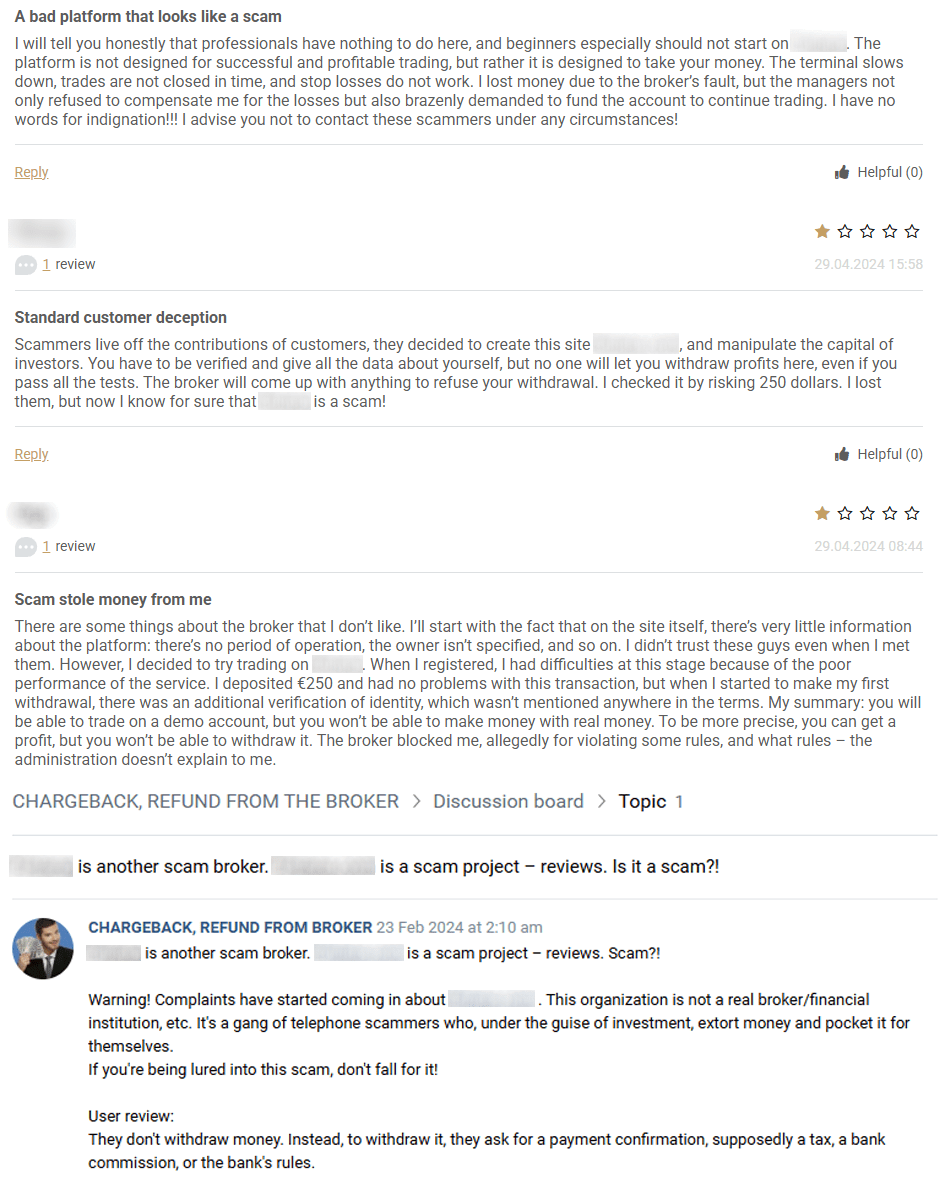

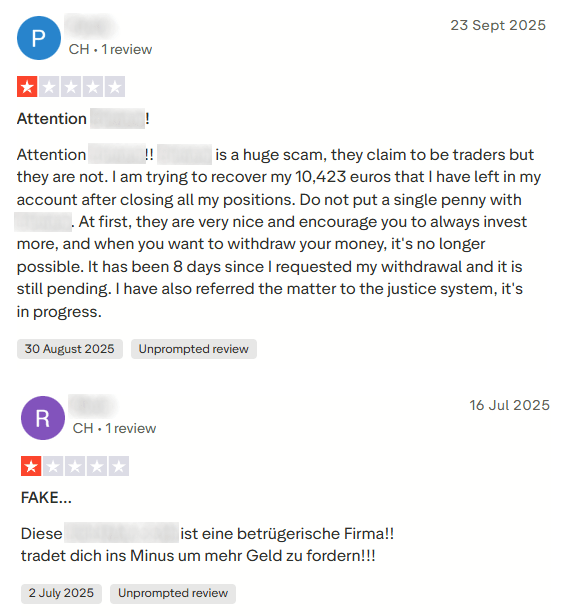

It should be noted that the platform is actually a Mauritius-registered forex broker operating licensed by the Mauritius Financial Services Commission (FSC). Platform also claims affiliation with Cyprus-based parent company regulated by the Cyprus Securities and Exchange Commission(CySEC).

Mauritius is not considered a top-tier regulatory jurisdiction for major international finance. However a formal registration and license lend an appearance of legitimacy to the operation This perceived legitimacy increases the likelihood that victims and intermediaries will trust the platform and overlook other red flags. Scammers exploit that trust to pressure users into making deposits while obstructing or preventing withdrawals.

Despite its licensing, the company has a documented history of legal and regulatory issues. The Cyprus Securities and Exchange Commission (CySEC) temporarily suspended licence of the alleged parent company multiple times citing concerns about compliance and capital adequacy. Recent reports suggest that the parent company is currently inactive, with the most recent online reviews dating back to 2021. Their authorisation in the UK was also revoked in 2022.

User reports further describe aggressive telephone solicitation and persistent withdrawal difficulties, sometimes rendering withdrawals effectively impossible.

Figure 15. Screenshots of negative user reviews of the platform.

Figure 16. Screenshots of user reviews of platform, calling it a scam.

According to historical WHOIS data, platform earlier was owned by a lead generation service that collected consumer contact information by offering free and discounted products to visitors. The website encouraged visitors to complete travel-related survey questions, such as “Select your favorite travel destination”, on online forms. They then sold the collected phone numbers to telemarketing companies.

However, they failed to clearly disclose that providing their information, consumers would receive telemarketing calls from third parties. In 2009, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) determined that service’s practices contributed to $1.2 million in civil penalties imposed on the companies that used their lead generation services. The companies that purchased consumer data were found to have violated the Telemarketing Sales Rule by calling consumers on the Do Not Call Registry (DNC) without proper authorization.

This history suggests that the operators possess established expertise in large‑scale data collection and telemarketing, capabilities they appear to have repurpose in the current scam through aggressive phone solicitation and sustained pressure on victims to make deposit.

Conclusion

Group-IB’s investigation into the Immediate Era scam highlights the increasing sophistication and cross-border coordination of financial fraud operations targeting Singaporean citizens. By combining verified Google Ads, fake media outlets, and deepfake technology, scammers have built a multilayered deception ecosystem that mimics legitimate financial services and leverages apparent regulatory compliance to gain victims’ trust.

The use of a formally registered investment platform demonstrates how scammers exploit weaker jurisdictions to create an illusion of authenticity. Their reliance on aggressive telemarketing, data harvesting, and bureaucratic obstruction to block withdrawals reflects a professionalized fraud infrastructure with roots in prior lead-generation and telemarketing schemes.

This case underscores a broader trend: modern scams are no longer easily identifiable through superficial red flags. They employ advanced targeting, verified ad networks, and convincing branding to bypass conventional security and user awareness measures.

Recommendations

- Be skeptical of unsolicited investment opportunities. Treat any advertisement or messages that promise unusually high returns, especially those featuring public figures. Scammers often use images of officials to lend false credibility.

- Verify information independently. Do not solely rely on the information presented in advertisements or on landing pages. Always verify the legitimacy of investment platforms, news outlets, and claims made by individuals. Look for independent reviews, but filter out overly positive reviews and pay attention to negative ones as positive reviews could be created by bots. Check for any history of legal problems or license suspensions, even if they claim to be regulated.

- Look beyond obvious indicators of maliciousness. Scammers are becoming more sophisticated. Even if a platform appears legitimate with registrations and licenses, evaluate it holistically. Look for other red flags, such as misspelled domains, web pages that lack functionality, aggressive solicitation tactics.

- Exercise caution with redirect pages. Be suspicious of links that redirect you through multiple pages before reaching a final destination. Scammers use these to evade detection.

- Protect your contact information. Be cautious about providing your contact details, especially phone numbers, on unfamiliar websites. Scammers use this information for aggressive follow-up communication.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Immediate Era scam?

The Immediate Era scam is a large-scale fraudulent investment scheme that targets Singaporean citizens. It promotes a fake investment platform through paid Google Ads, deepfake videos, and impersonated news websites featuring well-known Singaporean political figures. Victims are redirected through a chain of deceptive landing pages to a fraudulent trading site designed to collect their personal information and money.

How are victims targeted?

Victims typically encounter the scam through Google advertisements that appear on platforms such as Google Search, YouTube, Gmail, and Maps. These ads promise high-return investment opportunities supposedly endorsed by government officials. Clicking the ads directs users to fake news articles or interview pages, where they are urged to register with their personal details.

What happens after victims submit their details?

After completing the registration form, victims receive an email with login credentials for the platform, a fraudulent forex investment platform. Once on the platform, users are aggressively pressured—usually by phone—to make deposits. Withdrawals are then delayed or denied under false pretenses, often through excessive identity verification demands or other fabricated administrative obstacles.

What warning signs should users look out for?

Warning signs of such scams include investment offers that promise unusually high returns with little or no risk, the use of celebrity or political endorsements—particularly featuring local officials—to create false credibility, domains that imitate legitimate news or government websites, aggressive phone calls pressuring victims to make immediate deposits, and persistent difficulties or delays when attempting to withdraw funds.