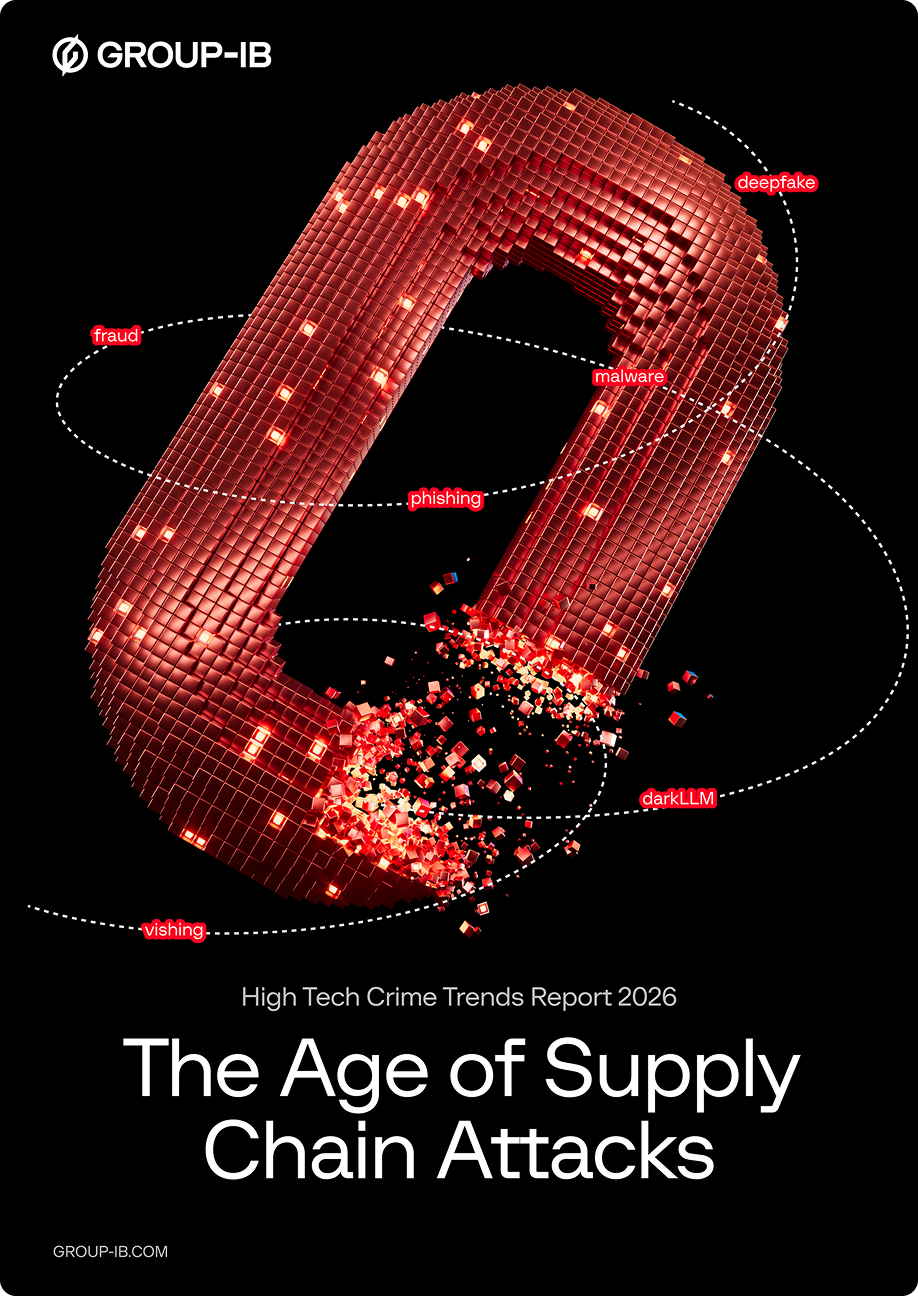

Introduction: Exploring Another LATAM Land; Uncovering Another Cyber Scheme

Cybercriminals had nefarious tricks up their sleeves in Brazil. After uncovering them, we sailed northwest and reached the digital harbors of Colombia. Here, another scheme awaited us—a crafty operation targeting car insurance. This scam relies on fake websites to deceive users, leveraging publicly available vehicle registration numbers to add a layer of credibility.

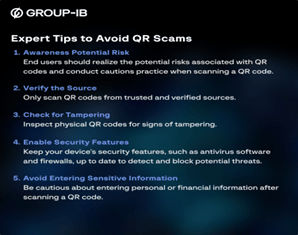

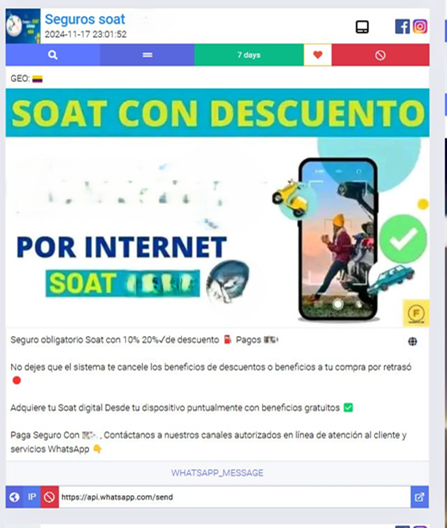

Since the beginning of 2024, we have identified over 100 fraudulent websites linked to this scheme, each crafted with guile, meticulousness, and precision to be a digital double of legitimate services and exploit unsuspecting victims. These sites represent a widespread and systematic effort to target individuals seeking damage-precautionary and mandatory vehicle insurance. The journey customers may take for a sense of security becomes the criminal means of entrapment, which starts with ads on social media platforms like Facebook. The messaging is built around enticing users with promises of substantial discounts, sometimes up to 20%. These ads are polished, often featuring trusted logos and links to WhatsApp for “customer assistance.”

Image 1: Vehicle insurance with discounts is advertised on a social network

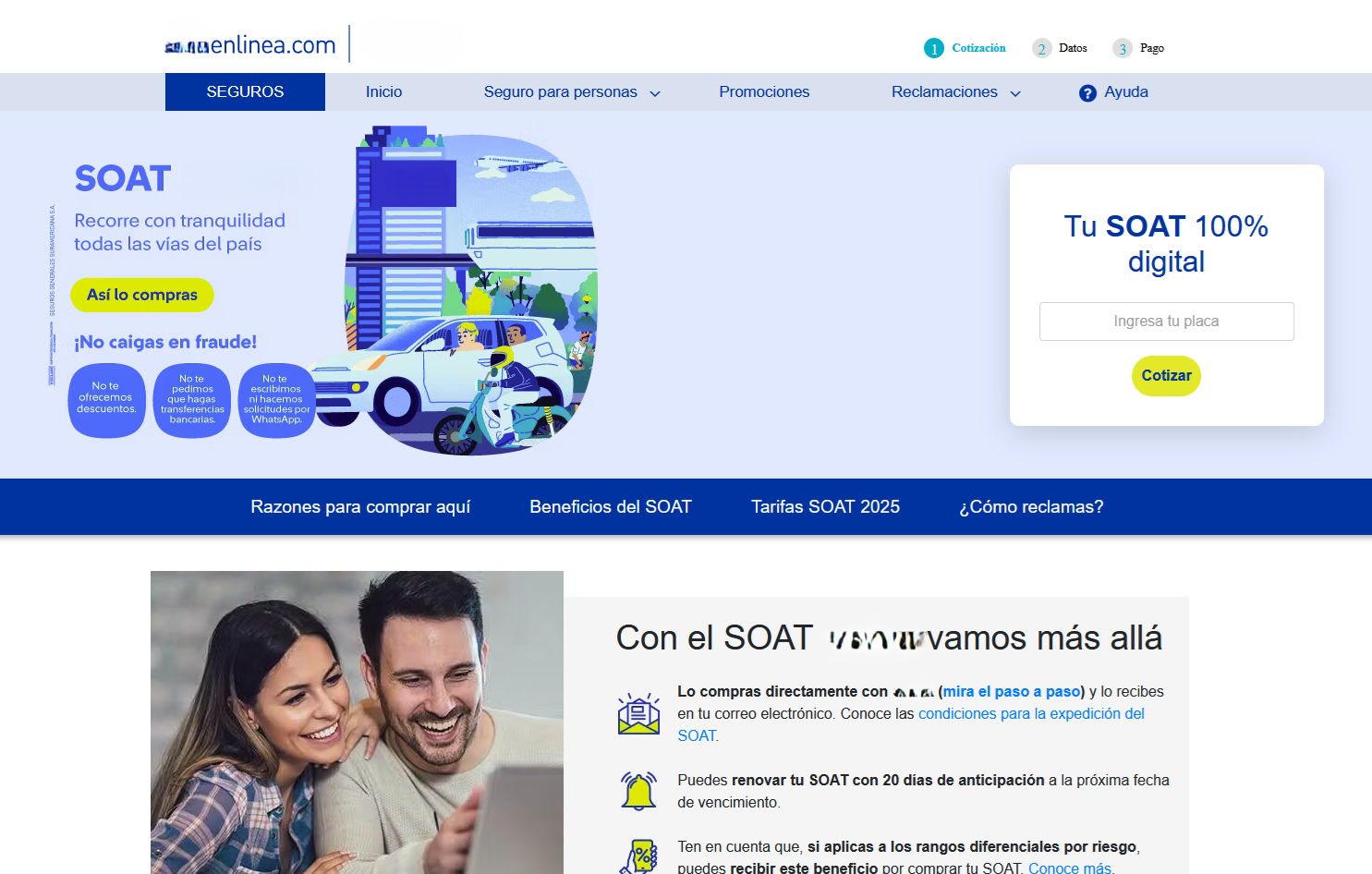

Once the victim engages via WhatsApp, the scammers redirect them to a fake website posing as a legitimate car insurance provider. The site nudges users to enter their vehicle registration number, initiating a process that feels remarkably authentic. The scam’s effectiveness lies in validating the vehicle’s insurance status. The site denies the purchase if the insurance is still active, reinforcing its credibility as a legitimate service. However, if the insurance has expired, the site displays accurate vehicle details, making it almost impossible for users to suspect foul play.

Trust Trap: Sharing the right information to build premise for the wrongdoing

When users interacted with the site, several information cues were presented based on their vehicle status—details that cybercriminals had carefully extracted from public databases and government sites. The intent was to appear legitimate, exploit users’ trust, and convince them to make payments to “activate” their insurance. Our experts mapped out every piece of information the attackers requested.

Seguro Obligatorio de Accidentes de Tránsito (SOAT) — A Colombian Mandate:

In Colombia, vehicle traffic accident insurance, called SOAT in Spanish, is mandatory. This insurance must be renewed every year starting on January 1, and for antique and classic vehicles, it must be renewed every three months. Scam websites exploit this legal requirement by asking users to enter their vehicle license plate number.

The scam site initiates a seemingly legitimate process that validates the vehicle’s insurance status — If the SOAT is active, the site denies renewal, making it seem authentic. If it’s expired, the site displays real vehicle details (e.g., type of vehicle, motor number), creating trust.

Image 2: This page ask only for the vehicle license plate number

Use of Publicly Available Information to Buy-In Confidence

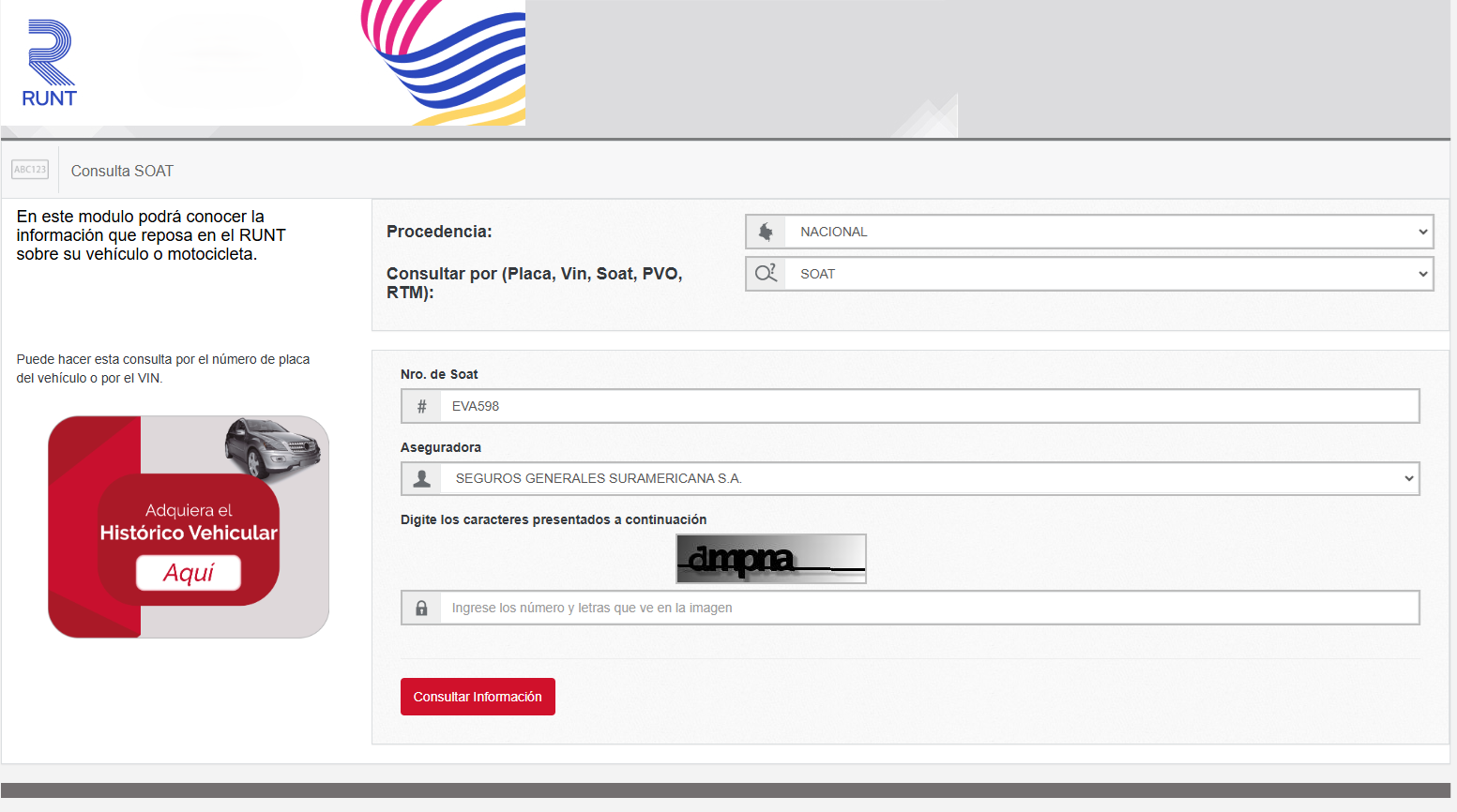

The scam leverages publicly accessible data from the Colombian government’s vehicle information portal: https://www.runt.gov.co/consultaCiudadana/#/consultaVehiculo, although access is restricted to Colombian IP addresses.

Image 3: Checking information about a vehicle with the insurance number (SOAT)

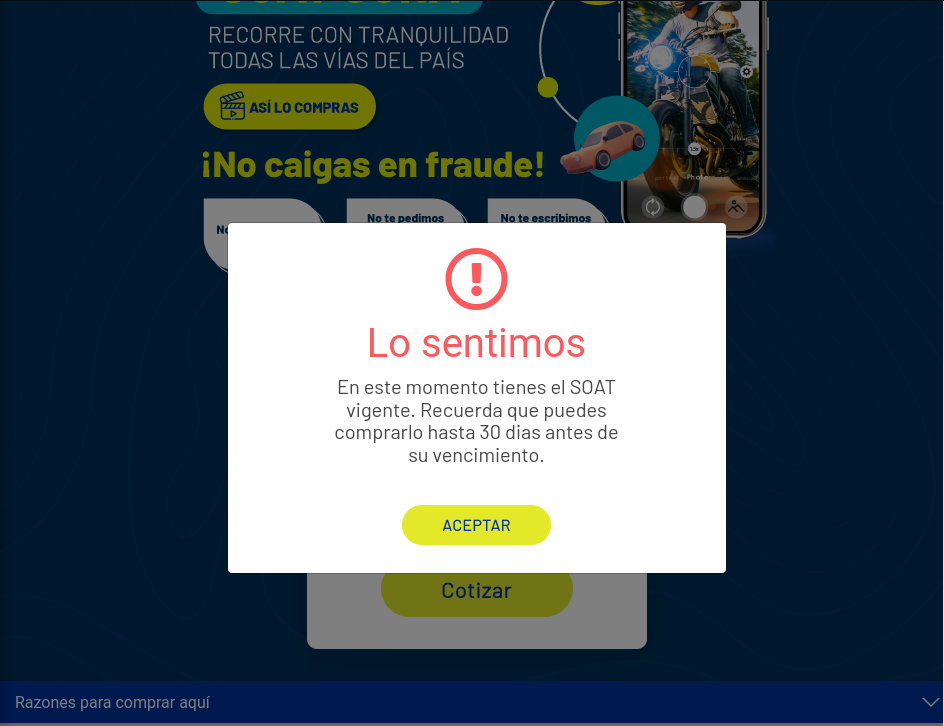

When the site identifies that the insurance is still valid, it presents a message to the user indicating that they cannot continue because the insurance (SOAT) is active and has not expired yet . It reminds the user that they can purchase new insurance only 30 days before expiration.

Image 4: After verification of a license plate number, the site indicates that the insurance (SOAT)

is active

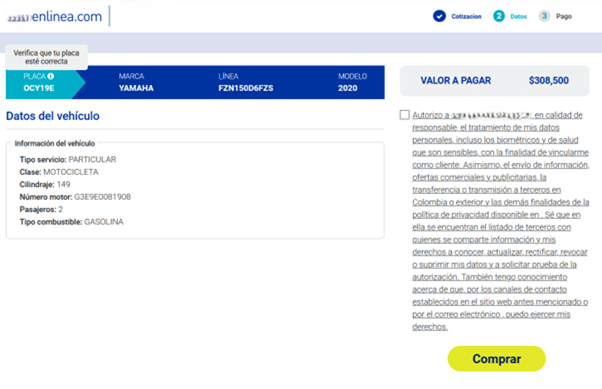

When the page identifies that the insurance has expired, it brings all the car information

and value, which makes the user trust the site by presenting real information.

Image 5: The site presents collected information about the vehicle, including the type of service,

the type of vehicle, and the motor number, among other things.

In some other instances of this same type of site, they also requested the personal information of the user, including:

- Full name

- Identification number

- Home address

- email address

- Name of the bank

- Bank account number

When victims click to pay for this product (the yellow “comprar” button), they are redirected to another fraudulent site using the PSE brand trademark. Here, they are asked to enter their bank details for money transfers.

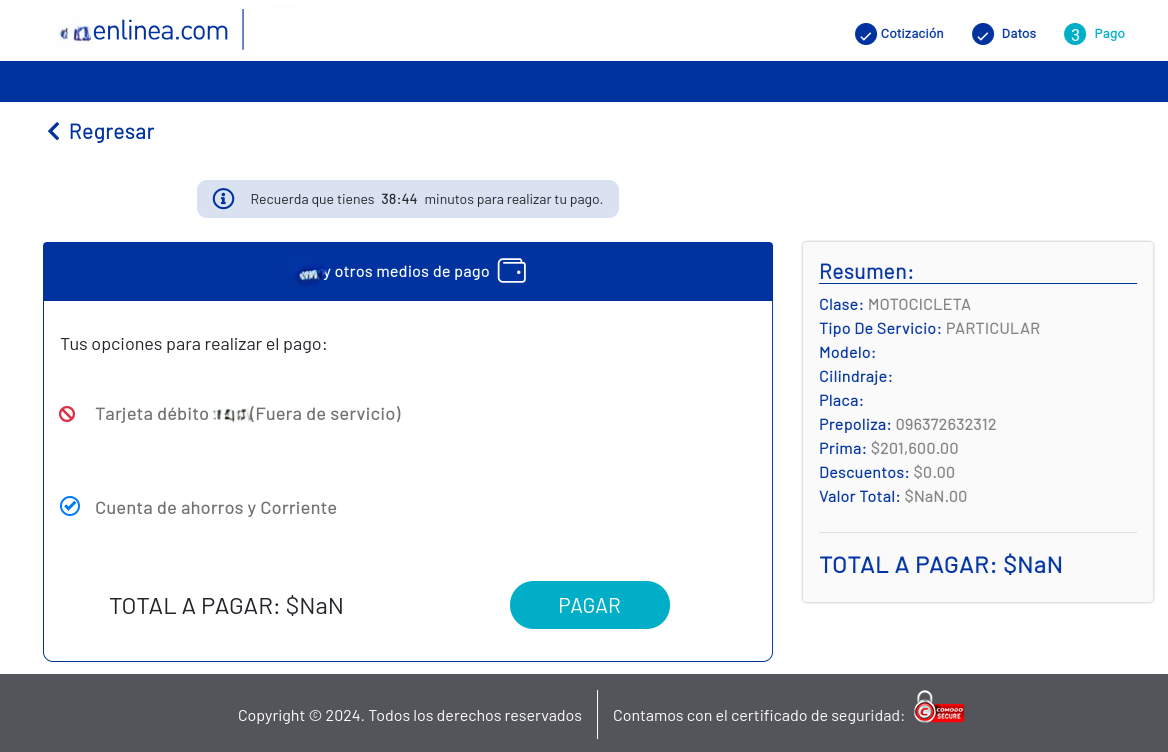

Image 6: The payment step shows the vehicle information and the payment methods for the insurance

Secondary Site For Choosing Payment Methods

Thanks to smartly crafted nudges, the victims have no doubts about the process’s credibility. They purchase the insurance, which leads them to a secondary site: a scam payment gateway.

Here, the victims are asked to enter sensitive information, including their banking details, card numbers, or account information. The gateway, replicating the look and feel of a legitimate financial platform, reassures users that their data is secure.

Once the banking details are entered, victims are redirected to one final step that concludes the entire scam—a page designed to resemble a trusted payment system. This page asks them to enter their phone number and password to complete the transaction.

Scammers then gain access to the victim’s financial accounts. From there, they swiftly transfer funds to their own accounts, leaving victims dumbfounded.

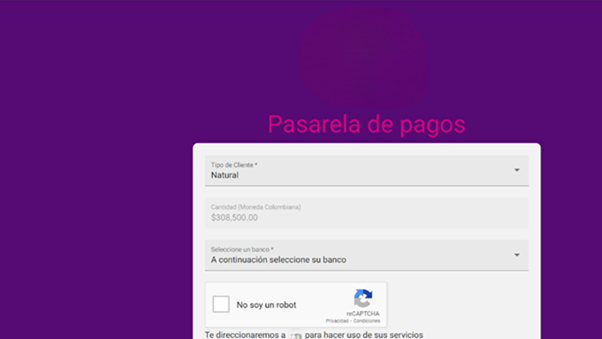

Here are the examples of the different secondary sites where the bank information is requested.

Image 7: Screen showcasing request for information about the type of client (Individual or

commerce) and bank name.

Image 8: Information requested in the above image. Full name, identification number, address, email, name of the bank, bank account number

Image 9: Screen showcasing request for bank name and email address information

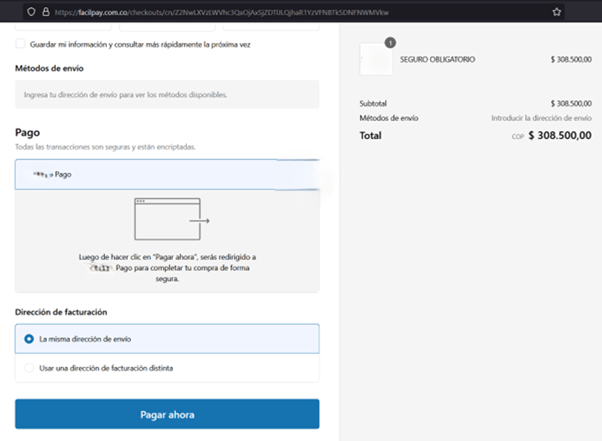

After all the information is filled out and the user clicks the next step to make a payment, they are redirected to a third site, which deceives them into making a transfer.

Final Destination

Here, the transaction is performed using a phishing page and a Colombian transaction system to make the money transfer.

Image 10: Screen showcasing the request for the cellphone number and password of the service for money transfer

The scam scheme demonstrates the sophisticated social engineering used by scammers in Colombia. Special measures are taken to “build trust” and improve the campaign’s effectiveness. Coupled with professional design and a multi-layered deception strategy, they build a trap that’s hard to escape.

This is a strong reminder for vehicle owners in Colombia to scrutinize online offers—even when they appear legitimate.

For cybercrime investigators, this means digging deeper into criminal strategies and disrupting their operations before they claim more victims.

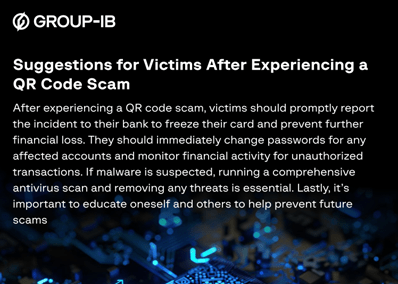

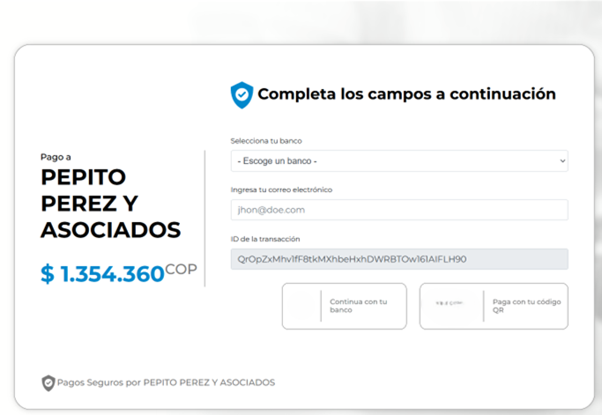

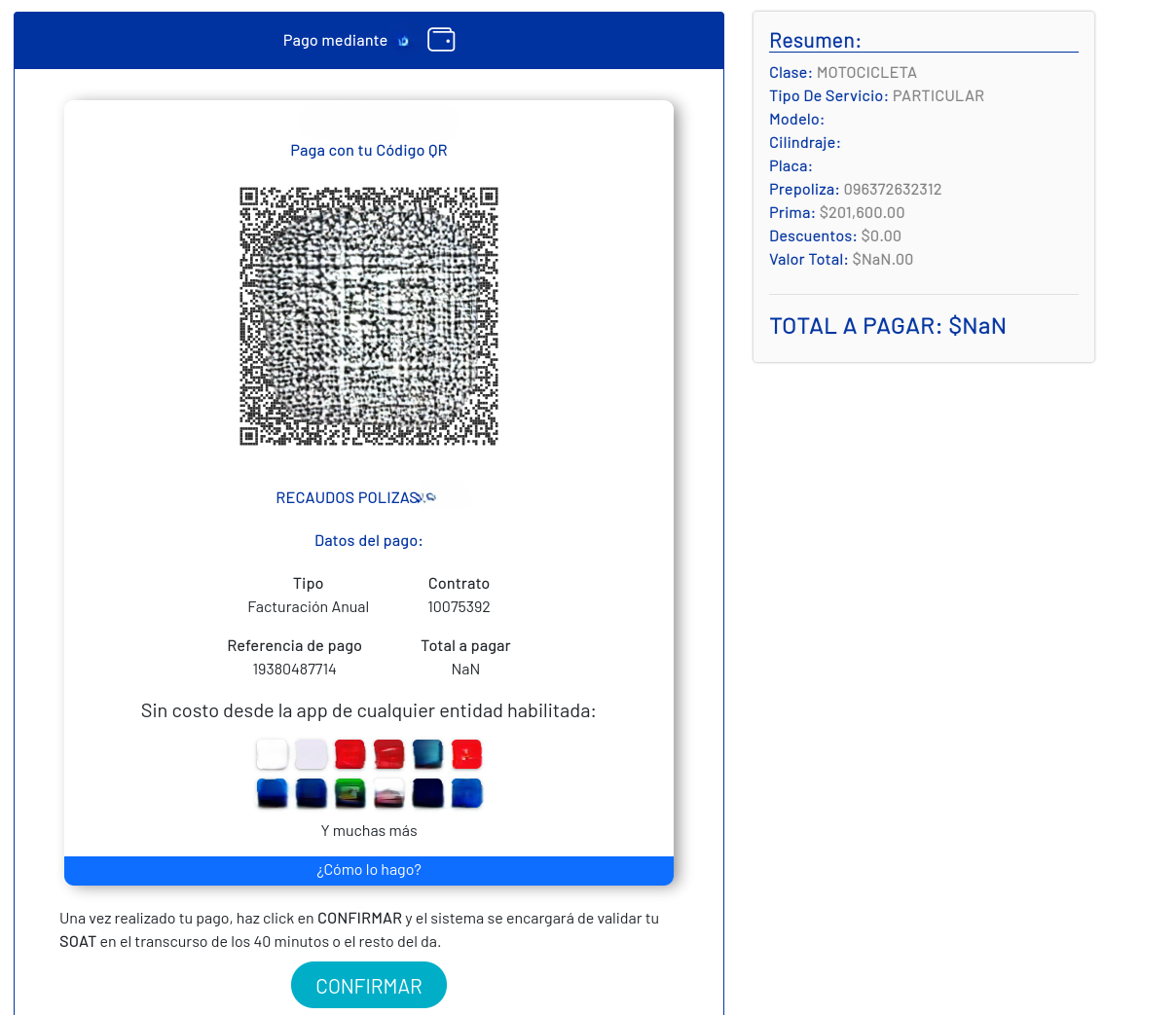

An alternate payment Trap: QR code scam

Another method to scam people chosen by cybercriminals is to make them scan a QR code on the same site without going to another page. In this step, the users are presented with a QR image that they must scan with an official bank or financial application.

The scammers send the victims all the necessary payment information so that they can transfer money from their personal accounts to their illicit accounts.

Image 11: The site indicates to scan a QR code with the official apps of banks or financial platforms to

transfer the amount of money

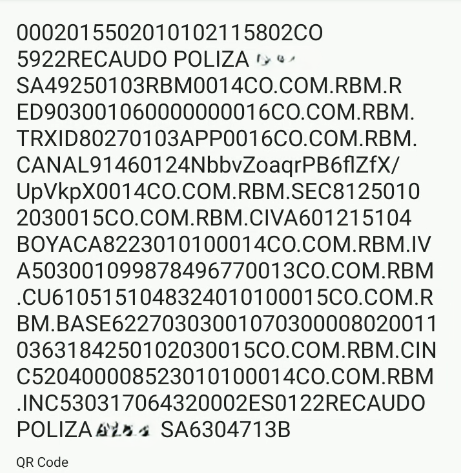

Image 12: Fake insurance transaction information for the QR code.

This QR code appears to be a payment request for a service provided by “Recaudo Poliza -BRAND NAME-,” likely related to an insurance policy payment. Here’s a summary of what it might represent:

- Merchant: -BRAND NAME- (a Colombian insurance/financial company).

- Location: Boyacá, Colombia (postal code 15104 aligns with this region).

- Purpose: Collection of a policy payment or related fee.

- Transaction Details: Includes identifiers like a transaction ID, secure token, and possibly an amount (though the exact amount isn’t explicitly clear from the text alone—it may require a specific app or system to interpret the numeric fields like 09987849677 or 170).

- Payment Network: References to COM.RBM suggest the involvement of Redeban Multicolor (RBM), a major Colombian payment processor.

No visible “account number” is labeled as such in this QR code. The closest we come to it are:

- NbbvZoaqrPB6flZfX/UpVkpX (Tag 91): This secure token might encode an account identifier, but it’s not human-readable without additional context or a decoding system.

- 0363184 (Tag 62): This could be an invoice or reference number tied to an account in the merchant system, but it’s not a bank account number.

In Colombian QR payment systems (like those processed by Redeban), the “account” is often implicitly tied to the merchant and processed through the payment network (RBM).

For security reasons, the actual bank account details are typically handled server-side and are not exposed in the QR code.

Without scanning the QR code or having a specific decoder for this format (e.g., a Colombian payment app), we can’t confirm the exact transaction amount or fully validate the checksum (713B). However, the structure strongly aligns with QR payment standards used in Colombia.

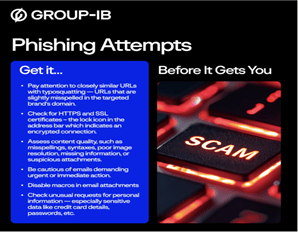

Vehicle owners looking to get insured: Follow these steps to avoid getting trapped

These scams are a striking reminder of the need for constant vigilance and early protection. Here are some steps that can help safeguard against such threats:

Verify the Source: If an offer appears too good to be true, it likely is. Before providing personal information, especially sensitive data like CPF, always confirm the site’s legitimacy or communication. Even leverage an IP lookup tool to confirm if the site is authentic from https://scamalytics.com/ip

For phishing and QR scams:

Education and Awareness: Knowledge is essential. Ensure that you are well-informed about prevalent scams in the region and can identify fake websites and phishing attempts.

Report Fraud Immediately: If you encounter a fake site or phishing attempt, report it to the relevant authorities to help reduce its spread and protect others from becoming victims.

For Businesses

Leverage technologies to detect fraudulent domains and phishing sites—prevent them from ever reaching your users.

For Brand Protection, Impersonation Attempts, Scam Intelligence, and More — Choose Digital Risk Protection

Protecting your digital identity from multifaceted attacks should be a top priority for businesses. Brand impersonation, scams, data breaches, leaks, and illegal mentions continue to surface across social media, the dark web, underground forums, and other online platforms, posing serious risks.

Group-IB’s Digital Risk Protection (DRP) helps you monitor, detect, and defend against these threats before they impact your organization.

As criminals continually refine their tactics, staying ahead is no longer optional—it’s necessary. Understanding local nuances and the digital landscape is crucial to defending against growing threats.

For Fraud Identification and Mitigation — Choose Fraud Protection

Group-IB Fraud Protection, powered by an in-built intelligence platform, integrates Cyber Threat Intelligence and adversary Techniques, Tactics, and Procedures (TTPs) to provide a clear view of fraud schemes in your region, mapped against the MITRE ATT&CK framework for a multi-layered defense approach.

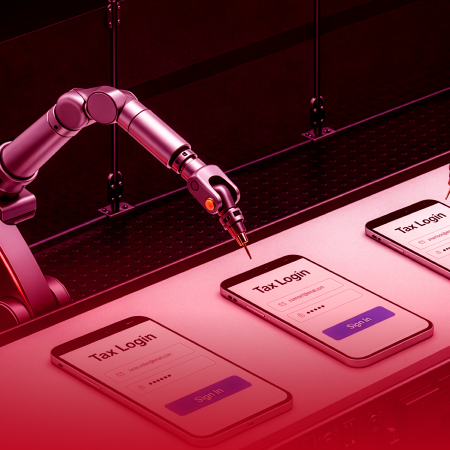

Phishing Detection: Fraud Protection flags suspicious QR-linked payment pages by analyzing submission sites and referring links. It works with Threat Intelligence to block fake domains in real-time.

Malware and Behavioural Threat Detection: If malware is installed via a scanned QR code, Fraud Protection detects it upon app launch. Our AI system analyzes user behavior—typing patterns, app usage, and geolocation—to spot potential threats.

More than just a detection tool, our solution identifies early fraud indicators. It stops threats before they escalate, making it one of the most comprehensive anti-fraud solutions in the market.*