Introduction

In the dark corners of the internet, countless individuals claim to be cybercriminals responsible for massive breaches and sensitive data leaks. These self-proclaimed threat actors often boast about hacking major corporations resulting in compromising internal resources (accesses, documents, source codes, databases, personal data and much more)—actions that inevitably attract the attention of the media, researchers, analysts and cybersecurity experts.

In reality, many of these claims are completely false. A significant number of “threat actors” are not hackers at all—but scammers who never conducted an attack, provided fabricated evidence or old data, and misled the public, capitalizing on public fear and the cybersecurity community’s eagerness to uncover the next big breach.

In this blog, we will:

- Shed light on common examples of fraudulent techniques used by scammers

- Showcase specific examples where these techniques have been used

- Identify the platforms where these scammers operate most frequently

- Provide indicators that help differentiate real threat actors from fraudsters

Disclaimer:

Please note that throughout this article, the names of companies affected by fraudsters—as well as those whose leaked databases were misused to fabricate evidence—will be intentionally omitted. Additionally, any visual samples containing user data that could reveal the true source of the information claimed to be “fresh” by the attackers will not be displayed.

How to Detect a Dark Web Scam: Main Indicators

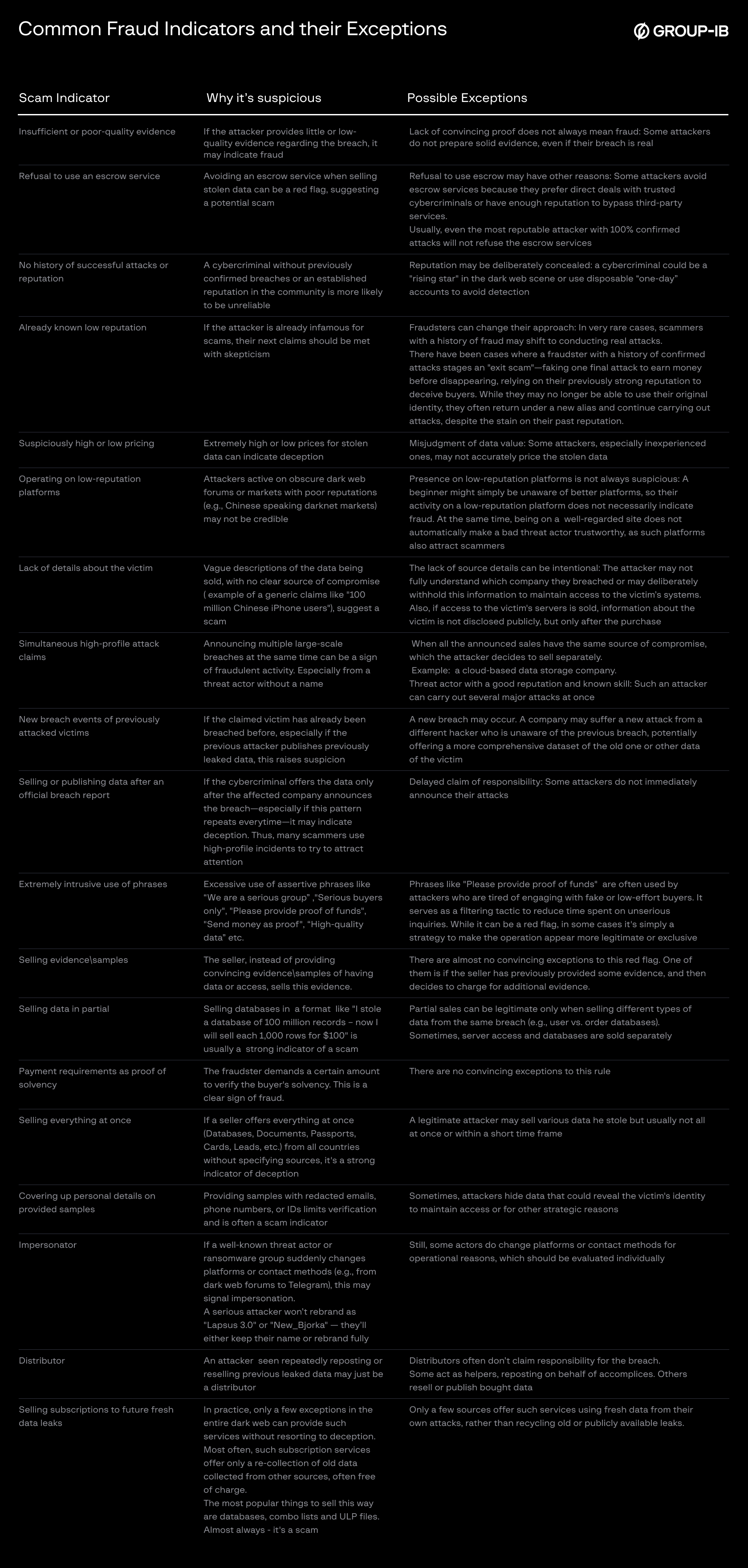

While each case should be evaluated individually, there are several recurring factors that often signal deception by the scammer. The table in figure 1 is a summary of common fraud indicators and their exceptions:

Figure 1: Summary of common fraud indicators and their exceptions

Even cybercriminals with a solid reputation, a history of confirmed attacks, sales, or leaks can still intentionally resort to deception—particularly in “Exitscams” where they disappear after a final, high value scam. Others may misrepresent recycled or misattributed data or access. That’s why, each case must be analyzed individually in a context, with careful eye on how many red flags show up. The more indicators present, the more confident we can conduct preliminary conclusions that a scam exists about any breach claim, and in some cases give 100% certainty that the attacker is a fraudster – without examining any evidence.

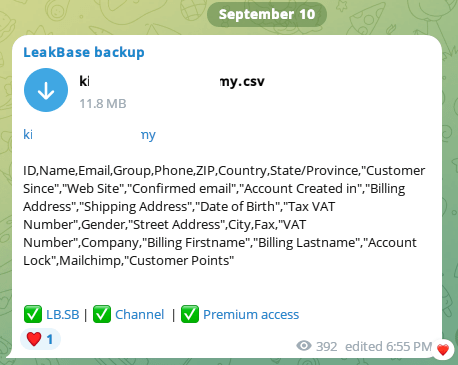

Lastly, on “paid” users or “premium” accounts: these mean very little. Some experts and researchers mistakenly treat them as signs of legitimacy , but in reality scammers can easily afford “premium” access for a small fee.It’s not a credibility badge—just a tactic to appear more trustworthy.

Where Scammers Operates in the Dark Web:

- Chinese-speaking dark web marketplaces

- Chinese-speaking scam-prone Telegram channels

- Hacktivists

- Impersonators

- Scam-Prone Telegram Channels

- Dark web forum scammers

- Distributors & ReCollectors

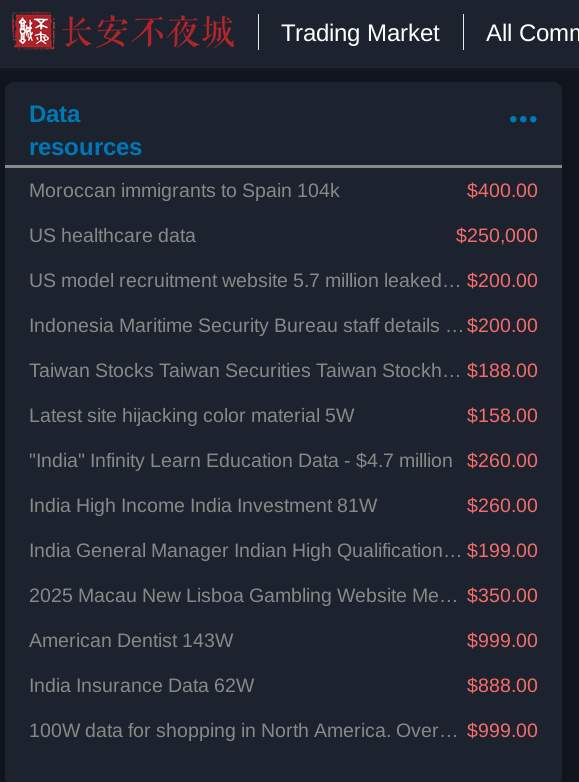

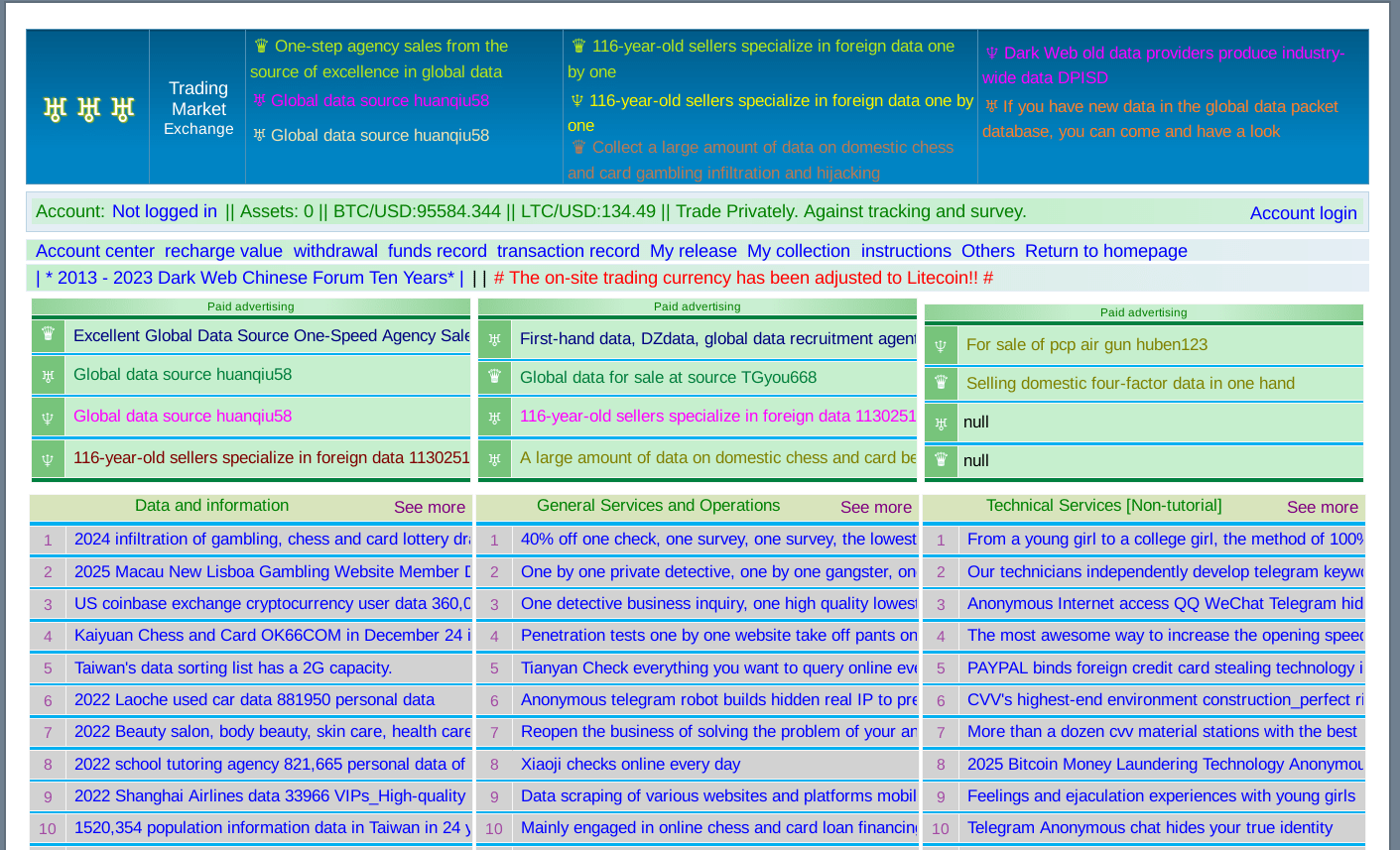

1. Chinese-Speaking Dark Web Marketplaces

Level of Reliability and Credibility – Close to Zero.

Various Chinese-speaking dark web marketplaces like “Chang’An Sleepless Night” and “Exchange Market” are mostly well-known for their flashy listings and untraceable user IDs. But they follow a model that all but guarantees fraud:

- Buyers and sellers never interact directly

- Listings lack verifiable samples

- Transactions are completed automatically through download links

What’s being mainly sold are often:

- Old data from public leaks

- Freely available info repackaged as “fresh”

- Fake or autogenerated records

As a result of these key features: Nearly 100% of the data sold here is a scam — it has nothing to do with any real breach. Instead, these marketplaces are filled with fake data, old public leaks, resale of previously sold data obtained as a result of old attacks or purchased from b2b companies, or freely available information.

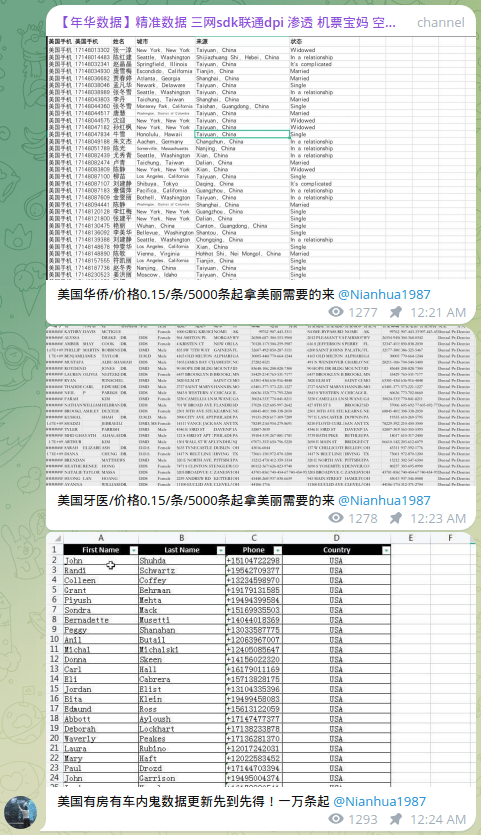

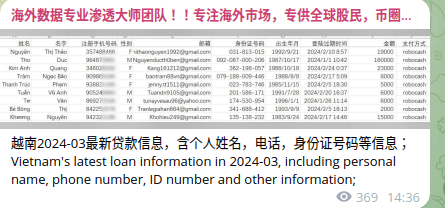

2. Chinese-Speaking Scam-Prone Telegram Channels

Level of Reliability and Credibility – Close to Zero.

Very similar to Chinese-speaking dark web markets, there are platforms that cannot carry out any actual attacks and offer nothing more than fake or recycled old public data for sale or download. These platforms typically rely on deceptive tactics to create the illusion of access to fresh data, but in reality, they provide either old leaks or data from public sources with no real connection to a legitimate attack. These channels pop up daily and are frequently banned, only to be replaced by nearly identical clones.

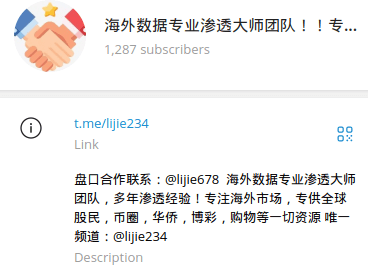

One notable example is 海外数据专业渗透大师团队-@lijie234 (Overseas data professional penetration master team), a Telegram channel that claims to sell global customer databases. Upon inspection by Group-IB analysts, the data it offers is consistently pulled from old leaks previously posted by other actors — often for free.

Figure 4 shows @lijie234 channel’s description translated below:

Contact for market cooperation: @lijie678 Overseas data professional penetration master team, many years of penetration experience! Focus on overseas markets, dedicated to global stock investors, currency circles, overseas Chinese, gambling, shopping and other resources. Only channel: @lijie234

Figure 4: @lijie234 channel description

3. Hacktivists

Level of Reliability and Credibility – Close to zero for the vast majority, with some exceptions.

Hacktivism—a combination of “hacking” and “activism”—refers to hacker activity carried out for political, ideological or social motivations. Unlike traditional cybercriminals, hacktivists often don’t seek financial gain. Instead, their goal is visibility.

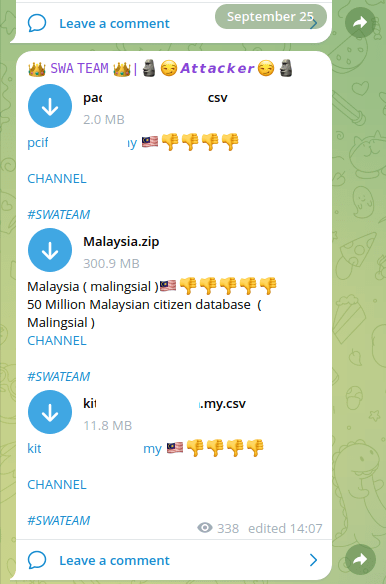

While some hacktivists may perform low-level attacks (e.g., DDoS, website defacement, or accessing low-security accounts via publicly available stealer logs), their more sensational claims—such as stealing vast databases—are almost always fraudulent. They will often use provocative language to attract media and researcher attention, bold headlines: “50M Malaysian citizens leaked!” that often cite outdated breaches, false attribution of data originally leaked by others, and recycling of public or stolen info to build a false image of legitimacy.

By 2025, Telegram has become the primary platform for hacktivist activity, though many still maintain a presence on dark web forums and social media (such as X/Twitter).

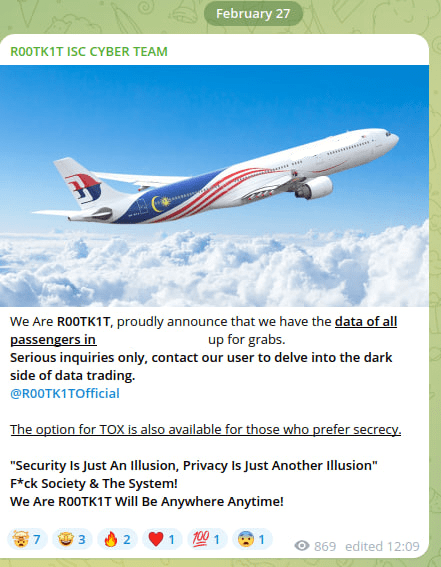

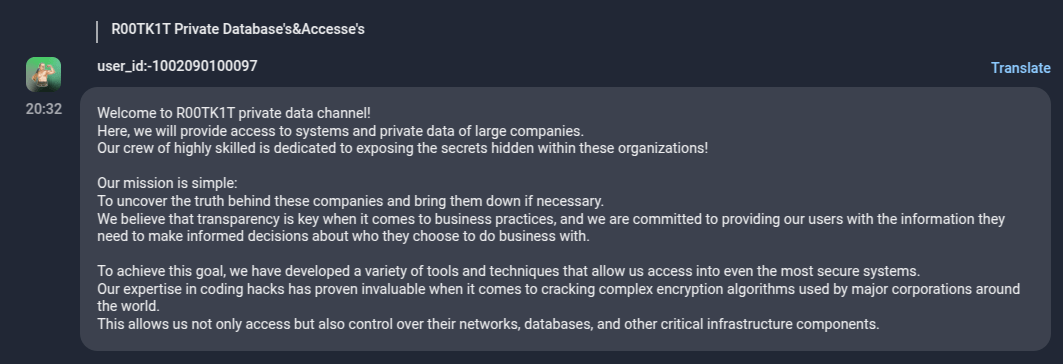

Case Study: The R00TK1T Path of Deception

One of the most prominent examples of hacktivist deception is the group R00TK1T, which managed to gain significant media attention by claiming responsibility for attacks on major global corporations following this main strategy:

- Early access to some accounts from government institutions or companies using publicly available credentials from stealer logs

- Simultaneously, R00TK1T made false claims about additional breaches and data leaks — without offering any evidence

- Media coverage and hype built a reputation for the group, despite the lack of verification

Eventually, the group began selling access to so-called “breached data” including:

- Data allegedly stolen from 10 Malaysian companies (priced at $50,000 each)

- Passenger records from a Malaysian airline (offered for $40,000)

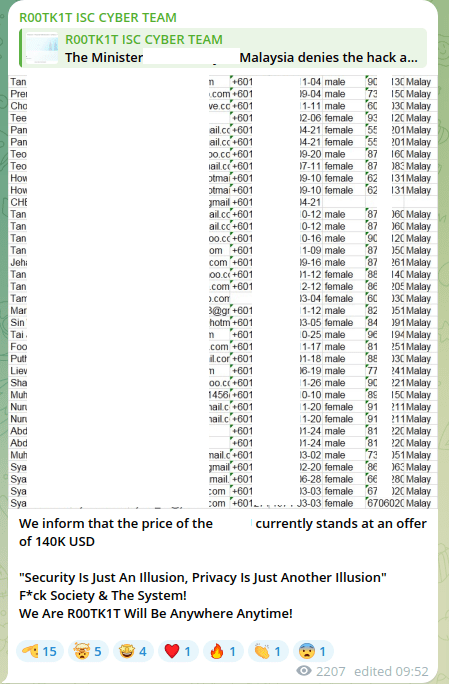

- Government data allegedly from Malaysia (offered at $140,000)

Each time, the data samples from R00TK1T were analyzed by Group-IB analysts—and each time, they were confirmed to be old leaks from unrelated sources. In one instance, data claimed to be from a Malaysian bank turned out to be from a telco. In another, the airline data was traced back to a 2019 leak from a different company entirely.

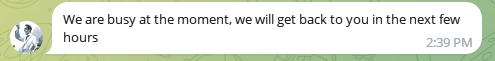

Figure 7 presents a conversation between the scammer group and Group-IB analysts. Initially, R00TK1T refused to provide any public evidence to support their claims. After persistent follow-up, Group-IB analysts were able to obtain a sample. Interestingly, before sharing the data, the scammer expressed concern about being scammed themselves—seeking reassurance that they weren’t speaking to a fraudulent buyer. Throughout the exchange, they also emphasized how busy they were and mentioned receiving multiple offers for the dataset. The data provided has been confirmed that it is old public data leaked.

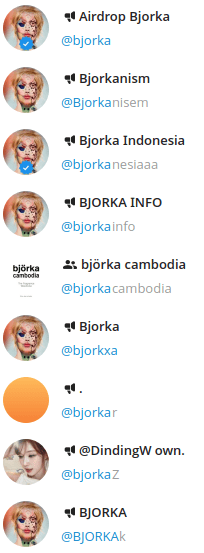

The VIP Channel Scam:

In April 2024, R00TK1T launched a private Telegram channel, charging $500 per subscriber with the promise of exclusive breach data. Group-IB monitored the channel and confirmed that every piece of data posted was from old public leaks. Still, the group reportedly attracted 20 paying members—netting $10,000 by recycling freely available information.

Figure 8: R00TK1T VIP channel scam

R00TK1T’s success proves one uncomfortable truth: Even provably fake actors can gain visibility, followers, and money—if their narrative is loud enough. And they are far from alone. R00TK1T represents just one of hundreds, if not thousands, of similar fraud actors currently operating across dark web platforms.

4. Impersonators

Level of Reliability and Credibility – 0%.

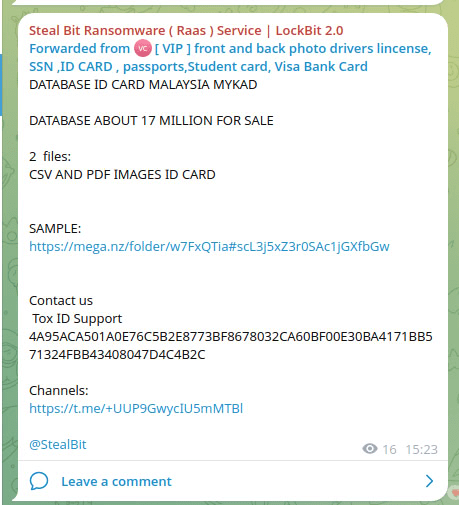

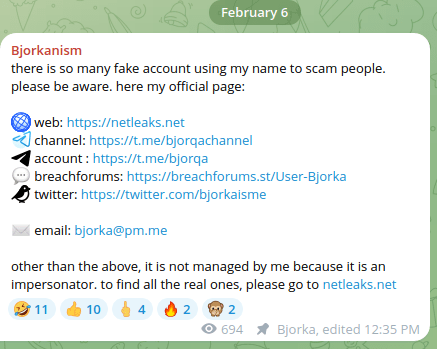

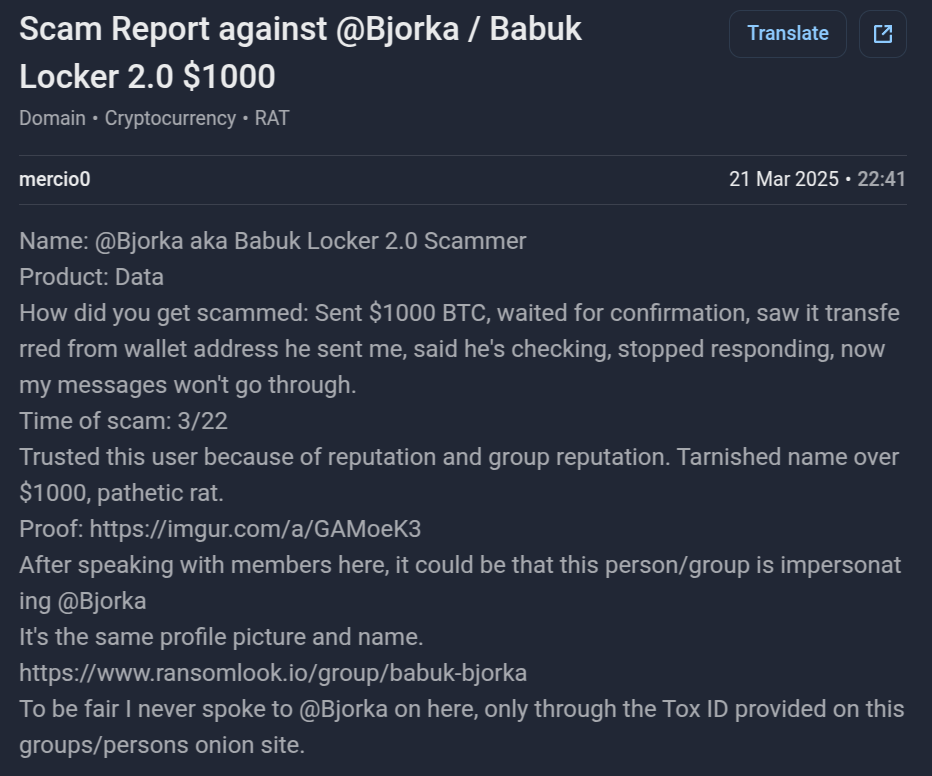

Rather than build their own persona, some scammers in the dark web impersonate established cybercriminals or ransomware groups. These include well-known names like LockBit, Bjorka, IntelBroker, LeakBase \ Chucky and many others.

These impersonators aim to exploit the reputations of real threat actors to trick buyers and draw media attention.

A common red flag is a sudden shift in communication platform or naming convention. For instance, if a ransomware group previously used dark web sites and onion domains, but is now using Telegram to sell data—something is off.

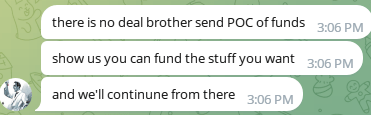

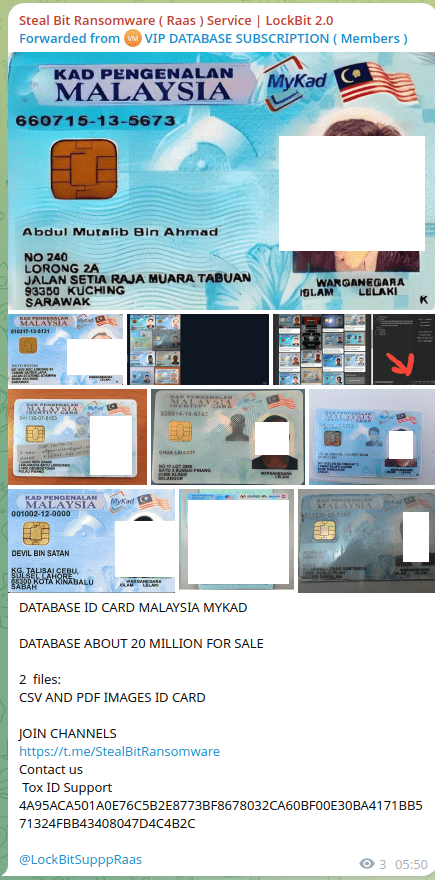

As an example, a Telegram channel named “Steal Bit | LockBit 2.0” claimed to have 17 million Malaysian MyKAD records. Upon analysis, the dataset was proven to be a mix of fake and recycled entries, with no legitimate connection to the real LockBit group.

Another example is the infamous Indonesian hacker “Bjorka” who is so frequently impersonated and had to publicly share his official contact information multiple times. These impersonator accounts often spread false leaks, post recycled data, or demand payments for nonexistent breaches. Most recently, a data buyer publicly stated that he had transferred $1,000 to a scammer posing as Bjorka. This Bjorka impersonator has also been reported as a new threat by a number of other researchers, experts, and media outlets.

There are zero confirmed cases where an impersonator turned out to be credible. These operations are always a deliberate attempt to deceive.

Figure 10: Data buyer was scammed by an impersonator posing as Bjorka

5. Scam-Prone Telegram Channels

Level of Reliability and Credibility – Close to Zero for most of them, with some exceptions.

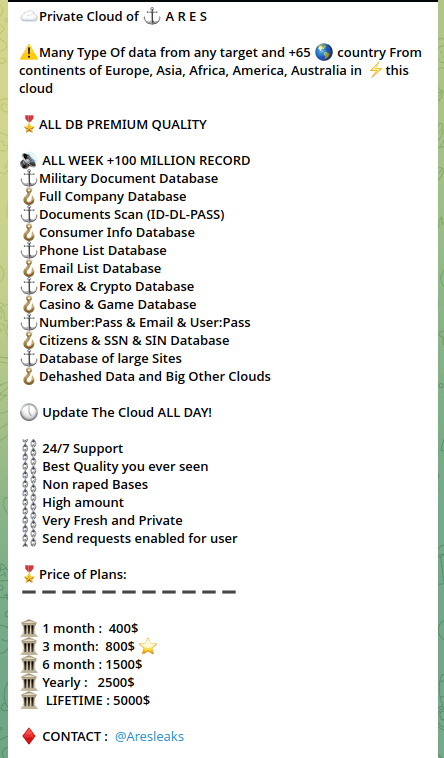

Telegram has become a hotbed for dark web activity due to its ease of use, anonymity, and minimal content moderation. While a few credible actors use Telegram as a secondary channel for communication, the vast majority of dark web-style Telegram groups are unreliable.

Most of these channels fall into one of the following categories:

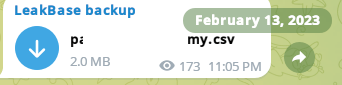

- Distributors of old, repackaged leaks

- Sellers of recycled public data

- Operators of fake VIP subscription channels

To attract followers, they often release “teaser” data dumps—real breaches posted by other actors, sometimes years earlier—and then upsell access to private groups or subscriptions with promises of exclusive, high-quality leaks.

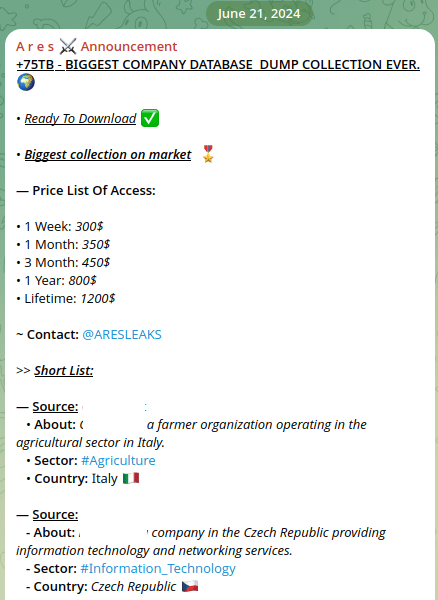

Example: ARES Group

The group ARES has been repeatedly cited by some researchers as a source of original data. However, closer analysis reveals that they regularly repost leaks originally published by ransomware groups like Play, offering nothing new.

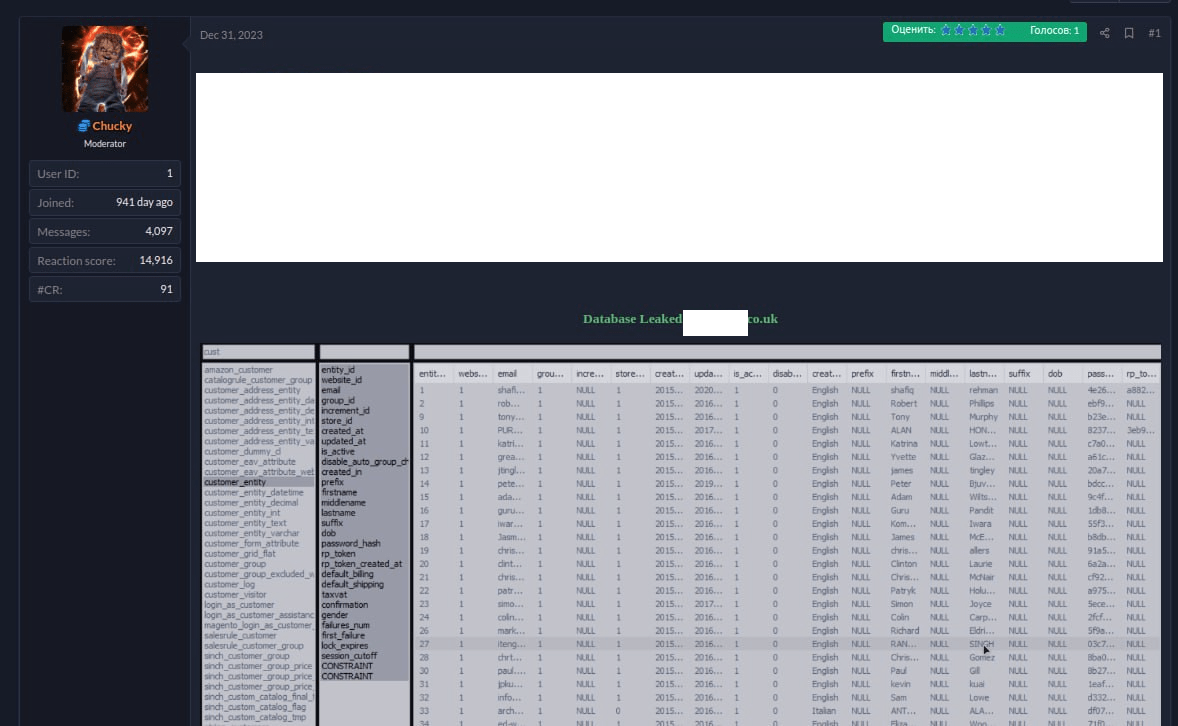

Example: DataLeakVIP Channel

In another case, DataLeakVIP, a scam channel, was caught selling a dataset from a British online retailer that had already been leaked for free by a different actor (Chucky) on a public forum just days earlier.

These scam-prone channels often operate under a false veil of credibility by mimicking the format of legitimate threat actors—posting teaser screenshots, creating flashy logos, and even fabricating “VIP” data lists. While a very small number of Telegram channels do offer legitimate breached data, the overwhelming majority rely on deception.

It’s always necessary to cross-reference with known leak sources before treating a Telegram-sourced breach as legitimate.

6. Dark Web Forum Scammers

Reliability and Credibility Level – Evaluated on a Case-by-Case basis

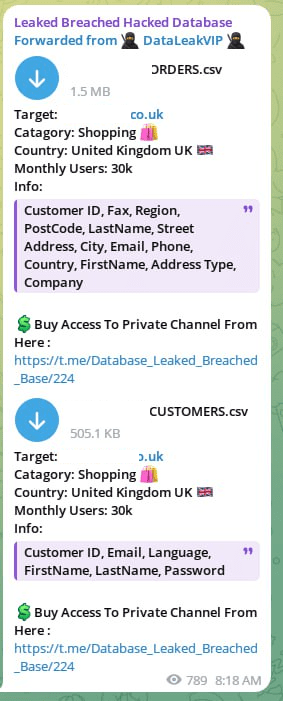

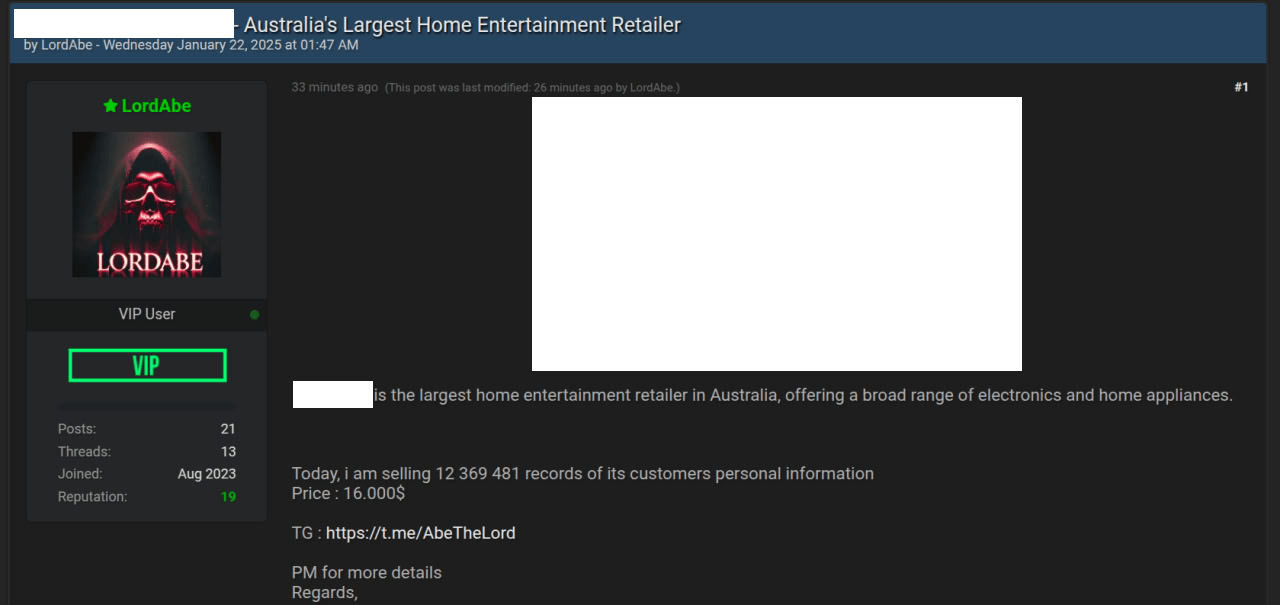

Dark Web forums remain one of the most popular platforms for cybercriminals to trade and distribute stolen data and unauthorized access. Dark web forums like BreachForums, XSS, and Exploit remain popular venues for both legitimate and fraudulent actors. Many scammers create long-term accounts, build fake credibility, and post selectively convincing content to appear trustworthy.

Even users with a decent post history and “reputation” aren’t always reliable, for examples :

- LordAbe (BreachForums): Attempted to sell data allegedly from an Australian electronics retailer. Upon investigation, it turned out to be an old leak from a bookstore

- resetmyname (Exploit): Known for claiming to sell bank data from around the world. His “sales” were actually reposts of publicly leaked data from card shops like BidenCash

Longevity or activity on a reputable forum doesn’t guarantee legitimacy. The true test lies in verifying the quality and origin of the data—and not being swayed by seller claims or forum reputation alone.

Sometimes, even reputation and time or history of activity are not reliable indicators of a cybercriminal’s integrity. As seen with resetmyname and LordAbe, both have been registered on forums for a long time, but their fraudulent activities prove that longevity doesn’t guarantee legitimacy. In these cases, the quality of the samples and evidence provided is usually a much stronger indicator of credibility than the reputation of the attacker themselves.

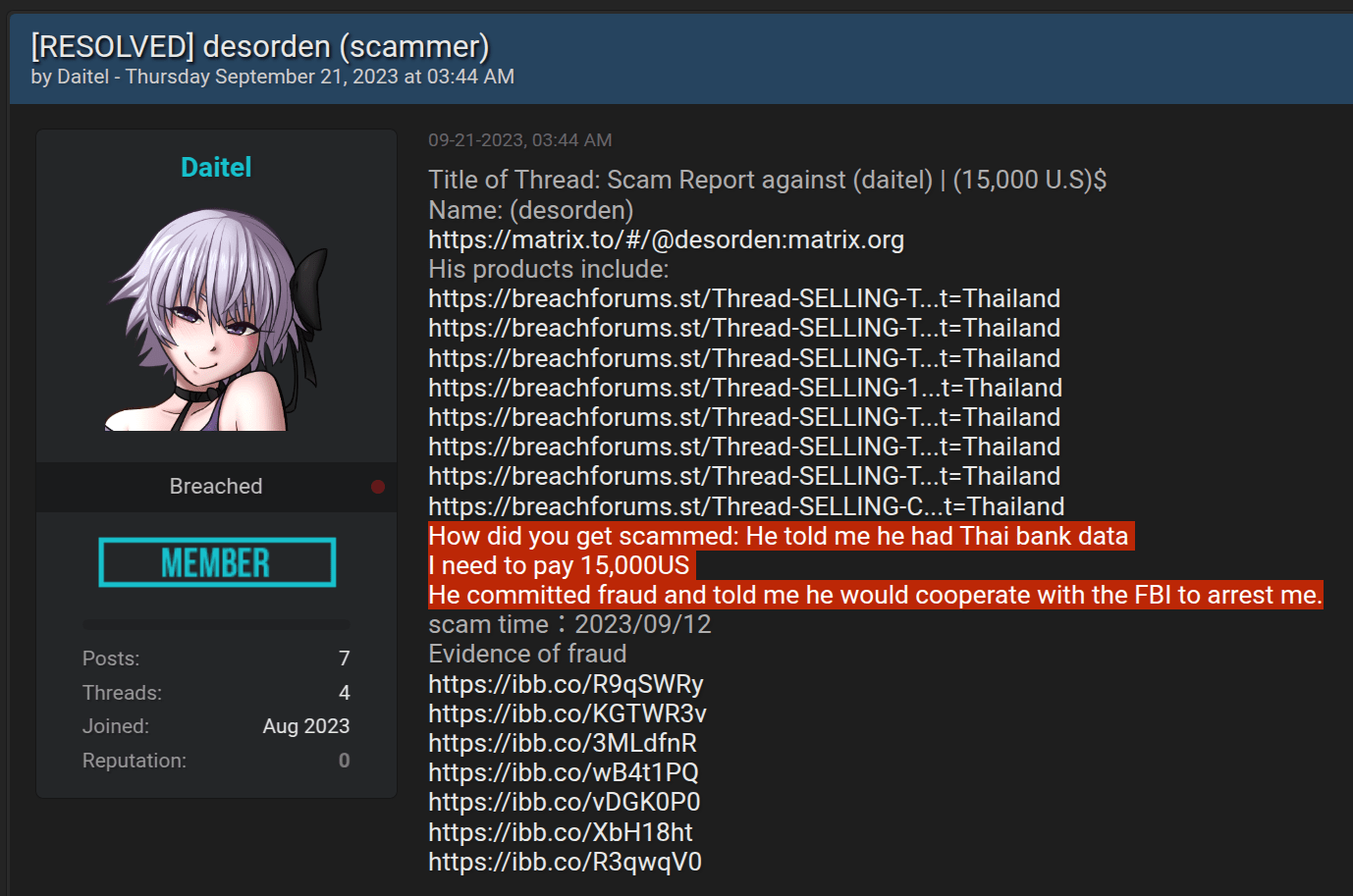

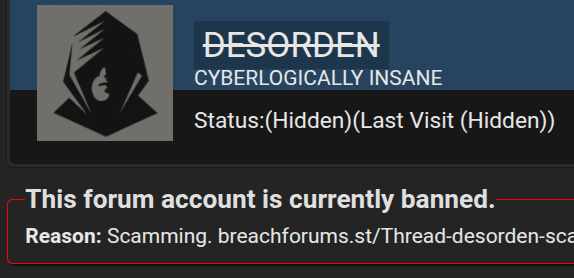

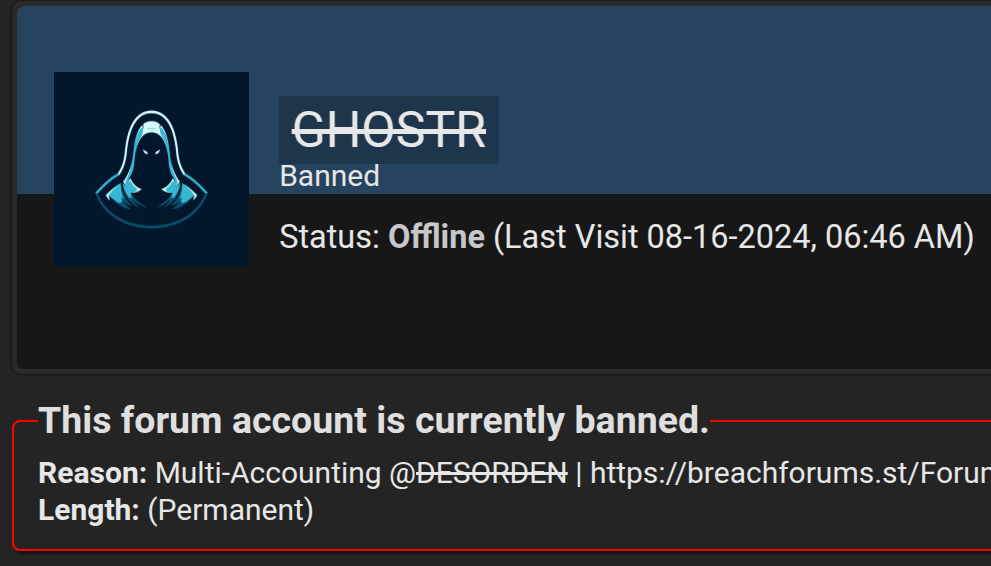

It’s important to understand that even attackers with a solid track record and a history of successful breaches can attempt to deceive. Therefore, statements from even well-known threat actors should not be taken at face value. A notable example is the case of Desorden (also known as ALTDOS, GHOSTR, and 0mid16b), who once staged a fake data sale while preparing to exit the scene. Ironically, he later returned under new aliases and was eventually arrested with the active support of Group-IB.

As part of its mission to combat cybercrime, Group-IB produces detailed reports not only on real cyberattacks but also on fake high-profile cases. These false claims can cause reputational harm to the companies whose data the fraudster falsely claims to have leaked. You can read more about Desorden’s arrest in Group-IB Press Release.

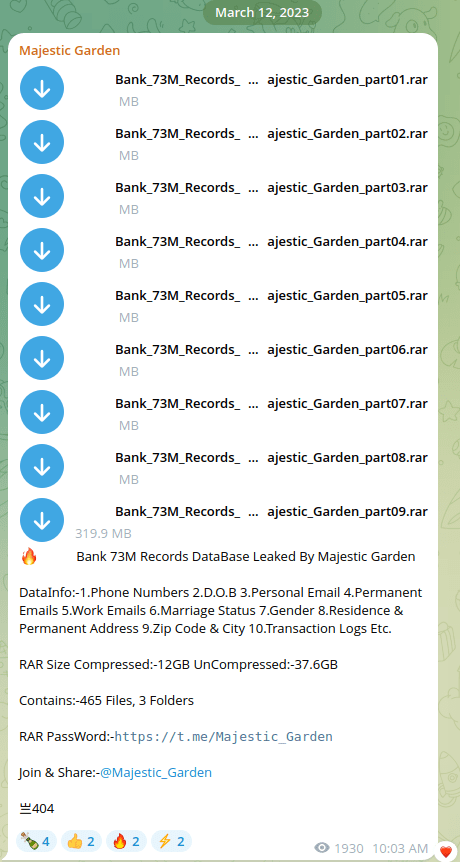

7. Distributors & ReCollectors

Reliability and Credibility Level – Evaluated on a Case-by-Case basis

While many scammers try to pass themselves off as original threat actors, some take a more subtle route: they repackage and redistribute old leaks. These actors are known as distributors or recollectors. They rarely hack anything themselves—instead, they republish public or outdated data, sometimes giving it a new name or bundling it into massive “collections.”

Not all of these actors are deliberately malicious. Some openly identify themselves as redistributors, while others falsely claim credit for attacks to boost their reputation or attract media attention. In some cases, the “original source” is misattributed altogether—credit is given to the entity that merely reported or reposted the data, rather than the actual threat actor.

Types of Distributors & ReCollectors

1. False Credit Takers

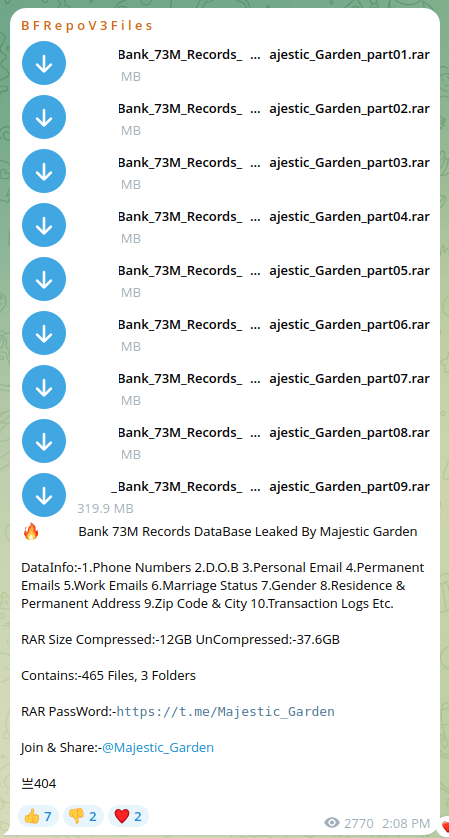

These users repost old leaks and pretend they were behind the breach. As an example, the Telegram channel Majestic Garden simply appends “by_Majestic_Garden” to files. Despite no connection to the attack, this label has been enough to fool some researchers and news outlets into reporting it as a new breach.

Figure 15: Majestic Garden Telegram Channel claiming ownership on already leaked data

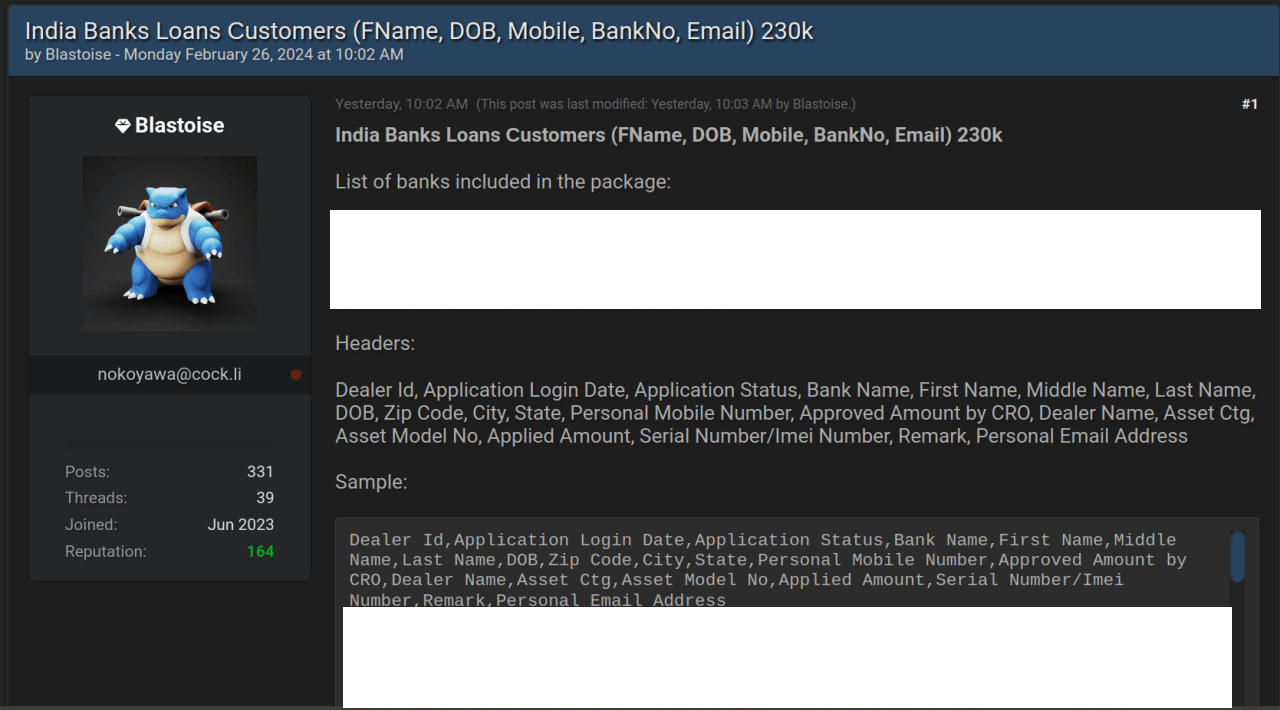

2. Reassemblers

They extract fragments from old leaks or mix multiple datasets into one “new” collection with a catchy name. A user named Blastoise took a small portion of a 2023 Indian bank leak, added references to other banks, and repackaged it as “India Banks Loans Customers”—sparking unnecessary media alarm.

Figure 16: Blastoise fake data leak announcement

Very often, such distributors and data re-collectors create a significant media buzz when researchers discover massive dumps—sometimes containing millions or even billions of user records—on various platforms. This happens because researchers or experts are sometimes unable to identify the original source of the leak, especially when the data is repackaged under a new name and published separately from the initial breach.

3. Honest Redistributors

Some actors openly state they’re only republishing data.

- BF Repo V3 Files (Telegram): Regularly republishes leaks but doesn’t claim ownership. However, they do not verify the authenticity or origin of the content—instead, they simply collect and repost any leaks they come across in bulk.

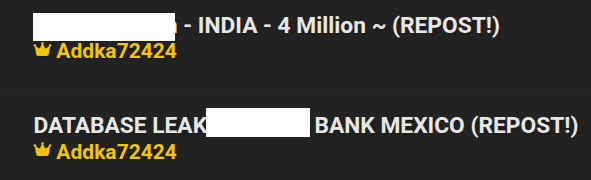

- Addka72424 (BreachForums): Known for reposting old data with expired download links. Despite disclaimers, some experts still misattribute attacks to them.

Figure 18: Addka72424 republishing of data leaks

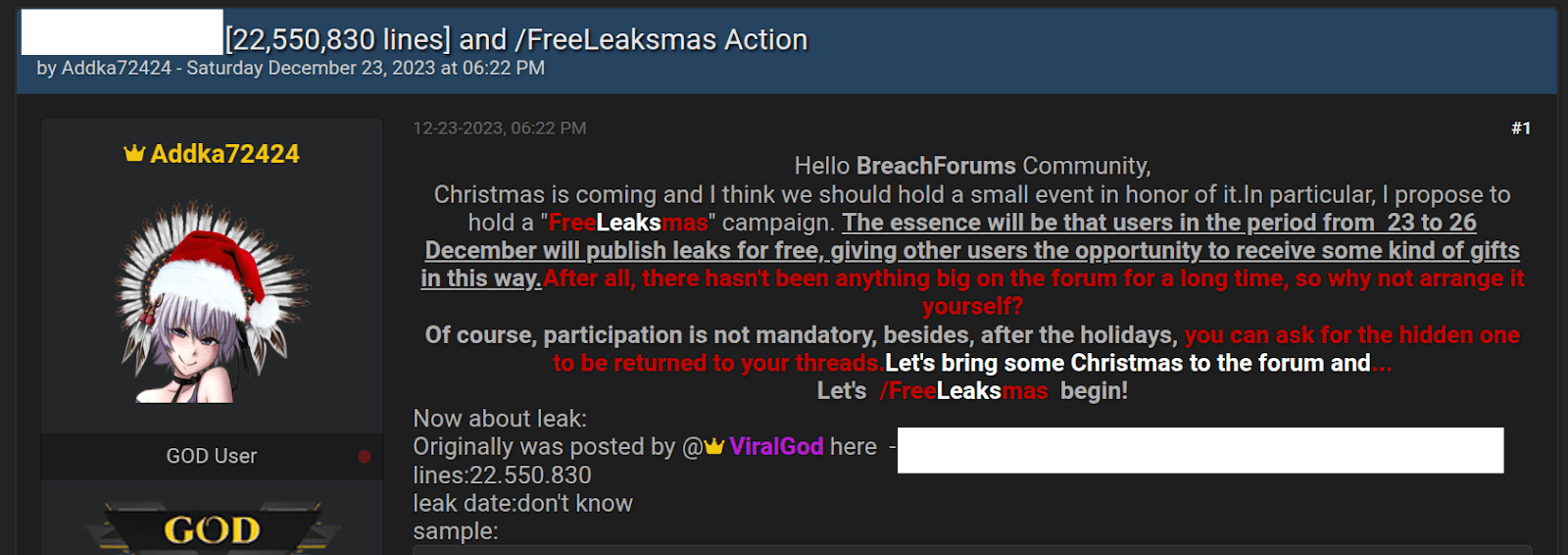

The “FreeLeaksmas” Incident

In late 2023, Addka72424 launched an initiative called FreeLeaksmas—encouraging users to repost old leaks for free as a “holiday giveaway.” While the intent may have been to revive lost links, it triggered a wave of misleading headlines, with researchers and media outlets wrongly reporting the re-released data as brand-new breaches involving “millions” of users.

When older data gets a fresh label or is shared by a new actor, it’s not always a new breach. Verification of source, timestamp, and original attacker is essential.

Figure 19: FreeLeaksmas Action announcement

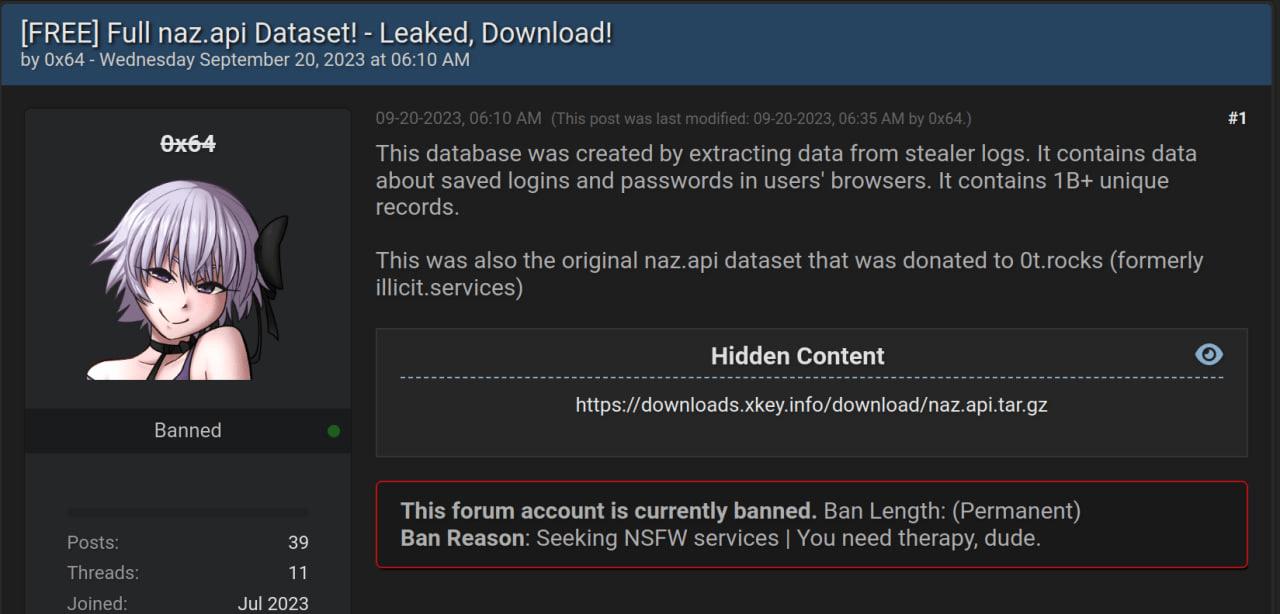

Naz.API Incident

Some distributors and recollectors go even further—creating giant “collections” by stitching together various public leaks. Of the recent cases, the most famous example of such reassembly and re-posting is the “URL-LOGIN-PASSWORD” Collection, known as Naz.API, when over 1.5 billion lines of user data were published in a single collection.

In January 2024, a researcher flagged the dataset and traced it to a user on a dark web forum—but that wasn’t the original source.

Upon deeper investigation, Group-IB analysts found:

- The original post was made on Telegram on September 12, 2023, not on the forum

- The publisher and creator of Naz.API, known as XKeyscores (aka Anime), later reposted it to the Cracked forum

- The data came entirely from public stealer logs and combolists—no fresh breach occurred

The creator even admitted this in the forum thread, stating the release was motivated by the fact that others were trying to sell this public data as their own.

Figure 20: Naz.API republication

Naz.API was not a hack—it was a curated repackaging of existing, publicly available information. Yet the story still made headlines as if it were a brand-new megabreach. ReCollectors often blur the line between awareness and deception. Some contribute to making hard-to-find data accessible again, others manipulate perception by assigning new context or taking false credit. Regardless of intent, one thing is clear: Not everything that’s “newly leaked” is newly compromised.

Common Fraud Techniques on the Dark Web

While scammer profiles vary, their methods of deception are remarkably consistent. Whether they’re hacktivists, impersonators, or recollectors, many rely on a set of core strategies to make themselves look legitimate and attract buyers, media attention, or followers. Here’s a breakdown of the most commonly used fraud tactics:

- Recycling old public leaks or stealer logs

- Fabricating entirely fake or autogenerated data

- Mixing real with fake data.

1. Recycling Old Public Leaks or Stealer Logs

One of the simplest tactics scammers use is repurposing real data from old public leaks, stealer logs, or open internet sources. Because the data is genuine, it often escapes immediate suspicion. This makes it essential for experts to investigate the true origin of the data—though, in some cases, they may overlook or ignore it entirely.

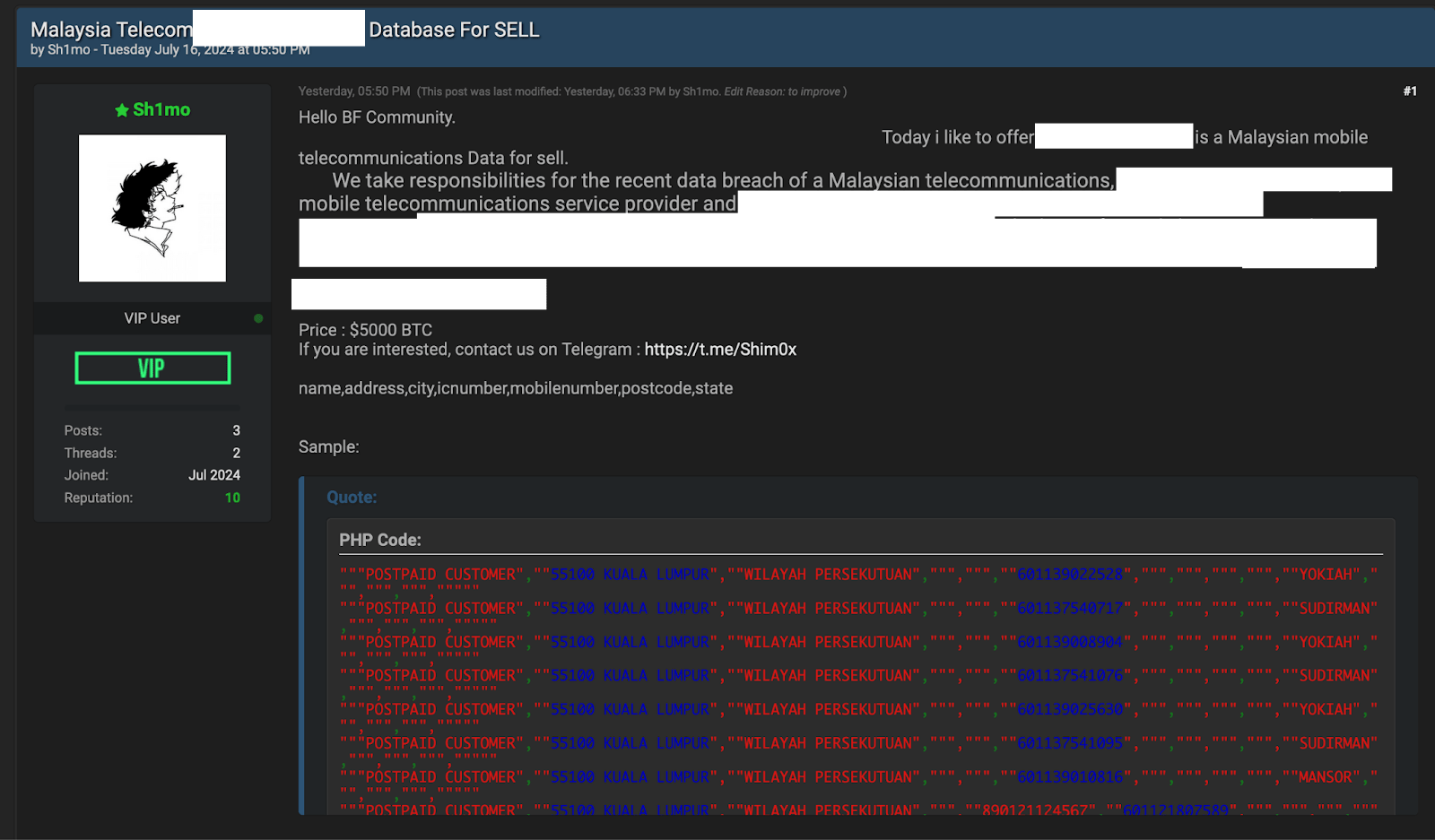

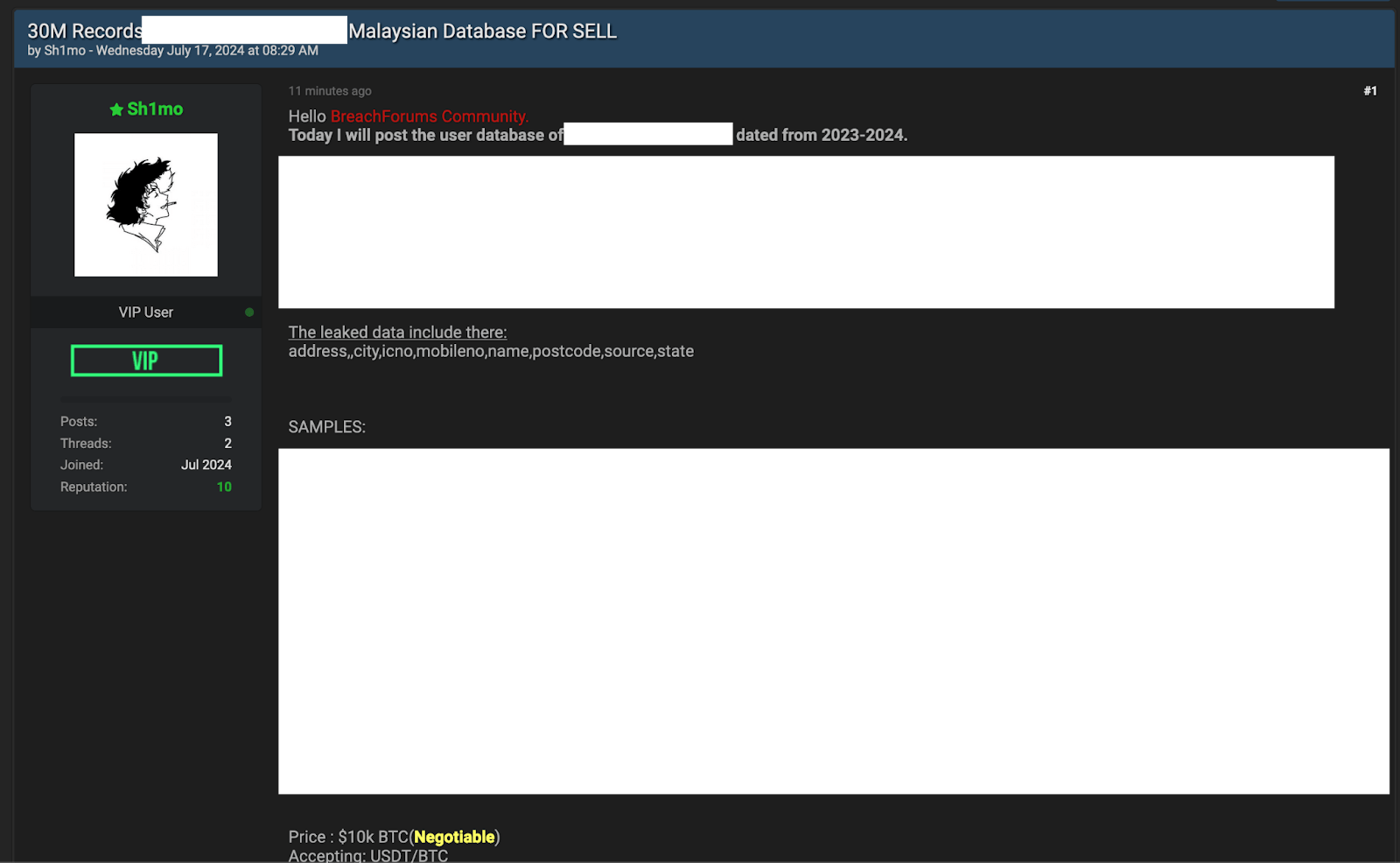

Some scammers make no effort to modify the data, presenting it exactly as it was originally leaked or stolen. More sophisticated actors may even combine records from multiple breaches to create samples that appear more credible or unique. As an example, in July 2024, a BreachForums user named Sh1mo claimed to sell two major Malaysian telco databases, priced at $5,000 and $10,000. Both were marketed as “fresh” leaks from 2023–2024. However, the provided samples matched records from a known 2018 Malaysian data bundle, already circulating on the dark web for free.

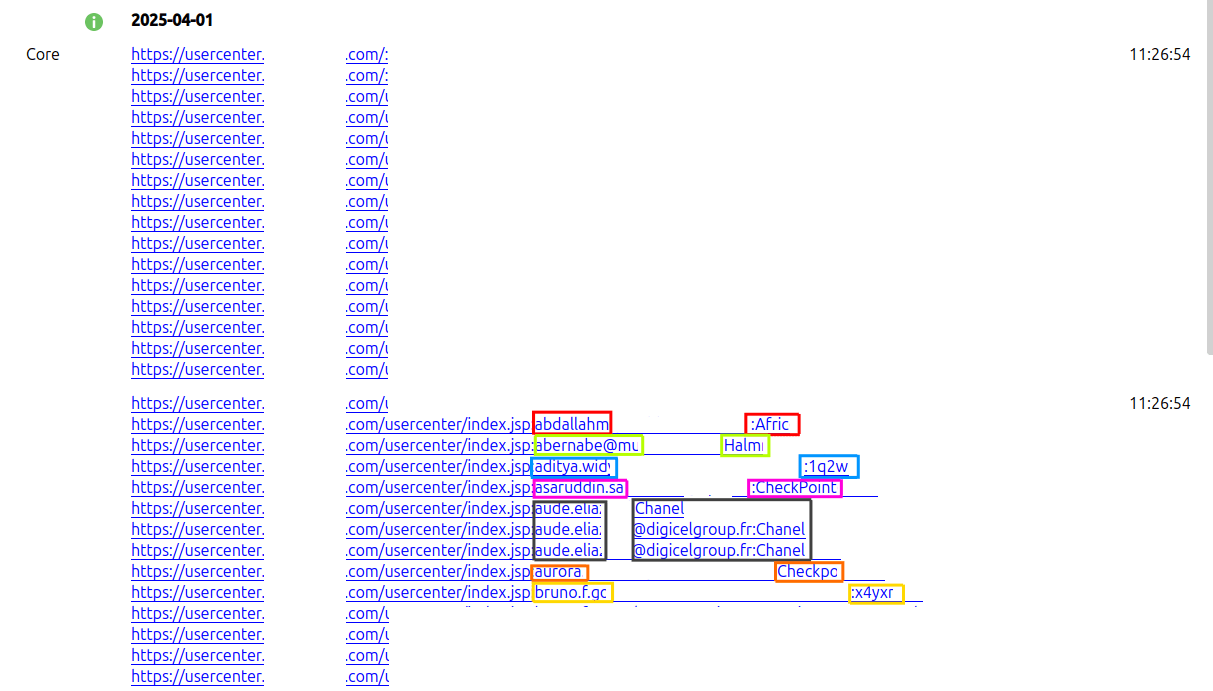

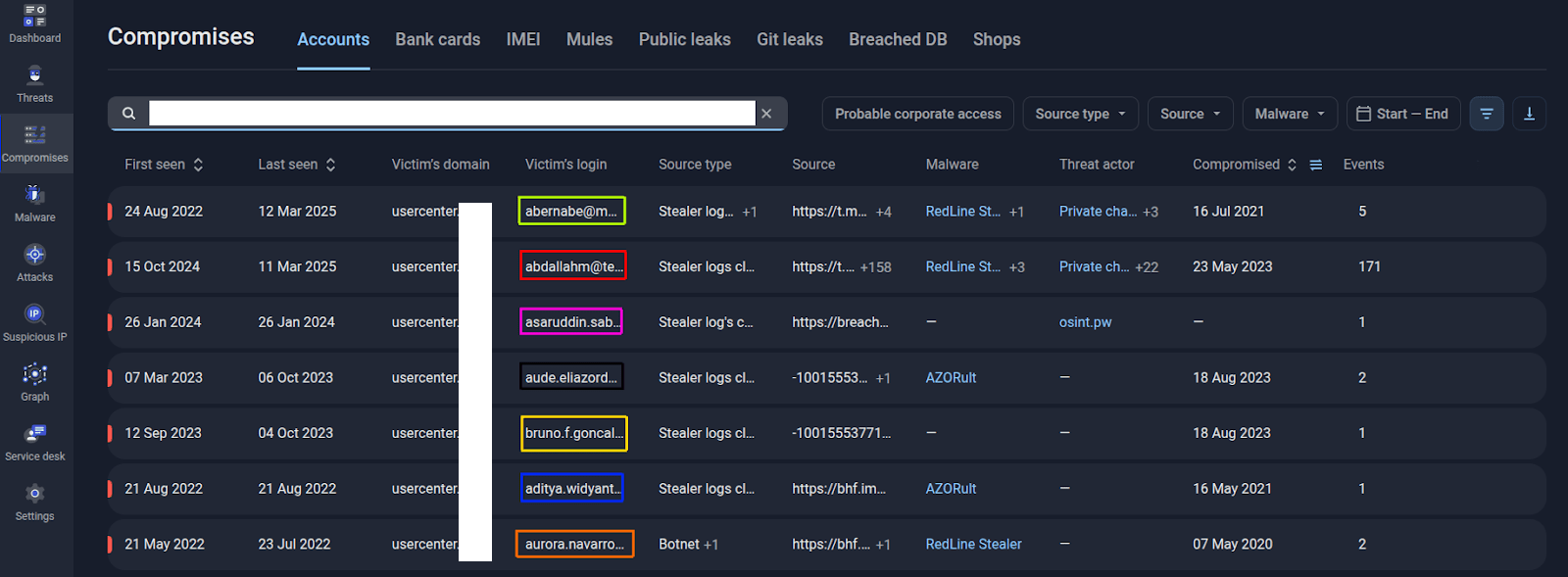

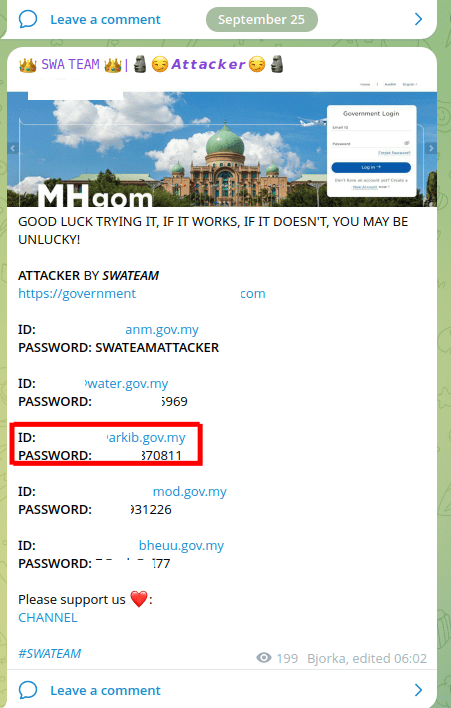

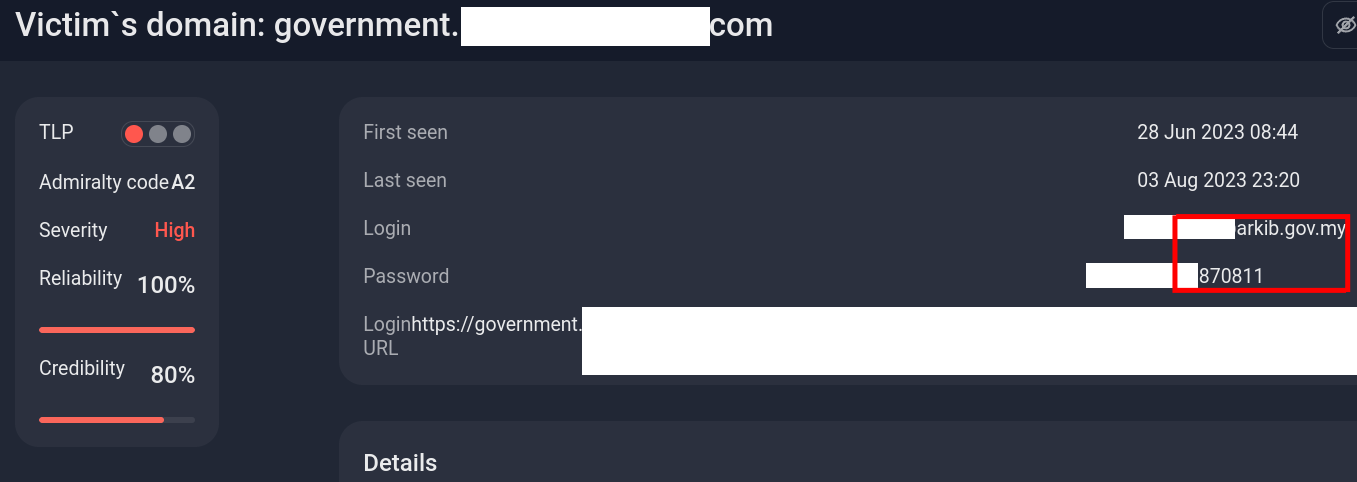

Another example of Hacktivist group “SWA TEAM”, claiming that this was “his attack,” published a number of logins and passwords for the site of Malaysian Government

Figure 23: SWA TEAM” claiming the attack

In fact, he took the data from old leaks of stealer logs, which have long been recorded in the accounts section on the Group-IB portal.

Figure 24: Group-IB portal showing the data was leaked in 2023

It’s not just data brokers who engage in deception—access sellers can be equally misleading. Some scammers attempt to trick illicit buyers by offering access to high-profile companies that, in reality, they don’t possess.

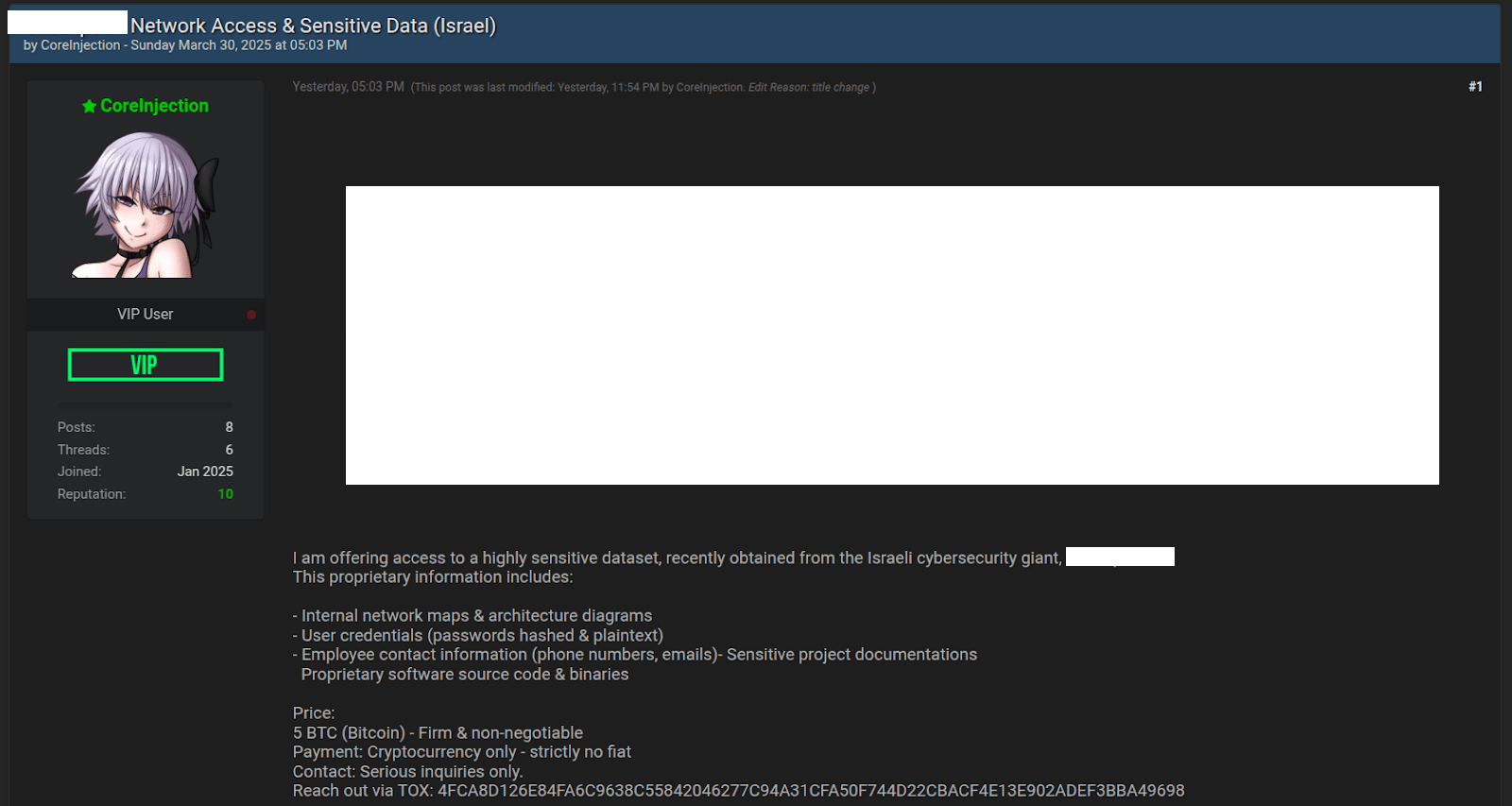

A notable case involved an actor known as CoreInjection,who advertised access and databases belonging to a large cybersecurity company. The only “proof” provided were a few vague screenshots of access proof, along with CoreInjection history of posting similar access offers- none of which included verifiable evidence.

Despite the lack of concrete proof, a number of media outlets and experts rushed to report about a probable attack/breach. When the targeted company denied any data leak and clarified that the screenshots referred to an “outdated and resolved incident”, some researchers remained unconvinced. , They continued legitimize the authenticity of CoreInjection screenshots based on past claims of successful attacks—even though those, too, lacked supporting evidence.

In a follow-up exchange with Group-IB analysts, CoreInjection shared what he claimed was “new evidence.” However, upon investigation, the data was revealed to be nothing more than public stealer logs—misrepresented as stolen user data.

Figure 24: CoreInjection’s message about the CyberSecurity Company data and sale access

Thus, CoreInjection is a fraudster who may have been able to gain some old access in the past using logins and passwords from public leaks of stealer logs. But all further evidence provided by him does not confirm that he has current access, sensitive data, or information according to the texts of his ads. Instead, he provided old data that he had extracted from old public leaks of stealer logs.

2. Fabricating Entirely Fake or Autogenerated Data

Some data being offered for sale simply does not exist in reality and could be generated using various tools. These fabricated datasets are designed to deceive buyers into believing they are legitimate, often by mimicking real data formats or including plausible details to create a false sense of authenticity. Evidence of access to any of the victim’s servers may also be fabricated.

-

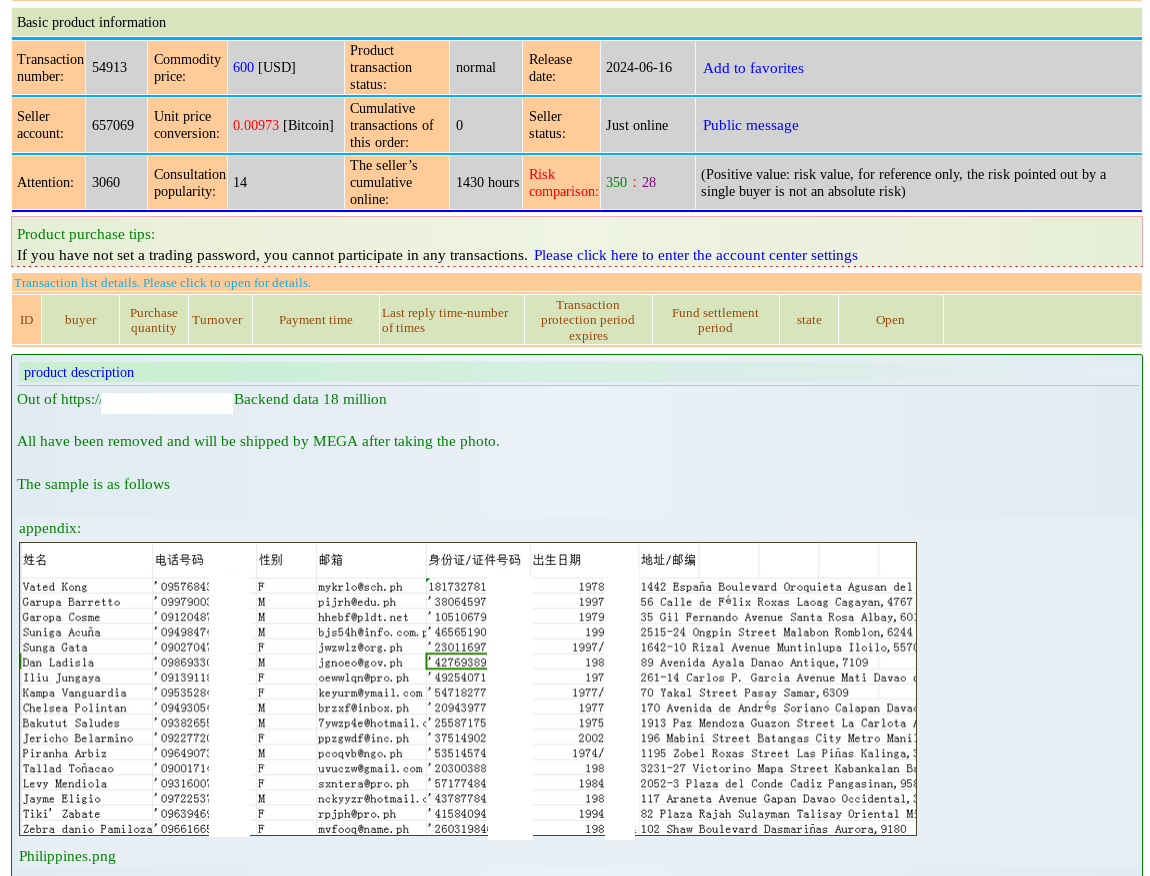

Threat actor, alias “657069”

On June 16, 2024, a threat actor using the alias “657069” listed a database for sale on the Chinese-speaking dark web onion site “Exchange” (交易市场). The database was claimed to contain 18 million records related to customers of well-known Asian marketplace.

In the sample provided, the attacker had deliberately blurred portions of the data, including phone numbers, dates of birth, and ID documents. Due to these alterations— and as confirmed by subsequent analysis— the dataset was determined to be fraudulent, making a detailed review of all sample variations unnecessary.

Figure 26: Listing of a database for sale by threat actor alias “657069”

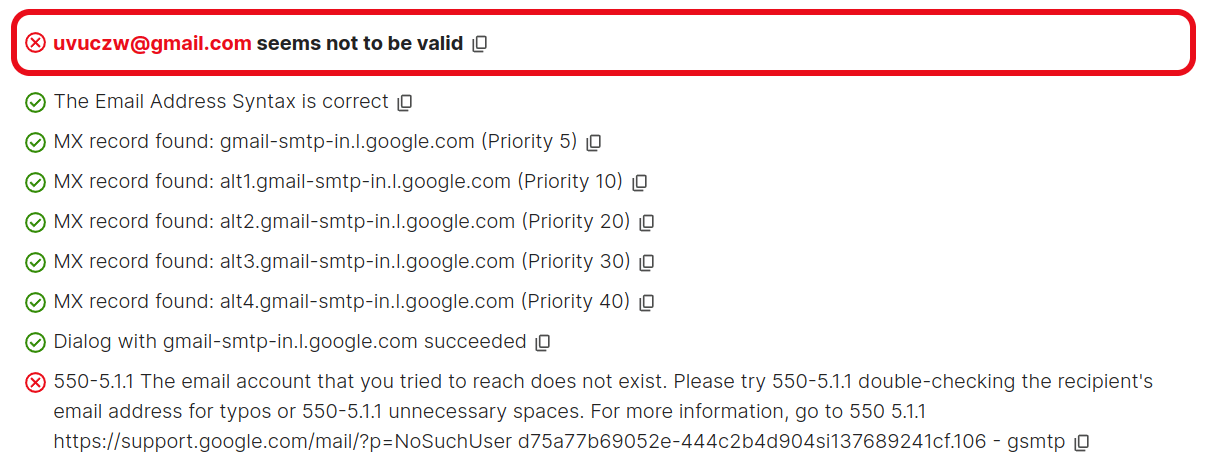

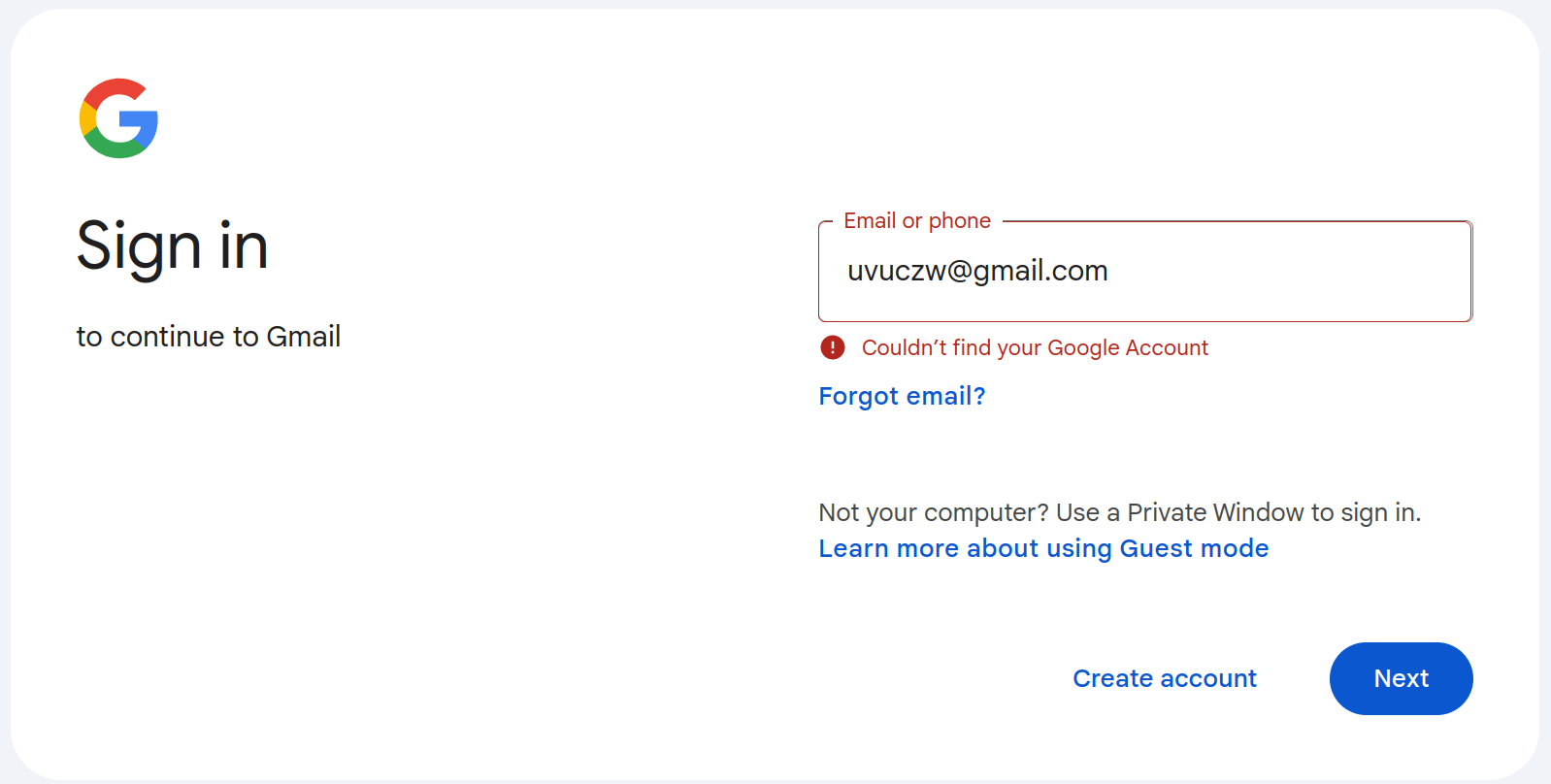

Each of the presented email and physical addresses in the sample were auto-generated and non-existent. This was evident not only from obvious signs of auto-generation —such as the random mix of letters and numbers in email usernames—but also confirmed through further verification using Group-IB internal tools and free publicly available email validation services.

All checks indicated that the email addresses were invalid. For example: uvuczw@gmail[.]com does not exist.

-

LockBit impersonation

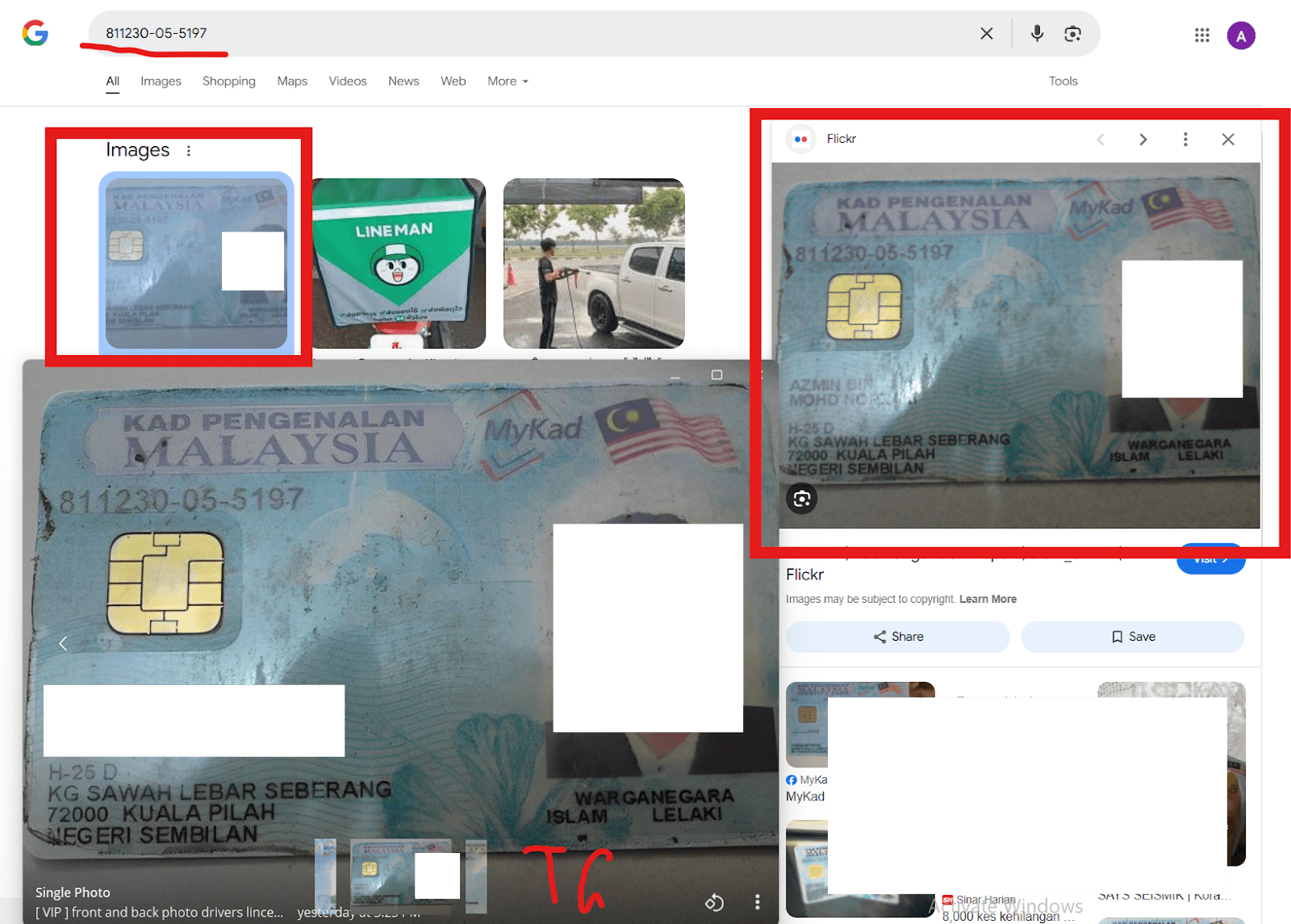

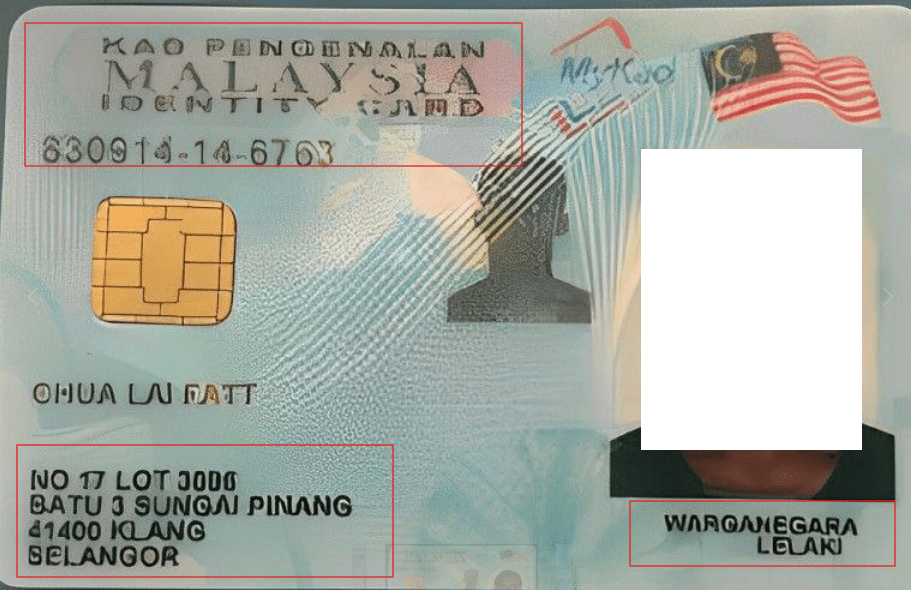

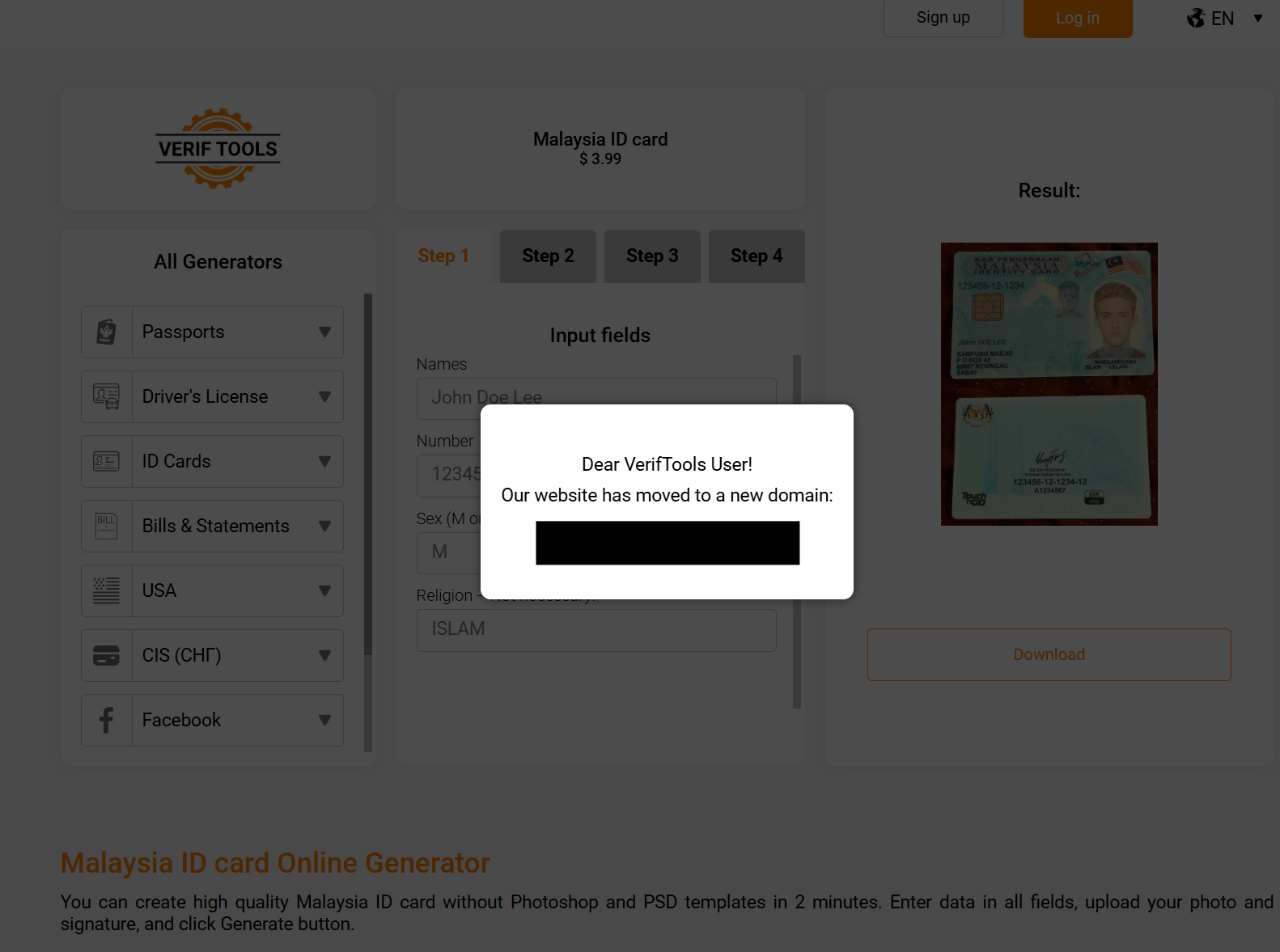

Throughout 2024, a Telegram channel impersonating the LockBit group advertised multiple datasets allegedly containing millions of Malaysian MyKAD IDs.

In every case:

- The ID images provided were either pulled from the open internet or auto-generated using publicly available fake ID tools

- Some IDs featured signs of graphic inconsistency, reused design elements, and data that failed to pass even superficial checks

- None of the datasets were tied to any verified breach

-

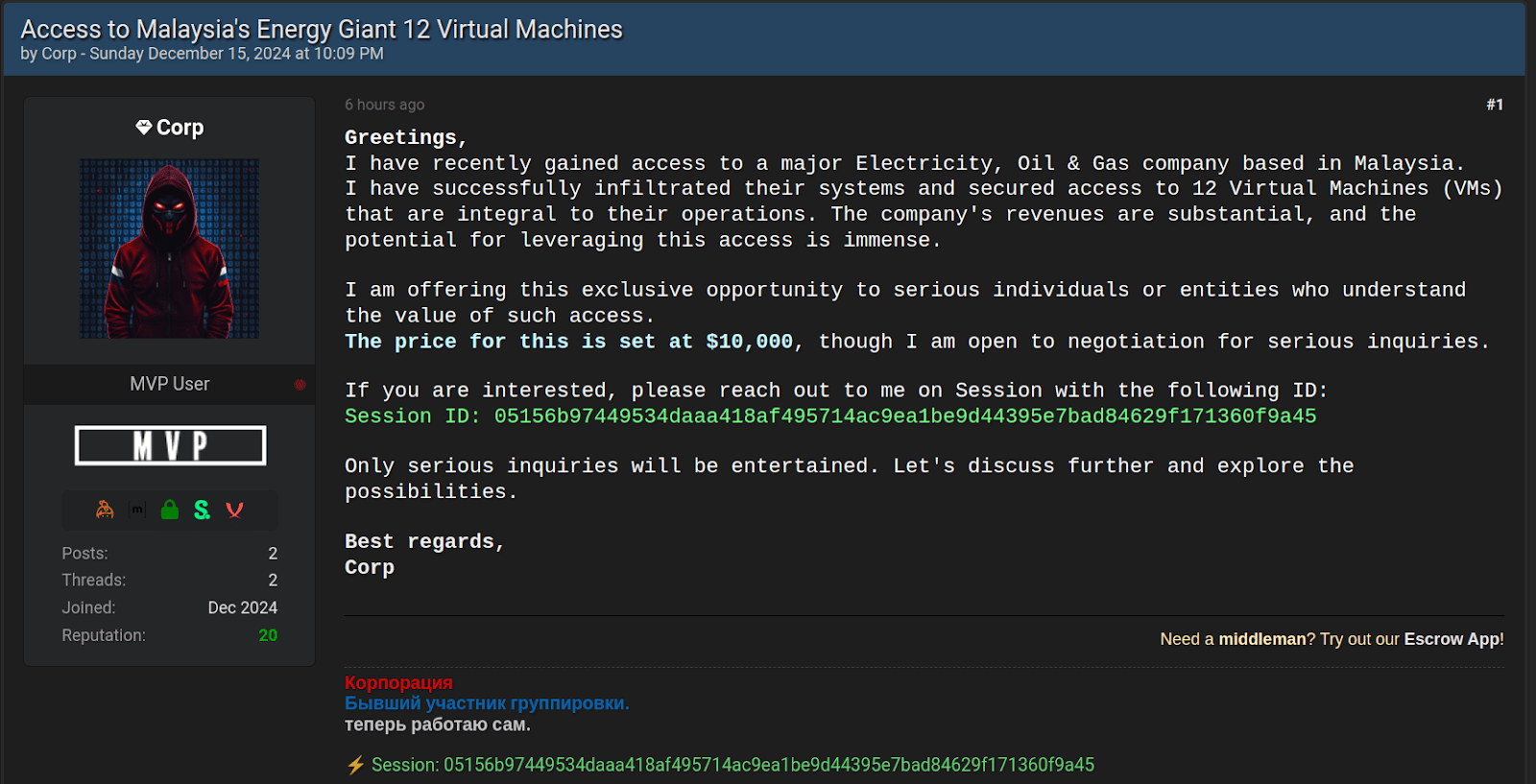

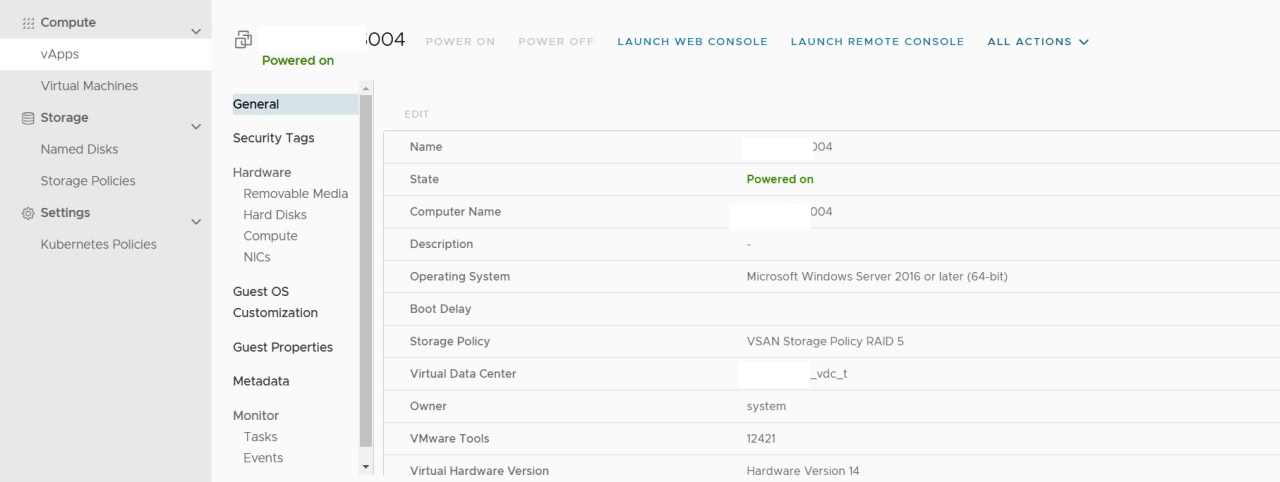

Corp

In December 2024, a user called Corp attempted to sell access to virtual machines belonging to a “Malaysian energy giant”, while screenshots were shown as “proof”, the machine names could easily have been manually set by the attacker. Moreover, the attacker refused to use escrow, had no transaction history, and offered no further evidence.

Group-IB analysts concluded the offer was most likely fabricated, and the user was later banned for deceptive behavior.

Often, when datasets contain unverifiable entries or are paired with vague or unverifiable evidence, there’s a high chance they’re autogenerated scams. The more generic the sample—and the more resistance to validation—the more likely it’s fake.

3. Mixing Real with Fake Data:

A more advanced and commonly used tactic involves mixing real user data,—often extracted from previous public database leaks (e.g., names, phone numbers, ID numbers, email addresses)— with auto-generated content. This includes fabricated details like fake account balances, passwords, bank names mentioned, and other elements designed to attract buyers while making the dataset harder to verify.

This strategy often misleads researchers and experts. Since part of the data are real and genuinely linked to individuals, it becomes difficult to label the entire set as a fake. Moreover, because the data does not match 100% with the format found in public leaks, it’s challenging to confidently trace the data to a specific breach.

To complicate matters further, scammers often combine information from multiple real leaks into a single fake sample, making it even more difficult to track the original sources or confirm the dataset’s authenticity.

-

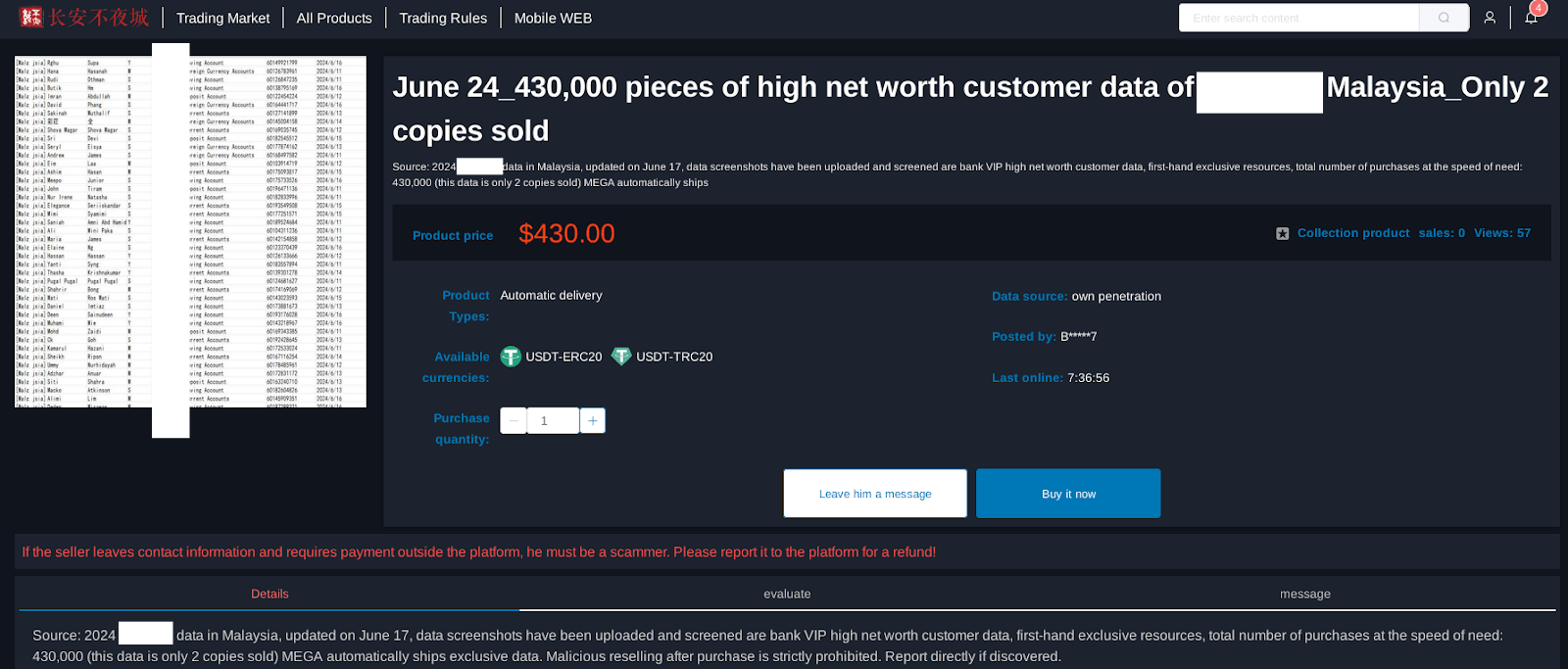

Threat actor alias B*****7

On June 17, 2024, a threat actor known as “B*****7” attempted to sell a database on the Chinese dark web forum Chang’an Sleepless Night (长安不夜城), claiming it contained 430,000 records of VIP customers from a Malaysian bank. However, Group-IB analysts concluded with high confidence that the dataset is fake, based on the following findings:

- Inconsistent Name-Phone Pairs: The names and phone numbers in the sample do not correspond to each other and show no signs of having ever been associated. In many cases, the phone numbers appear in other confirmed public leaks but are unrelated to the identities presented.

- Entire Sample Matches 2021 Social Network Leak: Every name and phone number in the sample was found in a well-known 2021 social network leak. However, the names and numbers were not paired as they were in the attacker’s sample, indicating manipulation and reassembly of publicly available data.

- Fabricated Fields: The attacker appears to have taken names and phone numbers from the social network leak and added fabricated fields (e.g., bank name, account type) to make it appear as a unique bank-related dataset.

The attacker “B*****7” repackaged existing public data with fabricated banking information in an attempt to deceive buyers. Group-IB confirmed this dataset was not authentic.

Figure 30: Listing of a database for sale by threat actor alias B*****7

-

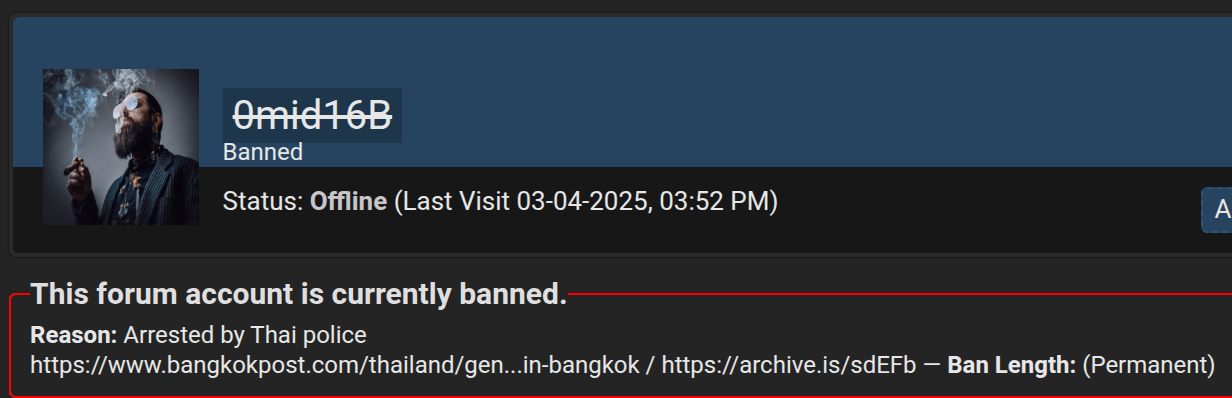

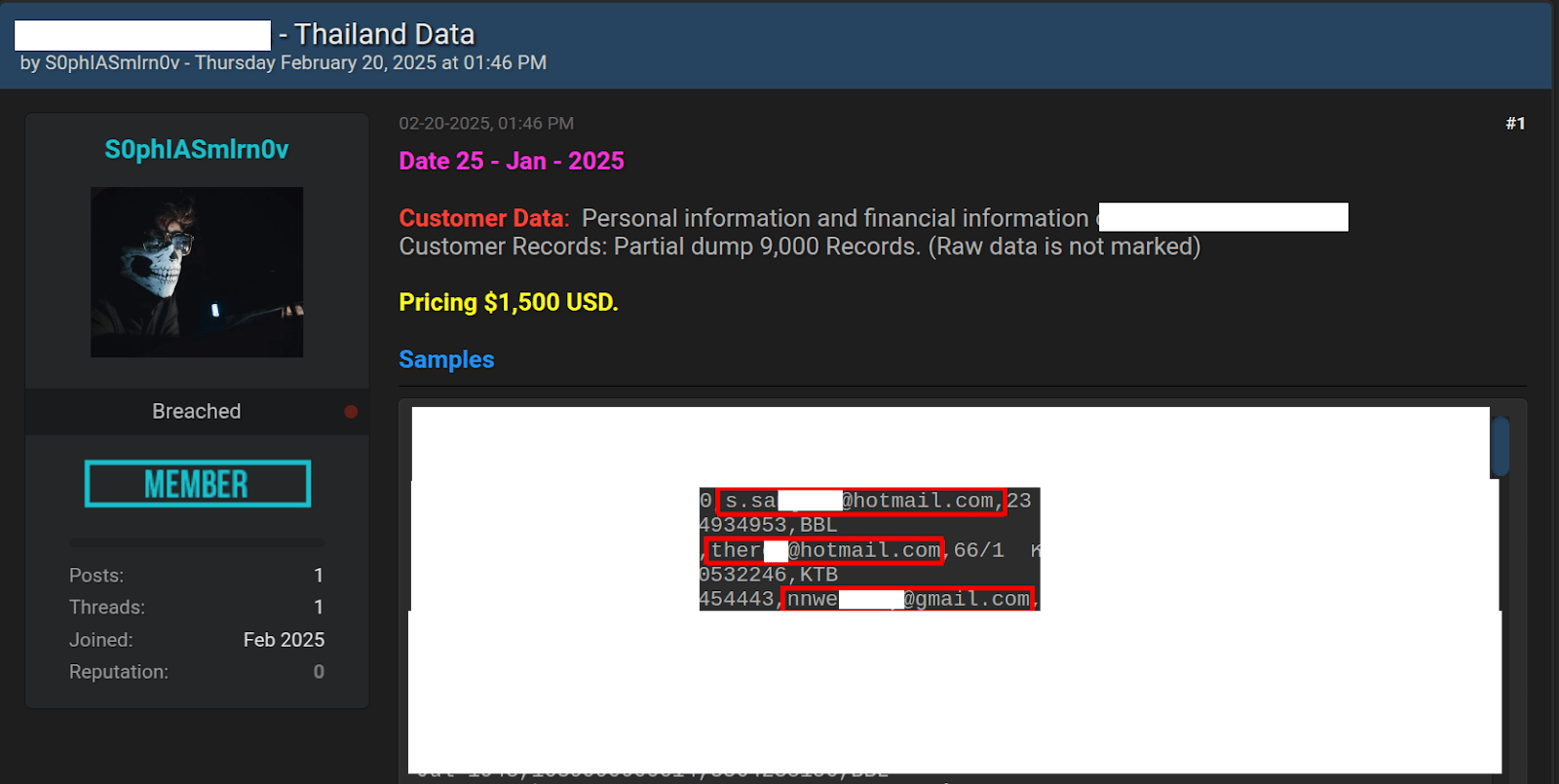

“S0phIASmlrn0v” on BreachForums

In February 2025, a newly registered user named “S0phIASmlrn0v” posted a thread on BreachForums claiming to sell data from a Thai bank. Group-IB analysis identified several strong indicators that the dataset is likely fraudulent:

- Suspicious Sample Structure:

- Only the first 15 rows include unmasked, plain-text data, while the rest of the sample is heavily masked—an unusual practice for legitimate leaks and a clear red flag.

- Recycled Email Addresses:

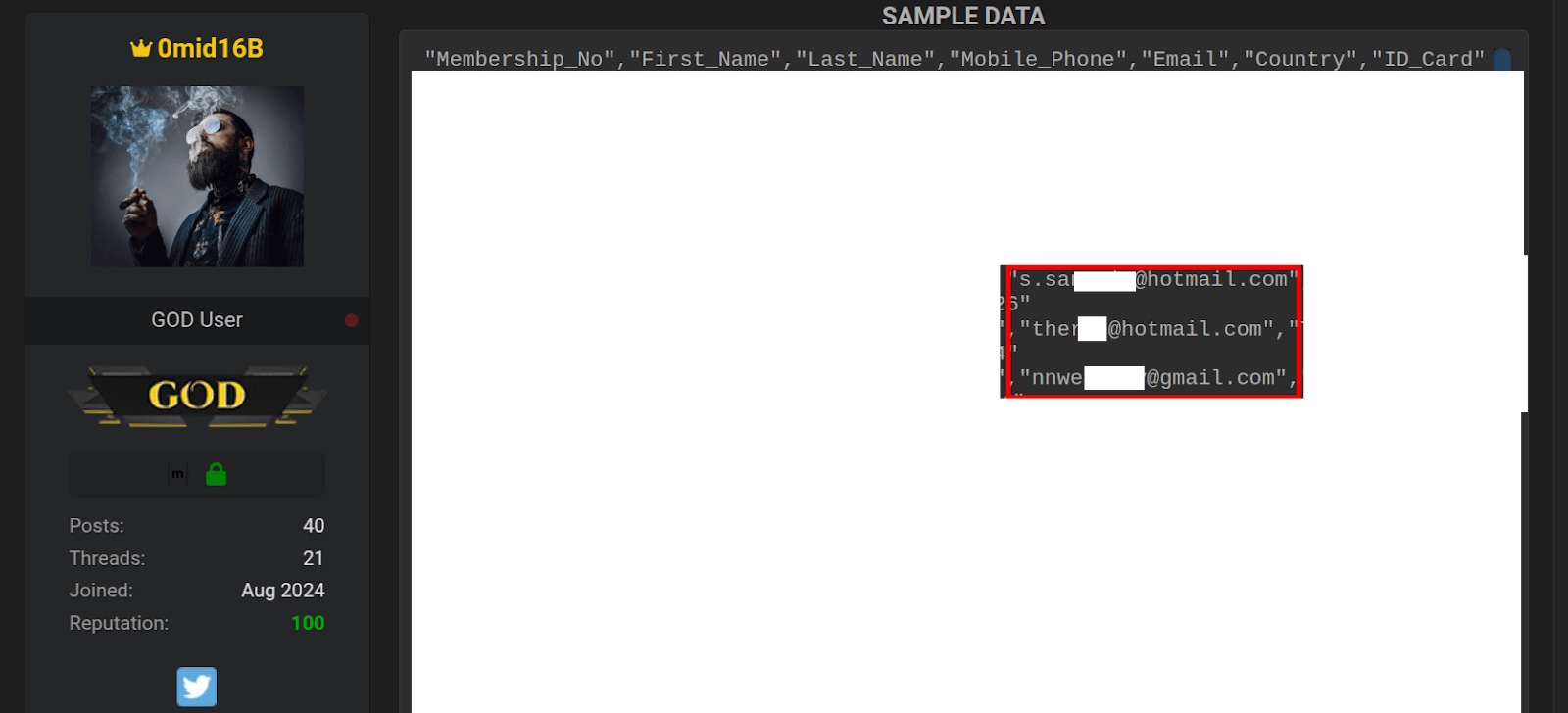

- The emails in the first 15 rows are identical to those used by threat actor “0mid16B” (aka ghostr) in a November 2024 breach of a different Thai company.

- These emails were simply copied line by line from that previous sample.

- Mismatch of Personal Details:

- Other fields (e.g., names, phone numbers, addresses) do not correspond to the actual owners of the email addresses.

- The data appears to be a mix of autogenerated and unrelated information, a known tactic used by scammers to make fake datasets look authentic.

- New User, No Track Record:

- The seller was a newly registered user, with no history of successful deals, no reputation, and no contact details provided. This lack of transparency adds to the suspicion.

- Unusually Large Sample Published:

- The post made over 3,000 out of 9,000 alleged records publicly available—over 30% of the data—which is atypical behavior for legitimate sellers.

All signs indicated that this dataset is highly likely to be fake, and the seller lacks credibility.

Group-IB assesses this as a scam attempt leveraging previously leaked data.

ธาเอก,ฉิมพาลี,+66 9***** 948,0y****v8@yahoo[.]com,3/2 ถนนฉัตรอภิเที่ยงค่ำ อำเภอภักดีชุมพล พังงา 25370,2-Apr-1950,1490*****1613,87*******37,KTB อัญธิกา,ตระกูลบุญ,09600****0325,4d****iw@gmail[.]com,4/8 ถนนนวลฉวี สุขเดือนห้า เกษตรสมบูรณ์ นครปฐม 75100,15-Oct-1972,1176*****2607,62*******41,GSB

Why does the Dark Web Fraud continue?

With so many examples of fraudulent activity uncovered – some of them repeatedly – you might wonder: Why does it keep working? Why are scammers still able to make money, attract followers, and get attention?

The shortest answer is likely because it works for everyone.

For scammers:

- They face low barriers to entry – no need to breach anything, just repackage old data or fabricate it

- They can quickly build a following with sensational posts and recycled content

- Even small success rates pay off: a scammer selling fake access or VIP subscriptions can earn thousands of dollars from just a few gullible buyers

For Researchers and Experts:

- Some cybersecurity analysts and firms rush to report “leaks” to gain visibility or drive engagement – without verifying

- Others fall for deception due to lack of context or deep dark web experience.

For the Media:

- News outlets are drawn to attention-grabbing headlines and data breach alerts, especially when high-profile names or national targets are involved

- This results in misreported stories, where recycled or fake data is covered as breaking news.

For Hacktivists:

- Attention is the currency

- Loud, unverifiable breach claims help them build reputations quickly – even if nothing they share is original or true

- Some even monetize the attention through paid channels, donation links, or fake “services”

The ecosystem feeds itself. Scammers supply fake content, analysts and media amplify it (sometimes unknowingly), and the public reacts – creating a feedback loop where fraudulence is rewarded with profit, influence, or both.

Conclusion

The key takeaway from this article is clear. Our focus should shift toward identifying real sources of threats – emerging or established – rather than endlessly spotlighting known fraudsters or rehashing scams that have been debunked countless times.

Yes, some threat actors’ claims turn out to be legitimate. And yes, rapid incident reporting is sometimes necessary, as a thorough analysis takes time. But we must remember: threats do not come only from well-known sources – they come also from a lesser-known actor operating in the shadows, often behind disposable accounts and short-lived aliases.

In many cases, it is not immediately obvious whether an incident is real or fabricated. That’s why proper verification is required. Scammers have become increasingly skilled at portraying themselves as “credible” actors and fabricating evidence of alleged attacks. Yet, in an overwhelming number of cases, a quick review of the source, the attacker’s profile, the nature of the claim, and any provided “evidence” makes it clear that the probability of deception approaches an absolute 100%. In practice, the idea that someone who has faked 100 attacks will suddenly carry out a real one is almost nonexistent. From the start, these fraudsters operate with the sole intention of deceiving – and they often succeed. Despite being exposed repeatedly, these scams continue to attract attention from experts, researchers, cybersecurity companies, and the media. Hiding behind cautious disclaimers like “The attacker claims…” or “This information requires verification”, “raising awareness about potential threats”, may seem responsible, but in practice, it only amplifies scammers and stirs unnecessary panic. Therefore, alongside rapid reporting, priority should be given to reliable sources that provide in-depth analysis and detailed reports, rather than unverified claims or isolated statements.