Introduction

Combolists and URL-Login-Password (ULP) files have existed since the earliest user data leaks. These files offer a convenient format for storing and distributing compromised credentials — typically just a username (or email) and password — where all “unnecessary” information is removed. It’s simplicity makes them ideal tools for cybercriminals launching attacks such as credential stuffing, phishing, and other forms of account-based exploitation.

With the advent of modern infostealers, stealing login credentials has become easier and more automated than ever. At the same time, distributing stolen data has been simplified through platforms like dark web forums, file-sharing services, and Telegram channels.

As a result, the release of new combolists and ULP files now happens on an industrial scale. These files often claim to contain billions of fresh, high-quality credentials, continuously feeding the underground market with massive volumes of exploitable user data.

Cybersecurity researchers and threat intelligence firms frequently analyze these combolists and ULP files, issuing warnings about the scale and potential impact of such leaks. However, in practice, combolists and ULP files have largely become outdated and unreliable as sources of new compromise. While they remain a part of the cybercrime ecosystem, the majority of data in these collections is recycled, stale, or poorly verified. For defenders, their true value lies more in historical analysis and credential exposure tracking than in identifying fresh threats.

Key discoveries in this blog:

- Despite bold claims, most combolists and ULP files are recycled from past breaches or autogenerated — rarely offering fresh, actionable data.

- Many sellers falsely label combolists as infostealer logs to boost credibility, but real infostealer logs contain far more than just login credentials.

- Actors like AlienTXT gain attention by repackaging old data, not by leaking anything new.

- Tags like “FRESH” or “2025 PRIVATE LEAK” are often just marketing tactics — used to make stale data appear new.

- Overhyping old leaks causes alert fatigue, reducing user responsiveness when real breaches occur.

What is a combolist?

Combolist is a text file that typically contains user credentials such as email addresses, as well as login IDs and passwords in hash or plain text, often displayed in a “EMAIL:PASSWORD” format, such as EXAMPLE@EMAIL[.]COM:PASSWORD1234.

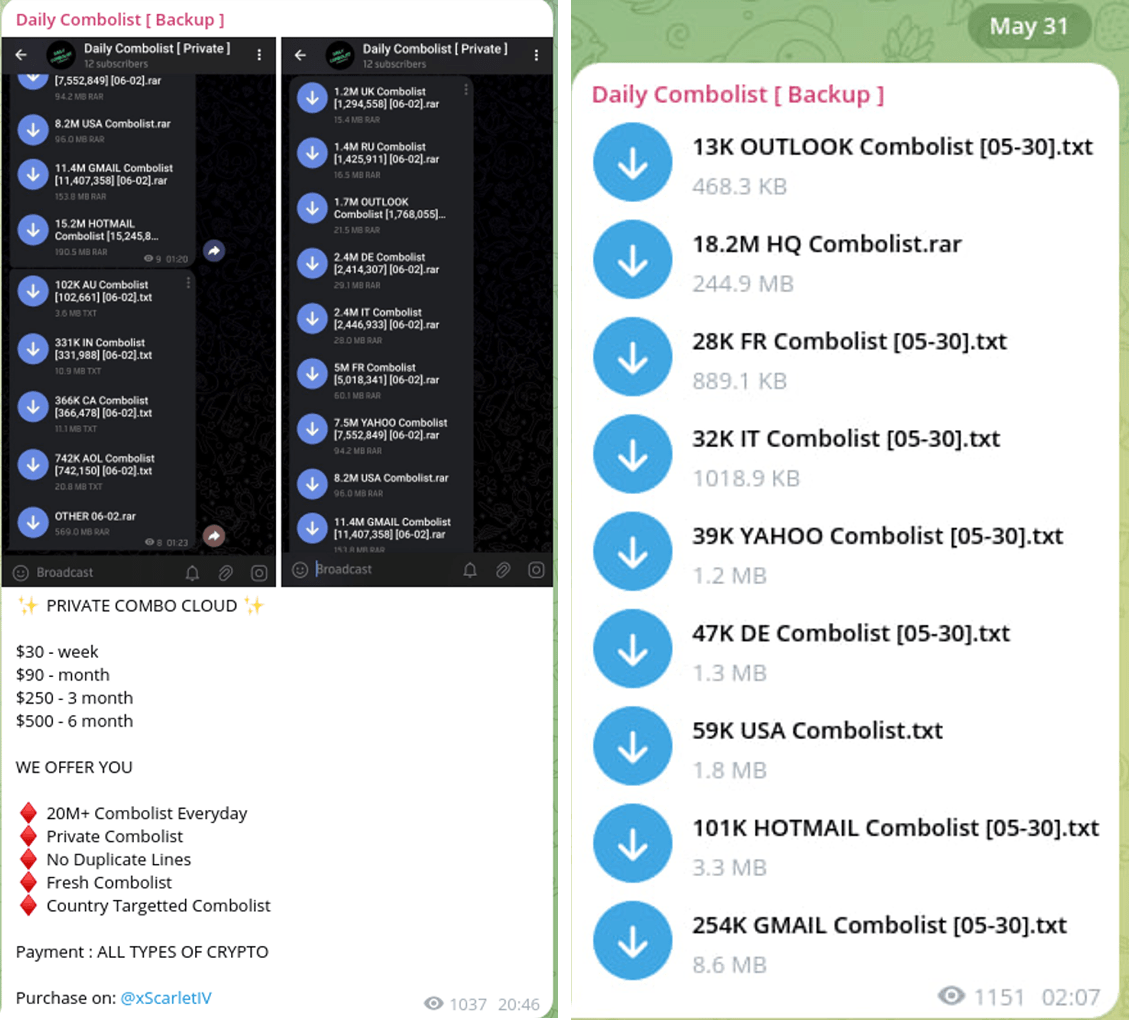

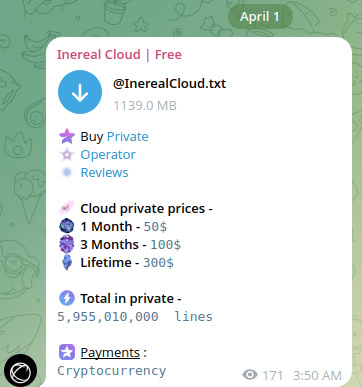

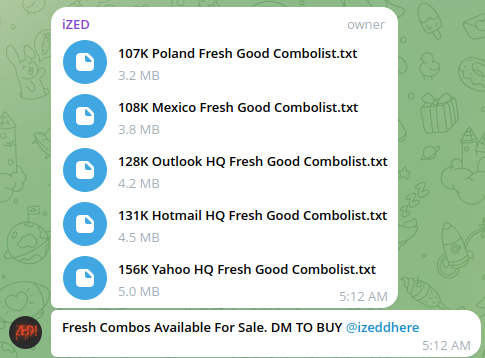

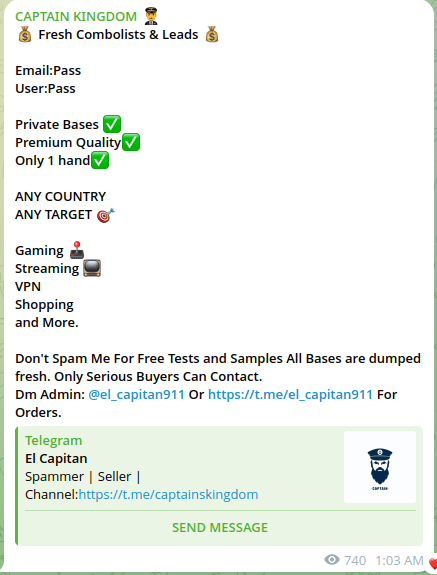

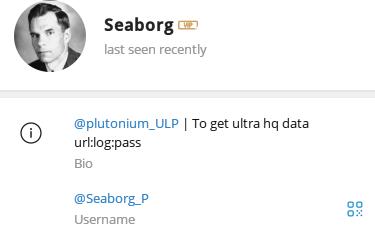

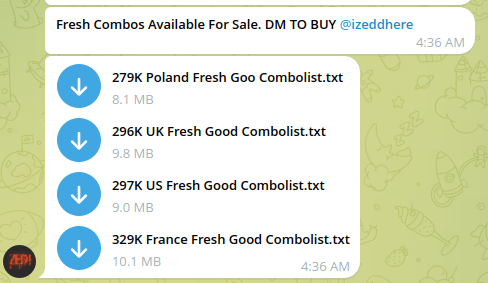

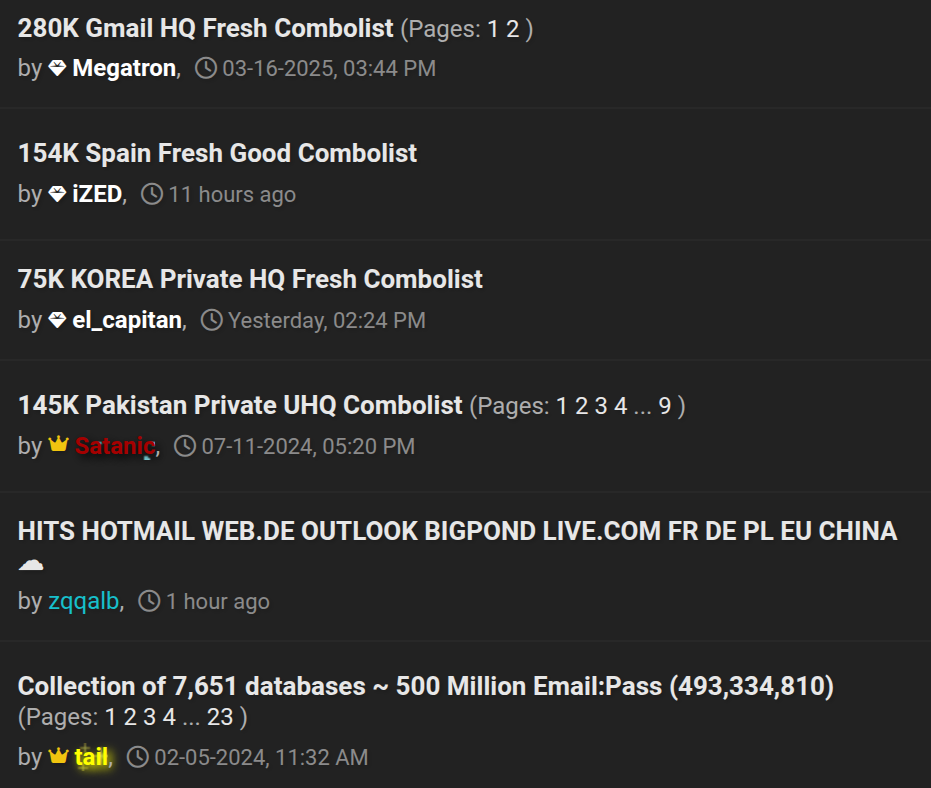

Combolists are typically advertised and distributed via dark web forums, as well as on Telegram, as shown in screenshots below:

Figure 1. A screenshot of a message advertising the sale of several combolists via a Telegram channel.

Figure 2. A screenshot of a series of posts on a dark web forum advertising the sale of combolists.

What is a ULP file?

ULP is a text file containing user credentials that is very similar to combolist, but the key difference in the ULP is that it also contains the URL for its use, such as: Websitename[.]com\login:EXAMPLE@EMAIL[.]COM:PASSWORD1234.

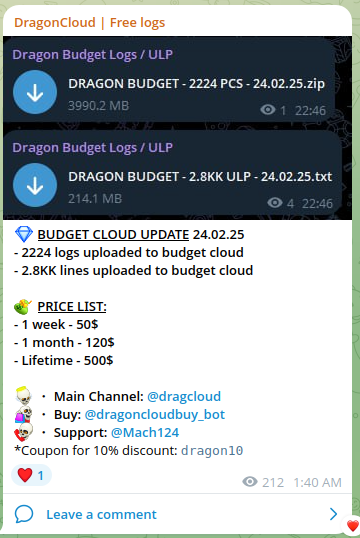

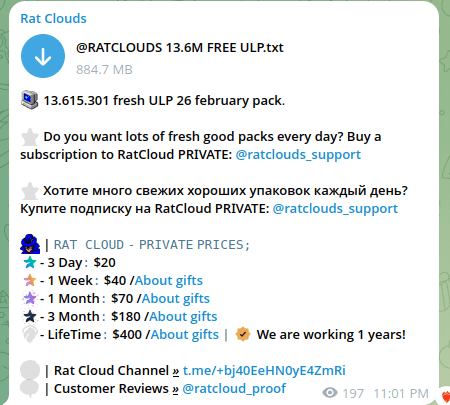

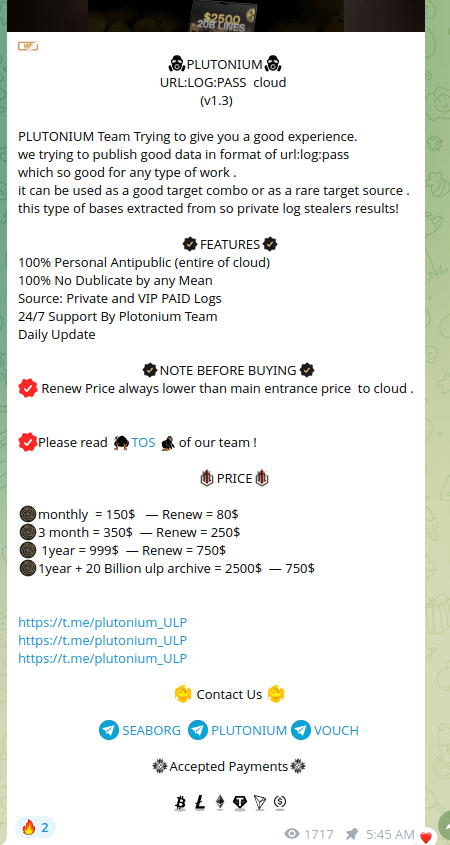

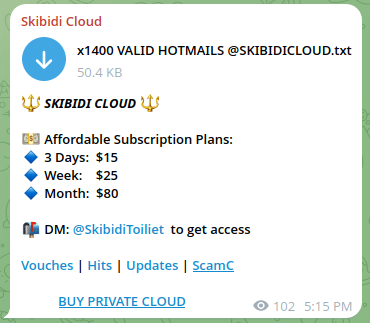

ULP files are also typically advertised and distributed through Telegram and dark web forums, as shown in the following screenshots.

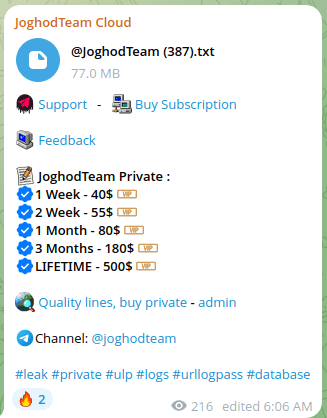

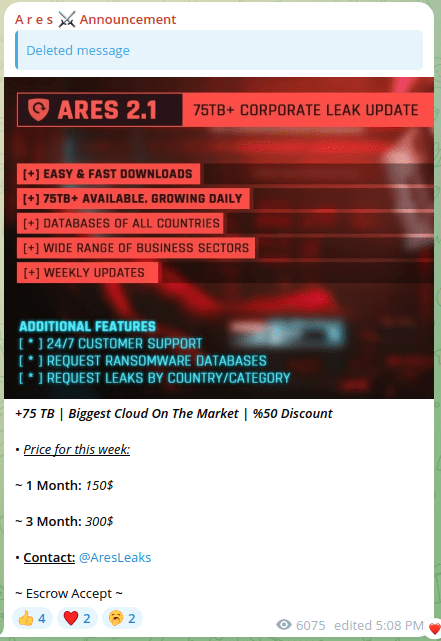

Figure 3. A screenshot of a message advertising the sale of several ULP files via a Telegram channel.

Figure 4. A screenshot of a series of posts on a dark web forum advertising the sale of ULP files.

What is an infostealer log?

An infostealer log is a dataset containing information obtained from the user’s infected device by infostealer malware. The infostealer malware can harvest sensitive information from the user’s device, including login attempts to various websites, capturing and storing website URLs, as well as login credentials such as usernames, emails and passwords. A typical infostealer log would look like this:

URL: hxxps://www[.]SITE[.]com/newlogin

Username: nickname_123

Password: ABCD_1234

Application: Google_[Chrome]_Default

===============

URL: hxxps://login[.]SITE2[.]com/common/oauth2/v2.0/authorize

Username: EMAIL@gmail[.]com

Password: EFGH_4321

Application: Google_[Chrome]_Default

A full infostealer log file tree for one infected device may look like this. The Passwords.txt file contains info about users’ credentials and URL:

├── Autofills

│ ├── Google_[Chrome]_Default.txt

│ └── Microsoft_[Edge]_Default.txt

├── Cookies

│ ├── Google_[Chrome]_Default Network.txt

│ ├── Microsoft_[Edge]_Default Network.txt

│ └── Opera GX_Network.txt

├── DomainDetects.txt

├── ImportantAutofills.txt

├── InstalledBrowsers.txt

├── InstalledSoftware.txt

├── Passwords.txt

├── ProcessList.txt

├── Steam

└── UserInformation.txt

Differences between combolists, ULP, and infostealer logs

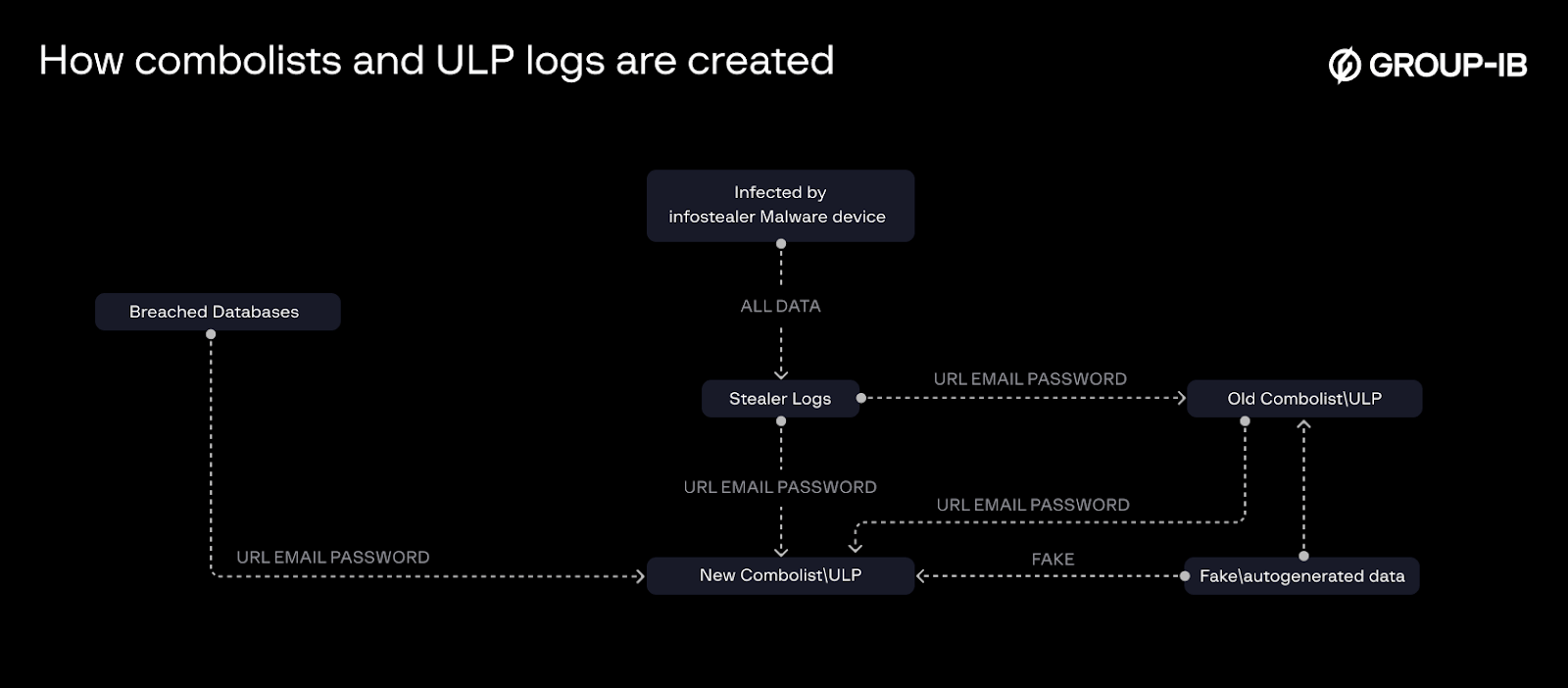

Infostealer logs are generated when infostealer malware extract data from infected devices, whereas combolists and ULP data are compiled from various sources, including infostealer logs, database leaks, previously circulated combolists, and even fake or autogenerated data.

Schematically, the simplest general path for creating each of the three types of data, and what it consists of, can be represented as follows:

Figure 5. A general schematic of how combolists and ULP may be generated.

Why Combolists and ULP Files Shouldn’t Be Confused with Infostealer Logs

On the dark web, as well as articles by cybersecurity researchers and experts, there is frequent confusion when the contents of ULP and combolist are referred to as infostealer logs, or when it is reported that the data obtained from these sources. This is not always the case.

Confusion between ULP files, combo lists, and infostealer logs on the dark web arises from a misunderstanding of their origin and content. In the following section, we clarify why data from combo lists is frequently misidentified as infostealer logs.

ULP file ≠ Infostealer log

Why it’s confusing:

- ULP is a format in which some infostealers actually use to save user credentials.

However:

- Not every ULP file is created from a infostealer log.

- A ULP may simply be a converted dump from another source, rather than a “clean” infostealer log.

Reality:

If an “infostealer log” is offered for sale in the form of a ULP file, this does not guarantee that the data is fresh, or that it was stolen directly from an infected device.

Combolist ≠ Infostealer log

Why it’s confusing:

- Combolists (email:password lists) are often compiled from a variety of sources,including leaked databases, autogenerated credentials, infostealer logs, and other data leaks.

- Darkweb sellers call combolists “logs” for marketing purposes, to make it seem like fresh and valid data.

Reality:

- When a seller claims that combolist was obtained from infostealer logs, it may simply be an attempt to increase the value of the data. In most cases, these combolists are simply recycled or repackaged old data.

A real infostealer log is more than just a login and password

Why are they often misidentified

On the darkweb, threat actors can sell ULP-file or combolist under the guise of “infostealer logs”, but in reality, a full infostealer log would typically contain:

- HTTP cookies.

- Local files from the disk, for example cryptocurrency wallets, or desktop files. Browser autofill dump.

- System information including IP address, and hardware details

- Active sessions for applications such as Telegram, Steam, Discord, etc.

Reality:

If only logins and passwords are being sold, this is not an infostealer log in the classical sense, but rather the result of the work of an infostealer or a composite database. The following is a table comparing the key differences between infostealer logs and combolists/ULP files.

| Aspect | Infostealer Logs | Combolists / ULP Files |

| Source | Directly from infected devices via infostealer malware. | Aggregated from infostealer malware logs, database leaks, reused data, or autogenerated dumps. |

| Data Format | May include formats like ULP, JSON, or raw folder dumps. | Typically in list format (email:password), ULP, or plain text dumps. |

| Contents | Full digital footprint: credentials, cookies, browser autofills, system info, cryptocurrency wallets, messenger sessions such asTelegram, Discord, Steam, etc. | Mostly credentials (login:password pairs), often lack context or supporting data. |

| Freshness & Validity | Often fresh and valid, collected in real-time during a infection session. | May be outdated, reused, or faked; not guaranteed to be from a real infection. |

| Marketing Confusion | Rarely misrepresented, true infostealer logs are sold at a premium. | Often mislabeled as “logs” for marketing, even if they are not genuine infostealer logs. |

| ULP Confusion | ULP is a format used by some infostealer malware, but not all ULP files are genuine stealer logs. | ULP can be created from various sources, not just infostealer infections. |

| Misconception | Genuine infostealer logs are often diluted or faked in resale. | Many combolists are falsely advertised as stolen data from infostealer logs. |

| Key identifiers | The presence of cookies, local file paths, session tokens, IP addresses, and system information. | Absence of contextual metadata, usually just plain login credentials. |

Why Combolists and ULP Files Are Unreliable Indicators of Compromise

Based on their key difference and structure, we can surmise that the main problem using combolists or ULP files as sources is that they are a secondary, and often unreliable, source of compromised information.

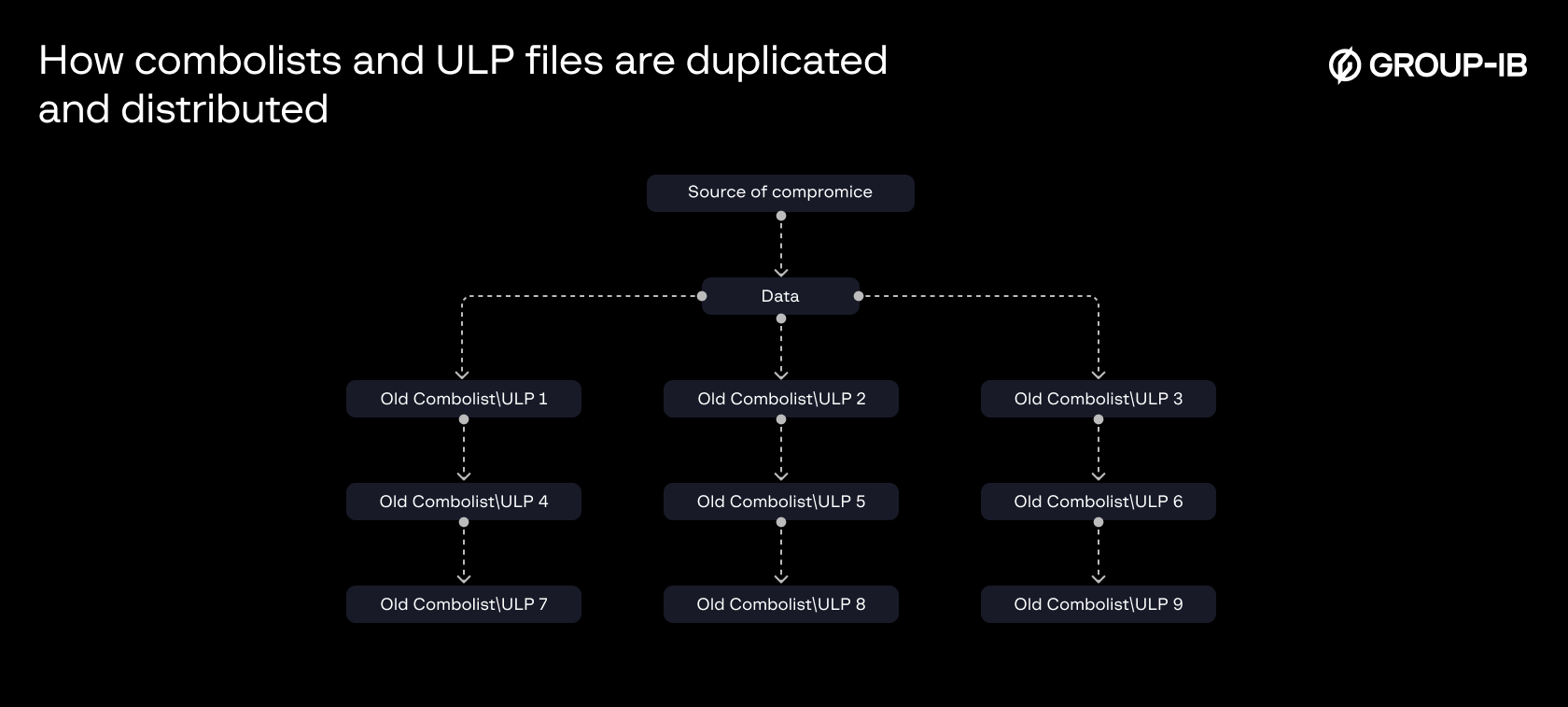

Problem 1: Combolists and ULP Files as Secondary Sources of Compromised Information

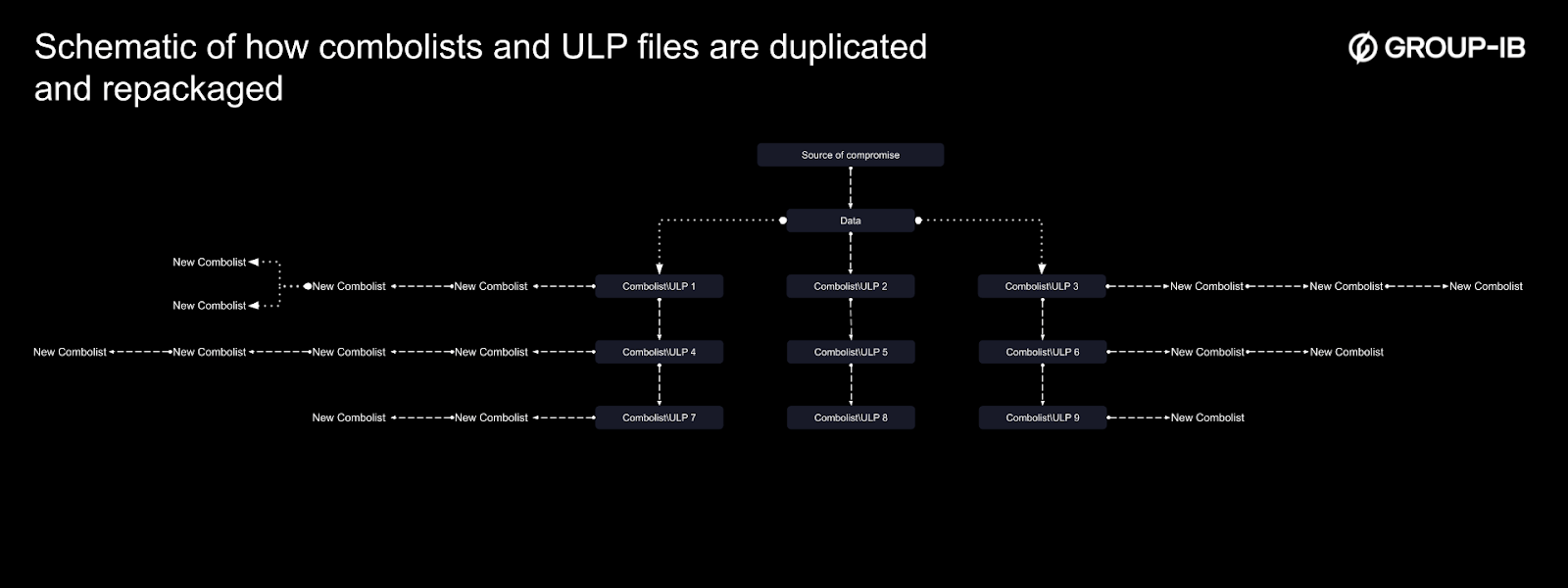

Secondary sources refer to data that was originally compromised elsewhere — such as from a database breach or a stealer log — but has since been duplicated and redistributed across countless combolists. These lists are continuously regenerated by various attackers, often without verification or context, leading to widespread and uncontrolled proliferation of the same credentials. The following is a schematic that illustrates how this occurs.

Figure 6. A schematic of how combolists and ULP files may be duplicated and distributed.

Over time, these combolists become outdated and are recycled again to create yet more variations. The schematic below illustrates how this process unfolds.

Figure 7. A schematic of how combolists and ULP files may be duplicated and repackaged.

At the same time, there is no way to know how much time has passed between the initial compromise of a user—whether through an infostealer or a database breach—and the eventual appearance of their data in a combolist or ULP file.

Often, the file is not taken from a fresh infostealer log or database, but rather from older combolists, ULP files, or even large-scale data collections. The most infamous sources frequently used by attackers include:

- Collection #1–5

- Naz.Api

- Antipublic

- COMB (Compilation of Many Breaches)

- CitoDay

After the attacker borrows data from a source, they may rename the file, creating the illusion of a “new file” or ”new leak”. Since there is no standardized method for renaming files among attackers, the file names are extremely chaotic, and vary based on the attacker’s preferences. That being said, attackers may choose to follow some naming conventions most commonly used within their community, such as:

- By domain country of email addresses,for example: USA, DE, FR, RU, etc.

- By the number of lines in the combolist, for example: 32K, 18.2M, etc.)

- By domains of email addresses, for example: Gmail, Yahoo, Proton, etc.

- By the site for which these credentials may be suitable.

- By the purpose of an email address, for example: personal, government, corporate, etc.

- By whom this combolist was created, typically the alias of the threat actor or name of the telegram channel.

- By stated date of data, for example “March 2025”.

- Moreover, often a phrase like “Fresh”, “High-quality”, “NEW”, “Private data” or timestamp can be added to the file names to draw attention and increase its appeal.

An example of a name partially derived from the naming convention above that attackers might use for their files would be:

“100M_GOVERMENT_USA_HIGH_QUALITY_FRESH_COMBOLIST_ULP_STEALER_LOG_MARCH_2025_BY_@THREAT_ACTOR_X”.txt”

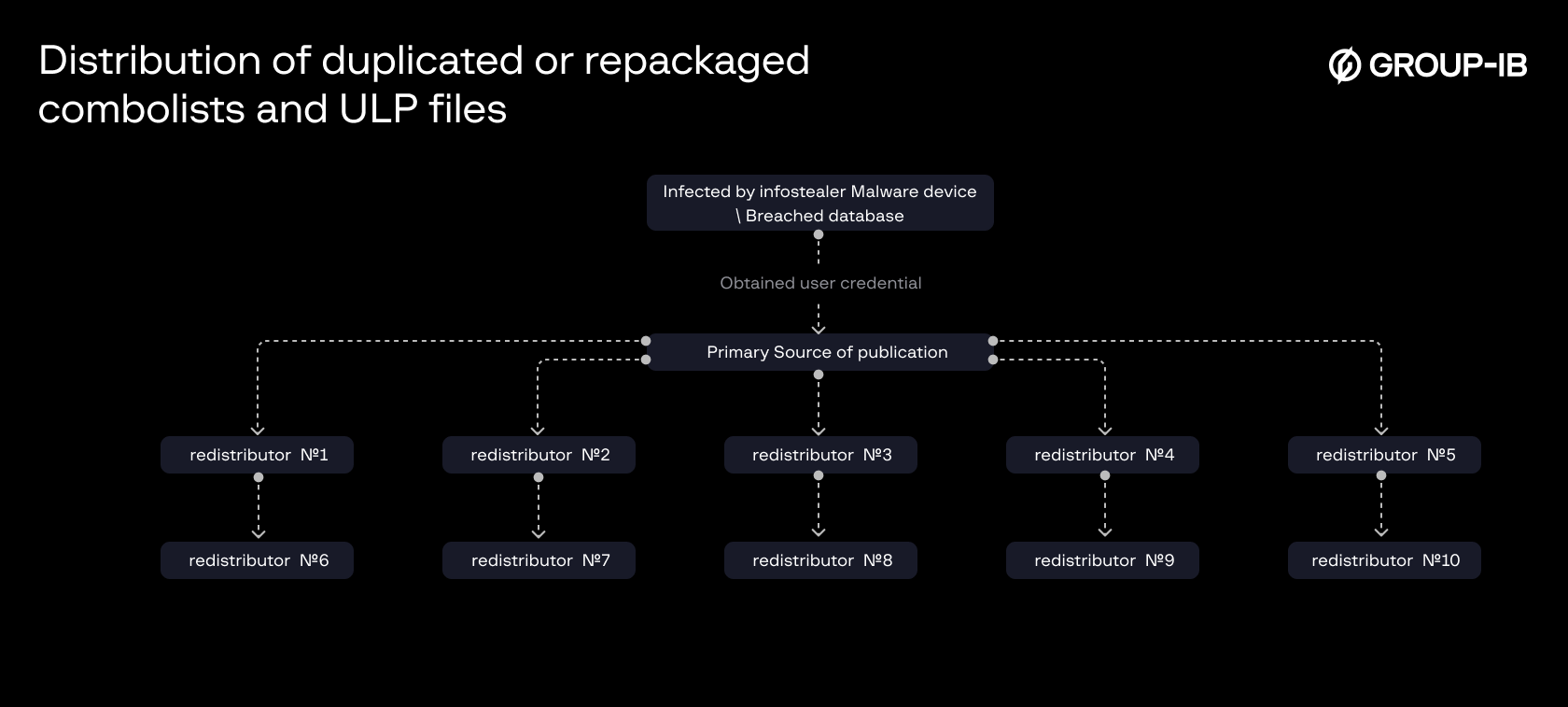

Thus, the same data, sometimes fake, is endlessly repackaged and passed from file to file, spreading across multiple sources under different names.

Figure 8. A schematic of how duplicated or repackaged combolists and ULP files may be redistributed.

When collecting only processed information—such as combolists or ULP files—from sources that merely reassemble and redistribute compromised data, several serious issues arise:

- Loss of context: the true cause, date, and origin of the initial compromise of the user data is obscured.

- False assumptions: Victims may mistakenly believe their systems were recently breached, even if the leak was outdated or recycled.

- Desensitization: Continual alerts of historical intrusions can lead to user fatigue. When a genuine, current breach occurs, it may be ignored, which may result in increased risk.

- Dependence on intermediaries: Situational awareness becomes entirely reliant on the speed and accuracy of third-party actors responsible for compiling and disseminating collected data. There is no guarantee of timeliness or reliability.

It may appear self-evident, yet is often overlooked: the information found in a password dump or login archive must have originated from a specific compromise. It does not materialize out of thin air. For this reason, Group-IB analysts emphasize the importance of prioritizing the identification and monitoring of original breach sources—not merely the ecosystems that circulate secondary data artifacts.

Of course, some may argue that collecting all available data from every possible source provides a more complete picture of how compromised information spreads. There is some truth to this as distributors, due to their vast numbers, can occasionally publish data in combolists or ULP files before it is detected by researchers, analysts, or cybersecurity companies. Group-IB has tools capable of identifying when compromised data is secondary in nature.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that secondary data is often inaccurate or misleading. For that reason, the ideal approach is to focus on identifying and monitoring primary sources of compromise, rather than relying on the variable reliability of those who reassemble and redistribute leaked information. Additionally, a significant challenge with many reassemblers is the poor quality and inconsistency of the data they produce.

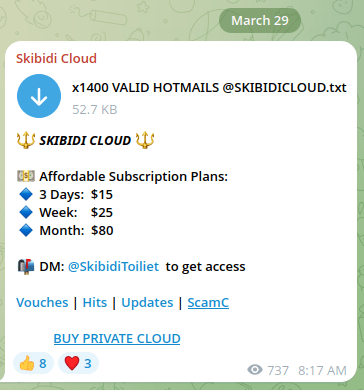

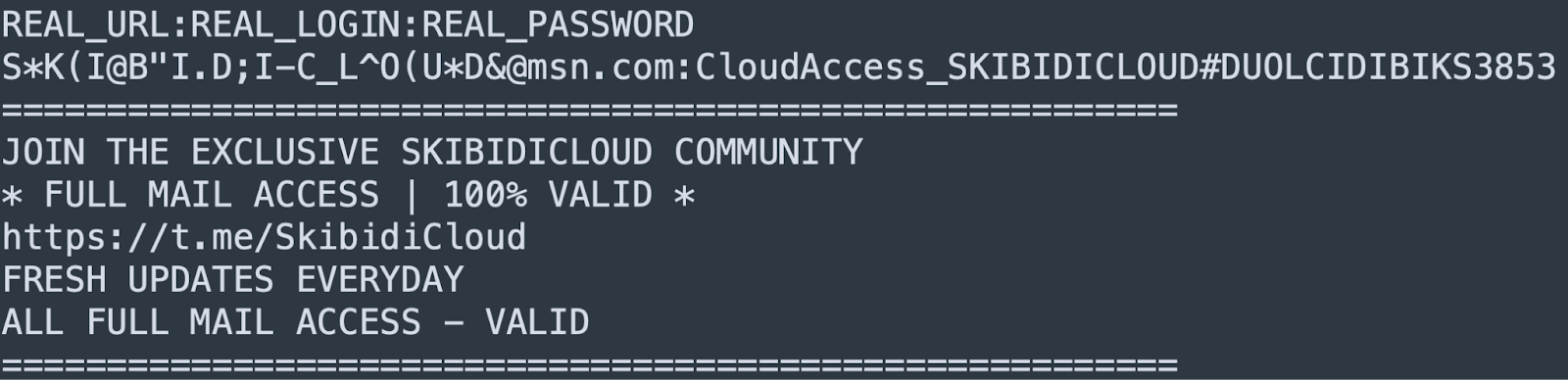

Problem 2: Low Quality, Unreliable, or Artificially Generated Combolist/ULP Data

Often, the contents of a combolist or ULP file can be highly unreliable. The data may be entirely autogenerated, or it may include a mix of real and fake entries, making it difficult to verify its authenticity. In some cases, legitimate data is falsely labeled as valid credentials for specific websites, but upon inspection, these claims often prove to be inaccurate.

The reliability or authenticity of the data can vary from case to case, and file to file. The following example was taken from one of the published combolists in a Telegram channel:

Figure 9. A screenshot of a message posted on a Telegram channel on subscription plans to gain access to combolists.

Figure 10. A screenshot of the text file from the Telegram channel.

It is ironic that the last line in the file is a generated email, followed by a channel disclaimer promising fresh and 100% “quality data”.

Combolists and ULP files can also contain more subtle forms of deception, as illustrated by a case encountered by a Group-IB analyst. A line from the ULP claimed that the analyst’s login and password were compromised in a well-known social network. At first glance, the data appeared genuine:

- The mentioned social network and its login URL were real.

- The e-mail address existed and did, in fact, belong to the Group-IB analyst.

- The password was valid and had previously been used by the analyst with that email address.

However:

- The analyst had never registered in that social network, which is also confirmed by the platform’s password recovery service.

- Moreover, the analyst recalled using that email address and password combination only once on a small forum dedicated to video games back in 2011.

It was later discovered that the database of that forum had been stolen and published in 2015. From there, the data circulated on the dark web until eventually, an attacker repackaged it and included it in a combolist, falsely labeling it as a breach of the social network.

In this case, each individual data point was real, but the context was entirely fabricated. The attacker had misrepresented an old leak of a gaming forum as a leak of users of a well-known social network. Such issues with the authenticity of combolists and ULPs are commonly encountered in practice, where an entire line, or parts of it, may be fabricated, for example:

🔴FAKE_URL🔴:🔴FAKE_LOGIN🔴:🔴FAKE_PASSWORD🔴

🟢REAL_URL🟢:🔴FAKE_LOGIN🔴:🔴FAKE_PASSWORD🔴

🔴FAKE_URL🔴:🟢REAL_LOGIN🟢:🔴FAKE_PASSWORD🔴

🔴FAKE_URL🔴:🔴FAKE_LOGIN🔴:🟢REAL_PASSWORD🟢

🟢REAL_URL🟢:🟢REAL_LOGIN🟢:🔴FAKE_PASSWORD🔴

🟢REAL_URL🟢:🔴FAKE_LOGIN🔴:🟢REAL_PASSWORD🟢

🔴FAKE_URL🔴:🟢REAL_LOGIN🟢:🟢REAL_PASSWORD🟢

Of course, stealer logs can also be intentionally falsified or collect unreliable information. Imagine, for instance, accidentally entering your email address in the user name field on some sites. But even considering all the issues related to data reliability or unreliability, it is important to return to the fundamental problem with combolists and ULP – their secondary nature.

To illustrate this, we examine a notable case involving a distributor of secondary or unreliable data in the form of combolists and ULP files, an attacker associated with the AlienTXT telegram channel.

AlienTXT Case: How a Low-Quality Reassembler and Seller of Secondary and Fake Data Became Famous

AlienTXT and its Telegram channel became widely known in February 2025 after a cybersecurity researcher reported that the AlienTXT Telegram channel contained 23 billion lines of user data from stealer logs. As a result, the so-called “AlienTXT Collection” came into circulation on the darkweb.

Figure 11. A screenshot of the cover image or profile of the AlienTXT Telegram channel.

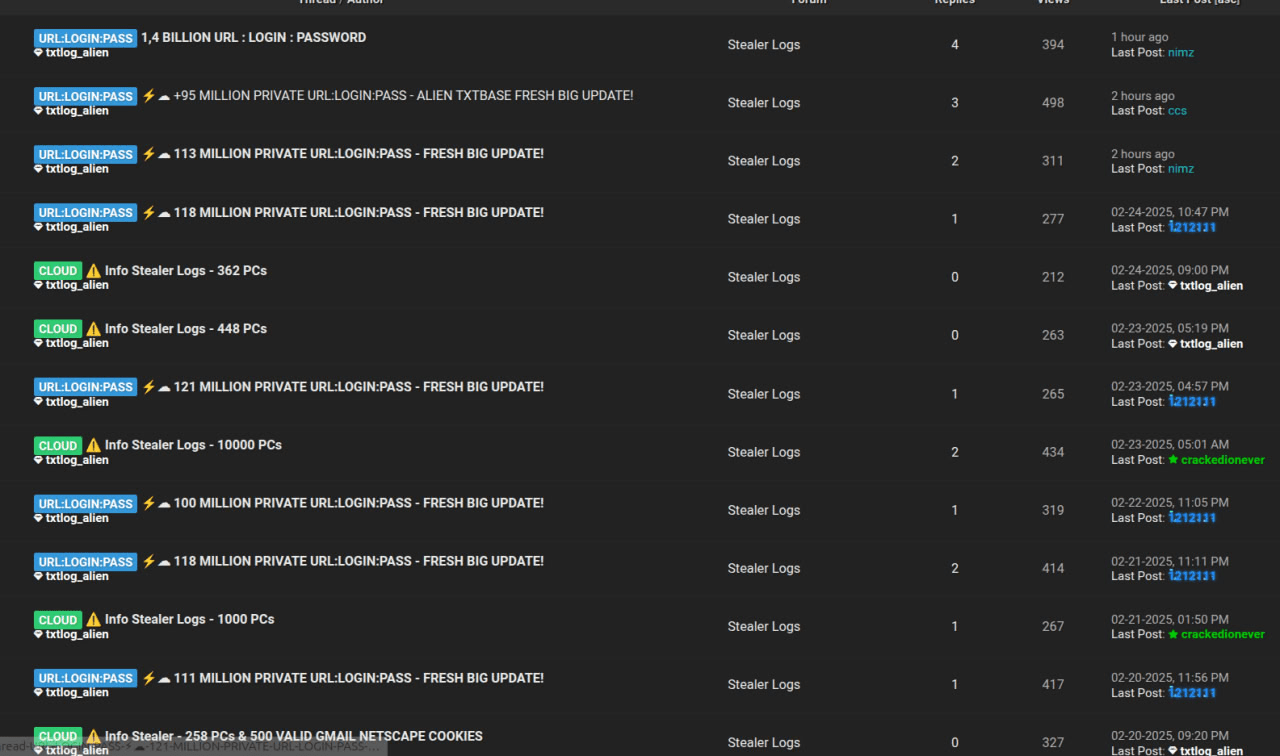

Figure 12. A screenshot of posts made by AlienTXT on a dark web forum.

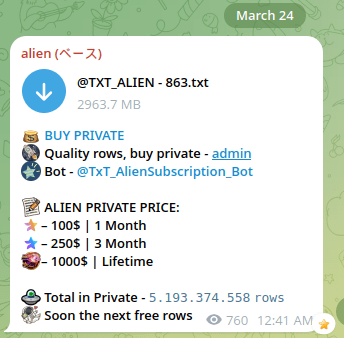

Figure 13. A screenshot of messages posted by AlienTXT on Telegram.

After analyzing each file available on this Telegram channel and on its republications in the dark web forum, it turns out that this data contains a lot of very old information from old or previously circulated combolists, stealer logs, and ULP files. There were also many instances of auto-generated information.

At this point, it is important to emphasize again that AlienTXT publishes ULP files, not stealer logs. Only on a few occasions did AlienTXT publish infostealer logs on the dark web forum, but even then, in line with a fraudulent pattern the logs were taken from other sources. The only modification made was replacing the original LummaC2 infostealer name with the nickname AlienTXT.

The Lifecycle of Compromised Data: How Stealer Logs Evolve into Combolists, ULP Files, and AlienTXT Distributions

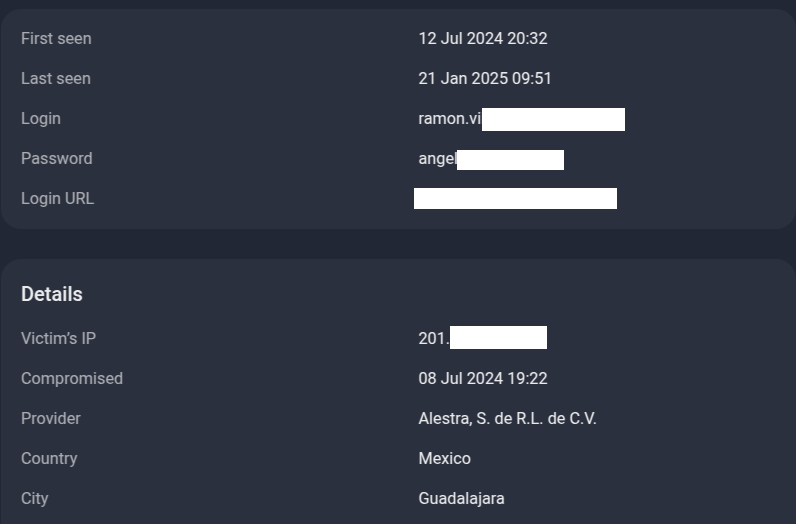

In the following real-world example (Figure 14), we have a user using a login ID of “ramon.vi[redacted]”, and his password “angel[redacted]”. According to the published logs, this user’s device was infected with an infostealer malware on 8 July, 2024. Post-infection, the user’s information, including email addresses and multiple passwords, was compromised and began appearing in infostealer logs uploaded to underground cloud storage.

Figure 14. A screenshot of Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence platform, which shows the published infostealer log of a single user, revealing the email address and password, as well as when the device was infected with an infostealer malware.

But what happens to the email address/login and passwords of the user “ramon.vi[redacted]” after the initial compromise in summer 2024? The data begins its endless circulation through combolists and ULP files, or collections of this data. The following is just a small example of the files from July 2024 that contained data associated with the user “ramon.vi[redacted]”: :

- COMBOLIST_merge.csv

- gmail_2.txt

- gmail (9).txt

- [80.543.064] PART V.txt

- 25kk USA BD.txt

- MailPass_Database_22kk.txt

- [EmailPass]Result 22kk.txt

- ULP @FATETRAFFIC 18KK.txt

- 215k Gmail UHQ Combolist.txt

- ULP @FATETRAFFIC 35KK.txt

- Combo @FreeUhqCombo.txt

- 18m_URLPW_LB.SB_Part_2-30.txt

- 67m_mailpass_by_leakbase.io.txt

- BY TELEGRAM @TXT_ALIEN – 856 – 46711787.txt

And finally, the same old data associated with “ramon.vi[redacted]” was published by TXT_ALIEN on 20 March 2025 in the file “BY TELEGRAM @TXT_ALIEN – 856 – 46711787.txt” as part of what TXT_ALIEN calls “136 million private ULP data”.

![Figure 15. A series of screenshots of posts made by TXT_ALIEN on 20 March 2025, which included data associated to “ramon.vi[redacted]”.](https://www.group-ib.com/wp-content/uploads/unnamed-2025-07-04t152752.179-min.png)

Figure 15. A series of screenshots of posts made by TXT_ALIEN on 20 March 2025, which included data associated to “ramon.vi[redacted]”.

Referring to the screenshot above (Figure 15), we can see data associated with the user “ramon.vi[redacted]”, which on first appearance seems new data from the user’s compromised device. But upon closer inspection, we can clearly see that the data was compromised in July 2024, and the attacker TXT_ALIEN, published a ComboList with this data as early as March 2025. The specified ComboLists and ULP files contain only processed information from “ramon.vi*”, recorded back in Summer 2024.

It is safe to assume that “ramon.vi[redacted]” would prefer to know about the compromise of his data at the moment of its compromise, and not at the moment when this data reached the ComboLists and the ULP file from AlienTXT.

Therefore, schematically, the following situation arose: when the device and user data were compromised back in July 2024, the data (we emphasize once again – without the presence of new lines) began to spread across multiple files in the assemblies of combolists\url lists, and were ultimately reworked, and the notorious AlienTXT:

![Figure 16. A flowchart of how the data from the user “ramon.vi[redacted]” spread across multiple files that were repackaged and redistributed.](https://www.group-ib.com/wp-content/uploads/04-infographic-3-min.png)

Figure 16. A flowchart of how the data from the user “ramon.vi[redacted]” spread across multiple files that were repackaged and redistributed.

In addition to the secondary nature of the data, another problem is the presence of non-existent data and bad line structure, which can be found in the AlienTXT publication. Specifically, many lines fail to adhere to the standard URL:LOGIN:PASSWORD format, which undermines the data’s integrity, and further complicate efforts to analyze or validate the breach.

- URLs: javascript:profile(document.getElementById(‘regForm’));:kero:j@4Nbc2DqEmmePh

- Email addresses: https://account.activedirectory.windowsazure[.]com/passwordreset/register[.]aspx:Щ…Ш§Ш°Ш§:ЩѓШ§Щ†ШЄ:Ш±ЩЉШ§Ш¶ШЄЩѓ:Ш§Щ„Щ…ЩЃШ¶Щ„Ш©:ЩЃЩЉ:Ш§Щ„Щ…ШЇШ±ШіШ©:Ш§Щ„Ш«Ш§Щ†Щ€ЩЉШ©Шџ:*************

- Passwords: https://grp01[.]id[.]rakuten[.]co[.]jp/rms/nid/regist1:比如пС:*********

Is it really necessary to explain the obvious risk in paying for supposedly “high-quality” data, especially when that data may be outdated, repeatedly compromised, or even fabricated? The illusion of value does not justify the purchase if the data is unreliable.

Some might argue that AlienTXT gave this data away for free precisely because it’s old, and that fresh data can only be obtained through a subscription.

That may be true. However, it’s also worth asking: if the freely available data was gathered from other sources, why should we assume that the paid data originates from the Telegram channel operator’s own breaches?

If this is simply resale, where users are charged for the convenience of having data aggregated and repackaged, then, as we’ve emphasized many times, it becomes critical to trace the original sources of compromise. Blindly trusting distributors, regardless of how well-organized their service appears, is a poor substitute for proper attribution and verification.

Within the context of the report, it seems like there is little value in downloading and analyzing everything that AlienTXT (or any other source like AlienTXT) offers for free download or purchase, to calculate the percentage of what data is taken from old compromises, what does not exist, and so on. A more effective approach is to examine the attacker’s own statements and claims, which can provide insights into the origin, purpose, and credibility of the data being distributed.

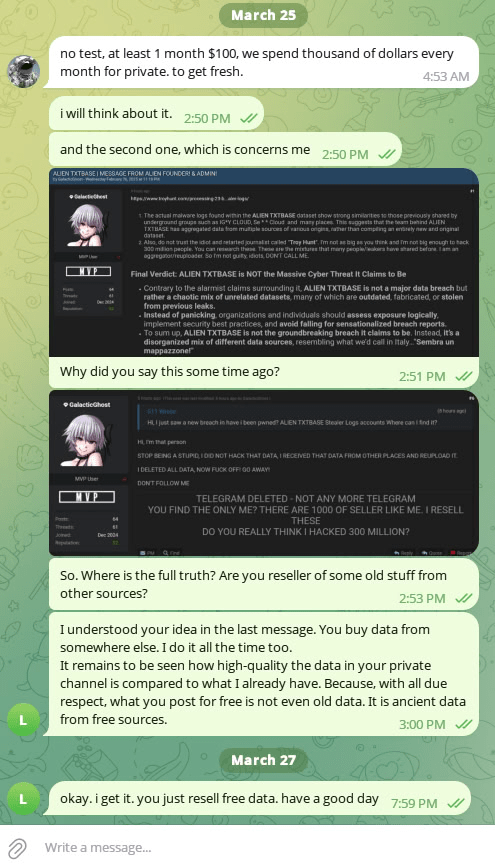

Statements by AlienTXT

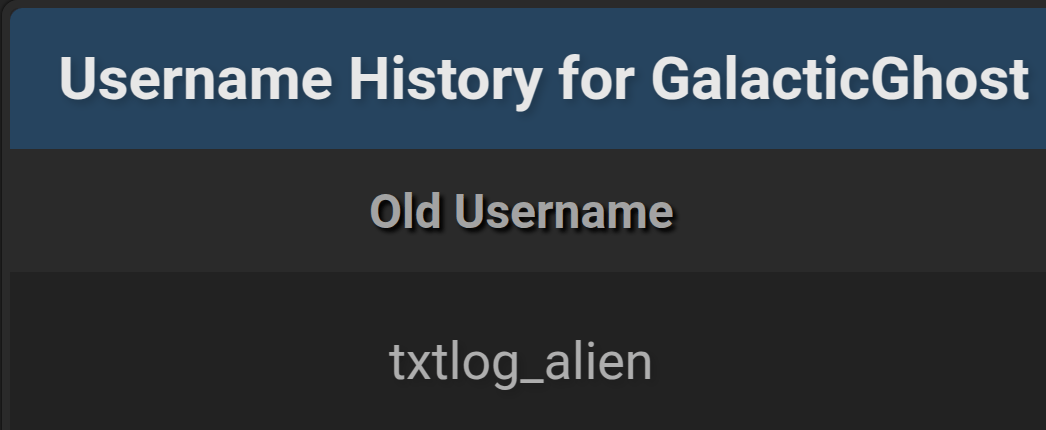

Following the publication of a lengthy article by a researcher about the “great threat” posed by “AlienTXT”— and emphasizing the billions of user records allegedly contained in the ULP files shared via his Telegram channel — the operator of the AlienTXT channel changed his nickname from txtlog_alien to GalacticGhost on BreachForums.

Figure 17. A screenshot of the BreachForums profile of txtlog_alien, which changed to GalacticGhost soon after the publication of an article about AlienTXT by a cybersecurity researcher.

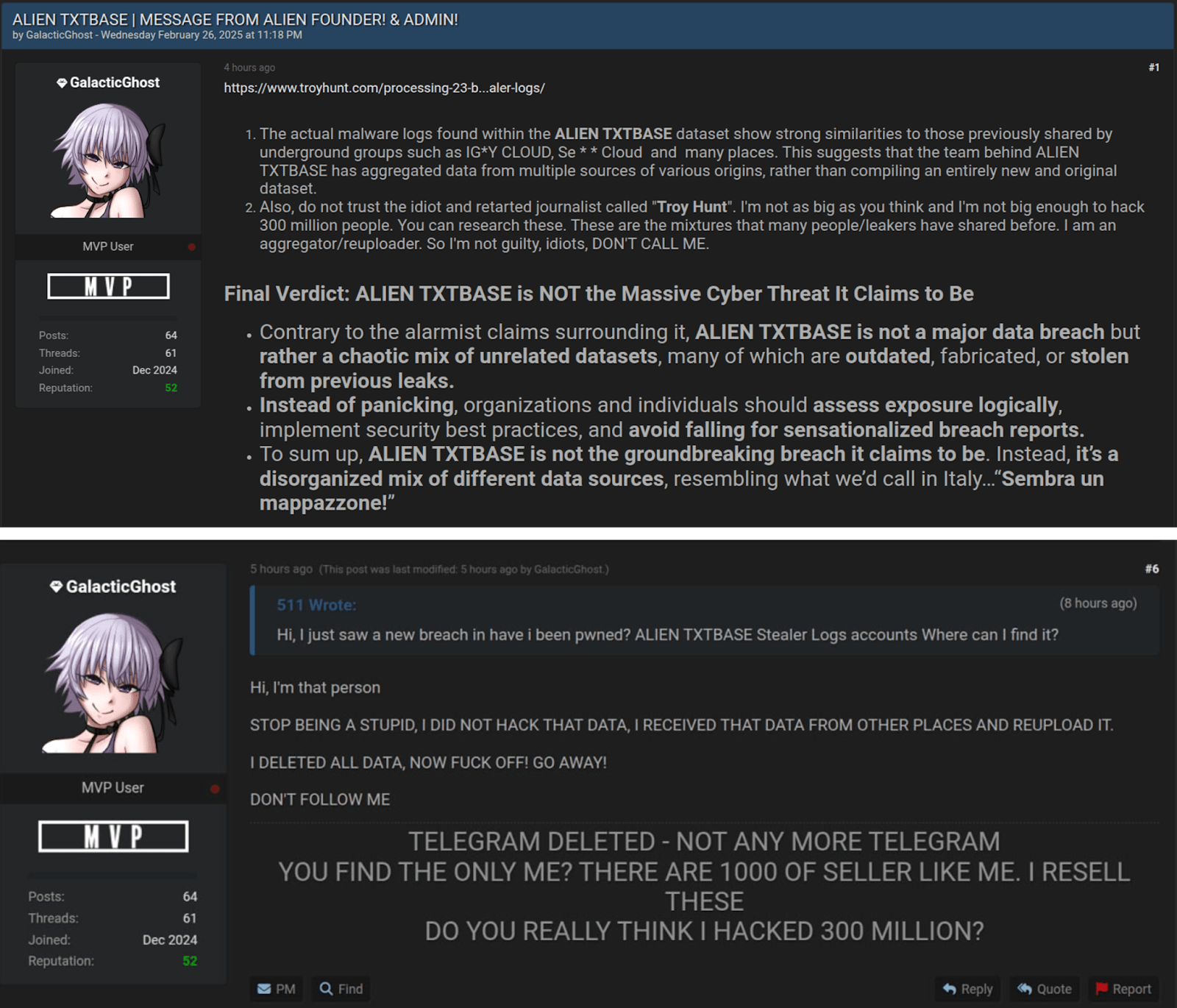

Motivated by the fear of the heightened attention after the researcher’s article attracted so much attention to him, AlienTXT deleted all his public Telegram channels. AlienTXT also published the following statements on the BreachForums, which further validates our assessment regarding the low reliability and relevance of the data that AlienTXT distributed:

- AlienTXT is not the author and the original source of any attacks;

- AlienTXT only resells data much of which is already publicly available;

- AlienTXT repackages old, previously compromised data into new files, presenting them as fresh leaks.

Figure 18. A series of screenshots from BreachForums of GalacticGhost attempting to distance and discredit his former self (AlienTXT).

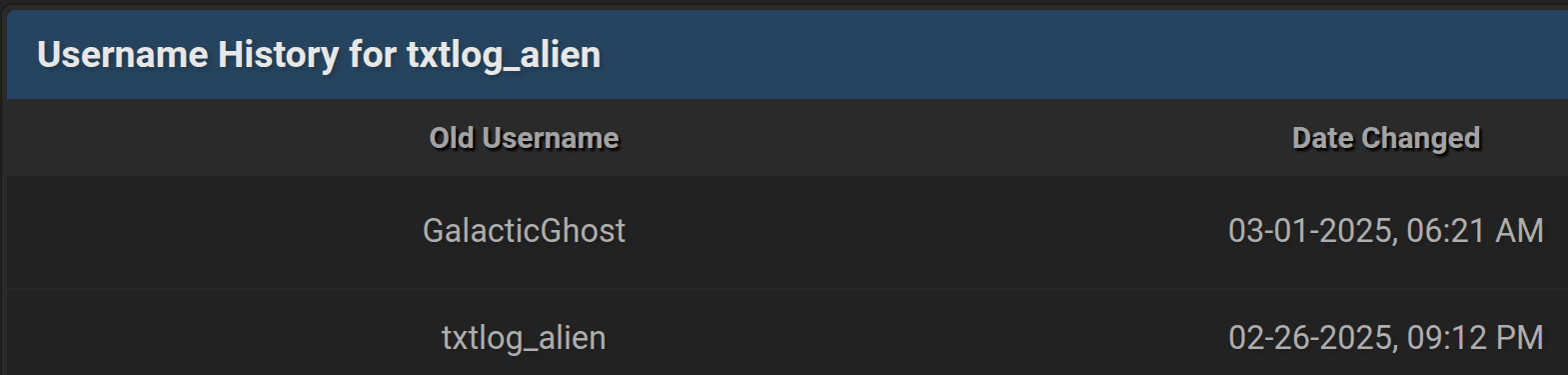

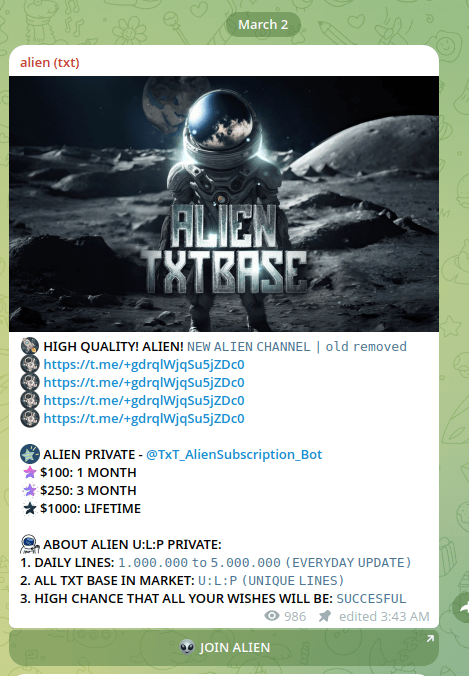

Ironically, on 1 March 2025, GalacticGhost — the threat actor formerly known as AlienTXT—reverted to his previous nickname on BreachForums, and promptly deleted all of the messages he posted discrediting AlienTXT, and relaunched his Telegram channel.

Figure 19. A screenshot of the username history of txtlog_alien on BreachForums.

Figure 20. A screenshot of the new Telegram channel launched by AlienTXT.

It’s reasonable to assume that the scammer saw an opportunity to profit from the publicity generated by the researcher’s article. Among many users on dark web forums, a narrative quickly emerged: “Wow, I read about a massive, high-quality data collection — I want it!” Yet few took the time to question the origin or credibility of the data. This once again highlights that even within cybercriminal communities, there is often a low level of awareness regarding data quality and authenticity.

That said, let’s give AlienTXT the benefit of the doubt — perhaps he was genuinely alarmed by the sudden surge of attention, unintentionally incriminated himself, and in reality, both he and his Telegram channel are legitimate sources of compromised user data:

Chatting with AlienTXT

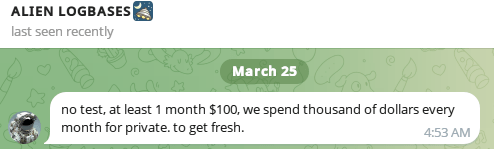

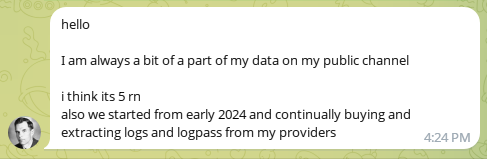

Posing as a potential subscriber, Group-IB analysts contacted AlienTXT in an attempt to obtain any details.

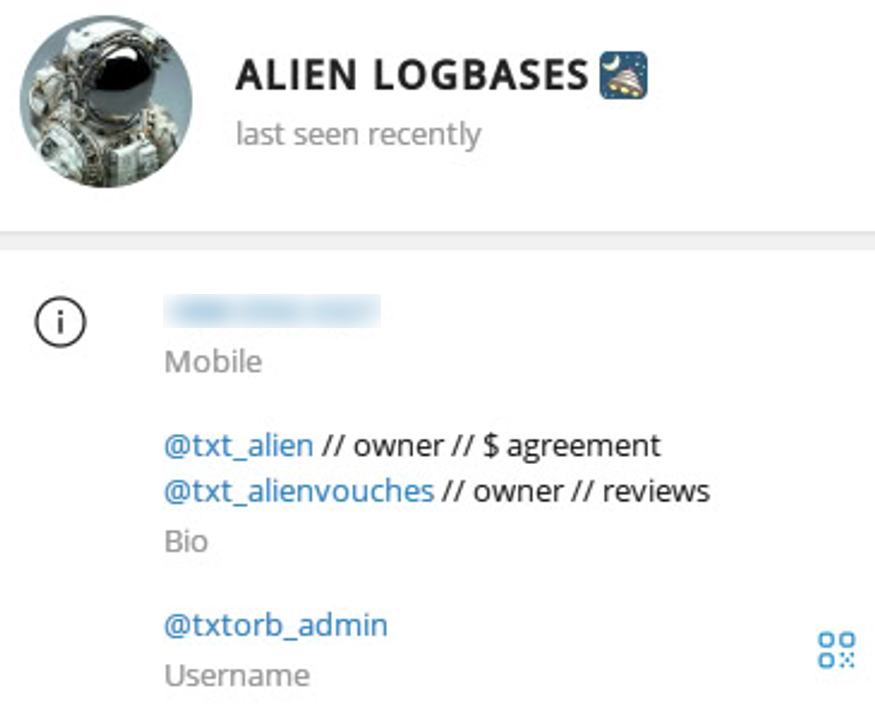

Figure 21. A screenshot of contact information of AlienTXT.

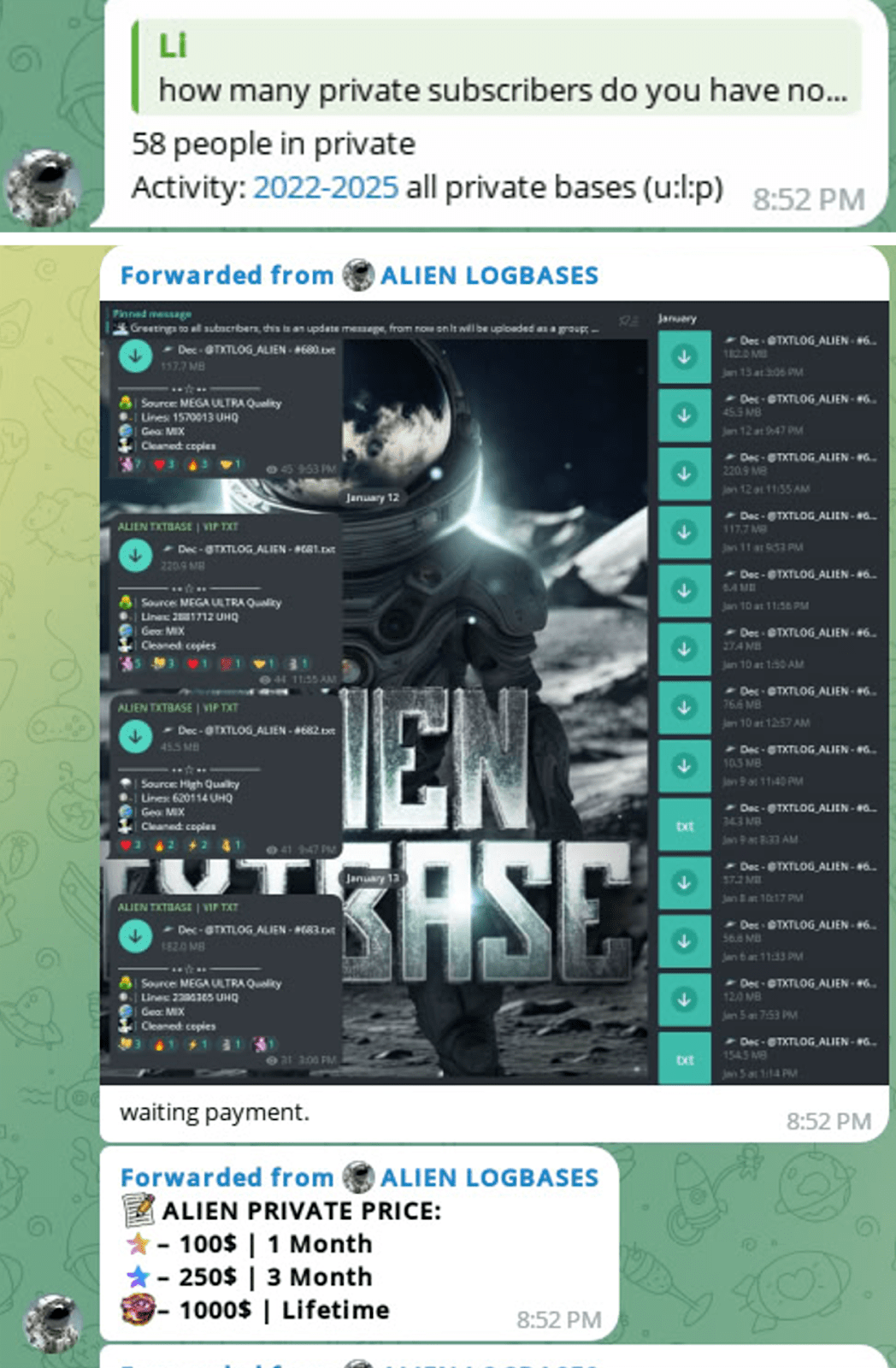

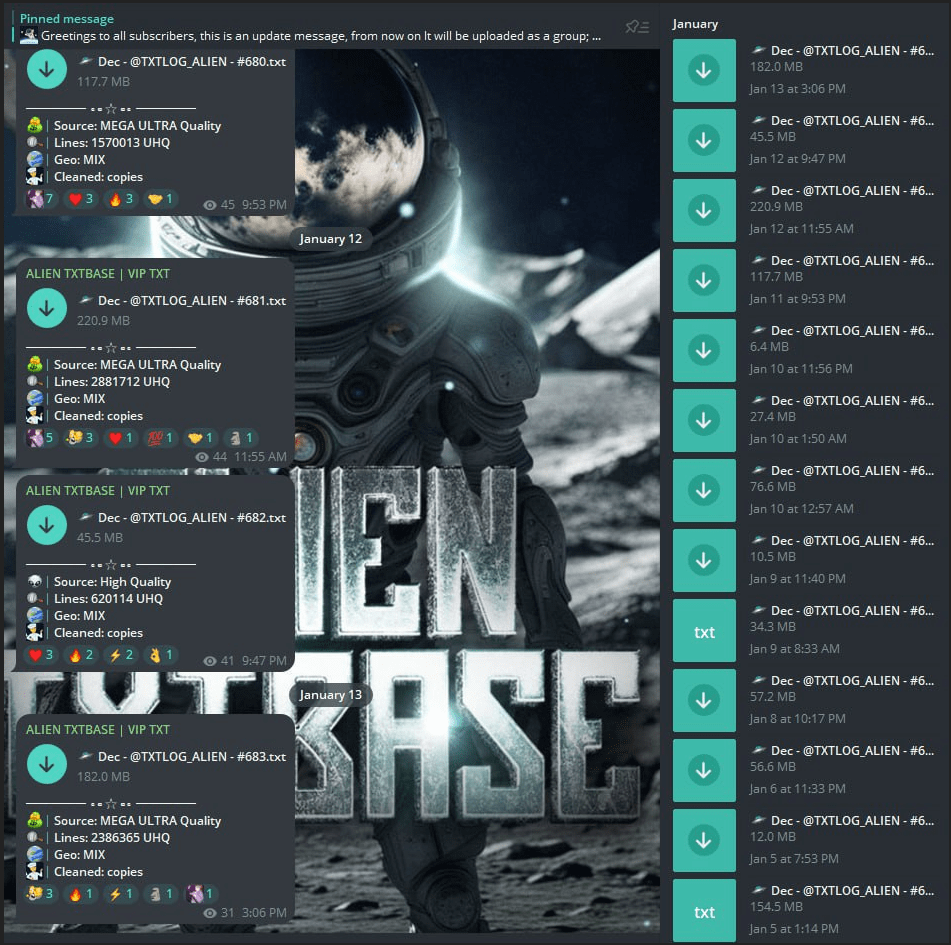

According to AlienTXT, there are about 58 people in the private group as of March 2025. The number of views of his messages in the private group more or less confirms this information.

Figure 22. A series of screenshots of messages between Group-IB and AlienTXT.

Figure 23. A clearer screenshot of the information shared by AlienTXT with Group-IB.

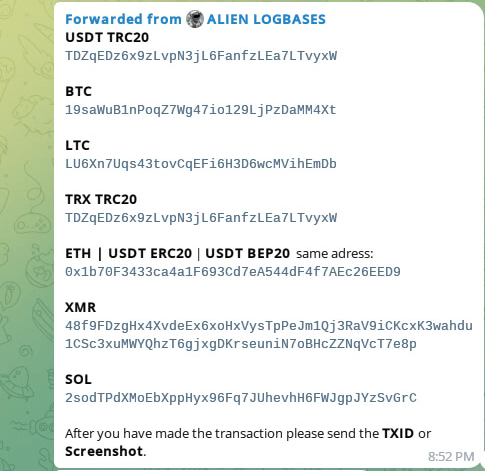

AlienTXT also provided a number of crypto wallets that can be used to pay for access to a private Telegram channel.

Figure 24. A screenshot of a number of cryptocurrency wallets that subscribers could pay for access to the private Telegram channel.

For example, according to blockchain data, the Bitcoin wallet associated with AlienTXT received approximately 0.05771821 BTC between May 2024 and March 2025—equivalent to around $5,000 USD as of March 24, 2025. Not a bad return for repackaging and selling old, publicly available data.

We reached out to AlienTXT with a simple request: to provide a few sample lines from his latest, supposedly fresh files shared via his private channel—just enough to verify their quality and recency. His response was a firm no. Sticking to a “pay or leave” model, AlienTXT refused to offer any samples. He also claimed that he spends thousands of dollars each month acquiring private, fresh data—though without proof, such claims remain unverifiable.

Even by his own admission, it’s clear that if AlienTXT is indeed acquiring data, he is functioning as a distributor, not the original source. Recognizing that the discussion was reaching an impasse, Group-IB analysts posed a direct question without any reaction or answers from AlienTXT:

Figure 25. A screenshot of the conversation between Group-IB and AlienTXT.

Based on all that we have seen so far, as well as from the conversations we had with AlienTXT, we can surmise that:

- AlienTXT publishes data reassembled from other sources for free, which often turns out to be either very old, generated, or fake data.

- AlienTXT states that a private telegram channel contains “new and fresh data” but refuses to provide samples and evidence. Apparently, in his opinion, the evidence is the data he has published for free, which he often calls “fresh” and private data.

- AlienTXT personally made a number of incriminating statements that he is simply reassembling old free data. But apparently at some point, realizing the opportunity to make money on the fame that the researcher gave him, he changed his mind, deleted all his confessions, and restarted the project. AlienTXT ignores all questions related to his past confessions.

Another example of threat actors and Telegram channels with old combolist\ULP data

There is no shortage of threat actors operating Telegram channels that share material similar to AlienTXT. This ecosystem enables an endless stream of so-called “new” data breach reports, often citing the same recycled “billions of user records.” In reality, this phenomenon has become commonplace, fueled by the widespread distribution of ComboLists, stealer logs, and ULP files via Telegram.

The examples highlighted below represent some of the most active channels, selected based on their visibility, frequency of activity, and inclusion in notable news coverage and research reports discussing the risks associated with publishing compromised data on Telegram:

Daily Combolists

Dragon Cloud

Ratclouds

Plutonium

Inereal Cloud

iZED KINGDOM

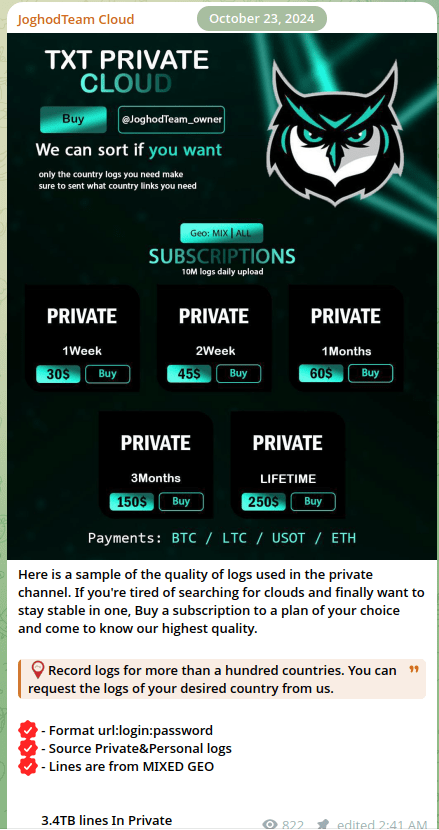

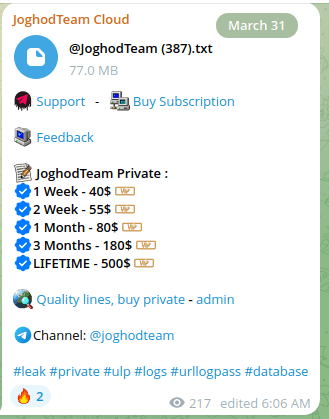

JoghodTeam Cloud

ARES

CAPTAIN KINGDOM

Skibidi Public Cloud

By collecting information from certain Telegram sources, it’s possible to come across daily claims about the compromise of terabytes and billions of user records — often without any verification or confirmation of the data’s authenticity.

- Obtain all free data from such telegram channels.

- Posting the amount of data (Billions of unique data!) and insert threat actor and the word “Collection” at the end.

- Loud headline and news – ready!

This kind of information noise, centered around supposedly massive data leaks heroically “collected” from low-quality Telegram sources (or other data storage locations), can be generated multiple times a week. And, in practice, this is exactly what some researchers do: publish alerts based on outdated, low-quality, or outright false data circulating in dark web spaces.

As we’ve emphasized throughout this article, the real value lies not in simply reporting what is collected and distributed, but in tracing the original source of compromise—determining when, where, and how the breach occurred. Only by identifying the initial compromise points, rather than endlessly recycling secondary information from resellers and aggregators, can we produce meaningful threat intelligence.

What about private telegram channels for distributing combolists and ULP files?

The article has already raised the commonly repeated claim:

“Data in public channels is free because it is old! If you want new private data, buy it!”

But if you reject the counterargument, “How can you advertise the quality of your product with old, fake, or low-quality data?” then let’s put the claim of “high-quality private data” to the test.

As part of the audit, we did not buy private data. Instead, Group-IB analysts tried to contact a large number of popular channels like AlienTXT to obtain samples from private channels. And they always received 3 types of responses:

- Completely ignored;

- “No samples without purchase.”;

- “All samples are available in the free Telegram channel” (someone even added that there is also fresh and high-quality data there).

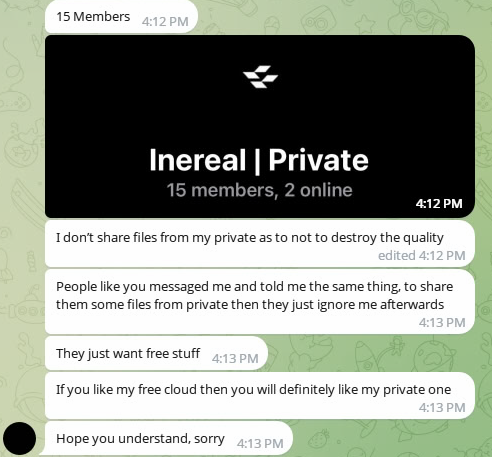

These interactions only reinforce the skepticism around claims of exclusive, valuable private datasets. The following are some of those chats:

AlienTXT

Inereal

Plutonium

JoghodTeam

Shroud

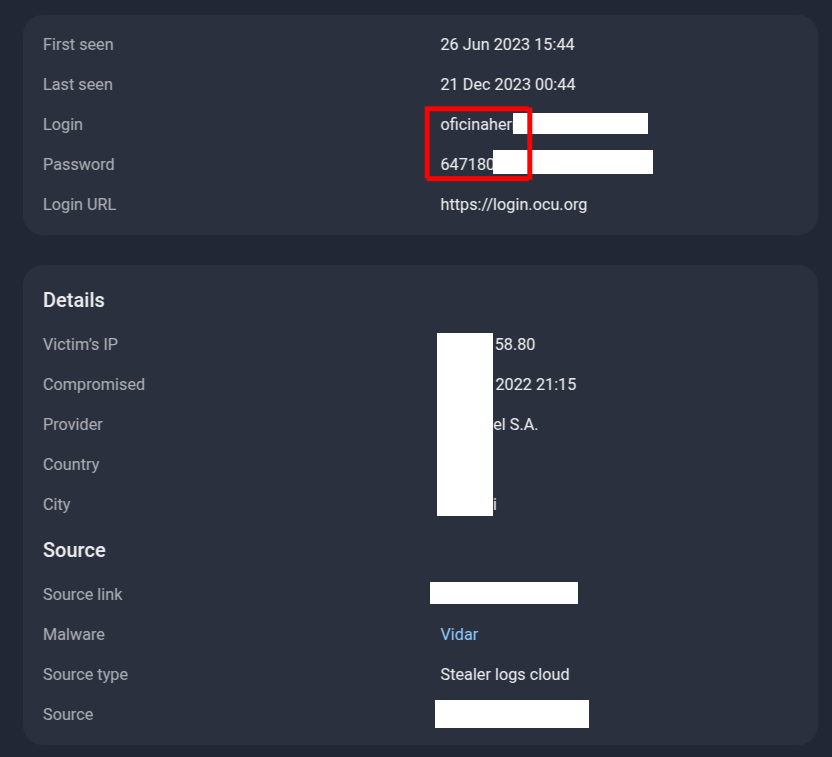

Let’s once again examine the so-called high-quality data promised in these free Telegram channels, that is supposedly intended to convince users to purchase access to private channels. Nearly every such channel includes a description claiming that the free data serves as a sample of the quality available in the private collections.

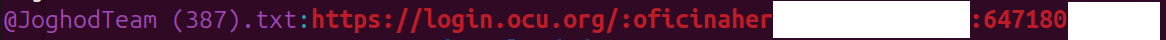

Figure 26. A screenshot of the JoghodTeam Cloud Telegram channel.

We take the most recent free file that is available at the moment:

Figure 27. A screenshot of the JoghodTeam Cloud Telegram channel.

Let’s take any line:

And what do we consistently find when reviewing these so-called “fresh” samples? Time and again, the data being posted in 2025 can be traced back to compromises that occurred as far back as 2022. This repeated pattern further exposes the misleading nature of these channels — promoting recycled, outdated breaches as if they were recent or exclusive.

Figure 28. A screenshot of Group-IB’s Threat Intelligence platform, showing the published infostealer log of a single user, revealing the email address and password, as well as when the device was infected with an infostealer malware.

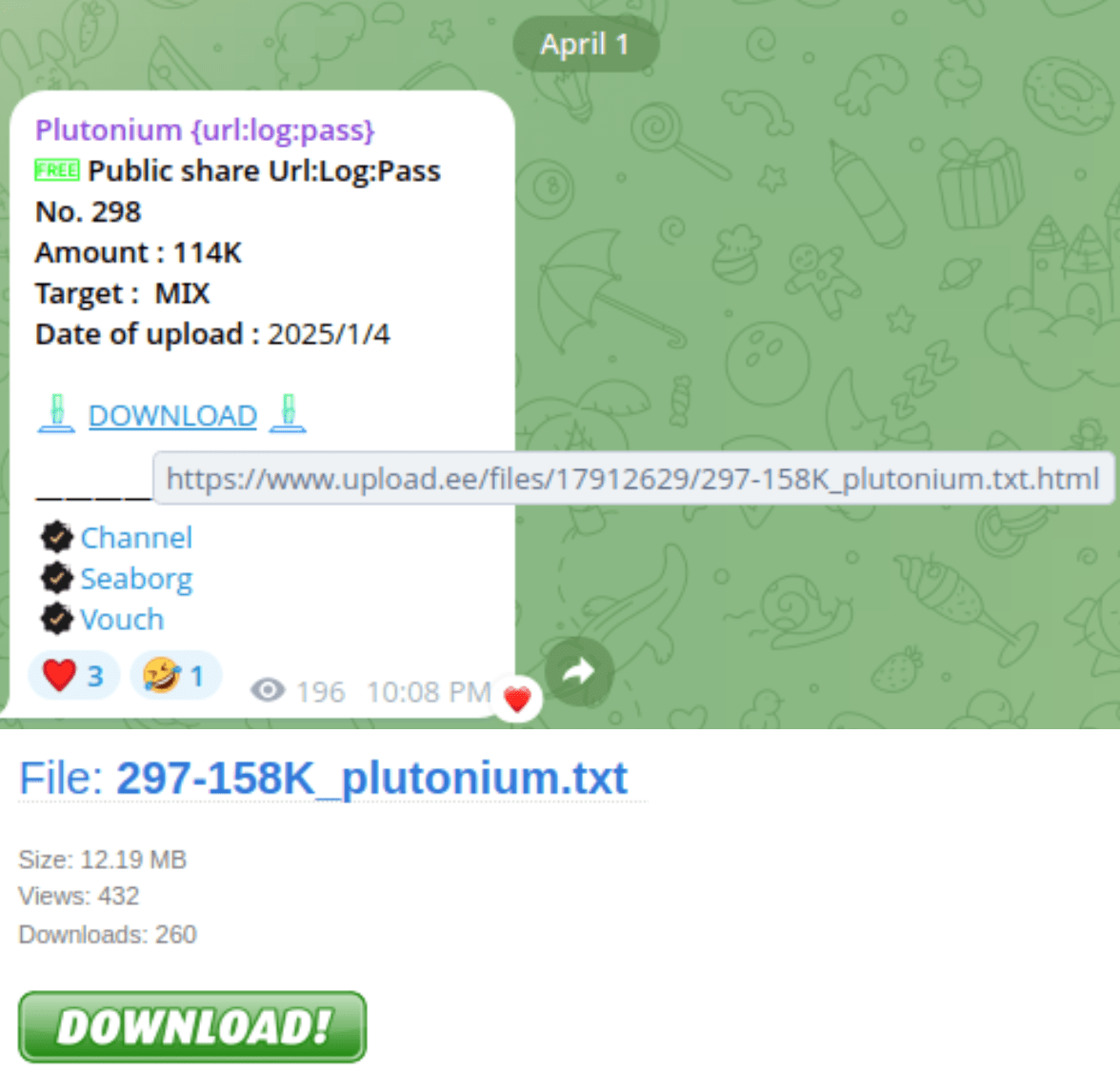

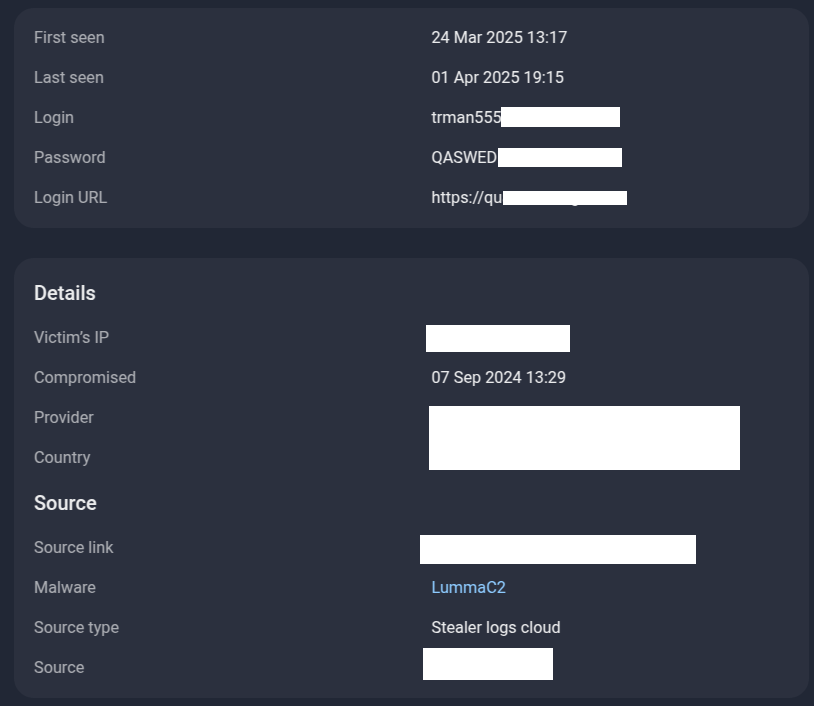

Let’s take another example, this time from the Plutonium channel dated 1 April 2025.

Figure 29. A screenshot of the Plutonium Telegram channel and of its sample data file.

Let’s take “trman555” as an example:

So what do we see? Credit where it’s due—on April 1, 2025, the Plutonium Telegram channel published a file containing many lines that Group-IB had first observed publicly in stealer logs just a month earlier, in March 2025. But the stealer logs also recorded all the information about the user’s device, as well as the date of compromise of the user’s device back in September 2024.

This once again reinforces the core issue with ULP files and ComboLists: they are secondary by nature, no matter how fast the distributor of combolists and ULP files is. And while there are indeed many threat actors on the dark web skilled in repackaging stealer data into more user-friendly formats, no distributor can outpace the point of origin.

Figure 30. A screenshot of a published infostealer log of a single user, revealing the email address and password, as well as when the device was infected with an infostealer malware.

Conclusion

There is no shortage of articles highlighting the massive volumes of user data circulating in Combolists and ULP files. At the same time, many reports have justifiably questioned the quality, freshness, and credibility of that very data. This cycle of sensational headlines followed by fact-checking rebuttals appears destined to repeat indefinitely.

We can expect that some researchers will continue sourcing data from low-quality Telegram channels, darkweb forums, and other sources who are aggregating and collecting this data, regularly shocking the public with claims of “Billions of compromised user records.” And each time, the same critical questions will need to be asked:

“What is this collection? Is the data fresh? Is it reliable?”

Only the names will change — from AlienTXT and Naz.Api to new labels like “Mother of ComboLists”, “Father of ULP Files”, “16 Billion Collection from record-breaking data breach”, or “Threat Actor X Collection.”

To be clear, it is certainly possible for truly massive, previously private datasets to be publicly leaked or compromised. However, this scenario does not reflect the majority of Telegram channels and dark web threat actors claiming to offer such data.

Some might counter this by saying: “You’ve only analyzed obviously bad sources — there are good ones too.”

That is true — high-quality sources do exist, and Group-IB actively monitors them. But as we’ve stated throughout this report, the existence of better sources does not change the nature of Combolists and ULP files as fundamentally secondary and often unreliable forms of data. They must always be approached with a healthy degree of skepticism.

Given these challenges, Group-IB analysts urge the cybersecurity community to go beyond simply aggregating and re-reporting data from dubious Combolists and ULP files. Instead, efforts should be focused on identifying the original sources of compromise — the actual breach points — rather than relying solely on the convenience, speed, or trustworthiness of those who repackage and redistribute information in seemingly polished formats.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What should I do if I find my credentials in a combolist?

Change your passwords immediately, especially if you reused them across multiple accounts. Enable two-factor authentication wherever possible.

2. Are combolists illegal to download or view?

Accessing combolists can fall into a legal gray area, depending on your intent and jurisdiction. Sharing, selling, or using them for malicious purposes is typically illegal and unethical.

3. Can antivirus software detect stealer malware before it creates a log?

Sometimes, but not always. Modern stealers are designed to avoid detection. Keeping software updated and avoiding shady downloads is your best prevention.

4. Why do threat actors keep creating new combolists with the same old data?

It’s about marketing. Renaming old data makes it look “fresh” to unsuspecting buyers, helping sellers drive downloads, reputation, or profits.