Introduction

What is your understanding of incident response? Is it the process of limiting or preventing damage to a company under attack? Is it the steps taken in the aftermath to prevent repeat infection? Or, is incident response the process of negotiating with threat actors? Well, it’s all the above, and more. That’s why Group-IB is launching a new blog series called The Untold Story of Incident Response, detailing some of the most notable cases faced by Group-IB’s Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) team during their more than 70,000 hours of diligent work helping organizations respond to cyber attacks.

In this edition of The Untold Story of Incident Response, we recount a triumph by Group-IB’s incident responders that saw them jump into action and leverage the company’s proprietary Managed XDR solution to thwart an ongoing attack and ensure that an organization avoided the worst impacts of a successful intrusion. Our rapid response meant that we were able to stop a ransomware gang in its tracks before they were able to encrypt the files of a company whose systems they gained access to – a truly rare phenomenon.

The genesis of Group-IB lies in the domains of digital forensics, incident response to stop ongoing attacks in their tracks, and high-tech cybercrime investigations to uncover the identities of cybercriminals, and the company now has more than two decades of battle-earned experience responding to attacks of all severity. In particular, Group-IB’s DFIR team specializes in solving the most complex of cases, whether that be an attack involving one or more threat actors, attacks in which 90% of the victim’s infrastructure is paralyzed, as well as cases in which a victim organization entered into negotiations with the attackers that turned sour. In short, Group-IB’s incident responders are there to make miracles happen when all seems lost.

As a result, an extensive repository of attack-related data, techniques, and malevolent actors was amassed. This treasure trove led to the creation of the Group-IB Threat Intelligence department. Foremost among their mandates was the vigilant monitoring of threat actors. It is with considerable pride that we reflect upon the pivotal role played by our adept Threat Intelligence team in the unfolding of this narrative.

Alarm bells ringing

Last Christmas, a significant breakthrough occurred when Group-IB Threat Intelligence successfully located a command-and-control (C&C) server associated with a backdoor named SystemBC, which has previously been exploited to deploy ransomware. This discovery allowed us to begin monitoring several new victims, identified solely by their computer names and IP addresses. Armed with this information, Group-IB experts conducted targeted research that led to the identification of a European company as the latest victim of the SystemBC backdoor late last year. Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the Group-IB Threat Intelligence team immediately reached out to members of the European country’s national authorities to alert them to the ongoing cyber attack.

Remarkably, an official from the country’s national authorities was able to almost immediately visit the affected company physically. They simply knocked on the door and informed the present employees of the recent breach and the imminent threat of data encryption. This step kicked off the incident response process.

Group-IB incident responders, who commenced their efforts on December 24, had their task made simpler by having Threat Intelligence data that informed them of the date of attack, the targeted server, and the type of malware that was in the infected system. They began by examining the noteworthy events that preceded the breach. On December 21st at 18:00 CET, the event journal of the infected system was cleared. At 20:20 CET, a PowerShell script was identified in the event journal, purposed for dumping “lsass.exe” in order to potentially extract credentials with tools like Mimikatz. Upon further scrutiny, it was revealed thatnetscan.exe, a recognizable SoftPerfect Network Scanner utility, was executed on December 21st at 19:57 CET. This sequence of events is typical of the early stages of intrusion.

Delving deeper into the SoftPerfect net scanner, it was discovered that the tool displayed an interface in Russian – a strange occurrence given that the target company was based in Belgium and a sign of malicious activity. Furthermore, the scan configuration contained a list of company user accounts and associated passwords. This raised two pivotal questions: what was the origin of the acquired credentials and was the early deletion of the system logs around 18:00 an attempt by the cybercriminals to cover their tracks?

Group-IB’s incident responders conducted a careful analysis, and this coupled with their data recovery efforts, provided insights that could potentially answer these two questions. Firstly, a Mimikatz output file, dated December 20th, was uncovered in the Downloads folder on the infected host, which indicates that the initial intrusion took place slightly earlier. Secondly, the decision to clear the event journal was an evident attempt by the initial intruder to obscure their tracks.

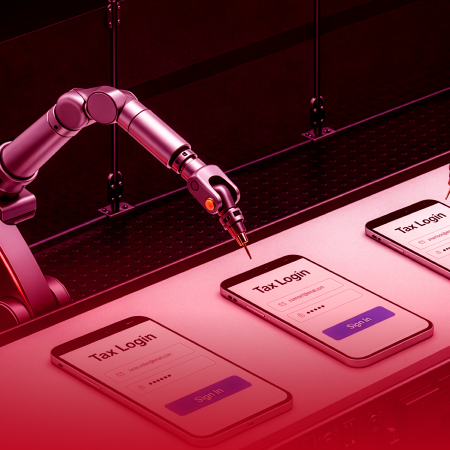

Upon closer inspection of the initial intruder’s actions, several more curious instances were identified. At around midnight CET on December 17th (a Friday), a user named Administrator executed a command line on a server with an open Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) port. Subsequent events included the installation of AnyDesk – a remote access tool – by the same user on December 19th, followed by the upload of various hacking tools.

| Name | Description |

| Advanced_Port_Scanner_2.5.3869.exe | Network scanner |

| backup.bat | Bash script to delete backups |

| PsExec.exe and PsExec64.exe | A legitimate utility enabling the threat actors to execute files on remote hosts |

| tni-setup430_4113.exe | Multipurpose tool for network inventory (scanning) |

| WebBrowserPassView.exe | Web Browser Password Viewer |

| netpass (1).exe | Recovering locally stored passwords for network computers |

Figure 1. Tools uploaded by the first threat actor on December 19th.

This culminated in the creation of a new folder named C:/NL/ on December 20th, housing a range of hacking tools like Mimikatz.

A little later, Group-IB incident responders discovered that, in fact, a second threat actor had intruded into the victim organization’s network. Their actions bore similarities to the first intruder, although there were some subtle differences. A network scan initiated by the second actor mirrored that of the initial intruder. The crux of differentiation rested in the minute details. For example, they may have used the same tools and same host, but with different versions or filenames. Additionally, they can use files with the same names, but hosted in different folders. These disparities strongly indicated distinct groups at play.

| 1st threat actor | 2nd threat actor |

| Advanced_Port_Scanner_2.5.3869.exe | AdvancedSERG_Port_Scanner_2.5.3581exe |

| WebBrowserPassView.exe | WebBrowserPassView.exe |

| netpass (1).exe | netpass.exe |

| Used “C:\Users\Administrator\Downloads\” and “C:\NL\” folders | Used only “C:\Users\Administrator\Music\” folder |

Figure 2. Differences between the first and second threat actors in their approach (filenames, folders).

You may ask “Why do we see two threat actors – one after another?” The answer may be simple. The initial intruder is known as a partner or initial access broker. They conduct the opening gambit. They complete the initial compromise, steal credentials, and conduct network reconnaissance. After this, the partner sells access to the infected network to a ransomware group (which explains why the Netscanner configuration contained a list of company usernames and passwords).

As the incident unfolded, the second threat actor introduced additional tools to their arsenal on December 24, suggesting an escalation in the attack that was likely to result in an attempt by the cybercriminals to leverage ransomware in order to encrypt the victim company’s files. This is a common pattern seen among ransomware gangs, who launch attacks on weekends or national holidays, when fewer employees are at their computers.

On Christmas Eve, the cybercriminals added tools named dfControl and PCHunter to the Music folder of the infected system. dfControl was designed to disable Windows Defender, while PCHunter functioned as an equivalent to Process Hacker – a process visualization tool. This strategic shift highlighted the actor’s efforts to overcome the resistance posed by Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) systems.

The story culminates with the final confrontation. The second actor’s attempts were thwarted, as Group-IB’s Managed XDR blocked the execution of both Mimikatz and dfControl, which likely led to them realizing that their actions had been detected and countered.

We were left to try to imagine the faces and the cries of the threat actors.

- “What is blocking Mimikatz? Is it Windows Defender?!”

- “Nope, you’re mistaken!” a Group-IB incident responder chuckled

- “Let’s disable Windows Defender with dfControl!”

- “Nice try, but we’ve blocked dfControl as well”, our incident responders said.

- “What’s happening?! I need to check all the processes with PCHunter. Oh, it’s Group-IB Managed XDR! Release the Kraken!”

As a last resort, the threat actors launched Cobalt Strike. This played directly into Group-IB’s hands though, as this led to the rapid identification of the command-and-control server, which then enabled us to neutralize it. Additionally, this shed light on the threat group responsible for the attack, and also gave us information that can be shared with law enforcement at the client’s request.

The entire incident response operation spanned approximately six hours and concluded successfully with the affected organization not suffering any substantial damage, both financially and reputationally. Further investigation of the SystemBC backdoor carried out by Group-IB Threat Intelligence revealed more than 100 victims. We weren’t able to come to the assistance of everyone, but we came to the rescue and saved the day for multiple companies by reacting and removing the threat before the ransomware gang was able to encrypt the files.

This leaves us with the key lesson from our Yuletide story. Rapid incident response helps avoid major damage. The invincible synergy between robust Threat Intelligence solutions and effective Incident Response engagements serves as a shining example for others to follow, and this will continue to be at the heart of Group-IB’s future endeavors.

Recommendations

- Proactively leverage advanced tools such Threat Intelligence to ensure that you have full coverage of the threat landscape to protect against attacks before they happen.

- Employ Managed XDR tools to detect malicious activity in your network and end points and block the development of the attack before it causes major damage.

- If an event happens and your company does not have an in-house team of experienced incident response professionals, contact a third-party incident response provider immediately to ensure swift and effective action to mitigate the ongoing attack

- We recommend that organizations with non-mature incident response to opt for an Incident Response Retainer. This proactive step provides them with the assurance that they won’t have to face a crisis alone, when it occurs.